Shanghai Municipal Police

| Shanghai Municipal Police | |

|---|---|

| |

Flag of the Shanghai Municipal Council | |

| Abbreviation | SMP |

| Motto | Latin: Omnia Juncta In Uno All joined as one |

| Agency overview | |

| Formed | September 1854 |

| Dissolved | 31 July 1943 |

| Employees |

|

| Jurisdictional structure | |

| Operations jurisdiction | Shanghai International Settlement |

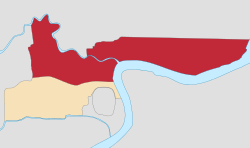

| |

| Map of police area (red) | |

| Size | 22.598 km2 (8.725 sq mi) |

| Population | 1,074,794m (1934) |

| Legal jurisdiction | Shanghai International Settlement |

| Governing body | Shanghai Municipal Council |

| General nature | |

| Operational structure | |

| Headquarters | Central Police Station, Foochow Road, Shanghai |

| Child agencies |

|

| Facilities | |

| Stations | 14 |

| Shanghai Municipal Police | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 上海公共租界工部局警務處 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 上海公共租界工部局警务处 | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | Shanghai Public Foreign Concession Ministry of Works Office Police Affairs Department | ||||||||

| |||||||||

The Shanghai Municipal Police (SMP; Chinese: 上海公共租界工部局警務處) was the police force of the Shanghai Municipal Council which governed the Shanghai International Settlement between 1854 and 1943, when the settlement was retroceded to Chinese control.

Initially composed of Europeans, most of them Britons, the force included Chinese after 1864, and was expanded over the next 90 years to include a Sikh Branch (established 1884), a Japanese contingent (from 1916) and a volunteer part-time special police (from 1918). In 1941, it acquired a Russian Auxiliary Detachment (formerly the Russian Regiment of the Shanghai Volunteer Corps).

History

Origins

The first detachment of 31 Europeans, effectively borrowed from the Hong Kong Police and led by Samuel Clifton, was recruited almost immediately after the formation of the Shanghai Municipal Council (SMC). These men were on patrol by September 1854.[2] Further men were recruited from the Royal Irish Constabulary, London's Metropolitan Police and from the military presence in Shanghai itself, while a structure for recruitment of Britons in the United Kingdom eventually came about through the Shanghai Municipal Council's London agents, John Pook & Co. Once formalised, a steady stream of young men was recruited to serve in Shanghai. Promotion from the lower ranks of the force was, however, limited. Most of the force's commanders were recruited from British domestic or colonial police forces, although a cadre of young British men was recruited as cadets, and held senior ranks in the force in the 1910s-'30s.[3]

In 1936, the last year of near-normal peacetime policing, the force totaled 4,739, men with 3,466 in the Chinese Branch, 457 serving in the Foreign Branch (predominantly British), 558 in the Sikh Branch and 258 in the Japanese Branch.[4]

Though the force was mostly occupied in the routine business of crime prevention, detection, and traffic control, it was also seen as the Settlement's first line of defense against Chinese nationalist activity. After the failure of the 1913 Second Revolution against the autocratic presidency of Yuan Shikai, the settlement was increasingly troubled by armed crime. In the build-up to, and aftermath of, the 1926–27 Nationalist Revolution, the force also struggled to contain a wave of armed robberies and politically motivated kidnappings. Throughout the 1930s, it faced challenges from the Nationalist Government and the police force of the (Nationalist Chinese) City Government of Shanghai, particularly over rights to operate outside the historical bounds of the Concession and in cases of extraterritoriality.

World War II and disbandment

Between the Japanese occupation of China in August 1937 and the attack on Pearl Harbor on 8 December 1941, the International Settlement along with the French Concession became the only neutral areas in east China. In this crowded and officially neutral enclave, the SMP struggled to maintain order in the face of a wave of increasingly violent terrorist bombings and reprisals between the Chinese and the Imperial Japanese Army and their collaborators. With the occupation of the Settlement in December 1941 the police came under Japanese control. Although a number of British officers were arrested as political prisoners and interned in Shanghai's Haiphong Road camp, most British staff in the SMP's Foreign Branch had no choice but to stay in their posts until their eventual dismissal and internment in February/March 1943. The SMP continued after this date, and was incorporated into the police force of the amalgamated Municipality of Shanghai in mid-1943. White Russian, Chinese, Japanese, and Indian (many of the latter being dismissed in 1944-45) staff continued to serve, as did some European personnel from Axis or neutral states.

