Selkup people

чумэлӷу́ла, тюйкула, шё̄шӄула, сӱ̄ссыӷӯла, шöйӄумыт | |

|---|---|

Flag | |

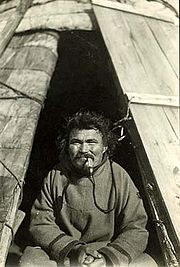

Selkup man from Obdorsk, Ob river | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 3,649[1] | |

| Languages | |

| Selkup languages | |

| Religion | |

| Shamanism, Russian Orthodoxy | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Nganasans, Nenets, Enets | |

The Selkup (Russian: селькупы, romanized: sel'kupy) are a Samoyedic speaking Uralic ethnic group native to Siberia.[2] They live in the northern parts of Tomsk Oblast, Krasnoyarsk Krai and Tyumen Oblast (with Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug).[3]

Ethnonyms

In Russian the Selkup call themselves Ostyak. This name is originally an exonym originating from the 17th century, when it was used to denote the Ob-Ugrian and Samoyed population of the Middle Ob region. By the end of the 20th century the name had been adopted by the Selkup as an indigenous name.[4] In the scientific literature from 1850s until the 1930s, the Selkup were exclusively called Ostyak-Samoyeds (остяко-самоеды, ostyako-samoyedy). This ethnonym has never been widely used.[citation needed]

The name Selkup was originally a self-designation of one group of Northern Selkups in the Taz River basin, but came to be applied to all the other local groups between the 1930s and 1980s.[5]

History

Selkups speak the Selkup language, which belongs to the Samoyedic languages of the Uralic language family.

The Selkups originated in the middle basin of the Ob River, from interactions between the aboriginal Yeniseian population and Samoyedic peoples that came to the region from the Sayan Mountains during the early part of the first millennium CE.[6] In the 13th century, the Selkups came under the sway of the Mongols. Around 1628, the Russians conquered the area and the Selkups were subjugated. The Selkups joined an uprising against Russian rule but were gunned down and defeated.[7]

In the 17th century, some of the Selkups relocated up north to live along the Taz River and Turukhan River. They were engaged mainly in hunting, fishing, and reindeer breeding. The arrival of Russian settlers to the area in the 18th century led to the Russians hunting down the reindeers of the Selkups which made breeding reindeer much more difficult.[7] During the same period, the Russians attempted to Russify and Christianize the Selkups.[7] However, many retained some of their ancient religious beliefs and customs.

During the Soviet period, the Selkups were forced to adopt a settled lifestyle and their traditional culture witnessed a severe decline. The Selkups have been facing cultural extinction and assimilation from Russian culture. They also suffer from racial discrimination, unemployment and alcoholism.[7]

According to a recent genetic study, subclade Q1a2a1-L54 was mainly found in Yeniseian (Ket) and Samoyedic (Enets and Selkup) speakers. Genetic evidence showed that Yeniseian and Samoyedic speakers had genetic affinities to northern Altaians with high frequencies of haplogroup Q-M242 (xL54), while southern Altaians had many L54 samples and showed similarities with Turkic-speaking populations (Dulik et al. 2012b; Battaglia et al. 2013; Flegontov et al. 2016). However, Yeniseian and Samoyedic samples in the latest study belonged to L54, which was different from the results of previous studies (xL54). In view of the time estimates the researchers postulated that Q1a2a1-L54 had migrated from the southern Altai region and was assimilated into Yeniseian and Samoyedic speaking populations during a recent historical period.[2]

Population and ethnic groups

According to the 2002 Census, there were 4,249 Selkups in Russia (4,300 in 1970). There were 62 Selkups in Ukraine, only one of whom is a native speaker of the Selkup language (Ukrainian Census 2001).

The modern Selkup form two geographically isolated groups, the Southern and Northern Selkups. The Southern Selkups, also called Narym Selkups, live mostly within the Tomsk Oblast.[5] The Northern Selkup moved north when Russians started colonizing Siberia. Movement towards north happened in several waves.[8]

The main Selkup settlements in Siberia are Krasnoselkup and Kargasok.

Culture

The Selkups traditionally engaged in hunting, fishing, and reindeer herding as subsistence. The Selkups also utilized dugout canoes to sail on rivers.[9]

In 1911-1912 and 1914, the expeditions of the Finnish linguist and ethnographer Kai Reinhold Donner (1888-1935) were engaged in studying the language, folklore, everyday culture and the traditional way of life of the Selkups.

Another famous Selkupologist was Eugene Helimski.

References

- ^ Russian Census 2010: Population by ethnicity (in Russian)

- ^ a b Huang, Y. Z.; Pamjav, H.; Flegontov, P.; Stenzl, V.; Wen, S. Q.; Tong, X. Z.; Wang, C. C.; Wang, L. X.; Wei, L. H.; Gao, J. Y.; Jin, L.; Li, H. (2017). "Dispersals of the Siberian Y-chromosome haplogroup Q in Eurasia". Molecular Genetics and Genomics. 293 (1): 107–117. doi:10.1007/s00438-017-1363-8. PMC 5846874. PMID 28884289.

- ^ "ВПН-2010". www.gks.ru. Retrieved 2021-10-09.

- ^ Napolskikh, Siikala & Hoppál 2007, p. 16.

- ^ a b Napolskikh, Siikala & Hoppál 2007, p. 15.

- ^ Flegontov, Pavel; Changmai, Piya; Zidkova, Anastassiya; Logacheva, Maria D.; Altınışık, N. Ezgi; Flegontova, Olga; Gelfand, Mikhail S.; Gerasimov, Evgeny S.; Khrameeva, Ekaterina E. (2016-02-11). "Genomic study of the Ket: a Paleo-Eskimo-related ethnic group with significant ancient North Eurasian ancestry". Scientific Reports. 6: 20768. arXiv:1508.03097. Bibcode:2016NatSR...620768F. doi:10.1038/srep20768. PMC 4750364. PMID 26865217.

- ^ a b c d "The Selkups". www.eki.ee. Red Book of the Peoples of the Russian Empire. Retrieved 2020-09-05.

- ^ Napolskikh, Siikala & Hoppál 2007, p. 20.

- ^ Forsyth, James (1994). A History of the Peoples of Siberia: Russia's North Asian Colony 1581-1990. Cambridge University Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-521-47771-0.

Sources

- Napolskikh, Vladimir; Siikala, Anna-Leena; Hoppál, Mihály, eds. (2007). Selkup Mythology. Encyclopaedia of Uralic Mythologies. Vol. 4. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó.

Further reading

- Sobanski, Florian (March 2001). "The southern Selkups of Tomsk Province before and after 1991". Nationalities Papers. 29 (1): 171–179. doi:10.1080/00905990120036448. S2CID 177457842.