Shoot the Moon

| Shoot the Moon | |

|---|---|

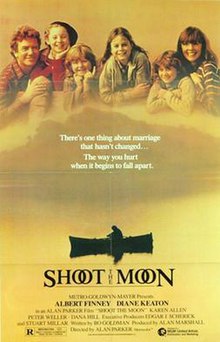

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Alan Parker |

| Written by | Bo Goldman |

| Produced by | Alan Marshall |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Michael Seresin |

| Edited by | Gerry Hambling |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | MGM/United Artists Distribution and Marketing |

Release date |

|

Running time | 123 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $12 million[2][3] or $14 million[4] |

| Box office | $9.2 million[5] or $2.5 million[4] |

Shoot the Moon is a 1982 American drama film directed by Alan Parker, and written by Bo Goldman. It stars Albert Finney, Diane Keaton, Karen Allen, Peter Weller, and Dana Hill. Set in Marin County, California, the film follows George (Finney) and Faith Dunlap (Keaton), whose deteriorating marriage, separation and love affairs devastate their four children. The title of the film alludes to an accounting rule known in English as "shooting the moon" in the scored card game hearts.

Goldman began writing the script in 1971, deriving inspiration from his encounters with dysfunctional couples. He spent several years trying to secure a major film studio to produce it before taking it to 20th Century Fox. Parker learned of the script as he was developing Fame (1980), and he later worked with Goldman to rewrite it. After an unsuccessful pre-production development at Fox, Parker moved the project to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, which provided a budget of $12 million. Principal photography lasted 62 days, in the period from January to April 1981, on location in Marin County.

Shoot the Moon premiered on February 19, 1982 to mostly positive reviews, but was deemed a box-office failure, having grossed only $9.2 million in North America. It later competed for the Palme d'Or at the 1982 Cannes Film Festival, and received two Golden Globe Award nominations for Best Actor – Drama (Finney) and Best Actress – Drama (Keaton).

Plot

In Marin County, California, writer George Dunlap and his wife Faith are an unhappy couple who live with their daughters Sherry, Jill, Marianne, and Molly in a farmhouse that George has refurbished. George is preparing to attend an awards banquet in his honor, when he makes a phone call to Sandy, a single mother with whom he has begun an affair. Sherry, the oldest of the four children, picks up the phone and listens in on the conversation.

After the children leave for school the next morning, Faith expresses her suspicions of the affair, prompting George to leave and move into his beach house. Sherry refuses to speak to George, while her sisters visit George on weekends. Jill, Marianne and Molly also meet Sandy, who harbors cynicism towards them and views them as a distraction in her sexual affair with George.

Faith falls into depression, but is elated when she begins a relationship with Frank Henderson, a contractor she has hired to build a tennis court on the grove of the farmhouse. One day, George visits the farmhouse, aggressively requesting to Faith that he be able to give Sherry her birthday present, a typewriter. George grows frustrated upon meeting Frank and seeing the construction work being done to the yard. George returns to the home later that night, again demanding that he be able to give Sherry her present. When Faith refuses to let him in, George breaks the door apart, pushes her out of the house, and blocks the entrance door with a chair. After Sherry refuses the gift, George spanks her repeatedly. The other children try to fight him off, but George does not relent until after Sherry threatens him with a pair of scissors. After Molly lets her back into the house through a side door, Faith comforts a sobbing Sherry, and George leaves ashamed.

George and Faith go to court to begin the first stage of their divorce proceedings, which involves joint custody of the children. After the court hearing, Faith tells George that her father has been hospitalized. At the hospital, they both downplay the disintegration of their marriage, but Faith's father senses that they are lying, and dies shortly thereafter.

After the funeral, George finds Faith having dinner at a restaurant and joins her. They have a heated, passionate exchange, arguing about their relationship before getting drunk. They go to a hotel room where Faith and the children are staying, and have sex. After Sherry enters Faith's bedroom and finds them lying in bed, Faith asks George to leave.

When the tennis court is completed, Faith and Frank throw an outdoor party at the farmhouse. Sherry scorns her mother for having sex with George and Frank before running away. She runs to George's beach house where she sees her father playing a game of hearts with Sandy and her son. George looks out the window and sees Sherry sitting on a pier. He goes to comfort her and as they reconcile, he gives Sherry the typewriter.

George returns Sherry to the farmhouse, where Faith invites him to visit the tennis court and meet Frank's friends. Under a seemingly friendly facade, George praises Frank for his work on the tennis court. He then goes into his car and crashes into the court repeatedly until it is demolished. Enraged, Frank pulls George out of the car and beats him relentlessly before walking away. As the children try to comfort their father, George reaches out for Faith to take his hand.