Interned officers of the SMP had expected to return to their duties at the end of the war but the conclusion of the 1943 British-Chinese Treaty for the Relinquishment of Extra-Territorial Rights in China confirmed the abolition of the International Settlement. The post-war city police bureau continued the employment of a steadily declining number of the former SMP's Russian cadre, although all Chinese staff remained in post.[5] Foreign members of the SMP were dispersed, some to take up police, civilian or military employment elsewhere. Records in Shanghai indicate that some surviving Chinese personnel of the SMP were investigated as "counter-revolutionary" elements following the communist revolution in 1949.[6]

Legacy

The SMP retains the legacy as a pioneer in the field of police work, and many of its past members remain internationally renowned due to their contributions in the fields of policing and self-defence. Particularly well documented is the SMP's response to a staggering rise in armed crime, whereby serving officers such as William E. Fairbairn and Dermot 'Pat' O'Neil, working with volunteer "Special" personnel such as Eric A. Sykes, developed innovative combat pistol shooting, hand-to-hand combat skills and knife fight training.

As a result of the catastrophic policing failure of 30 May 1925, when Sikh and Chinese members of the SMP were ordered to open fire on Chinese demonstrators and thereby precipitated the nationwide anti-imperialist May Thirtieth Movement (五卅运动), the SMP developed myriad riot control measures. These techniques led to the introduction of Shanghai's "Reserve Unit" by Assistant Commissioner Fairbairn—the first modern SWAT team.[7] The skills developed in Shanghai have been adopted and adapted by both international police forces and clandestine warfare units. William Fairbairn was again the central figure, not only leading the Reserve Unit but teaching his new methods to law enforcement agencies in the United States, Cyprus, and Singapore.[citation needed]

Special Branch

A political policing unit had existed within the SMP from 1898, the so-called Intelligence Office, but this was renamed Special Branch in 1925 aligning with the form used throughout the British Commonwealth.[citation needed]

The office's greatest coup was the arrest of Jakob Rudnik (a.k.a. Hilaire Noulens) and his wife Tatiana Moissenko on 15 June 1931. The arrest, the result of close co-ordination with the Special Branches in Singapore, MI6 and French colonial intelligence, broke up the Comintern's secret International Liaison Department in the city. The SMP also correctly identified Richard Sorge as a member of the Third International; he was resident in the city from 1930 to 1933.[8] After 1928, Special Branch worked closely with Kuomintang intelligence services, helping to destroy and disperse much of the urban base of the Chinese Communist Party by 1932. The Special Branch's archive was acquired by the Central Intelligence Agency in 1949 and was eventually opened to researchers in the 1980s, although the files had clearly been weeded to remove material that might compromise some figures with a Shanghai past.

Shanghai police ranks

The Shanghai Municipal Police used police ranks based along British lines, and owed much to the Victorian rank-structure of the Metropolitan Police Force. From lowest to highest, the ranks were:

- Constable (post-1929, Probationary Sergeant)

- Sergeant

- Sub-Inspector

- Inspector

- Chief Inspector

- Superintendent

- Assistant Commissioner

- Deputy Commissioner

- Commissioner of Police (pre-1919, Captain-Superintendent)

Police stations

Between 1854 and the police's effective end in 1943, some 14 police stations were in use at various times.

- Central Station (1854-1943): Foochow Road

- Louza Station (1860-1943): Nanking Road, scene of the May 30 Movement on May 30, 1925

- Bubbling Well Road Station (1884-1943)

- Sinza Road Station (1899-1943)

- Gordon Road Station (1909–43)

- Chungdu Road Station (1933–43)

- Pootoo Road Station (1929–43)

- Hongkew Station (1861-1943)

- West Hongkew Station (1898-1943)

- Yangtszepoo Station (1891-1943)

- Wayside Station (1903–43)

- Arnold Road Station (1907–43)

- Yulin Road Station (1925–43)

- Dixwell Road Station (1912–43)

The 1930s Longchang apartments building, a former dormitory complex for Chinese constables and their families, is now a government-protected building.

Force commanders

- Samuel Clifton (Superintendent 1854–60), resigned after charges of embezzlement were "not proved" in court (North China Herald, 24 November 1860).

