Second Boer War concentration camps

| Second Boer War concentration camps | |

|---|---|

| Part of Second Boer War | |

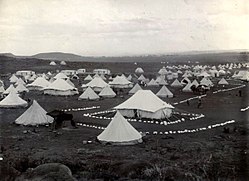

Tents in the Bloemfontein concentration camp | |

| Date | 1899–1902 |

Attack type | Internment |

| Deaths | Over 47,900 deaths: |

| Victims | 154,000 interned in British concentration camps |

| Perpetrators | British Empire, particularly Herbert Kitchener |

During the Second Anglo-Boer War (1899–1902), the British operated concentration camps in the South African Republic, Orange Free State, Natal, and the Cape Colony. In February 1900, Herbert Kitchener took command of the British forces and implemented some of the controversial tactics that contributed to a British victory.[3]

As the Boers used a 'guerrilla warfare' strategy, they lived off the land and used their farms as a source of food, thus making their farms a key item in their many successes at the beginning of the war. When Kitchener realized that a traditional warfare style would not work against the Boers, he began initiating plans that would later cause much controversy in the British public.[4][5]

Scorched-earth policy

According to historian Thomas Pakenham, in March 1901, Lord Kitchener initiated plans to deter guerrillas. In a series of systematic drives, organised like a sporting shoot, with success defined by a weekly 'bag' of killed, they captured and wounded Boers. They swept the country bare of everything that could give sustenance to the guerrillas including women and children. Large epidemics of diseases including measles, killed thousands, affecting children the most. It was the clearance of civilians and uprooting a nation that came to dominate the last phases of the war.[6]

As Boer farms[7] were destroyed by the British under their "Scorched Earth" policy - including the systematic destruction of crops and the slaughtering or removal of livestock, the burning down of homesteads and farms to prevent the Boers from resupplying themselves from a home base, many tens of thousands of men, women, and children were forcibly moved into the camps.[8][9] This was not the first appearance of concentration camps, as the Spanish had used them in Cuba during and after the Ten Years' War. However, the Boer War concentration camp system was the first time a whole nation had been systematically targeted, and the first in which entire regions had been depopulated.[8]

Eventually, a total of 45 tented camps were built for Boer internees and 64 additional camps were built for black Africans. The vast majority of Boers who remained in the local camps were women and children. Between 18,000 and 26,000 women and children perished in these concentration camps due to diseases.[10]

The camps were poorly administered from the outset, and they became increasingly overcrowded when Lord Kitchener's troops implemented the internment strategy on a vast scale. Conditions were terrible for the health of the internees, mainly due to neglect, poor hygiene and bad sanitation.[11] The supply of all items were unreliable, partly because of the constant disruption of communication lines by the Boers. The food rations were meager, and there was a two-tier allocation policy, whereby families of men still fighting were routinely given smaller rations than others.[12] The inadequate shelter, poor diet, bad hygiene, and overcrowding led to malnutrition and endemic contagious diseases such as measles, typhoid, and dysentery to which the children were particularly vulnerable.[13] Due to a shortage of modern medicine facilities and medical mistreatment, many internees died.[14]

UK public opinion and political opposition

Although the 1900 UK general election, also known as the "Khaki election", had resulted in a victory for the Conservative government on the back of recent British victories against the Boers, public support quickly waned as it became apparent that the war would not be easy. Further unease developed following reports filtering back to Britain concerning the treatment of Boer civilians by the British. Public and political opposition to government policies in South Africa regarding Boer civilians was first expressed in Parliament in February 1901 in the form of an attack on the government by the Liberal Party MP David Lloyd George.[15]

Emily Hobhouse, a delegate of the South African Women and Children's Distress Fund, visited some of the camps in the Orange Free State from January 1901. In May 1901 she returned to England on board the ship, the Saxon. Alfred Milner, High Commissioner in South Africa, also boarded the Saxon for holiday in England but, unfortunately for both the camp internees and the British government, he had no time for Miss Hobhouse, regarding her as a Boer sympathizer and "trouble maker".[16] On her return, Emily Hobhouse did much to publicize the distress of the camp inmates. She managed to speak to the Liberal Party leader, Henry Campbell-Bannerman, who professed to be suitably outraged but was disinclined to press the matter, as his party was split between the imperialists and the pro-Boer factions.[17]

St John Brodrick, the Conservative secretary of state for war, first defended the government's policy by arguing that the camps were purely "voluntary" and that the interned Boers were "contented and comfortable", but was somewhat undermined as he had no firm statistics to back up his argument, so when his "voluntary" argument proved untenable, he argued that all measures being taken were "military necessities" and stated that everything possible was being done to ensure satisfactory conditions in the camps.

