Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge

Shepley, Rutan & Coolidge was a successful American architectural firm based in Boston. As the successor to the studio of Henry Hobson Richardson, they completed his unfinished work before developing their own practice, and had extensive commissions in monumental civic, religious and collegiate architecture. The original partnership was dissolved in 1914 and continued under the names Coolidge & Shattuck, Coolidge, Shepley, Bulfinch & Abbott and Shepley, Bulfinch, Richardson & Abbott. Since 2000 it has been active under the name Shepley Bulfinch.

History

The firm grew out of Henry Hobson Richardson's architectural practice. On the day of his death, Richardson left instructions that his practice should be continued by his three chief assistants: George Foster Shepley (November 7, 1860 – July 17, 1903), Charles Hercules Rutan (March 28, 1851 – December 17, 1914) and Charles Allerton Coolidge (November 30, 1858 – April 1, 1936), to whom in his declining health he had delegated greater and greater responsibility. Shepley was in charge of drafting, was Richardson's representative to clients and was engaged to Richardson's daughter, Julia Hayden. Rutan was the Richardson employee with the longest tenure and was the office's construction and engineering expert. Coolidge was Richardson's most favored designer. Before joining Richardson, both Shepley and Coolidge had worked for Ware & Van Brunt and had been educated at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Later, Coolidge married Shepley's sister, Julia.[1]

Following Richardson's instructions, and with the legal and financial backing of his friends and clients Edward W. Hooper and Frederick Lothrop Ames, they organized the firm of Shepley, Rutan & Coolidge in June in Richardson's Brookline studio. At first they were primarily engaged on the completion of Richardson's many unfinished works, including the Allegheny County Courthouse in Pittsburgh and the John J. Glessner House in Chicago.[1] By 1887 they had relocated from suburban Brookline to downtown Boston and were soliciting new work.[2] The three partners quickly settled into their new roles: Shepley and Coolidge as designers and Rutan as superintendent and office manager. Coolidge also emerged as the firm's promoter and rainmaker and quickly began to win major projects for the firm.[1]

By the time of Richardson's death, the Richardsonian Romanesque style with which he is associated had become widely imitated and was seen as old-fashioned by the most progressive American architects. Richardson himself was moving away from explicitly Romanesque detail, as at the New London Union Station (1887). Shepley and Coolidge initially continued as Richardsonian imitators. Later historians such as Henry-Russell Hitchcock have found their Richardsonian work to be of a higher quality than that of other imitators, though in their hands, without Richardson's imagination, it became stale and formulaic. Their Richardsonian works included the Ames Building (1889) in Boston, the Shadyside Presbyterian Church (1890) in Pittsburgh and the new campus of Stanford University (1891) near San Francisco.[3][1]

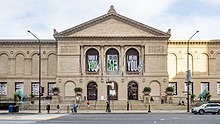

After a few years Shepley and Coolidge embraced the Neoclassical and other contemporary revival styles, following the lead of McKim, Mead & White, who after Richardson's death had taken his position as the leading American architects.[3] Their embrace of Neoclassicism first appeared in their unexecuted proposal for the Rhode Island State House (1891), a competition they lost to McKim.[4][1] Their first built Neoclassical works included the Art Institute of Chicago (1893) and the Chicago Cultural Center (1897). During this time they also became known for their Colonial Revival work, especially that at Harvard University. Their first Harvard building was Conant Hall (1894) and would hold a near monopoly on design work at Harvard during the presidency of A. Lawrence Lowell.[5] They were very successful in Chicago, where competing local architects began to jealously refer to them as "Simply Rotten & Foolish."[1] In 1892 Coolidge consolidated all of the firm's field offices into a Chicago branch office, with himself as resident partner until 1900.[6] If this move was in part an attempt to allay the Chicagoans' concern that they were architectural carpetbaggers, it was likely unsuccessful as additional important work, including the master plan and buildings of the University of Chicago, went into their office.[1] In 1893 a second branch office was established in St. Louis, Shepley's hometown, under the management of John Lawrence Mauran. In 1900, as Coolidge returned to Boston, the firm chose to withdraw from St. Louis, and Mauran and two associates bought out the local business to form the firm of Mauran, Russell & Garden.[7]

Shepley died in 1903 and Rutan became disabled in 1912, leaving Coolidge as the only active partner. Coolidge dissolved the partnership effective December 1, 1914, followed shortly by Rutan's death.[8] By this time, Coolidge had found that the firm's two offices acted largely independently, and in 1915 he organized new partnerships to operate both: Coolidge & Shattuck with George C. Shattuck (November 22, 1863 – September 3, 1923)[9] in Boston and Coolidge & Hodgdon with Charles Hodgdon (August 19, 1866 – November 21, 1953)[10] in Chicago. Though they were both directed by Coolidge, the two firms operated independently of one another.[11][12] In 1923, Shattuck died, and in 1924 Coolidge formed a new Boston partnership with Henry R. Shepley (May 1, 1887 – November 24, 1962),[13] Francis V. Bulfinch (June 3, 1879 – September 14, 1963)[14] and Lewis B. Abbott (June 27, 1878 – June 28, 1965),[15] known as Coolidge, Shepley, Bulfinch & Abbott. Shepley was the son of his former partner and his own nephew, and Bulfinch was the great-grandson of Charles Bulfinch.[16] In 1930, Coolidge retired from the Chicago partnership, which was thereafter known as Charles Hodgdon & Son.[17]