- William Ramsbottom (still titled Inspector in February 1862, though Superintendent from 19 April 1861). Late Sgt.-Major, 2nd Queen's. Resignation submitted due to ill health, 9 October 1863.

- Charles E. Penfold (Superintendent, 19 April 1864-85).

- James Painter McEuen (Captain Superintendent, 6 March 1885 to 25 July 1896), previously a Royal Navy captain and Hong Kong Harbour Master, invalided, died on way home, Yokohama.

- Donald Mackenzie (Deputy Superintendent, also acting Captain Superintendent 16 September 1896-98).

- Pierre B. Pattison (Captain Superintendent, 12 Feb 1898[9]-30 September 1900), on secondment from Royal Irish Constabulary, but denied extension for apparent political reasons.

- G. Howard (Chief Inspector, Acting i/c 1 October 1900 – 8 March 1901).

- Alan Maxwell Boisragon (Captain Superintendent, 8 March 1901 – 20 September 1906), forced to resign after Mixed Court Riot of 1905. Boisragon had been one of the two survivors of the 1897 massacre, which prompted the British Benin Expedition.

- Kenneth John McEuen (acting i/c Sept 1906-August 1907).

- Col. Clarence Dalrymple Bruce (Captain Superintendent, 7 August 1907-13), forced to resign after being scapegoated for SMC attempt to annex Zhabei (Chapei) during the Second Revolution.

- Alan Hilton-Johnson (acting Captain Superintendent 1914), resigned to serve in British Army during Great War.

- Kenneth John McEuen (Captain Superintendent, 1914–25), forced to retire after May 30 incident (son of J.P. McEuen).

- Edward Ivo Medhurst Barrett (Commissioner of Police, 1925–29), forced to resign.

- Reginald Meyrick Jullion Martin (Extra Commissioner, 1929–31, until F.W. Gerrard appointed permanently to post).

- Frederick Wernham Gerrard (Commissioner of Police, 7 October 1929-38), retired.

- Kenneth Morrison Bourne (Commissioner of Police, 29 March 1938 – August 1941). With the support of Deputy Commissioner Henry Malcolm Smyth, Bourne departed on furlough to take his sons to school in North America and shifted towards a position in MI6. For much of the war Bourne worked for the British Security Executive in New York. In February 1945 he was appointed to take charge of the Chinese Intelligence section of the Government of India’s intelligence bureau.[10]

- Henry Malcolm Smyth, OBE[11] (Deputy Commissioner of Police, 1938–42; acting Commissioner, August 1941-February 42). Resigned due to Japanese Occupation; Advisor to (Japanese) Commissioner of Police Watari 21 February 1942 – 10 August 1942. Then as a result of a special arrangement made with the Japanese, Smyth and over 100 senior Shanghai Municipality Civil Servants and Police Officers were repatriated to the neutral Portuguese colonial port of Lorenco Marques.[12]

- Masami Watari (渡正監, Commissioner of Police from 19 February 1942) - 1 August 1943. International Settlement retroceded, and with SMP absorbed into Greater Shanghai Municipality.

Uniforms

For most of their existence, the SMP wore uniforms that were British or British colonial in style. These included custodian helmets for European police until the early 1900s. Uniforms were dark blue serge in winter with khaki drill (including shorts or slacks) in summer. Sikh personnel wore red turbans while Chinese members of the force were distinguished by the conical Asian hat shown in the 1908 group photo above, until about 1919. After this date, Chinese and European police wore the same dark blue peaked cap with the coat of arms of the International Settlement as a badge. Pith helmets were often worn in hot weather. Sam Browne belts were worn by officers carrying sidearms.[13]

Awards

Members of the SMP were made eligible for several medals for service by the Municipal Council during its history. In addition to being eligible for awards from members' own native countries, these awards held official status and could be worn with other medals with the status of a foreign award. These medals included:

Shanghai Municipal Police Distinguished Conduct Medal, created in 1900, was presented in Class I and Class II, and was awarded for gallantry and conspicuous service whilst serving the SMP. Citations for recipients often referred to their "courage and devotion to duty". The medal was roughly equivalent to its British counterpart of the same name and its medal ribbon was the same as the Distinguished Service Order.

