Seated Liberty dollar

United States | |

| Value | 1 US dollar |

|---|---|

| Mass | 26.73 g |

| Diameter | 38.1 mm |

| Edge | Reeded |

| Composition | |

| Silver | 0.77344 troy oz |

| Years of minting | 1840–1873 |

| Mint marks | O, S, CC. Located beneath eagle on reverse. Philadelphia Mint specimens lack a mint mark. |

| Obverse | |

| Design | Liberty seated |

| Designer | Christian Gobrecht |

| Design date | 1840 |

| Reverse | |

| Design | A left-facing bald eagle. Without motto. |

| Designer | Christian Gobrecht |

| Design date | 1840 |

| Design discontinued | 1865 |

| |

| Design | With motto |

| Designer | Christian Gobrecht |

| Design date | 1866 |

| Design discontinued | 1873 |

The Seated Liberty dollar was a dollar coin struck by the United States Mint from 1840 to 1873 and designed by its chief engraver, Christian Gobrecht. It was the last silver coin of that denomination to be struck before passage of the Coinage Act of 1873, which temporarily ended production of the silver dollar for American commerce. The coin's obverse is based on that of the Gobrecht dollar, which had been minted experimentally from 1836 to 1839. However, the soaring eagle used on the reverse of the Gobrecht dollar was not used; instead, the United States Mint (Mint) used a heraldic eagle, based on a design by late Mint Chief Engraver John Reich first utilized on coins in 1807.

Seated Liberty dollars were initially struck only at the Philadelphia Mint; in 1846, production began at the New Orleans facility. In the late 1840s, the price of silver increased relative to gold because of an increase in supply of the latter caused by the California Gold Rush; this led to the hoarding, export, and melting of American silver coins. The Coinage Act of 1853 decreased the weight of all silver coins of five cents or higher, except for the dollar, but also required a supplemental payment from those wishing their bullion struck into dollar coins. As little silver was being presented to the US Mint at the time, production remained low. In the final years of the series, there was more silver produced in the US, and mintages increased.

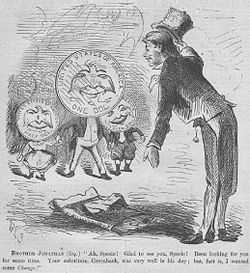

In 1866, "In God We Trust" was added to the dollar following its introduction to United States coinage earlier in the decade. Seated Liberty dollar production was halted by the Coinage Act of 1873, which authorized the trade dollar for use in foreign commerce. Representatives of silver interests were unhappy when the metal's price dropped again in the mid-1870s; they advocated the resumption of the free coinage of silver into legal tender, and after the passage of the Bland–Allison Act in 1878, production resumed with the Morgan dollar.

Background

The Mint Act of 1792 made both gold and silver legal tender; specified weights of each was equal to a dollar.[1] The United States Mint struck gold and silver only when depositors supplied metal, which was returned in the form of coin.[2] The fluctuation of market prices for commodities meant that either precious metal would likely be overvalued in terms of the other, leading to hoarding and melting; in the decades after 1792, it was usually silver coins which met that fate.[1] In 1806, President Thomas Jefferson officially ordered all silver dollar mintage halted, though production had not occurred since 1804.[3] This was done in part to prevent the coins from being exported to foreign nations for melting, causing a strain on the fledgling Mint for little gain.[3] Over the next quarter century, the silver coin usually struck for bullion depositors was the half dollar.[4] In 1831, Mint Director Samuel Moore requested that President Andrew Jackson lift the restriction against dollar coin production; the president obliged in April of that year.[5] Despite the approval to strike the coins, no silver dollars were minted until 1836.[5]

