Scientific-Humanitarian Committee

The Scientific-Humanitarian Committee (German: Wissenschaftlich-humanitäres Komitee, WhK) was founded by Magnus Hirschfeld in Berlin in May 1897, to campaign for social recognition of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people, and against their legal persecution.[1][2][3] It was the first LGBT rights organization in history.[3][4][5] The motto of the organization was "Per scientiam ad justitiam" ("through science to justice"), and the committee included representatives from various professions.[4][2] The committee's membership peaked at about 700 people.[4] In 1929, Kurt Hiller took over as chairman of the group from Hirschfeld. At its peak, the WhK had branches in approximately 25 cities in Germany, Austria and the Netherlands.

History

The WhK was founded in Berlin-Charlottenburg, a locality of Berlin, on 14 or 15 May 1897 (about four days before Oscar Wilde's release from prison) by Magnus Hirschfeld, a physician, sexologist and outspoken advocate for gender and sexual minorities. Original members of the WhK included Hirschfeld, publisher Max Spohr, lawyer Eduard Oberg and writer Franz Joseph von Bülow.[6][4] Adolf Brand, Benedict Friedländer, Hermann von Teschenberg and Kurt Hiller also joined the organization. A split in the organization occurred in December 1906, led by Friedländer.[7]

The committee was based in the Institute for Sexual Sciences in Berlin until the institute's destruction at the hands of Nazis in 1933. The WhK was affiliated with the World League for Sexual Reform, another group founded by Hirschfeld which had similar aims to the committee.[9] The committee had ties to gay organizations across the world, and from 1906 onward the body which crafted the committee's policy was made up of members from several European countries.[10][11] A branch in Vienna, Austria was opened in 1906, led by Joseph Nicoladoni and Wilhelm Stekel.[10] In 1911, the Dutch branch of the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee was formed by Jacob Schorer.[12]

The WhK took a great deal of scientific theories on human sexuality from the institute such as the idea of a third sex between a man and a woman. The initial focus of the committee was to repeal Paragraph 175, an anti-gay piece of legislation of the Imperial Penal Code, which criminalized "coitus-like" acts between males. It also sought to demonstrate the innateness of homosexuality and thus make the criminal law against sodomy in Germany at the time inapplicable.

In campaigning against Paragraph 175, the committee argued that homosexuality was not a disease or moral failing, and said they reached this conclusion from scientific evidence. The group made other arguments against this law, saying for example that its repeal would reduce blackmailing behavior among male prostitutes.[13] Beginning in 1919 and 1920, the WhK allied with other homosexual rights groups including the Gemeinschaft der Eigenen (Community of the Special) and Deutscher Freundschaftsverband (German Friendship Association) to oppose the law.[14] Another alliance held by the committee in its activism against Paragraph 175 was with the Deutscher Bund für Mutterschutz (German League for the Protection of Motherhood), especially after proponents of Paragraph 175 proposed extending it to women.[15][4]

The committee created sex-education pamphlets on the topic of homosexuality and distributed them to the public.[4] It had begun distributing this type of material to university students and factory laborers as early as 1903.[12] They also assisted defendants in criminal trials, and gathered more than 6,000 signatures on a petition for the repeal of Paragraph 175.[16][17] The committee's opposition was not indiscriminate, as its petition did support preservation of criminal status for some homosexual acts, including cases between an adult and a minor under age 16.[15][18] At the time of the original proposal, the age of consent was in fact two years lower than that for heterosexual people, at age 14; effectively they called for the age of consent to be raised as part of their campaign.[18]

Work on promoting their petition began in 1897, and the committee particularly wanted signatures from those with prominent status in such fields as politics, medicine, art, and science. They sent thousands of letters to key figures such as Catholic priests, judges, lawmakers, journalists, and mayors. August Bebel signed the petition and took copies to the Reichstag to urge colleagues to add their names. Other signatories included Albert Einstein, Hermann Hesse, Thomas Mann, Rainer Maria Rilke, and Leo Tolstoy.[3]

During World War I, supporters and members went to fight in the war. Some of its publications were affected by censorship during this time period. The petition campaign largely fell by the wayside until the war was over. Hirschfeld focused on showcasing the experiences of homosexual soldiers; he collected thousands of letters, interviews, and surveys with such soldiers.[15][19] Petitions were submitted in 1898, 1922, and 1925, but failed to gain the support of the parliament. The law continued to criminalize homosexuality until 1969 and was not entirely removed in West Germany until four years after East and West Germany became one country in 1994.

