Sean

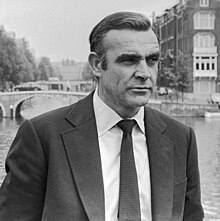

The popularity of actor Sean Connery increased use of the name in the Anglosphere. | |

| Pronunciation | English: /ˈʃɔːn/ SHAWN Irish: [ʃaːn̪ˠ, ʃeːn̪ˠ] |

|---|---|

| Gender | Male |

| Language(s) | Irish language |

| Other gender | |

| Feminine | Shawna, Shauna, Seána, Shona, Seanna, Siobhán, Sinéad |

| Origin | |

| Region of origin | Irish cognate of John (Hebrew origin) |

| Other names | |

| Variant form(s) | Seaghán, Seón, Shaun, Shawn, Seann, Seaghán, Seathan, Shaine, Shayne, Shane, Shon, Shan |

| Related names | Eoin, John |

Sean, also spelled Seán or Séan in Hiberno-English,[1][2] is a male given name of Irish origin. It comes from the Irish versions of the Biblical Hebrew name Yohanan (יוֹחָנָן), Seán (anglicized as Shaun/Shawn/Shon) and Séan (Ulster variant;[3] anglicized Shane/Shayne), rendered John in English and Johannes/Johann/Johan in other Germanic languages. The Norman French Jehan (see Jean) is another version.

In the Irish language, the presence and placement of the síneadh fada is significant, as it changes the meaning of the name.[1] The word "Sean" in Irish means "old", while the word "Séan" means "omen".[4]

For notable people named Sean, refer to List of people named Sean.

Origin

The name was adopted into the Irish language most likely from Jean, the French variant of the Hebrew name Yohanan. As Irish has no letter ⟨j⟩ (derived from ⟨i⟩; English also lacked ⟨j⟩ until the late 17th Century, with John previously been spelt Iohn) so it is substituted by ⟨s⟩, as was the normal Gaelic practice for adapting Biblical names that contain ⟨j⟩ in other languages (Sine/Siobhàn for Joan/Jane/Anne/Anna; Seonaid/Sinéad for Janet; Seumas/Séamus for James; Seosamh/Seòsaidh for Joseph, etc.). In 1066, the Norman duke, William the Conqueror conquered England, where the Norman French name Jahan/Johan (Old French: [dʒəˈãn], Middle English: [dʒɛˈan])[citation needed] came to be pronounced Jean,[clarification needed] and spelled John. The Norman from the Welsh Marches, with the Norman King of England's mandate invaded parts of Leinster and Munster in the 1170s. The Irish nobility in these areas were replaced by Norman nobles, some of whom bore the Norman French name Johan or the anglicised name John. The Irish adapted the name to their own pronunciation and spelling, producing the name Seán (or Seathan). Sean is commonly pronounced /ʃɔːn/ (Irish: Seán [ʃaːn̪ˠ]; (Ulster dialect: [ʃæːn̪ˠ]) or /ʃeɪn/ (Irish: Séan [ʃeːn̪ˠ], with síneadh fada on ⟨e⟩, not ⟨a⟩,[citation needed] thus leading to the variant Shane.)

The name was once the common equivalent of John in Ireland and Gaelic-speaking areas of Scotland, but has been supplanted by a vulgarization of its address form: Iain or Ian.[5] When addressing someone named Seán in Irish, it becomes a Sheáin [ə ˈçaːnʲ], and in Scotland was generally adapted into Scots and Highland English as Eathain, Eoin, Iain, and Ian (John has traditionally been more commonly used in the Scots-speaking Lowlands than any form of Seán). Even in Highland areas where Gaelic is still spoken, these anglicisations are now more common than Seán or Seathan, undoubtedly due in part to registrars in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland having long been instructed not to register Irish or Gaelic names in birth or baptismal registrations.[6]

North American usage

Some Irish bearers of the name, such as playwright Sean O'Casey and writer Seán Ó Faoláin, were originally named John but changed their names to demonstrate support for Ireland's independence. The name Sean was used by the 1920s for children born in the United States and became more widely used by the early 1940s. Along with spelling variants Shawn and Shaun, the name was among the top 1,000 names for American boys by 1950 and, with all spellings combined, was a top 10 name for American boys in 1971. The popularity of actor Sean Connery increased use of the name. The name Shaun was popularized in the late 1970s by singer Shaun Cassidy. It has since declined in use but, with all spellings combined, remained among the 300 most popular names for newborn American boys in 2022. The name is also in use for girls in the United States and Canada, with Shawn the most widely used spelling, perhaps due to its similarity to the name Dawn. Shawn was among the top 1,000 names for American girls between 1948 and 1988 and was at peak popularity as a name for girls there in 1970.[7] [8]

In other languages

- English: Sean, Seon, Shane, Shayne, Shaine, Shon, Shaun, Shawn, Seann, Shaan

- Welsh: Sion, Shôn

- Scottish Gaelic, Highland English and Scots: Eathain, Eoin, Iain, Ian

- Korean: 션, 숀, 셔은, 쇼은

- Japanese: ショーン

- Chinese: 肖恩, 尚恩

- Arabic: شان

- Hebrew: שון

See also

References

- ^ a b Caollaí, Éanna Ó. "If your name is Timothy or Pat you're grand, but if it's Seán or Róisín you don't exist". The Irish Times. Retrieved 5 May 2022.

- ^ Ó Séaghdha, Darach (3 March 2022). "The Irish For: The rise of Rían - the latest baby names in Ireland". thejournal.ie. The Journal. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- ^ "Meaning of Sean - What does the Name Sean mean?". Babynamesocean.com. Retrieved 2011-12-06.

- ^ "Foclóir Gaeilge–Béarla (Ó Dónaill): séan". Teanglann. Teanglann.ie. Retrieved 26 March 2024.

- ^ Dwelly, Edward (1994). Faclair Gaidhlig Gu Beurla Le Dealbhan; Dwelly's Illustrated Gaelic to English Dictionary. Glasgow, Scotland: Gairm Gaelic Publications, 29 Waterloo Street, Glasgow. ISBN 1871901286.

- ^ "The Prohibition of Gaelic Names". www.auchindrain.org.uk. Auchindrain Township, Auchindrain, Inveraray, Argyll, PA32, 8WD. 2021. Retrieved 2021-07-23.

The practice of the law and official systems refusing to recognise the existence of Gaelic went back two centuries. It was rooted in a view that Gaelic was a barbaric language, and that if the Gaels were to become civilised they had to learn and use English instead. We don't yet know exactly when the law was changed to allow Gaelic names, but it was certainly well into the 1960s, possibly even later.

- ^ Evans, Cleveland Kent (26 February 2024). "Cleveland Evans: Sean Has Roots in Irish Ancestry". omaha.com. Omaha World Herald. Retrieved 27 February 2024.

- ^ Hanks, Patrick; Hardcastle, Kate; Hodges, Flavia (2006). Oxford Dictionary of First Names. Oxford University Press. p. 60. ISBN 0-19-861060-2.