The Bureau of the Mint in the 1830s was undergoing a period of significant change, as new technologies were adopted. In 1828, the Mint, whose authorization had been subject to periodic renewal by Congress since its inception in 1792, was given permanent status.[6] A new building to house the Philadelphia Mint was authorized by Congress, and opened in 1832.[7] Congress adjusted the precious-metal content of US coins in 1834 and 1837, and was able to achieve a balance whereby US coins remained in circulation alongside those of foreign nations (mostly Spanish colonial pieces). In 1836, the first steam machinery was introduced at the Mint; previously coins had been struck by muscle power.[8] Congress had in 1835 authorized branch mints at Dahlonega in Georgia, Charlotte in North Carolina, and at New Orleans in Louisiana. The Charlotte and Dahlonega mints only struck gold, catering to miners in the South who sought to deposit that metal, but the New Orleans facility would also strike silver coins, including the Seated Liberty dollar.[9][10]

Gobrecht dollar

In mid-1835, newly appointed Mint Director Robert M. Patterson engaged artists Titian Peale and Thomas Sully to create new designs for American coinage.[11] In an August 1, 1835, letter, Patterson proposed that Sully create an obverse design consisting of Liberty seated on a boulder, holding a "liberty pole" in her right hand topped by a pileus, the headgear given by the Romans to an emancipated slave.[11] He also asked Sully to create a reverse design consisting of an "eagle flying, and rising in flight, amidst the constellation irregularly dispersed of twenty-four stars".[a][11] Patterson requested that the bird appear natural; he criticized the eagle designs then in use on the nation's coinage as being unnatural primarily because of the shield placed on the eagle's breast.[11] Mint Chief Engraver William Kneass prepared a sketch based on Patterson's conception, but suffered a stroke, leaving him partially paralyzed.[12] Later in 1835, Christian Gobrecht was hired at the Mint as a draftsman, die sinker, and assistant engraver to Kneass.[13] Although nominally a subordinate, Gobrecht would perform much of the engraving work for the Mint until Kneass' death in 1840, when Gobrecht was appointed chief engraver.[14]

Sully prepared sketches of the artwork, which Gobrecht used as a guide in engraving copper plates.[15] The plates were approved by various government officials, and the production of trial strikes began.[15] The design was not free from controversy; former Mint Director Samuel Moore had deprecated the use of the pileus. Quoting former president Thomas Jefferson, Moore had written to Secretary of the Treasury Levi Woodbury, "We are not emancipated slaves."[12]

Following a series of trial strikes and modifications through 1836, the first of what would come to be known as the Gobrecht dollars were minted in December of that year.[16] The dollars of 1836 were minted with a silver fineness of .892 (89.2%) silver,[16] a specification set forth in the 1792 act.[17] The mandated fineness of US silver coins was changed from .892 to .900 (90%) by the Coinage Act of 1837, passed on January 18, 1837; subsequent Gobrecht dollars were struck in .900 silver.[11] Beginning in 1837, an adaptation of the obverse of the Gobrecht dollar, depicting a seated Liberty, was used on the smaller silver coins (from half dime to half dollar), with Gobrecht's modification of Reich's heraldic eagle on the reverse of the quarter and half dollar. Except on the half dime, abolished in 1873, the designs would remain on those coins for over 50 years.[b][18][19]

Coinage continued in small amounts until 1839, when official production of the Gobrecht dollar ceased.[20] The coins had been struck as a trial to gauge public acceptance.[21] The Mint acquired a portrait lathe in 1837, which allowed Gobrecht to work in large models for the later versions of the Gobrecht dollar, and for the Seated Liberty dollar. The lathe, a pantograph-like device, mechanically reduced the design from the model to a coin-size hub, from which working dies could be produced.[14] Prior to 1837, the engraver had to cut the design onto the die face by hand.[22]

Production

Design

Prior to full-scale production of a dollar coin in 1840, Patterson reviewed the designs then in use, including the Gobrecht dollar's.[21] The director opted to replace Gobrecht's soaring eagle reverse with a left-facing bald eagle based on a design by former Mint engraver John Reich,[21] a design first used on silver and gold coinage in 1807.[23] Although the reverse for the dollar was probably selected to match that of the quarter and half dollar, it is not known why the flying eagle design was not used for the lower denominations in the first place.[14] Numismatic historian Walter Breen speculates that a Treasury official might have preferred the Reich design.[24]

