Scandinavian hunter-gatherer

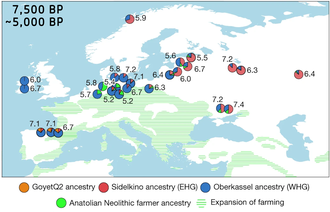

In archaeogenetics, the term Scandinavian hunter-gatherer (SHG) is the name given to a distinct ancestral component that represents descent from Mesolithic hunter-gatherers of Scandinavia.[a][3][4] Genetic studies suggest that the SHGs were a mix of western hunter-gatherers (WHGs) initially populating Scandinavia from the south during the Holocene, and eastern hunter-gatherers (EHGs), who later entered Scandinavia from the north along the Norwegian coast. During the Neolithic, they admixed further with Early European Farmers (EEFs) and Western Steppe Herders (WSHs). Genetic continuity has been detected between the SHGs and members of the Pitted Ware culture (PWC), and to a certain degree, between SHGs and modern northern Europeans.[b] The Sámi, on the other hand, have been found to be completely unrelated to the PWC.[c]

Research

Scandinavian hunter-gatherers (SHG) were identified as a distinct ancestral component by Lazaridis et al. (2014). A number of remains examined at Motala, Sweden, and a separate group of remains from 5,000 year-old hunter-gatherers of the Pitted Ware culture (PWC), were identified as belonging to SHG. The study found that an SHG individual from Motala ('Motala12') could be successfully modelled as being of c. 81% western hunter-gatherer (WHG) ancestry, and c. 19% Ancient North Eurasian (ANE) ancestry.[7]

Haak et al. (2015) examined the remains of six SHGs buried at Motala between ca. 6000 BC and 5700 BC. Of the four males surveyed, three carried the paternal haplogroup I2a1 or various subclades of it, while the other carried I2c. With regard to mtDNA, four individuals carried subclades of U5a, while two carried U2e1. The study found SHGs to constitute one of the three main hunter-gatherer populations of Europe during the Mesolithic.[d][e] The two other groups were WHGs and eastern hunter-gatherers (EHG). EHGs were found to be an ANE-derived population with significant admixture from a WHG-like source. SHGs formed a distinct cluster between WHG and EHG, and the admixture model proposed by Lazaridis et al. could be successfully replaced with a model that takes EHG as source population for the ANE-like ancestry, with an admixture ratio of ~65% (WHG) : ~35% (EHG).[9] SHGs living between 6000 BC and 3000 BC were found to largely be genetically homogeneous, with little admixture occurring among them during this period. EHGs were found to be more closely related to SHGs than WHGs.[8]

Mathieson et al. (2015) subjected the six SHGs from Motala to further analysis. SHGs appeared to have persisted in Scandinavia until after 5,000 years ago. The Motala SHGs were found to be closely related to WHGs.[10]

Lazaridis et al. (2016) confirmed SHGs to be a mix of EHGs (~43%) and WHGs (~57%). WHGs were modeled as descendants of the Upper Paleolithic people (Cro-Magnon) of the Grotte du Bichon in Switzerland with minor additional EHG admixture (~7%). EHGs derived c. 75% of their ancestry from ANEs.[f]

Günther et al. (2018) examined the remains of seven SHGs. All three samples of Y-DNA extracted belonged to subclades of I2. With respects to mtDNA, four samples belonged to U5a1 haplotypes, while three samples belonged U4a2 haplotypes. All samples from western and northern Scandinavia carried U5a1 haplotypes, while all the samples from eastern Scandinavia except from one carried U4a2 haplotypes. The authors of the study suggested that SHGs were descended from a WHG population that had entered Scandinavia from the south, and an EHG population which had entered Scandinavia from the northeast along the coast. The WHGs who entered Scandinavia are believed to have belonged to the Ahrensburg culture. These WHGs and EHGs had subsequently mixed, and the SHGs gradually developed their distinct character. The SHGs from western and northern Scandinavia had more EHG ancestry (c. 49%) than individuals from eastern Scandinavia (c. 38%). The SHGs were found to have a genetic adaptation to high latitude environments, including high frequencies of low pigmentation variants and genes designed for adaptation to the cold and physical performance. SHGs displayed a high frequency of the depigmentation alleles SLC45A2 and SLC24A5, and the OCA/Herc2, which affects eye pigmentation. These genes were much less common among WHGs and EHGs. A surprising continuity was displayed between SHGs and modern populations of Northern Europe in certain respects. Most notably, the presence of the protein TMEM131 among SHGs and modern Northern Europeans was detected. This protein may be involved in long-term adaptation to the cold.[5]