Cast

- Albert Finney as George Dunlap

- Diane Keaton as Faith Dunlap

- Karen Allen as Sandy

- Peter Weller as Frank Henderson

- Dana Hill as Sherry Dunlap

- Viveka Davis as Jill Dunlap

- Tracey Gold as Marianne Dunlap

- Tina Yothers as Molly Dunlap

- George Murdock as French DeVoe

- Leora Dana as Charlotte DeVoe

- Irving Metzman as Howard Katz

- Robert Costanzo as Leo Spinelli

- David Landsberg as Scott Gruber

- O-Lan Shepard as Countergirl

Production

Development

Shoot the Moon was Bo Goldman's first attempt at writing a screenplay and was originally developed under the title Switching. He began writing the script in 1971, influenced by his encounters with dysfunctional couples and how their disputes affected their children.[6] "When I started to write this screenplay years ago," he said, "I looked around me and all the marriages were collapsing, and the real victims of these marital wars were the children."[6]

For several years, Goldman tried to sell his script, without success.[6] Eventually, the script was picked up by 20th Century Fox after the commercial success of Star Wars (1977). Alan Ladd Jr., president of Fox, sent the script to Alan Parker, as the director was beginning pre-production on Fame (1980). After filming Fame, Parker met with Goldman, and the two worked together to rewrite the script.[2] Among the changes, they moved the story from New York City to Marin County, California,[2] and retitled the script Shoot the Moon, a metaphoric title that references the move of "shooting the moon" in the card game hearts.[7] After Ladd was fired from Fox in 1979, Parker discussed the project with Sherry Lansing, the studio's head of production, who balked at the film's proposed budget of $12 million.[2] Parker then discussed the project with David Begelman, head of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM), who agreed to green-light the film on the conditions that Parker stay on budget and secure Diane Keaton, a sought-after actress, in a leading role.[2]

Casting

In their search for actors, Parker and casting director Juliet Taylor held open casting calls in San Francisco, Los Angeles and New York City. For the role of George Dunlap, Parker first approached Jack Nicholson, who declined due to the script's subject matter. Parker then approached English film and stage actor Albert Finney, whom he had admired.[2] On portraying George, Finney said, "It required personal acting; I had to dig into myself. When you have to expose yourself and use your own vulnerability, you can get a little near the edge. Scenes where Diane Keaton and I really have to go at each other reminded me of times when my own behavior has been monstrous."[8]

Diane Keaton was cast as Faith Dunlap, George's wife. Parker had first discussed the role with her as the actress was preparing to film Reds (1981). He also discussed the role with Meryl Streep, who declined due to her pregnancy.[2] Keaton agreed to star in the film after the project was taken to MGM.[2] She described the film as "the war of a man and a woman who are breaking up and how the woman is crushed by this man going off and having an affair with someone else."[9]

Appearing as George and Faith's four children are Dana Hill as Sherry, Tracey Gold as Marianne, Viveka Davis as Jill and Tina Yothers as Molly. Of the four children, only Hill was an established actress, while the remaining three were making their feature film debuts.[2] Karen Allen secured the role of Sandy, George's mistress, after filming Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981).[2]

Filming

The film was made on a budget of $12 million.[3] Principal photography commenced on January 15, 1981.[2] During pre-production at 20th Century Fox, Parker, producer Alan Marshall and production designer Geoffrey Kirkland spent several months searching for houses to depict the Dunlap family home. They discovered the Roy Ranch House, an abandoned, 114-year-old clapboard ranch house in San Francisco.[10] The production dismantled the house into four pieces, which were then transported to the Nicasio Valley region of Marin County, California. The filmmakers spent six weeks restoring and decorating the house, as well as constructing a driveway, gardens and a tennis court.[2]

Scenes set in Sandy's beach house were filmed in Stinson Beach, California.[10] George and Faith's divorce proceeding was shot at the Napa County Courthouse Plaza in Napa, California. The filmmakers also filmed scenes at the Wolf House, Jack London's estate in Glen Ellen, California.[10] In San Francisco, the production shot scenes at the Fairmont Hotel in San Jose, California. Other filming locations included California Street, the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge, Sea Cliff and St. Joseph's Hospital.[10] Filming concluded on April 9, 1981 after 62 days.[2][11] Parker spent six months editing the film in London, England with 300,000 feet of film.[2]