Shanghai Municipal Police Distinguished Conduct Medal, created in 1900, was presented in Class I and Class II, and was awarded for gallantry and conspicuous service whilst serving the SMP. Citations for recipients often referred to their "courage and devotion to duty". The medal was roughly equivalent to its British counterpart of the same name and its medal ribbon was the same as the Distinguished Service Order. Shanghai Jubilee Medal, created in 1893, it was distributed as part of the 50th Jubilee celebrations on 17 November 1893, being the anniversary of the arrival of the first British Consul after the Treaty of Nanking. Cast in silver, the medal consists of the municipal seal and the text "17 November 1843" on the obverse with a stylised shield engraved with the recipient's name and the text "Shanghai Jubilee. November 17, 1893." name between a steamship and two Chinese dragons on the reverse.

Shanghai Jubilee Medal, created in 1893, it was distributed as part of the 50th Jubilee celebrations on 17 November 1893, being the anniversary of the arrival of the first British Consul after the Treaty of Nanking. Cast in silver, the medal consists of the municipal seal and the text "17 November 1843" on the obverse with a stylised shield engraved with the recipient's name and the text "Shanghai Jubilee. November 17, 1893." name between a steamship and two Chinese dragons on the reverse. Shanghai Municipal Police Long Service Medal, created in 1910, was awarded for long service. Bars for additional periods of service were also awarded. Cast in silver, the medal consists of the SMP seal on the obverse and the recipient's name and the text "For Long Service" on the reverse. The Ribbon consisted of a gold inner stripe with two inner white stripes and two black outer stripes.

Shanghai Municipal Police Long Service Medal, created in 1910, was awarded for long service. Bars for additional periods of service were also awarded. Cast in silver, the medal consists of the SMP seal on the obverse and the recipient's name and the text "For Long Service" on the reverse. The Ribbon consisted of a gold inner stripe with two inner white stripes and two black outer stripes. Shanghai Municipal Police Long Service Medal (Specials), created in 1929, was awarded for long service in the voluntary branch of the SMP. Bars for additional periods of service were also awarded. While the medal was the same as the regular long service medal, the Ribbon consisted of three combined small versions of the regular long service ribbon.

Shanghai Municipal Police Long Service Medal (Specials), created in 1929, was awarded for long service in the voluntary branch of the SMP. Bars for additional periods of service were also awarded. While the medal was the same as the regular long service medal, the Ribbon consisted of three combined small versions of the regular long service ribbon. Shanghai Municipal Council 1937 Service Medal, created in 1937, was awarded to members of the Volunteer Corps, Police and civilians who had participated in operations protecting the International Settlement during the Japanese invasion of Shanghai in late 1937. An eight-pointed Brunswick star in bronze, the medal consists of the municipal seal on the obverse and the text "For Service Rendered August 12th to November 12th, 1937" on the reverse.

Shanghai Municipal Council 1937 Service Medal, created in 1937, was awarded to members of the Volunteer Corps, Police and civilians who had participated in operations protecting the International Settlement during the Japanese invasion of Shanghai in late 1937. An eight-pointed Brunswick star in bronze, the medal consists of the municipal seal on the obverse and the text "For Service Rendered August 12th to November 12th, 1937" on the reverse. Japanese/SMC Volunteer Police Medal, created in 1943 while the Shanghai International Settlement was controlled by Japanese occupation forces, recognised the service of Japanese police officers prior to the disbandment of the Shanghai Municipal Police on 31 July 1943. An eight-pointed Brunswick star, the medal consisted of the SMP badge on the obverse and five rows of raised Japanese characters honoring the bravery of the SMP on the reverse. The medal featured a maroon ribbon.

Japanese/SMC Volunteer Police Medal, created in 1943 while the Shanghai International Settlement was controlled by Japanese occupation forces, recognised the service of Japanese police officers prior to the disbandment of the Shanghai Municipal Police on 31 July 1943. An eight-pointed Brunswick star, the medal consisted of the SMP badge on the obverse and five rows of raised Japanese characters honoring the bravery of the SMP on the reverse. The medal featured a maroon ribbon.

Bibliography

- Robert Bickers, Empire Made Me: An Englishman Adrift in Shanghai (London, 2003 ISBN 978-0-14-101195-0; New York, 2004 ISBN 0-231-13132-1).