In a genetic study published in Nature Communications in January 2018, the remains of an SHG female at Motala, Sweden between 5750 BC and 5650 BC was analyzed. She was found to be carrying U5a2d and "substantial ANE ancestry". The study found that Mesolithic hunter-gatherers of the eastern Baltic also carried high frequencies of the HERC2 allele, and increased frequencies of the SLC45A2 and SLC24A5 alleles. They however harbored less EHG ancestry than SHGs. Genetic continuity between the SHGs and the Pitted Ware culture of the Neolithic was detected. The results further underpinned previous suggestion that SHGs were descended from northward migration of WHGs and a subsequent southward migration of EHGs.[12] A certain degree of continuity between SHGs and northern Europeans was detected.[b]

A study published in Nature in February 2018 included an analysis of a large number of individuals of prehistoric Eastern Europe. Thirty-seven samples were collected from Mesolithic and Neolithic Ukraine (9500–6000 BC). These were determined to be an intermediate between EHG and SHG. Samples of Y-DNA extracted from these individuals belonged exclusively to R haplotypes (particularly subclades of R1b1 and R1a)) and I haplotypes (particularly subclades of I2). mtDNA belonged almost exclusively to U (particularly subclades of U5 and U4).[13]

Physical appearance

According to Mathieson et al. (2015), 50% of Scandinavian Hunter Gatherers from Motala carried the derived variant of EDAR-V370A. This variant is typical of modern East Asian populations, and is known to affect dental morphology[16] and hair texture, and also chin protrusion and ear morphology,[17] as well as other facial features.[18] The authors did not detect East Asian ancestry in the Scandinavian Hunter Gatherers, and speculated that this gene might not have originated in East Asia, as is commonly believed.[19] However, more recent research incorporating ancient Northeast Asian samples has confirmed that EDAR-V370A originated in Northeast Asia, and spread to West Eurasian populations such as Motala in the Holocene period.[20] Mathieson et al. (2015) also reported: "A second surprise is that, unlike closely related western hunter-gatherers, the Motala samples have predominantly derived pigmentation alleles at SLC45A2 and SLC24A5."[19]

The study by Günther et al. (2018) further discovered that SHGs "show a combination of eye color varying from blue to light brown and light skin pigmentation. This is strikingly different from the WHGs—who have been suggested to have the specific combination of blue eyes and dark skin and EHGs—who have been suggested to be brown-eyed and light-skinned".

Four SHGs from the study yielded diverse eye and hair pigmentation predictions: one individual (SF12) was predicted to be most likely to have had dark hair and blue eyes; a second individual (Hum2) most likely had dark hair and brown eyes; a third (SF9) was predicted to have had light hair and brown eyes; and a fourth individual (SBj) was predicted to have had light hair, with the most likely hair colour being blonde, and blue eyes.

Of the SHGs from Motala, four were probably dark-haired, and two others were probably light-haired, and may have been blond. In addition, all of the six SHGs from Motala had high probabilities of being blue-eyed.

Both light and dark skin pigmentation alleles are found at intermediate frequencies in the Scandinavian Hunter Gatherers sampled, but only one individual had exclusively light-skin variants of two different SNPs.

The study found that depigmentation variants of genes for light skin pigmentation (SLC24A5, SLC45A2) and blue eye pigmentation (OCA2/HERC2) are found at high frequency in SHGs relative to WHGs and EHGs, which the study suggests cannot be explained simply as a result of the admixture of WHGs and EHGs. The study argues that these allele frequencies must have continued to increase in SHGs after admixture, which was probably caused by environmental adaptation to high latitudes.[21]

On the basis of archaeological and genetic evidence, the Swedish archaeologist Oscar D. Nilsson has made forensic reconstructions of both male and female SHGs.[22][23][24]

See also

Notes

- ^ "Earlier aDNA studies suggest the presence of three genetic groups in early postglacial Europe: Western hunter–gatherers (WHG), Eastern hunter–gatherers (EHG), and Scandinavian hunter–gatherers (SHG)4. The SHG have been modelled as a mixture of WHG and EHG."[2]

- ^ a b "Modern-day northern Europeans trace limited amounts of genetic material back to the SHGs."[5]

- ^ "Population continuity between the PWC and modern Saami can be rejected under all assumed ancestral population size combinations."[6]

- ^ "We can discern three different groups of hunter-gatherers who lived in Europe before the arrival of the first farmers: western European hunter-gatherers (WHG) in Spain, Luxembourg, and Hungary; eastern European hunter-gatherers (EHG) in Russia, and Scandinavian huntergatherers (SHG) in Sweden."[8]