Music

After working on the musical Fame, Parker had decided not to employ an original score for Shoot the Moon. Goldman selected the song "Don't Blame Me" from MGM's music library to be used in the film. The song is featured as a minimalist piano score that acts as a leitmotif. Parker stated, "I had it played on a piano with one finger—like a child would play, with innocent simplicity."[2][11] The film also features pre-recorded songs, including "Play with Fire" performed by the Rolling Stones and "Still the Same" performed by Bob Seger.[12] Parker explained that the songs were "selfishly chosen because they were contemporary songs that meant a lot to me personally."[2]

Release

Parker had hoped to release Shoot the Moon before the end of 1981 for awards consideration.[10] "It was ready for release in October of 1981," Goldman said in Peter Biskind's book Star: How Warren Beatty Seduced America (2010). "But Keaton was contractually prohibited from releasing another movie in the same calendar year as Reds. So we had to release Shoot the Moon in January 1982, right after New Year's, the worst possible time for a tough movie like this. The Alans—director Alan Parker and producer Alan Marshall—begged Beatty to release her from the obligation. His answer was, 'Nope, nope, nope.' It died as a result of the release date he had screwed us on."[13]

MGM gave Shoot the Moon a platform release, opening it in New York City, Toronto and Los Angeles on January 22, 1982,[10] before expanding to other cities in North America on February 19.[10] It was a box-office failure,[14] grossing $9,217,530 against a production budget of $12 million.[2][3][5]

In 1986, the distribution rights to the film were transferred to Turner Entertainment Co., which acquired MGM's pre-May 1986 library of feature films.[15] Currently, the rights are owned by Warner Bros., after its parent company Time Warner acquired Turner's library of MGM films in 1996.[16]

Home media

Shoot the Moon was released on DVD on November 6, 2007, by Warner Home Video. Special features include an audio commentary by Parker and Goldman, and the film's theatrical trailer.[17]

Reception

Critical response

Shoot the Moon received mostly positive reviews from critics.[11] On the Review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds a score of 85% based on 13 reviews, and an average rating of 7.72/10.[18]

Film critics Pauline Kael and David Denby, who had been dismissive of Parker's previous films, praised Shoot the Moon as his best directorial effort.[19][20] Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times appreciated the storytelling, stating, "Despite its flaws, despite its gaps, despite two key scenes that are dreadfully wrong, Shoot the Moon contains a raw emotional power of the sort we rarely see in domestic dramas."[21] In his review for The New York Times, Vincent Canby commended the acting, notably the performances of Finney, Keaton, Allen and Peter Weller, and compared the film to Kramer vs. Kramer (1979) and Ordinary People (1980), describing it as "a domestic comedy of sometimes terrifying implications, not about dolts but intelligent, thinking beings."[22] Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune called the film "an exceptionally strong family drama, with enough surprises to qualify as lifelike."[23]

A negative review carried by Variety termed the film "a grim drama of marital collapse which proves disturbing and irritating by turns."[24] Dan Callahan of Slant Magazine praised the performances, but criticized Parker's direction, writing, "Unfortunately, Shoot the Moon has some serious problems that get in the way of [Keaton and Finney's] unforgettable performances ... Though Parker's way of going for the jugular can be very effective in the big moments, he lets lots of small, deliberately banal domestic scenes just dribble away."[25]

Accolades

Shoot the Moon received several nominations, with particular recognition for Finney and Keaton's performances. In May 1982, the film competed for the Palme d'Or at the 1982 Cannes Film Festival.[26][27] It was one of two films directed by Parker to appear at the festival, the other being Pink Floyd – The Wall (1982), which was shown out of competition.[2] At the 40th Golden Globe Awards, the film received two nominations for Best Actor – Drama (Finney) and Best Actress – Drama (Keaton).[28] At the 36th British Academy Film Awards, Finney received a BAFTA Award nomination for Best Actor, but lost to Ben Kingsley, who won for Gandhi (1982).[29]

| List of awards and nominations | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Award | Category | Recipient(s) and nominee(s) | Result | Ref(s) | |

| 1982 Cannes Film Festival | Palme d'Or | Alan Parker | Nominated | [26] | |

| 40th Golden Globe Awards | Best Actor – Drama | Albert Finney | Nominated | [28] | |

| Best Actress – Drama | Diane Keaton | Nominated | [28] | ||

| 36th British Academy Film Awards | Best Actor in a Leading Role | Albert Finney | Nominated | [29] | |

| 18th National Society of Film Critics Awards | Best Actress | Diane Keaton | Nominated | [30] | |

| 48th New York Film Critics Circle Awards | Best Actress | Diane Keaton | Nominated | [31] | |

| 1983 Writers Guild of America Awards | Best Drama Written Directly for the Screen | Bo Goldman | Nominated | [32] | |

References

Notes

- ^ "Shoot the Moon". British Board of Film Classification. December 13, 1996. Archived from the original on September 6, 2017. Retrieved September 6, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Parker, Alan. "Shoot the Moon – Alan Parker – Director, Writer, Producer – Official Website". AlanParker.com. Archived from the original on September 5, 2017. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- ^ a b c Granger & Toumarkine 1988, p. 92.

