Separation of Queensland

The Separation of Queensland was an event in 1859 in which the land that forms the present-day State of Queensland in Australia was excised from the Colony of New South Wales and created as a separate Colony of Queensland.

History

European settlement of Queensland began in 1824 when Lieutenant Henry Miller, commanding a detachment of the 40th Regiment of Foot, founded a convict outpost at Redcliffe. The settlement was transferred to the north bank of the Brisbane River the following year and continued to operate as a penal establishment until 1842, when the remaining convicts were withdrawn and the district opened to free settlement. By then squatters had already established themselves on the Darling Downs, far distant from the seat of the New South Wales government in Sydney. Agitation soon commenced for the creation of a separate northern colony which could look after local interests, with the clamour being no less apparent in the fledgling township of Brisbane.[1]

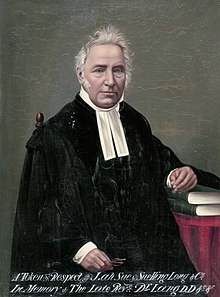

In the vanguard of those seeking representative government was the Reverend John Dunmore Lang, representative for Moreton Bay in the New South Wales Legislative Council. Lang's call for the creation of a northern colony in 1844 was defeated in the Council by 26 votes to seven, and matters were held in abeyance until 1850 when the British Parliament passed the Australian Colonies Government Act, which enabled the creation of new Australian colonies with a similar form of government to New South Wales. In other words, they would have a bicameral parliament watched over by a vice-regal representative. Importantly, specifically mentioned were Port Phillip and Moreton Bay as districts which were likely to become colonies in the foreseeable future. The Act inspired Lang to renewed efforts, and between 1851 and 1854 he held nine meetings to gain further support for separation. He was, in fact, preaching to the converted as the inhabitants of the northern district had been increasingly neglected by the government in Sydney.[1]

Yet while they could reach consensus on the need for separation, whether a new colony would be free or unfree became a divisive issue. Lang and the majority of townspeople supporters favoured free immigration. The powerful squatting fraternity was heavily reliant on cheap labour and so advocated a renewal of convict transportation. While urban growth in Brisbane and Ipswich finally dictated for the former, there was still disagreement over where a new capital should be located. Brisbane, Toowoomba, Cleveland, Gayndah, Gladstone, Ipswich and Rockhampton were all potential candidates favoured by parochial interests. Brisbane eventually emerged victorious, and the reality of a new colony moved a step closer in 1856, when the British government agreed that the time was ripe to create a new northern colony.[1]

Among other things there was uncertainty over the location of a southern border. Lang was among many others who believed that the Northern Rivers should become part of a northern colony; the New South Wales Government disagreed, and when Queen Victoria finally signed the Letters Patent to create Queensland on 6 June 1859 at Osborne House,[2] the border was fixed at 28 degrees south.

The following month, unofficial news was received that the Secretary of State for the Colonies, Sir Edward Bulwer-Lytton, had appointed Sir George Bowen to be the colony's first Governor of Queensland. Bowen had recently served as Britain's Lord High Commissioner of the Ionian Islands near Greece, and was to have a distinguished career in the Colonial Office. While both the Letters Patent and the Order-in-Council appointing Bowen as Governor were duly published by the New South Wales Government, separation could not be accomplished until the Letters Patent had also been published in Queensland. As Governor Bowen was due to arrive on 6 December 1859 with the Letters Patent formally proclaiming the new colony, a reception committee was organised as early as September to arrange the celebrations.[1]

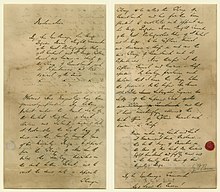

Inclement weather intervened meaning Governor Bowen did not arrive until the evening of 9 December 1859. The following day Governor and Lady Bowen were welcomed by an estimated crowd of 4,000 exultant colonists when they stepped ashore at the Botanic Gardens in Brisbane.[3] They were then conveyed by carriage to the temporary Government House, a building which now serves as the deanery of St John's Cathedral. After ascending to the balcony, the resident Supreme Court Judge, Justice Alfred Lutwyche administered Governor Bowen's oath, after which the Queen's Commission was read to the assembled throng by the newly appointed Colonial Secretary, Robert Herbert. The formalities concluded with the proclamation of the Letters Patent being read by Governor Bowen's acting private secretary, Abram Moriarty, who was to become the new colony's first civil servant after being appointed Under Colonial Secretary on 15 December 1859.[1]