- ^ "[T]he three main groups of Holocene hunter-gatherers (WHG, EHG, SHG)."[8]

- ^ Eastern Hunter Gatherers (EHG) derive 3/4 of their ancestry from the ANE […] Scandinavian hunter-gatherers (SHG) are a mix of EHG and WHG; and WHG are a mix of EHG and the Upper Paleolithic Bichon from Switzerland.[11]

References

- ^ Posth, Cosimo; Yu, He; Ghalichi, Ayshin (March 2023). "Palaeogenomics of Upper Palaeolithic to Neolithic European hunter-gatherers". Nature. 615 (7950): 117–126. Bibcode:2023Natur.615..117P. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-05726-0. hdl:10256/23099. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 9977688. PMID 36859578.

- ^ Kashuba 2019.

- ^ Eisenmann 2018.

- ^ Manninen, Mikael A.; Damlien, Hege; Kleppe, Jan Ingolf; Knutsson, Kjel; Murashkin, Anton; Niemi, Anja R.; Rosenvinge, Carine S.; Persson, Per (April 2021). "First encounters in the north: cultural diversity and gene flow in Early Mesolithic Scandinavia". Antiquity. 95 (380): 310–328. doi:10.15184/aqy.2020.252. hdl:10037/21829. ISSN 0003-598X.

- ^ a b c d Günther et al. 2018.

- ^ Malmström 2009.

- ^ Lazaridis 2014.

- ^ a b c Haak 2015.

- ^ Haak 2015, p. 107, Supplementary Information.

- ^ Mathieson 2015.

- ^ Lazaridis 2016.

- ^ Mittnik 2018.

- ^ Mathieson 2018.

- ^ "This 7,000-year-old woman was among Sweden's last hunter-gatherers". National Geographic Magazine. 11 November 2019. Archived from the original on 3 September 2022.

- ^ "Trelleborgs Museum exhibit". www.trelleborg.se (in Swedish). 1 April 2022.

- ^ Kataoka, Keiichi; Fujita, Hironori; Isa, Mutsumi; Gotoh, Shimpei; Arasaki, Akira; Ishida, Hajime; Kimura, Ryosuke (4 March 2021). "The human EDAR 370V/A polymorphism affects tooth root morphology potentially through the modification of a reaction–diffusion system". Scientific Reports. 11 (1): 5143. Bibcode:2021NatSR..11.5143K. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-84653-4. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 7933414. PMID 33664401.

- ^ Adhikari, Kaustubh; Fuentes-Guajardo, Macarena; Quinto-Sánchez; Mendoza-Revilla; Camilo Chacón-Duque (2016). "A genome-wide association scan implicates DCHS2, RUNX2, GLI3, PAX1 and EDAR in human facial variation". Nature Communications. 7 (1): 11616. Bibcode:2016NatCo...711616A. doi:10.1038/ncomms11616. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 4874031. PMID 27193062.

- ^ Wang, Chuan-Chao; Yeh, Hui-Yuan; Popov, Alexander N.; Zhang, Hu-Qin; Matsumura, Hirofumi; Sirak, Kendra; Cheronet, Olivia; Kovalev, Alexey; Rohland, Nadin; Kim, Alexander M.; Mallick, Swapan; Bernardos, Rebecca; Tumen, Dashtseveg; Zhao, Jing; Liu, Yi-Chang; Liu, Jiun-Yu; Mah, Matthew; Wang, Ke; Zhang, Zhao; Adamski, Nicole; Broomandkhoshbacht, Nasreen; Callan, Kimberly; Candilio, Francesca; Carlson, Kellie Sara Duffett; Culleton, Brendan J.; Eccles, Laurie; Freilich, Suzanne; Keating, Denise; Lawson, Ann Marie; Mandl, Kirsten; Michel, Megan; Oppenheimer, Jonas; Özdoğan, Kadir Toykan; Stewardson, Kristin; Wen, Shaoqing; Yan, Shi; Zalzala, Fatma; Chuang, Richard; Huang, Ching-Jung; Looh, Hana; Shiung, Chung-Ching; Nikitin, Yuri G.; Tabarev, Andrei V.; Tishkin, Alexey A.; Lin, Song; Sun, Zhou-Yong; Wu, Xiao-Ming; Yang, Tie-Lin; Hu, Xi; Chen, Liang; Du, Hua; Bayarsaikhan, Jamsranjav; Mijiddorj, Enkhbayar; Erdenebaatar, Diimaajav; Iderkhangai, Tumur-Ochir; Myagmar, Erdene; Kanzawa-Kiriyama, Hideaki; Nishino, Masato; Shinoda, Ken-ichi; Shubina, Olga A.; Guo, Jianxin; Cai, Wangwei; Deng, Qiongying; Kang, Longli; Li, Dawei; Li, Dongna; Lin, Rong; Shrestha, Rukesh; Wang, Ling-Xiang; Wei, Lanhai; Xie, Guangmao; Yao, Hongbing; Zhang, Manfei; He, Guanglin; Yang, Xiaomin; Hu, Rong; Robbeets, Martine; Schiffels, Stephan; Kennett, Douglas J.; Jin, Li; Li, Hui; Krause, Johannes; Pinhasi, Ron; Reich, David (March 2021). "Genomic insights into the formation of human populations in East Asia". Nature. 591 (7850): 413–419. Bibcode:2021Natur.591..413W. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03336-2. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 7993749. PMID 33618348.