The obverse of the Gobrecht dollar was in high relief, but Mint officials felt that this should be lowered for the new coin, which was to be struck in much larger quantities. Patterson hired Robert Ball Hughes, a Philadelphia artist, to modify the design. As part of Hughes' modifications, Liberty's head was enlarged, the drapery was thickened, and the relief was lowered overall.[21] Thirteen stars were also included on the obverse.[25] On the Gobrecht dollar, with its high relief, the depiction of Liberty appears like a statue on a plinth; the flatter Seated Liberty decreased relief appears more like an engraving.[18]

Art historian Cornelius Vermeule tied the appearance of the obverse to neoclassicism, noting the resemblance of Gobrecht's Liberty to the marble statues of ancient Rome. The neoclassical school was popular in the first half of the 19th century, and not only among official artists; Vermeule noted, "it becomes almost painfully evident that similar sources were consulted both by the engravers of United States coins in Philadelphia and by the cutters of tombstones from Maine to Illinois".[26] The reverse retained the shield upon the eagle's breast. Art historian Vermeule described it as "the same old unnatural, unartistic eagle with shield on his stomach, like a baseball umpire's protector ... to clutch branch and olives in one foot, arrows of war in the other oversized set of claws".[18] According to numismatic historian David Lange, the Reich-Gobrecht reverse design is known among some coin collectors as the "sandwich-board eagle".[27] Breen, in his comprehensive volume on US coins, complains of "the 'improvements' inflicted by [Hughes] on a hapless Ms. Liberty. Compared with the original Sully-Gobrecht conception of 1836–39, this is a sorry mess indeed."[24]

Release

A small production run of 12,500 was minted in July 1840 to allow bullion depositors to become familiar with the new coins before having their silver struck into dollars.[28] The process of bringing the new coin to public hands was made easier by a congressional authorization in 1837 for a fund that allowed the Mint a "float", permitting it to give depositors payment in coin without waiting for their metal to go through the minting process.[27] Bullion producers began depositing the silver required to initiate heavier production later in 1840; 41,000 pieces were minted in November, followed by a mintage of 7,505 in December.[28] Deposits increased the following year, which saw a mintage of 173,000 pieces.[29] All coins were produced at the Philadelphia Mint until 1846, when 59,000 were struck at the Mint at New Orleans.[30]

Following the discovery of gold in California, a large amount of gold coins began appearing in American commercial channels.[31] The influx caused the price of gold relative to silver to decrease, making silver coins worth more as bullion than as currency.[24] They were exported abroad, or else melted locally for their bullion value.[31] As it was profitable to export silver, little was presented at the Mint, which resulted in low mintage numbers for the silver dollar; 1,300 and 1,100 were struck in 1851 and 1852 respectively.[30] The rarity of these dates was recognized by the late 1850s; Mint employees made surreptitious restrikes to sell to collectors.[24]

Congress passed the Coinage Act of 1853 in February of that year.[32] The act lowered the silver weight of the coins ranging from the half dime to half dollar by 6.9%, though the dollar remained unaffected.[32] The 1853 act eliminated the practice of depositing silver bullion to be struck into coin, except into the dollar for which a coining charge of .5% was imposed. According to the Senate report filed with the bill which became the Coinage Act, these changes were intended as a temporary expedient, with the free coinage of silver to be restored when bullion prices became stable.[33] Sources vary in their explanation as to why Congress chose to exempt the dollar from the silver coinage overhaul: numismatic historian R.W. Julian suggests that it was done due to its status as the "flagship" of American coins.[32] According to Don Taxay in his history of the Mint and coinage, "the silver dollar, which it [the act] left unchanged to preserve a bi-metallic currency, continued to be exported and was rarely used in commerce. Without realizing it, the country had entered onto the gold standard."[34] Julian agreed, noting that the act instituted a de facto gold standard in the United States, because it required silver coinage to be paid for in gold.[35] The silver dollar continued to circulate little; quantities were sent west beginning in 1854 to serve as "small change" in California.[24] Silver prices remained high into the 1860s, and little silver bullion was presented for striking into dollars. To serve collectors, individual specimens were made available to the public by the Mint at a cost of $1.08.[24]