The Letters Patent were published in the inaugural issue of the Queensland Government Gazette on 10 December 1859, and this has given rise to confusion over whether 10 December 1859 should be remembered as Separation Day or Proclamation Day. The former may be preferred, for it was only with the publication of the Letters Patent in Queensland that separation became a legal reality, though it can be equally accepted that this was also an official proclamation of their content.[1]

On 10 December 1859, Bowen also appointed an Executive Council to operate as a provisional government until a parliament had been elected. Under the terms of separation, however, it was left for Sir William Denison, Governor of New South Wales, to appoint 11 members to the first Queensland Legislative Council in May 1860 for a term of five years. Bowen was to appoint their successors for life, and from the outset the nominee character of the Upper House proved highly unpopular. Attempts to amend the Constitution to make the Upper House elected were to continue until the Legislative Council was finally abolished in 1922.[1]

However, the Queensland Legislative Assembly had 26 elected members sat for the first time on 22 May 1860.[4] In Queensland's first parliament, there was little evidence of the party politics, which would not begin to emerge until the second elections were held in 1863. Instead, they acted with a considerable degree of unanimity to pass legislation that set Queensland on its future course. The agenda largely revolved around land and immigration, primary and secondary education, extension of voting rights, state aid to religion, the census, transport, primary industry and the provision of labour.[1]

Commemoration

Queensland Day is celebrated on 6 June every year, the anniversary of Queen Victoria signing the Letters Patent to create Queensland on 6 June 1859.

Separation Day was celebrated as a public holiday on 10 December from 1860 to 1920.[5]

In 2009, Queensland celebrated its sesquicentenary, known as Q150.

In 2009, as part of the Q150 celebrations, Queensland being proclaimed a new colony was announced as one of the Q150 Icons of Queensland for its role as a "Defining Moment".[6]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h Johnson, Murray. "The birth of modern Queensland". Queensland State Archives. State of Queensland. Archived from the original on 23 April 2019. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- ^ David Gibson (10 December 2015). "Proclamation Day, when Queensland became a new colony". Brisbane Times. Fairfax Media. Archived from the original on 14 February 2017. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- ^ "ARRIVAL & RECEPTION OF HIS EXCELLENCY". The Moreton Bay Courier. Vol. XIV, no. 810. Queensland, Australia. 13 December 1859. p. 2. Archived from the original on 25 February 2022. Retrieved 13 February 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "The birth of modern Queensland". Queensland State Archives. 19 November 2015. Archived from the original on 14 March 2016. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- ^ Roberts, Katy (9 December 2016). "Separation Day: the "true birth of Queensland"". State Library of Queensland. Archived from the original on 11 May 2021. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- ^ Bligh, Anna (10 June 2009). "PREMIER UNVEILS QUEENSLAND'S 150 ICONS". Queensland Government. Archived from the original on 24 May 2017. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

Attribution

![]() This Wikipedia article was originally based on "The birth of modern Queensland" (2008) by Dr Murray Johnson published by the State of Queensland under CC-BY 3.0 AU licence (accessed on 10 February 2015, archived on 10 February 2015).

This Wikipedia article was originally based on "The birth of modern Queensland" (2008) by Dr Murray Johnson published by the State of Queensland under CC-BY 3.0 AU licence (accessed on 10 February 2015, archived on 10 February 2015).

External links

- "Item ID1431975, The Proclamation of Queensland document". Queensland State Archives. Retrieved 10 February 2015. — images of original handwritten document

- "Item ID1431995, Transcript of the Proclamation of Queensland document". Queensland State Archives. Retrieved 10 February 2015. — images of transcription