- Robert Bickers, 'Who were the Shanghai Municipal Police, and why where they there? The British Recruits of 1919', in Robert Bickers and Christian Henriot (eds), New Frontiers: Imperialism's new Communities in East Asia 1842-1953 (2000), pp. 170–191

- Guide to the Scholarly Resources Microfilm Edition of the Shanghai Municipal Police Files, 1894–1949, with an introduction by Marcia R. Ristaino. (Wilmington, Delaware: Scholarly Resources Inc., 1984?)

- Peter Robins, The Legend of W. E. Fairbairn: Gentleman and Warrior, The Shanghai Years, Research by Robins, Peter and Tyler, Nicholas; Compiled and Edited by Child, Paul R. (Harlow, 2005).

- Frederic Wakeman Jr., Policing Shanghai, 1927-1937 (Berkeley, 1995).

- Frederic Wakeman Jr., The Shanghai Badlands: Wartime Terrorism and Urban Crime, 1937-1941 (Cambridge, 1996).

- Frederic Wakeman Jr., ‘Policing Modern Shanghai’, China Quarterly 115 (1988), 408–440.

- Bernard Wasserstein, Secret War in Shanghai (London, 1999)

Memoirs

- E.W. Peters, Shanghai Policeman (London: Rich & Cowan, 1937). Peters was dismissed from the force after being found not guilty (with a colleague) of the killing of an indigent Chinese man. The volume is part policing memoir, part apologia.

- Ted Quigley, A Spirit of Adventure: The Memoirs of Ted Quigley (Lewes: The Book Guild Ltd., 1994). Quigley served in the SMP from 1938 to 1942.

- John Sanbrook, In My Father's Time: A Biography (New York: Vantage Press, 2008). A memoir of John (Jack) Sanbrook, who served in the force 1930–42, and then after internment in War Crimes investigation.

- Maurice Springfield, Hunting Opium and Other Scents (Halesworth: Norfolk and Suffolk Publicity, 1966). Springfield was a senior officer in the force and led its anti-opium squad. Most of the book is concerned with hunting.

See also

- Empire Made Me: An Englishman Adrift in Shanghai is a 2003 biography of the Shanghai policeman Richard Maurice Tinkler by British historian Robert Bickers.

- Shanghai Municipal Public Security Bureau (now)

References

- ^ Pages 229 & 231, "Red Turbans on the Bund: Sikh Migrants, Policemen and Revolutionaries in Shanghai 1886-1945", Cao Yin, National University of Singapore 2016

- ^ North China Herald, 2 September 1854, p. 8.

- ^ Robert Bickers, Empire Made Me, pp. 31-32

- ^ Shanghai Municipal Council, "Annual Report 1936"

- ^ Robert Bickers, Empire Made Me, pp. 312-322

- ^ Robert Bickers, Empire Made Me, p. 15

- ^ Leroy Thompson (24 October 2012). The World's First SWAT Team: W. E. Fairbairn and the Shanghai Municipal Police Reserve Unit. Frontline Books. pp. 77–. ISBN 978-1-78303-437-6.

- ^ Records of the Shanghai Municipal Police, "Foreign Agents of the Third International, D4718" May 18, 1933, National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 263, Entry A1-02, 190/24/30/06, Box 37

- ^ "Meetings: The Shanghai Municipal Council", North China Herald, Shanghai, 14 March 1898, p.24

- ^ Murphy, CJ (2016). "Constituting a problem in themselves: countering covert Chinese activity in India : the life and death of the Chinese Intelligence Section, 1944-1946". Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History. 44 (6): 928–951. doi:10.1080/03086534.2016.1227029. S2CID 151482769.

- ^ "DNW Auction Archive". Dix Noonan Webb Ltd. March 25, 2013. Retrieved Jan 6, 2021.

- ^ "Dix Noonan Webb Ltd Auction Archive".

- ^ Harriet Sergeant, Shanghai, p. 146

External links

- Shanghai Municipal Police Database of staff, with dates of service where known, searchable on China Families platform.

- Records Of The Shanghai Municipal Police 1894-1949 collection of files on the Internet Archive from NARA RG 263.

- Wallace Kinloch obituary

- Historical Photographs of China Resource includes several hundred digitised images of Shanghai Municipal Police, or taken or formerly owned by policemen.

- Shanghai Municipal Police Archive Wiki - Collecting metadata and citations related to individual police files.