Hobhouse published a report in June 1901[18] that contradicted Brodrick's claim, and Lloyd George then openly accused the government of "a policy of extermination" directed against the Boer population. The same month Liberal opposition party leader Campbell-Bannerman took up the assault and answered the rhetorical question "When is a war not a war?" with his own rhetorical answer "When it is carried on by methods of barbarism in South Africa", referring to those same camps and the policies that created them.[19] The Hobhouse Report caused uproar both domestically and internationally.[20]

The Fawcett Commission

Although the government had comfortably won the parliamentary debate by a margin of 252 to 149, it was stung by the criticism. Concerned by the escalating public outcry, it called on Kitchener for a detailed report. In response, complete statistical returns from camps were sent out in July 1901. By August 1901, it was clear to government and opposition alike that Miss Hobhouse's worst fears were being confirmed – 93,940 Boers and 24,457 black Africans were reported to be in "camps of refuge" and the crisis was becoming a catastrophe as the death rates appeared very high, especially among the children.

The government responded to the growing clamor by appointing a commission.[a] The Fawcett Commission, as it became known was, uniquely for its time, an all-woman affair headed by Millicent Fawcett who despite being the leader of the women's suffrage movement was a Liberal Unionist and thus a government supporter and considered a safe pair of hands. Between August and December 1901, the Fawcett Commission conducted its own tour of the camps in South Africa. While it is probable that the British government expected the Commission to produce a report that could be used to fend off criticism, in the end it confirmed everything that Emily Hobhouse had said. Indeed, if anything the Commission's recommendations went even further. The Commission insisted that rations should be increased and that additional nurses be sent out immediately and included a long list of other practical measures designed to improve conditions in the camp. Millicent Fawcett was quite blunt in expressing her opinion that much of the catastrophe was owed to a simple failure to observe elementary rules of hygiene.

In November 1901, the Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain ordered Alfred Milner to ensure that "all possible steps are being taken to reduce the rate of mortality". The civil authority took over the running of the camps from Kitchener and the British command and by February 1902 the annual death-rate in the concentration camps for white inmates dropped to 6.9 percent and eventually to 2 percent. However, by then the damage had been done. A report after the war concluded that 27,927 Boers (of whom 24,074 [50 percent of the Boer child population] were children under 16) had died in the camps. In all, about one in four (25 percent) of the Boer inmates, mostly children, died.

"Improvements [however] were much slower in coming to the black camps".[21] It is thought that about 12 percent of black African inmates died (about 14,154) but the precise number of deaths of black Africans in concentration camps is unknown as little attempt was made to keep any records of the 107,000 black Africans who were interned.

The main decisions (or their absence) had been left to the soldiers, to whom the life or death of the 154,000 Boer and African civilians in the camps rated as an abysmally low priority. [It was only] ... ten months after the subject had first been raised in Parliament ... [and after public outcry and after the Fawcett Commission that remedial action was taken and] ... the terrible mortality figures were at last declining. In the interval, at least twenty thousand whites and twelve thousand coloured people had died in the concentration camps, the majority from epidemics of measles and typhoid that could have been avoided.[22][b]

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle had served as a volunteer doctor in the Langman Field Hospital at Bloemfontein between March and June 1900. In his widely distributed and translated pamphlet 'The War in South Africa: Its Cause and Conduct' he justified both the reasoning behind the war and handling of the conflict itself. He also pointed out that over 14,000 British soldiers had died of disease during the conflict (as opposed to 8,000 killed in combat) and at the height of epidemics he was seeing 50–60 British soldiers dying each day in a single ill-equipped and overwhelmed military hospital.