Coolidge was active as the senior partner of the Boston firm until his death in 1936, leaving the younger Shepley as senior partner. The name of the firm was not changed until 1952, when, with the addition of Joseph P. Richardson (April 9, 1913 – September 14, 1979),[18] it was renamed Shepley, Bulfinch, Richardson & Abbott. Richardson was, like Shepley, a grandson of H. H. Richardson. Other principals were added to the partnership over the next twenty years: in 1960 by James Ford Clapp Jr. (November 18, 1908 – January 22, 1998),[19] son of the former partner of Clarence H. Blackall, in 1961 by Sherman Morss (February 22, 1912 – February 29, 1996),[20] in 1963 by Jean Paul Carlhian (November 7, 1919 – October 18, 2012)[21] and Hugh Shepley (March 17, 1928 – September 4, 2017),[22] son of Henry R. Shepley, and in 1969 by Otis B. Robinson (April 25, 1916 – April 20, 1999).[23]

In 1972 the firm was incorporated and the partnership was dissolved. For several years, control remained in the hands of Richardson as the head of the internal Executive Committee. Corporate officers, including president, were elected annually and had limited power. This system ended in 1978, when Richardson retired and George R. Mathey (June 4, 1929 – July 9, 2020)[24] was elected the first long-term president. Mathey was a great-grandson of John J. Glessner, for whom H. H. Richardson had designed the John J. Glessner House. At this time the firm passed out of the control of the extended Richardson-Shepley-Coolidge family, which had led it since H. H. Richardson established himself independently in Brookline in 1878.[25]

The firm was recipient of many design awards from the American Institute of Architects (AIA) and other bodies, including the AIA Architecture Firm Award in 1973. In 1961 Shepley was made an officer of the Order of Orange-Nassau by Juliana, Queen of the Netherlands, in recognition of his design for the Netherlands American Cemetery in Margraten.[26] Over its long history the firm completed works in every major contemporary style. They made the difficult transition from traditionalism to modernism by melding Bauhaus functionalism with Beaux-Arts planning principles. This owed much to Carlhian, a French-born, Beaux-Arts-trained architect who had joined the firm in 1950. In 1999, historian Vincent Scully wrote that their work "[embodied] their own history of American architecture over more than a hundred years."[27] Since 2000 the firm has been known as Shepley Bulfinch.

Employees

Richardson's studio was known as a training ground for young architects, many of whom would become notable in their own right. This continued under the leadership of Shepley and Coolidge. Their employees included:

- John Scudder Adkins

- David Robertson Brown

- Herbert C. Burdett

- James Edwin Ruthven Carpenter Jr.

- Robert T. Coles

- Frank Irving Cooper

- John Robert Dillon

- Edward T. P. Graham[28]

- Alfred Hoyt Granger

- Henry Mather Greene

- Edwin Hawley Hewitt

- John Galen Howard[29]

- Myron Hunt

- Paul V. Hyland

- Arthur S. Keene[30]

- Samuel Abraham Marx

- Victor Andre Matteson

- John Lawrence Mauran

- Edward Maxwell

- Louis Christian Mullgardt

- Charles Nagel

- Joseph Ladd Neal

- Eliot Noyes[31]

- William G. Perry

- Roy Place

- Ernest John Russell

- Frederick A. Russell

- Frank E. Rutan

- Francis Sargent

- Edward Durell Stone[32]

- James Sweeney

- Hermann V. von Holst

Work

Boston & Albany Railroad stations

Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge also designed 23 stations for the Boston & Albany Railroad (1886 through 1894):[36]

- Newton Highlands station, Newton, Massachusetts (still standing)

- Union Station, Chatham, New York (still standing)

- Brighton station, Brighton, Massachusetts (still standing)

- Newton Lower Falls station, Wellesley, Massachusetts

- Ashland station, Ashland, Massachusetts (still standing)

- Reservoir station, Brookline, Massachusetts

- Dalton station, Dalton, Massachusetts (still standing)

- Springfield Union Station, Springfield, Massachusetts

- Wellesley Square station, Wellesley, Massachusetts

- Newton Centre station, Newton, Massachusetts (still standing)

- Huntington station, Huntington, Massachusetts

- Warren station, Warren, Massachusetts (still standing)

- Charlton station, Charlton, Massachusetts

- Brookline Hills station, Brookline, Massachusetts

- Hinsdale station, Hinsdale, Massachusetts

- Canaan station, Canaan, New York

- Millbury station, Millbury, Massachusetts

- Riverside station, Auburndale, Massachusetts

- Longwood station, Brookline, Massachusetts

- East Brookfield station, East Brookfield, Massachusetts

- Wellesley Farms station, Wellesley, Massachusetts (still standing)

- Saxonville station, Framingham, Massachusetts

- East Chatham station, Chatham, New York

Sources

- online biography at University of Nebraska

- Lyndon, Donlyn. (1982) The City Observed: Boston, A Guide to the Architecture of the Hub. Vintage Books

- Pridmore, Jay, and Kiar, Peter, The University of Chicago: an architectural tour

- *Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge at archINFORM

- Ochsner, Jeffrey Karl Ochsner, H.H. Richardson, Complete Architectural Works

- photos of 1890 Bell Telephone Building, St. Louis

References

- ^ a b c d e f g Jay Wickersham and Christopher Milford, "Richardson's death, Ames's money, and the birth of the modern architectural firm" in Perspecta 47 (2014): 114-127.