Officially, the committee was non-partisan politically, and made efforts to appeal to parliamentarians from many parties. This sometimes even included conservative parties such as the Bavarian People's Party (BVP). However, Hirschfeld was a member of the Social Democratic Party (SPD). Some other leaders in the group had revolutionary or pacifist sympathies.[14] While the committee was somewhat informally associated with the SPD, they were also alienated by the SPD's rhetorical exploitation of Ernst Röhm's homosexuality as a means to harm the Nazi Party politically. After seeing these attacks against Röhm in a newspaper aligned with the SPD, the committee responded, "The statements in the Münchner Post, hearkening back to the Apostle Paul and employing the entire vocabulary of our conservative-clerical persecutors, could have been printed without changing a word by the most strictly Catholic press." This conflict of interests caused the committee to privately question the executive of the SPD as to whether they were still in favor of repealing Paragraph 175; the SPD affirmed that was still their position.[20]

The biological deterministic tendency that Hirschfeld gave to the committee met with opposition within the WhK from the start. But it was not until November 24, 1929 that his internal competitors, above all the Communist Party (KPD) functionary Richard Linsert, succeeded in forcing Hirschfeld to resign. He was succeeded by the Medical Councilor Otto Juliusburger, Kurt Hiller was elected Deputy Chairman and the writer Bruno Vogel became the third member of the new board. Juliusburger led the committee in the short time that elapsed until the committee was dissolved after the Nazi Party came to power in 1933.[21] The committee's final meeting took place in Peter Limann's apartment on June 8, 1933, with the singular purpose of dissolving the organization.[22] A reorientation of the WhK that freed it from its scientific isolation was the focus placed on psychological and sociological research instead of biological research.

The committee was based in Berlin and had branches in about 25 German, Austrian and Dutch cities. It had roughly 700 members at its peak and is considered an important milestone in the homosexual emancipation movement.[23] It existed for thirty-six years.[15]

Publications

The WhK produced the Jahrbuch für sexuelle Zwischenstufen (Yearbook for Intermediate Sexual Types), a publication which reported the committee's activities and contained content ranging from articles about homosexuality among "primitive" people to literary analyses and case studies. It was published regularly from 1899 to 1923 (sometimes quarterly) and more sporadically until 1933. Yearbook was the world's first scientific journal dealing with sexual variants.[24][25]

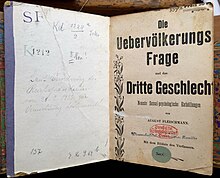

Another of the WhK's widespread publications was a brochure entitled Was soll das Volk vom dritten Geschlecht wissen? (What Must Our Nation Know about the Third Sex?) that was produced alongside the committee's sexual education lectures. It offered information on homosexuality, pulling largely from the studies of the Institute for Sexual Sciences. The brochure offered a rare case of nonjudgmental insight into the existence of homosexuality and, as such, was frequently distributed by homosexuals to family members or to total strangers on public transport.[23]

Reformation attempts

In October 1949, Hans Giese joined with Hermann Weber (1882–1955), head of the Frankfurt local group from 1921 to 1933, to re-establish the group in Kronberg. Kurt Hiller worked with them briefly, but stopped due to personal differences after a few months. The group was dissolved in late 1949 or early 1950 and instead formed the Committee for Reform of the Sexual Criminal Laws (Gesellschaft für Reform des Sexualstrafrechts e. V.), which existed until 1960.[26][27]

In 1962 in Hamburg, Kurt Hiller, who had survived Nazi concentration camps and continued to fight against anti-gay repression, tried unsuccessfully to re-establish the WhK.[28][29]

New WhK

In 1998, a new group was formed with the same name.[30] Growing out of a group against politician Volker Beck in that year's election,[31] it is similar in name and general subject matter only, and takes more radical positions than the conservative LSVD. In 2001, its magazine Gigi was given a special award by the German Association of Lesbian and Gay Journalists.