Kitchener's policy and the post-war debate

It has been argued that "this was not a deliberately genocidal policy; rather it was the result of [a] disastrous lack of foresight and rank incompetence on [the] part of the [British] military".[24] Scottish historian Niall Ferguson has also argued that "Kitchener no more desired the deaths of women and children in the camps than of the wounded Dervishes after Omdurman, or of his own soldiers in the typhoid-stricken hospitals of Bloemfontein."[25]

However, to Lord Kitchener and British High Command "the life or death of the 154,000 Boer and African civilians in the camps rated as an abysmally low priority" against military objectives.[citation needed] As the Fawcett Commission was delivering its recommendations, Kitchener wrote to St John Brodrick defending his policy of sweeps, and emphasizing that no new Boer families were being brought in unless they were in danger of facing starvation. This was disingenuous as the countryside had by then been devastated under the "Scorched Earth" policy (the Fawcett Commission in December 1901 in its recommendations commented that: "to turn 100,000 people now being held in the concentration camps out on the field to take care of themselves would be cruelty"[citation needed]) and now that the New Model counter insurgency tactics were in full swing, it made little sense to leave the Boer families by themselves in desperate conditions in the countryside.

It was according to one historian[who?] that "at [the Vereeniging negotiations in May 1902] Boer leader Louis Botha asserted that he had tried to send [Boer] families to the British, but they had refused to receive them"[citation needed]. Quoting a Boer commandant referring to Boer women and children made refugees by Britain's scorched-earth policy as saying, "Our families are in a pitiable condition and the enemy uses those families to force us to surrender .. and there is little doubt that that was indeed the intention of Kitchener when he had issued instructions that no more families were to be brought into the concentration camps[citation needed] [verify][sentence fragment]". Thomas Pakenham writes of Kitchener's policy U-turn,

No doubt the continued 'hullabaloo' at the death-rate in these concentration camps, and Milner's belated agreement to take over their administration, helped change Kitchener's mind [some time at the end of 1901]. ... By mid-December at any rate, Kitchener was already circulating all column commanders with instructions not to bring in women and children when they cleared the country, but to leave them with the guerrillas. ... Viewed as a gesture to Liberals, on the eve of the new session of Parliament at Westminster, it was a shrewd political move. It also made excellent military sense, as it greatly handicapped the guerrillas, now that the drives were in full swing. ... It was effective precisely because, contrary to the Liberals' convictions, it was less humane than bringing them into camps, though this was of no great concern to Kitchener.[26]

List of concentration camps

Afrikaner concentration camps

The exact number of incarcerated victims of the concentration camps for Afrikaners is estimated to number around 40,000 by May of 1902, the majority of which were women and children.[27][28] The total deaths in camps are officially calculated at 27,927 deaths.[29][30]

| White concentration camps | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Location | Dates | Deaths (total) |