Later years

Numismatist and coin dealer Q. David Bowers believes that most Seated Liberty dollars produced after 1853 were shipped to China to pay for luxury goods, including tea and silk.[36] R. W. Julian argued to the contrary, that continued production of the dollar had little to do with trade with the Orient (where goods were paid for in silver), suggesting instead that the coins were sent to the West for use there.[36] However, although the Mint's Engraving Department sent dies for the dollar to the San Francisco facility repeatedly from 1858 on, the California mint used them only once before 1870, striking 20,000 dollars in 1859, a year in which 255,700 were struck at Philadelphia and 360,000 at New Orleans. Production at New Orleans was disrupted after 1860 by the Civil War; it did not strike silver dollars again until 1879, after the end of the Seated Liberty series.[24][37][38] After the outbreak of the war in 1861, inflationary greenbacks were introduced, and precious-metal coins vanished from circulation.[39][40] In April 1863, new Mint Director James Pollock argued that the silver dollar be eliminated, noting in a letter that the coin "no longer enters into our monetary system. The few pieces made are for Asiatic and other foreign trade and are not seen in circulation."[39]

In November 1861, Reverend M. R. Watkinson suggested in a letter that some sort of religious motto should be placed on American coinage to reflect the increasing religiosity of United States citizens following the outbreak of the Civil War. In an October 21, 1863, report to Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase, Pollock expressed his own desire to emblazon American coins with a religious motto. The Mint began producing patterns bearing various mottoes, including "God Our Trust" and "In God We Trust"; the latter was ultimately selected, and its first use was on the two-cent piece in 1864.The following year, a law was passed allowing the Treasury to place the motto upon any coin at its discretion. The motto was placed on the silver dollar, as well as various other silver, gold and base metal coins, in 1866.[41]

The coin shortage continued after the end of the Civil War, due largely to the large war debt incurred by the federal government. As a result, silver coinage began to trade at a significant premium to the now ubiquitous greenbacks. Accordingly, the government was reluctant to issue silver coins. Nevertheless, the Mint continued striking silver, to be stored in vaults until such time as they could enter the marketplace.[42] The Seated Liberty dollar was the first coin to be struck at the Carson City Mint; the first to be issued were 2,303 pieces paid to a Mr. A. Wright on February 11, 1870.[43] The dollar was struck at Carson City from 1870 to 1873, with the largest mintage, 11,758, in 1870. The largest quantity struck at any mint was in 1872 at Philadelphia: 1,105,500, though the mintage in 1871 had also exceeded a million.[30]

Abolition and aftermath

Beginning in 1859, large quantities of silver were found in Nevada Territory and elsewhere in the American West.[44] In 1869, Director of the Mint Henry Linderman began advocating the end of the acceptance of silver bullion deposits to be struck into dollars. Although silver dollars were not coined in large numbers, Linderman saw that mining in the West would increase after the completion of the transcontinental railroad,[c] which it did, as US silver production increased from 10 million troy ounces in 1867 to more than 22 million five years later. Linderman foresaw that these activities would increase the supply of silver, causing its price to drop below the $1.2929 per ounce at which the precious metal in the standard silver dollar is worth $1.00. He anticipated that silver suppliers would turn to the Mint to dispose of their product by striking it into dollars. The monetization of that cheap silver, Linderman feared, would inflate the currency and drive gold from commerce because of Gresham's law. Although silver advocates later called the resulting law the "Crime of '73" and claimed that it had been passed in a deceitful manner, the bill was discussed during five different sessions of Congress, read in full by both the House of Representatives and the Senate and printed in full on multiple occasions. Once it passed both houses of Congress, it was signed into law by President Ulysses S. Grant on February 12, 1873.[45][46]