See also

References

- ^ Crocq, Marc-Antoine (2021-01-01). "How gender dysphoria and incongruence became medical diagnoses – a historical review". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 23 (1): 44–51. doi:10.1080/19585969.2022.2042166. PMC 9286744. PMID 35860172. S2CID 249301944.

- ^ a b Leng, Kirsten (1 March 2017). "Magnus Hirschfeld's Meanings: Analysing Biography and the Politics of Representation". German History. 35 (1). Oxford University Press: 96–116. doi:10.1093/gerhis/ghw142.

- ^ a b c Peters, Steve (February 18, 2019). "LGBT History Month 2019 Faces – Magnus Hirschfeld and the first LGBT+ film". Canterbury Christ Church University. Retrieved May 14, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Dose, Ralf (2014-04-11). Magnus Hirschfeld: The Origins of the Gay Liberation Movement. New York University Press. pp. 38–51. ISBN 978-1-58367-438-3.

- ^ Djajic-Horváth, Aleksandra (10 May 2022). "Magnus Hirschfeld". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 10 June 2022.

In 1897 Hirschfeld established the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee with Max Spohr, Franz Josef von Bülow, and Eduard Oberg; it was the world's first gay rights organization.

- ^ "Magnus Hirschfeld and HKW". Haus der Kulturen der Welt. 21 June 2019.

In 1897, together with Max Spohr, Eduard Oberg and Franz Joseph von Bülow, he founded the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee in Berlin Charlottenburg.

- ^ Beachy, Robert (October 2015). Gay Berlin: Birthplace of a Modern Identity. Knopf. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-307-47313-4.

- ^ "Dinge, die wir suchen". magnus-hirschfeld.de. Retrieved 2016-08-07.

- ^ Dose, Ralf; Selwyn, Pamela Eve (January 2003). "The World League for Sexual Reform: Some possible approaches". Journal of the History of Sexuality. 12 (1). University of Texas Press: 1–15. doi:10.1353/sex.2003.0057. S2CID 142887092 – via Project MUSE.

Other corporate members were the Scientific Humanitarian Committee...

- ^ a b Dynes, Wayne R. (2016-03-22). Encyclopedia of Homosexuality: Volume I. Routledge. pp. 234, 279. ISBN 978-1-317-36815-1. Archived from the original on 11 June 2022.

- ^ Belmonte, Laura A. (2020-12-10). The International LGBT Rights Movement: A History. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 63–64. ISBN 978-1-4725-0695-5.

- ^ a b Plant, Richard (2013). The Pink Triangle: the Nazi War Against Homosexuals. New York: Henry Holt and Company. pp. 22, 62. ISBN 978-1-4299-3693-4. OCLC 872608428.

- ^ Sengoopta, Chandak (1998). "Glandular Politics: Experimental Biology, Clinical Medicine, and Homosexual Emancipation in Fin-de-Siecle Central Europe". Isis. 89 (3): 445–473. doi:10.1086/384073. ISSN 0021-1753. JSTOR 237142. PMID 9798339. S2CID 19788523.

- ^ a b Tamagne, Florence (2007). A History of Homosexuality in Europe, Vol. I & II: Berlin, London, Paris 1919-1939. Algora Publishing. pp. 65–68. ISBN 978-0-87586-357-3.

- ^ a b c d Dynes, Wayne R. (2016-03-22). Encyclopedia of Homosexuality: Volume II. Routledge. pp. 1168–1170. ISBN 978-1-317-36812-0.