| Aliwal North | Cape Colony | January 1901 - November 1902 | 712 |

| Balmoral | Transvaal Republic | July 1901 - December 1902 | 427 |

| Barberton | Transvaal Republic | February 1901 - December 1902 | 216 |

| Belfast | Transvaal Republic | February 1901 - December 1902 | 247 |

| Bethulie | Orange Free State | April 1901 - January 1902 | 1737 |

| Bloemfontein | Orange Free State | August 1900 - January 1903 | 1695 |

| Brandfort | Orange Free State | January 1901 - March 1903 | 1263 |

| Bronkhorstspruit | Transvaal Republic | c. 1901 | undisclosed |

| Colenso | Natal Colony | January 1902 - April 1902 | undisclosed |

| De Jagersdrift | Natal Colony | May 1901 - ? | undisclosed |

| Douglas | Cape Colony | October 1901 | undisclosed |

| East London | Cape Colony | March 1902 - August 1902 | undisclosed |

| Edenburg | Orange Free State | December 1900 - ? | undisclosed |

| Elandsfontein | Orange Free State | January 1901 - June 1901 | undisclosed |

| Ermelo | Transvaal Republic | undisclosed | undisclosed |

| Eshowe | Natal Colony | October 1901 - April 1902 | undisclosed |

| Harrismith | Orange Free State | November 1900 - May 1902 | 130 |

| Heidelberg | Transvaal Republic | January 1901 - December 1902 | 499 |

| Heilbron | Orange Free State | February 1901 - January 1903 | 602 |

| Howick | Natal Colony | January 1901 - October 1902 | 145 |

| Irene (PTA) | Transvaal Republic | December 1900 - February 1903 | 1179 |

| Isipingo (DBN) | Natal Colony | undisclosed | 22 |

| Jacobs Siding (DBN) | Natal Colony | February 1902 - January 1903 | 65 |

| Turffontein (JHB) | Transvaal Republic | December 1900 - October 1902 | 716 |

| Kabusi | Cape Colony | May 1902 - December 1902 | undisclosed |

| Kimberley | Cape Colony | January 1901 - January 1903 | 531 |

| Klerksdorp | Transvaal Republic | January 1901 - January 1903 | 786 |

| Kromellenboog | Natal Colony | February 1901 - December 1901 | undisclosed |

| Kroonstad | Orange Free State | September 1900 - January 1903 | 2000 |

| Krugersdorp | Transvaal Republic | May 1901 - December 1902 | 766 |

| Ladybrand | Orange Free State | April 1901 - June? 1902 | undisclosed |

| Ladysmith | Natal Colony | February 1902 - September 1902 | undisclosed |

| Lydenburg | Transvaal Republic | 1900 - 1902 | undisclosed |

| Mafeking | Cape Colony | July 1901 - December 1902 | undisclosed |

| Matjiesfontein | Cape Colony | October 1901 - ? | undisclosed |

| Merebank (DBN) | Natal Colony | September 1901 - December 1902 | 471 |

| Middelburg | Transvaal Republic | February 1901 - January 1903 | 1621 |

| Modder River | Cape Colony | June 1901 - ? | undisclosed |

| Mooi River | Natal Colony | Never occupied | N/A |

| Norvalspont | Orange Free State | February 1901 - October 1902 | 366 |

| Nylstroom | Transvaal Republic | May 1901 - March 1902 | 525 |

| Orange River Station (Hopetown/Doornbult) | Orange Free State | April 1901 - November 1902 | 209 |

| Pietermaritzburg | Natal Colony | August 1900 - December 1902 | 213 |

| Pietersburg | Transvaal Republic | May 1901 - January 1903 | undisclosed |

| Pinetown (DBN) | Natal Colony | April 1902 - August 1902 | undisclosed |

| Port Elizabeth | Cape Colony | November 1900 - November 1902 | 14 |

| Potchefstroom | Transvaal Republic | September 1900 - March 1903 | 1085 |

| Meintjieskop (PTA) | Transvaal Republic | January 1902 - December 1902 | undisclosed |

| Pretoria Rest Camp (PTA) | Transvaal Republic | April 1901 - 1902 | undisclosed |

| Reitz | Orange Free State | March 1901 - May 1901 | undisclosed |

| Springfontein | Orange Free State | February 1900 - January 1903 | undisclosed |

| Standerton | Transvaal Republic | December 1900 - January 1903 | 857 |

| Platrand (Standerton) | Transvaal Republic | February 1901 | undisclosed |

| Uitenhage | Cape Colony | April 902 - October 1902 | 9 |

| Vereeniging | Transvaal Republic | September 1900 - November 1902 | 156 |

| Viljoensdrif | Orange Free State | January 1901 - February 1901 | undisclosed |

| Volksrust | Transvaal Republic | February 1901 - January 1903 | 1009 |

| Vredefortweg | Orange Free State | February 1901 - September 1902 | 800 |

| Vryburg | Cape Colony | July 1901 - December 1902 | 251 |

| Vryheid | Natal Colony | July 1901 - 1902 | undisclosed |

| Warrenton | Cape Colony | March 1901 - July 1902 | undisclosed |

| Walerval Noord | Orange Free State | January 1901 - August 1901 | undisclosed |

| Wentworth (DBN) | Natal Colony | March 1902 - September 1902 | undisclosed |

| Winburg | Orange Free State | January 1901 - January 1903 | 487 |

Black African concentration camps

By May of 1902, when The Treaty of Vereeniging was signed, the total number of Black South Africans in concentration was recorded at 115,700.[31] The total Black deaths in camps are officially calculated at a minimum of 14 154.[32] 81% of the fatalities were children.[33]

Notes

- ^ A personal copy of Millicent Fawcett's report, together with extensive photographs and inserts, is available for consultation at The Women's Library, Old Castle Street, London E1 7NT, archive reference 7MGF/E/1

- ^ Somewhat higher figures for total deaths in the concentration camps are given some historians.[23]

- ^ "Black Concentration Camps during the Anglo–Boer War 2, 1900–1902 | South African History Online". www.sahistory.org.za. Retrieved 2021-09-01.