The Coinage Act of 1873 ended production of the standard silver dollar and authorized creation of the Trade dollar, thus concluding the Seated Liberty dollar series.[47] The Trade dollar was slightly heavier than the standard dollar and was intended for use in payments in silver to merchants in China. Although not meant for use in the United States, a last-minute rider gave it legal tender status there up to $5. When silver prices plummeted in the mid-1870s, millions appeared in circulation, at first in the West and then throughout the United States, causing problems in commerce when banks insisted on the $5 legal tender limit. Other abuses followed, such as purchase by companies for bullion value (by then about $0.80) for use in pay packets. Workers had little option but to accept them as dollars. In response to complaints, Congress ended any status as legal tender in 1876, halted production of the Trade dollar (except for collectors) in 1878, and agreed to redeem any which had not been chopmarked in 1887.[48]

The 1873 act eliminated the provisions allowing depositors of silver bullion to have their metal struck into standard silver dollars; they could now only receive Trade dollars, which were not legal tender beyond $5.[49][50] As the price of silver then was about $1.30 per ounce, there was no outcry from silver producers.[51] Beginning in 1874, however, the price dropped; silver would not again sell for $1.2929 or more on the open market in the United States until 1963.[52] Advocates of silver both sought a market for the commodity and believed that "free silver" or bimetallism would boost the economy and make it easy for farmers to repay debts. Many in Congress agreed, and the first battle over the issue resulted in a partial victory for silver forces, as the 1878 Bland–Allison Act required the Mint to purchase large quantities of silver on the open market and strike the bullion into dollar coins. The Mint did so, using a new design by Assistant Engraver George T. Morgan,[d] which came to be known as the Morgan dollar.[53][54] The issue of what monetary standard would be used occupied the nation for the rest of the 19th century, becoming most acute in the 1896 presidential election. In that election, the unsuccessful Democratic candidate, William Jennings Bryan, campaigned on "free silver", having electrified the Democratic National Convention with his Cross of Gold speech, decrying the gold standard. The issue was settled for the time by the Gold Standard Act of 1900, making that standard the law of the land.[53][55]

Collecting

Considerable private melting in the early years of the series makes many dates rare; more melting took place when large quantities that had accumulated at the New York Sub-Treasury were sent to Philadelphia in 1861 and 1862 for restriking into smaller denominations.[56] R. S. Yeoman's 2014 edition of A Guide Book of United States Coins[e] lists no Seated Liberty dollar in collectable condition (very good or better) at less than $280.[57]

The key dates of the series include the 1866 variety which lacks the motto "In God We Trust", of which only two are known; one sold at auction in 2005 for $1,207,500.[58] Another rarity is the 1870 struck at San Francisco (1870-S), of which the mintage is not known as their striking was not recorded in that mint's records. Those records indicate that in May 1870, the San Francisco Mint returned two dollar reverse dies to Philadelphia as mistakenly sent without mint mark, and received two proper replacements. There is no record of any 1870-dated obverse dies for the dollar being sent to San Francisco; nevertheless, the coins exist. Breen, writing in 1988, lists twelve examples known, which he speculates may have been presentation pieces, meant to be inserted in a cornerstone.[59] One sold at auction for $1,092,500 in 2003.[58] A similar mystery attends the 1873-S, which despite the stated mintage of 700, is not known to exist. Two of the pieces were routinely sent to Philadelphia for examination at the 1874 meeting of the United States Assay Commission, but apparently were not preserved. Breen suggests that the remaining mintage may have been melted along with obsolete silver coins.[60]

Notes

References

- ^ a b Coin World Almanac 1977, p. 247.

- ^ Lange, p. 37.

- ^ a b Julian, p. 431.

- ^ Taxay, pp. 125–126.

- ^ a b Julian, p. 495.

- ^ Lange, p. 41.