- ^ a b Mathieson 2015: "In three out of six samples, we observe the haplotype carrying the derived allele of rs3827760 in the EDAR gene (Extended Data Fig. 5), which affects tooth morphology and hair thickness33,34, has been the subject of a selective sweep in East Asia35, and today is at high frequency in East Asians and Native Americans. The EDAR derived allele is largely absent in present-day Europe except in Scandinavia, plausibly due to Siberian movements into the region millennia after the date of the Motala samples. The SHG have no evidence of East Asian ancestry4,7, suggesting that the EDAR derived allele may not have originated not in East Asians as previously suggested"

- ^ Zhang, Xiaoming; Ji, Xueping; Li, Chunmei; Yang, Tingyu; Huang, Jiahui; Zhao, Yinhui; Wu, Yun; Ma, Shiwu; Pang, Yuhong; Huang, Yanyi; He, Yaoxi; Su, Bing (25 July 2022). "A Late Pleistocene human genome from Southwest China". Current Biology. 32 (14): 3095–3109.e5. Bibcode:2022CBio...32E3095Z. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2022.06.016. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 35839766. S2CID 250502011. See Figure 5, page 8. "EDAR-V370A emerged the earliest in Amur-19K, Amur-14.5K, and UKY (13.9 kya) in northern East Asia and in the LosRieles (12.0 kya) samples from coastal Chile of South America (E). It was quickly elevated to extremely high frequency in broad East Asia (89.41%) and America (93.33%) during the Early Holocene (F). EDAR-V370A slightly expanded to West Eurasia, and it also appeared at a relatively low frequency in some Central American populations, likely due to the known admixture with Africans and Europeans 500 years ago during the Late Holocene (G). Likewise, the appearance of EDAR-V370A in Oceanians reflects the historic Austronesian dispersal from East Asia to the Pacific Islands about 2,000 years ago (G)."

- ^ Günther et al. (2018): "Interestingly, all individuals exhibited high probabilities of being blue-eyed (0.71-0.92). The Motala2, Motala3, Motala4 and Motala12 individuals most likely had a dark hair color (0.70-0.99), while Motala1 and Motala6 had a light shaded hair (~0.91); they may have been blond (~0.60). Similar to SF9, SF11, SF12, SBj, Hum1, Hum2 and Steigen, the Motala hunter-gatherers presented a combination of light and dark skin pigmentation alleles. Only Motala2 presented exclusively light-skin variants at both rs16891982 and rs1426654." & "Interestingly, the eye and light skin pigmentation phenotypes observed in all SHGs could potentially be explained by admixture between WHG and EHG groups. The high relative-frequency of the blue-eye color allele in SHGs, resembles WHG, while the intermediate frequencies of the skin color determining SNPs in SHGs seem more likely to have come from EHG, since both light-pigmented alleles are virtually absent from WHG. However, for all three well-characterized skin and eye-color associated SNPs, the SHGs display a frequency that is greater for the light-skin variants and the blue-eye variant than can be expected from a mixture of WHGs and EHGs. This observation indicates that the frequencies may have increased due to continued adaptation to a low light conditions."

- ^ Romey 2019.

- ^ Romey 2020.

- ^ Nilsson 2020, The Tybrind girl.

Bibliography

- Eisenmann, Stefanie (29 August 2018). "Reconciling material cultures in archaeology with genetic data: The nomenclature of clusters emerging from archaeogenomic analysis". Scientific Reports. 8 (13003). Nature Research: 13003. Bibcode:2018NatSR...813003E. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-31123-z. PMC 6115390. PMID 30158639.