- ^ a b Boyer, Peter J; Pollock, Dale (28 Mar 1982). "MGM-UA and the Big Debt". Los Angeles Times. p. 11.

- ^ a b "Shoot the Moon (1982)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on September 5, 2017. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- ^ a b c Hinson, Hal (July 11, 1982). "Cry of the Screenwriter". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on September 8, 2017. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- ^ Gonthier & O'Brien 2015, p. 83.

- ^ Farber, Stephen (July 26, 1981). "Finney comes back to film". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 5, 2017. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- ^ Mitchell 2001, p. 76.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Detail view of Movies Page". American Film Institute. Archived from the original on July 8, 2017. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- ^ a b c Gonthier & O'Brien 2015, p. 85.

- ^ Gonthier & O'Brien 2015, pp. 95, 101.

- ^ Biskind, Peter (2010). Star: How Warren Beatty Seduced America. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9780743246583.

- ^ Lindsey, Robert (April 14, 1982). "M-G-M U.A. shifts officials". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 8, 2017. Retrieved September 7, 2017.

- ^ Delugach, Al (June 7, 1986). "Turner Sells Fabled MGM but Keeps a Lion's Share". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 1, 2017. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- ^ Bloomberg Business News (September 27, 1996). "Warner Bros. to Run Most of Turner's Entertainment Unit". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on August 25, 2016. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Callahan, Dan (November 25, 2007). "Shoot the Moon DVD Review". Slant Magazine. Archived from the original on August 25, 2014. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- ^ "Shoot the Moon (1982)". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on November 28, 2017. Retrieved July 16, 2019.

- ^ Kael, Pauline (January 18, 1982). "The Current Cinema". The New Yorker.

- ^ Denby 1982, p. 66.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (January 1, 1982). "Shoot the Moon Movie Review & Film Summary (1982)". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on September 5, 2017. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (January 22, 1982). "Movie Review - - Finney and Miss Keaton in 'Shoot the Moon'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 5, 2017. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (February 19, 1982). "'Shoot the Moon' is a hearts game played for real". Chicago Tribune. p. 59. Archived from the original on September 5, 2017. Retrieved September 4, 2017.

- ^ Variety staff (December 31, 1981). "Shoot the Moon". Variety. Archived from the original on September 30, 2017. Retrieved September 30, 2017.

- ^ Callahan, Dan (November 25, 2007). "Shoot the Moon". Slant Magazine. Archived from the original on August 25, 2014. Retrieved September 30, 2017.

- ^ a b "Cannes 1982". cinema-francais.fr (in French). Archived from the original on June 13, 2017. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- ^ "Shoot the Moon - Festival de Cannes". Cannes Film Festival. Archived from the original on September 8, 2017. Retrieved September 7, 2017.

- ^ a b c "Winners & Nominees 1982 (Golden Globes)". Hollywood Foreign Press Association. Archived from the original on July 1, 2017. Retrieved September 5, 2017.

- ^ a b "Film in 1983". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Archived from the original on September 5, 2017. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- ^ "Tootsie acclaimed best film of '82; Hoffman best actor". The Phoenix. January 5, 1983. p. 32. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (December 21, 1982). "New York Critics Vote 'Gandhi' Best". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 5, 2017. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- ^ "Shoot the Moon (1982)". Mubi. Archived from the original on September 5, 2017. Retrieved September 4, 2017.

Bibliography

- Gonthier, David F. Jr.; O'Brien, Timothy L. (2015). "5. Shoot the Moon, 1982". The Films of Alan Parker, 1976–2003. United States: McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-9725-6.

- Granger, Rod; Toumarkine, Doris (November 1988). "The Unstoppables". Spy. United States: Sussex Publishers, LLC. pp. 88–94. ISSN 0890-1759.

- Mitchell, Deborah L. (2001). "5. 1982-1986: The Evolving Star Image". Diane Keaton: Artist and Icon. United States: McFarland & Company. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-7864-1082-8.

- Denby, David (January 25, 1982). "Going for Broke". New York. p. 66. ISSN 0028-7369.

External links

- Shoot the Moon at IMDb

- Shoot the Moon at the TCM Movie Database