- ^ "Shepley, George F." in Boston of To-day: A Glance at its History and Characteristics, ed. Richard Herndon (Boston: Post Publishing Company, 1892): 389.

- ^ a b Henry-Russell Hitchcock, The Architecture of H. H. Richardson and his Times (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1961): 287-289.

- ^ "Shepley, George Foster" in The National Cyclopedia of American Biography 22 (New York: James T. White & Company, 1932): 99.

- ^ Bainbridge Bunting, Harvard: An Architectural History, ed. Margaret Henderson Floyd (Cambridge: Belknap Press, 1985): 124.

- ^ "Personal" in Inland Architect and Building News 18, no. 6 (January 1892): 79.

- ^ "Architects' Removals, etc." in American Architect and Building News 69, no. 1281 (July 14, 1900): x.

- ^ "Sarah E. Rutan, executrix, vs. Charles A. Coolidge" in Massachusetts Reports 241 (Boston: Little, Brown & Company, 1923): 584-600.

- ^ "George C. Shattuck dies at Exeter, N. H." Boston Globe, September 5, 1923.

- ^ "Charles Hodgdon," Chicago Tribune, November 26, 1953.

- ^ Economist 53, no. 6 (February 6, 1915): 239.

- ^ "Personals" in American Architect 108, no. 2066 (July 28, 1915): 62.

- ^ "Henry Shepley dies, noted hub architect," Boston Globe, November 25, 1962.

- ^ "Francis V. Bulfinch, architect, engineer, 84," Boston Globe, September 26, 1963.

- ^ "Lewis B. Abbott," Daily Evening Item, June 29, 1965.

- ^ "Coolidge, Charles Allerton" in The National Cyclopaedia of American Biography C (New York: James T. White & Company, 1930): 521.

- ^ Architectural Record 67, no. 5 (November 1930): 200.

- ^ Edgar J. Driscoll Jr., "Architect J. P. Richardson," Boston Globe, September 16, 1979.

- ^ Tom Lang, "James F. Clapp Jr., architect and amateur numismatist; at 89," Boston Globe, February 25, 1998.

- ^ Anastasia Goodstein, "Service for Sherman Morss, 84; architect, formerly of Beverly," Boston Globe, April 28, 1996.

- ^ Bryan Marquand, "Jean Paul Carlhian, 92; architect taught at Harvard," Boston Globe, November 30, 2012.

- ^ "Hugh Shepley," Boston Globe, September 10, 2017.

- ^ "Otis B. Robinson, at 82; architect for college, religious buildings," Boston Globe, April 22, 1999.

- ^ "Mathey, George R.," Boston Globe, August 23, 2020.

- ^ Julia Heskel. Shepley Bulfinch Richardson and Abbott: Past to Present (Boston: Shepley, Bulfinch, Richardson & Abbott Inc., 1999): 85 and 95-99.

- ^ Edgar J. Driscoll Jr., "Henry Richardson Shepley designed Margraten cemetery: Queen of Netherlands honors hub architect," Boston Globe, April 2, 1961.

- ^ Vincent Scully, "Foreword" in Shepley Bulfinch Richardson and Abbott: Past to Present (Boston: Shepley, Bulfinch, Richardson & Abbott Inc., 1999): 5.

- ^ Cambridge Tribune, July 9, 1904, 5.

- ^ Sally B. Woodbridge, John Galen Howard and the University of California (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002)

- ^ "Keene, Arthur Simpson" in American Architects Directory (New York: R. R. Bowker Company, 1956): 290.

- ^ "Noyes, Eliot Fette" in American Architects Directory (New York: R. R. Bowker Company, 1956): 408.

- ^ "Stone, Edward Durell" in American Architects Directory (New York: R. R. Bowker Company, 1956): 540.

- ^ a b c d e f Potter, Janet Greenstein (1996). Great American Railroad Stations. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 66, 81, 85, 92, 97, 190, 396. ISBN 9780471143895.

- ^ Liebs, Chester H. (July 1970). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Albany Union Station". Archived from the original on September 14, 2011. Retrieved April 18, 2009. and Accompanying two photos, exterior, from 1905 and undated

- ^ Lovecraft, H. P. (October 1, 2013). The Thing on the Doorstep and Other Weird Stories. Penguin. ISBN 9781101663035.

- ^ Ochsner, Jeffrey Karl (June 1988). "Architecture for the Boston & Albany Railroad: 1881-1894". Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 47 (2): 109–131. doi:10.2307/990324. JSTOR 990324.

External links

Media related to Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge at Wikimedia Commons