- Günther, Torsten; Malmström, Helena; Svensson, Emma M.; Omrak, Ayça; Sánchez-Quinto, Federico; Kılınç, Gülşah M.; Krzewińska, Maja; Eriksson, Gunilla; Fraser, Magdalena; Edlund, Hanna; Munters, Arielle R. (9 January 2018). "Population genomics of Mesolithic Scandinavia: Investigating early postglacial migration routes and high-latitude adaptation". PLOS Biology. 16 (1): e2003703. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.2003703. ISSN 1545-7885. PMC 5760011. PMID 29315301.

- Haak, Wolfgang (11 June 2015). "Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe". Nature. 522 (7555). Nature Research: 207–211. arXiv:1502.02783. Bibcode:2015Natur.522..207H. doi:10.1038/nature14317. PMC 5048219. PMID 25731166.

- Kashuba, Natalija (15 May 2019). "Ancient DNA from mastics solidifies connection between material culture and genetics of mesolithic hunter–gatherers in Scandinavia". Communications Biology. 2 (105). Nature Research: 185. doi:10.1038/s42003-019-0399-1. PMC 6520363. PMID 31123709.

- Lazaridis, Iosif (17 September 2014). "Ancient human genomes suggest three ancestral populations for present-day Europeans". Nature. 513 (7518). Nature Research: 409–413. arXiv:1312.6639. Bibcode:2014Natur.513..409L. doi:10.1038/nature13673. hdl:11336/30563. PMC 4170574. PMID 25230663.

- Lazaridis, Iosif (25 July 2016). "Genomic insights into the origin of farming in the ancient Near East". Nature. 536 (7617). Nature Research: 419–424. Bibcode:2016Natur.536..419L. doi:10.1038/nature19310. PMC 5003663. PMID 27459054.

- Malmström, Helena (24 September 2009). "Ancient DNA Reveals Lack of Continuity between Neolithic Hunter-Gatherers and Contemporary Scandinavians". Current Biology. 19 (20). Cell Press: 1758–1762. Bibcode:2009CBio...19.1758M. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2009.09.017. PMC 4275881. PMID 19781941.

- Mathieson, Iain (23 November 2015). "Genome-wide patterns of selection in 230 ancient Eurasians". Nature. 528 (7583). Nature Research: 499–503. Bibcode:2015Natur.528..499M. doi:10.1038/nature16152. PMC 4918750. PMID 26595274.

- Mathieson, Iain (21 February 2018). "The Genomic History of Southeastern Europe". Nature. 555 (7695). Nature Research: 197–203. Bibcode:2018Natur.555..197M. doi:10.1038/nature25778. PMC 6091220. PMID 29466330.

- Mittnik, Alisa (30 January 2018). "The genetic prehistory of the Baltic Sea region". Nature Communications. 16 (1). Nature Research: 442. Bibcode:2018NatCo...9..442M. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-02825-9. PMC 5789860. PMID 29382937.

- Nilsson, Oscar (2020). "Reconstructions". Art & Science by O.D.Nilsson. Archived from the original on 21 October 2020. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- Romey, Kristin (11 November 2019). "Exclusive: This 7,000-Year-Old Woman Was Among Sweden's Last Hunter-Gatherers". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 12 November 2019. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- Romey, Kristin (22 June 2020). "Exclusive: Skull from perplexing ritual site reconstructed". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 22 June 2020. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

Further reading

- Malmström, Helena (30 March 2010). "High frequency of lactose intolerance in a prehistoric hunter-gatherer population in northern Europe". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 10 (1). BioMed Central: 89. Bibcode:2010BMCEE..10...89M. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-10-89. PMC 2862036. PMID 20353605.

- Malmström, Helena (19 January 2015). "Ancient mitochondrial DNA from the northern fringe of the Neolithic farming expansion in Europe sheds light on the dispersion process". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 370 (1660). Royal Society: 20130373. doi:10.1098/rstb.2013.0373. PMC 4275881. PMID 25487325.

- Mittnik, Alisa (7 March 2017). "The Genetic History of Northern Europe". bioRxiv 10.1101/113241.

- Skoglund, Pontus (16 May 2014). "Genomic Diversity and Admixture Differs for Stone-Age Scandinavian Foragers and Farmers". Science. 344 (6185). American Association for the Advancement of Science: 747–750. Bibcode:2014Sci...344..747S. doi:10.1126/science.1253448. PMID 24762536. S2CID 206556994.