- ^ "To fully reconcile The Boer War is to fully understand the 'Black' Concentration Camps by Peter Dickens (The Observation Post), | South African History Online". www.sahistory.org.za. Retrieved 2021-09-01.

- ^ "Herbert Kitchener: The taskmaster | National Army Museum". National Army Museum.

- ^ "Methods of Barbarism", Archives of Empire, Duke University Press, pp. 683–685, 2003-12-31, doi:10.2307/j.ctv1220psq.85, retrieved 2023-12-28

- ^ Hobhouse, Emily (1902). The Brunt of the War, and where it Fell. Methuen & Company.

- ^ Pakenham 1979, p. 493.

- ^ "British Concentration Camps of the South African War 1900-1902". www2.lib.uct.ac.za. Retrieved 2024-11-19.

- ^ a b "Women and Children in White Concentration Camps during the Anglo-Boer War, 1900-1902 | South African History Online". www.sahistory.org.za.

- ^ Marks, S. (2015). The Concentration Camps of the Anglo-Boer War: A Social History. Journal of Southern African Studies, (5), 1133.

- ^ Wessels 2010, p. 32.

- ^ Hobhouse, Emily (1902). The Brunt of the War, and where it Fell. Methuen & Company.

- ^ Pakenham 1979, p. 505.

- ^ Judd & Surridge 2013, p. 195.

- ^ "Women and Children in White Concentration Camps during the Anglo-Boer War, 1900-1902 | South African History Online". www.sahistory.org.za. Retrieved 2023-10-07.

- ^ Rintala, Marvin (Spring 1988). "Made in Birmingham: Lloyd George, Chamberlain, and the Boer War". Biography. 11 (2). University of Hawai'i Press: 124–139. doi:10.1353/bio.2010.0580. JSTOR 23539369. S2CID 154239858 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Pakenham 1979, pp. 531–32, 536+

- ^ Crangle, John V; Baylen, Joseph O (1979). "Emily Hobhouse's Peace Mission, 1916 on JSTOR". Journal of Contemporary History. 14 (4): 731–744. doi:10.1177/002200947901400409. JSTOR 260184. S2CID 159719565.

- ^ Guardian Research Department (19 May 2011). "From the archive blog: 19 June 1901: The South African concentration camps". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- ^ Hattersley, Roy (2006). Campbell-Bannerman. Haus Publishing. pp. 79–80. ISBN 1-904950-56-6.

- ^ Rettenmaier, David (2017-12-22). "Hobhouse report on Second Boer War". editions.covecollective.org. Retrieved 2023-10-07.

- ^ Ferguson 2002, p. 235.

- ^ Pakenham 1979, p. 549

- ^ Spies 1977, p. 265.

- ^ Ferguson 2002, p. 250.

- ^ Pakenham 1979, p. 524

- ^ Pakenham 1979, pp. 461–572

- ^ "Women and Children in White Concentration Camps during the Anglo-Boer War, 1900-1902 | South African History Online".

- ^ "Second Anglo-Boer War - 1899 - 1902 | South African History Online".

- ^ "Engelse Concentratiekampen 1899-1902". 28 April 2015.

- ^ "Women and Children in White Concentration Camps during the Anglo-Boer War, 1900-1902 | South African History Online".

- ^ "Black Concentration Camps during the Anglo-Boer War 2, 1900-1902 | South African History Online".

- ^ "Black Concentration Camps during the Anglo-Boer War 2, 1900-1902 | South African History Online".

- ^ "Black Concentration Camps during the Anglo-Boer War 2, 1900-1902 | South African History Online".

References

- Ferguson, Niall (2002). Empire: The Rise and Demise of the British World Order and the Lessons for Global Power. Basic Books. p. 235.

- Judd, Denis; Surridge, Keith (2013). The Boer War: A History (2nd ed.). London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1780765914.excerpt and text search; a standard scholarly history

- Pakenham, Thomas (1979). The Boer War. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-394-42742-4.

- Spies, S.B. (1977). Methods of Barbarism: Roberts and Kitchener and Civilians in the Boer Republics January 1900 – May 1902. Cape Town: Human & Rousseau. p. 265.

- Wessels, André (2010). A Century of Postgraduate Anglo-Boer War (1899–1902) Studies: Masters' and Doctoral Studies Completed at Universities in South Africa, in English-speaking Countries and on the European Continent, 1908–2008. African Sun Media. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-920383-09-1.