- ^ Taxay, pp. 145, 149.

- ^ Lange, pp. 41–43.

- ^ Coin World Almanac 1977, pp. 200–202.

- ^ Yeoman, p. 222.

- ^ a b c d e Julian, p. 496.

- ^ a b Taxay, p. 171.

- ^ Coin World Almanac 1977, p. 211.

- ^ a b c Lange, p. 46.

- ^ a b Julian, p. 498.

- ^ a b Julian, p. 504.

- ^ Peters, pp. 246–251.

- ^ a b c Vermeule, p. 47.

- ^ Yeoman, pp. 139–142, 147–151, 163–167, 195–200.

- ^ Julian, p. 505.

- ^ a b c d Julian, p. 535.

- ^ Taxay, p. 150.

- ^ Yeoman, pp. 185, 234.

- ^ a b c d e f g Breen, p. 436.

- ^ Yeoman, p. 217.

- ^ Vermeule, pp. 47–48.

- ^ a b Lange, p. 47.

- ^ a b Julian, p. 537.

- ^ Yeoman, p. 214.

- ^ a b c Yeoman, p. 218.

- ^ a b Julian, p. 538.

- ^ a b c Julian, p. 539.

- ^ Taxay, pp. 219–224.

- ^ Taxay, p. 221.

- ^ Julian, p. 540.

- ^ a b Julian, p. 542.

- ^ Yeoman, pp. 218–222.

- ^ Coin World Almanac 1977, p. 203.

- ^ a b Julian, p. 544.

- ^ Coin World Almanac 1977, pp. 321–325.

- ^ Julian, p. 546.

- ^ Julian, p. 547.

- ^ Lange, p. 111.

- ^ Coin World Almanac 1977, p. 165.

- ^ Van Allen & Mallis, pp. 21–23.

- ^ Taxay, pp. 259–261.

- ^ Van Allen & Mallis, p. 23.

- ^ Breen, p. 466.

- ^ Breen, pp. 441–443.

- ^ Taxay, p. 259.

- ^ Coin World Almanac 1977, p. 153.

- ^ Coin World Almanac 1977, pp. 167, 179–180.

- ^ a b Lange, pp. 119–122.

- ^ Taxay, pp. 267–271.

- ^ Breen, p. 443.

- ^ Breen, pp. 436–443.

- ^ Yeoman, pp. 222–223.

- ^ a b Yeoman, p. 223.

- ^ Breen, p. 442.

- ^ Breen, pp. 440–441.

Bibliography

- Breen, Walter (1988). Walter Breen's Complete Encyclopedia of U.S. and Colonial Coins. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-14207-6.

- Coin World Almanac (3rd ed.). Sidney, Ohio: Amos Press. 1977. OCLC 4017981.

- Julian, R.W. (1993). Bowers, Q. David (ed.). Silver Dollars & Trade Dollars of the United States. Wolfeboro, New Hampshire: Bowers and Merena Galleries. ISBN 0-943161-48-7.

- Lange, David W. (2006). History of the United States Mint and its Coinage. Atlanta, Ga.: Whitman Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7948-1972-9.

- Peters, Richard, ed. (1845). The Public Statutes at Large of the United States of America. Boston, Mass.: Charles C. Little and James Brown.

- Taxay, Don (1983). The U.S. Mint and Coinage (reprint of 1966 ed.). New York: Sanford J. Durst Numismatic Publications. ISBN 978-0-915262-68-7.

- Van Allen, Leroy C.; Mallis, A. George (1991). Comprehensive Catalog and Encyclopedia of Morgan & Peace Dollars. Virginia Beach, Va.: DLRC Press. ISBN 978-1-880731-11-6.

- Vermeule, Cornelius (1971). Numismatic Art in America. Cambridge, Mass.: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-62840-3.

- Yeoman, R.S. (2013). A Guide Book of United States Coins (The Official Red Book) (67th ed.). Atlanta, Ga.: Whitman Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7948-4180-5.