- ^ Ramsey, Glenn (2008). "The Rites of Artgenossen : Contesting Homosexual Political Culture in Weimar Germany". Journal of the History of Sexuality. 17 (1): 85–109. doi:10.1353/sex.2008.0009. ISSN 1535-3605. PMID 19260158. S2CID 22292105.

- ^ "Henry Gerber: Ahead of his time". The Washington Blade. October 3, 2013. Retrieved May 13, 2021.

...Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld founded the gay organization Wissenschaftlich-humanitäres Komitee (Scientific-Humanitarian Committee). Its first action was to draft a petition against Paragraph 175 with 6,000 signatures of prominent people in the arts, politics and the medical profession; it failed to have any effect.

- ^ a b Janssen, Diederik F. (2018). "Uranismus complicatus: Scientific-Humanitarian Disentanglements of Gender and Age Attractions". Journal of the History of Sexuality. 27 (1): 115–117. doi:10.7560/JHS27104. ISSN 1043-4070. JSTOR 44862431. S2CID 148966028.

- ^ Crouthamel, Jason (October 2011). "Cross-dressing for the fatherland: sexual humour, masculinity and German soldiers in the First World War". First World War Studies. 2 (2): 195–215. doi:10.1080/19475020.2011.613240. ISSN 1947-5020. S2CID 145307131.

- ^ Oosterhuis, Harry (1995-11-27). "The "Jews" of the Antifascist Left: Homosexuality and the Socialist Resistance to Nazism". Journal of Homosexuality. 29 (2–3): 227–257. doi:10.1300/J082v29n02_09. ISSN 0091-8369. PMID 8666756.

- ^ Herzer, Manfred (2017-10-09). Magnus Hirschfeld und seine Zeit. doi:10.1515/9783110548426. ISBN 9783110548426.

- ^ Hekma, Gert; Oosterhuis, Harry; Steakley, James; Steakley, James D. (1995). Gay Men and the Sexual History of the Political Left. Haworth Press. p. 217. ISBN 978-1-56024-724-1.

- ^ a b Dose, Ralf (2014). Magnus Hirschfeld and the origins of the gay liberation movement. New York. p. 42. ISBN 978-1-58367-439-0. OCLC 870272914.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Hirschfeld, Magnus (1868-1935)". GLBTQ Encyclopedia Project. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- ^ John Lauritsen; David Thorstad (1974), The Early Homosexual Rights Movement (1864–1935), New York: Times Change Press, ISBN 0-87810-027-X. Revised edition published 1995, ISBN 0-87810-041-5.

- ^ Bernd-Ulrich Hergemöller [in German] (2001), Mann für Mann. Ein biographisches Lexikon, Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp-Taschenbuch-Verlag, 2001, ISBN 3-518-39766-4, ISBN 3-928983-65-2. Entries for Hans Giese p. 278, and Kurt Hiller p. 357: Citation.

- ^ Jürgen Müller, Review of: Andreas Pretzel (Ed.): NS-Opfer unter Vorbehalt. - Homosexuelle Männer in Berlin nach 1945, LIT-Verlag, Münster 2002

- ^ Online exhibition of the Magnus Hirschfeld Society: Kurt Hiller

- ^ Kennedy, Hubert. "Hiller, Kurt (1885-1972)" (PDF). GLBTQ Encyclopedia Project. Retrieved 10 June 2022.

- ^ whk - wissenschaftlich-humanitäres komitee

- ^ The history of the new WHK (german)

Further reading

- Friedländer, Benedict (1907). Memoir for the Friends and Contributors of the Scientific Humanitarian Committee in the Name of the Secession of the Scientific Humanitarian Committee. Journal of Homosexuality. 22 (1): 71–84. doi:10.1300/J082v22n01_06

External links

Media related to Scientific-Humanitarian Committee at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Scientific-Humanitarian Committee at Wikimedia Commons