Saturn IB

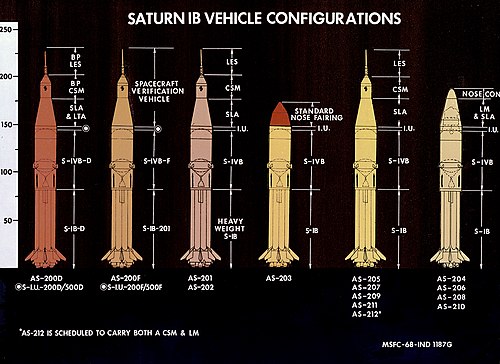

Three launch configurations of the Apollo Saturn IB rocket: no spacecraft (AS-203), command and service module (AS-202), and Lunar Module (Apollo 5) | |

| Function | Apollo spacecraft development; S-IVB stage development in support of Saturn V; Skylab crew launcher |

|---|---|

| Manufacturer | Chrysler (S-IB) Douglas (S-IVB) |

| Country of origin | United States |

| Size | |

| Height | 141.6 ft (43.2 m) without payload[1] |

| Diameter | 21.67 ft (6.61 m)[1] |

| Mass | 1,300,220 lb (589,770 kg) without payload[2] |

| Stages | 2 |

| Capacity | |

| Payload to LEO | |

| Altitude | 87.5 nmi (162.1 km; 100.7 mi) |

| Mass | 21,000 kg (46,000 lb)[3] |

| Launch history | |

| Status | Retired |

| Launch sites | Cape Canaveral, LC-34 and LC-37 Kennedy, LC-39B |

| Total launches | 9 |

| Success(es) | 9 |

| First flight | February 26, 1966 |

| Last flight | July 15, 1975 |

| Type of passengers/cargo | Apollo CSM, Uncrewed Apollo LM |

| First stage – S-IB | |

| Height | 24.44 m (80.17 ft) |

| Diameter | 6.53 m (21.42 ft) |

| Empty mass | 42,000 kg (92,500 lb) |

| Gross mass | 441,000 kg (973,000 lb) |

| Propellant mass | 399,400 kg (880,500 lb) |

| Powered by | 8 × H-1 |

| Maximum thrust | 7,100 kN (1,600,000 lbf) |

| Specific impulse | 272 s (2.67 km/s) |

| Burn time | 150 seconds |

| Propellant | LOX / RP-1 |

| Second stage – S-IVB | |

| Height | 17.81 m (58.42 ft) |

| Diameter | 6.53 m (21.42 ft) |

| Empty mass | 10,600 kg (23,400 lb) |

| Gross mass | 114,300 kg (251,900 lb) |

| Propellant mass | 103,600 kg (228,500 lb) |

| Powered by | 1 × J-2 |

| Maximum thrust | 890 kN (200,000 lbf) |

| Specific impulse | 420 s (4.1 km/s) |

| Burn time | 480 seconds |

| Propellant | LOX / LH2 |

The Saturn IB[a] (also known as the uprated Saturn I) was an American launch vehicle commissioned by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) for the Apollo program. It uprated the Saturn I by replacing the S-IV second stage (90,000-pound-force (400,000 N), 43,380,000 lb-sec total impulse), with the S-IVB (200,000-pound-force (890,000 N), 96,000,000 lb-sec total impulse). The S-IB first stage also increased the S-I baseline's thrust from 1,500,000 pounds-force (6,700,000 N) to 1,600,000 pounds-force (7,100,000 N) and propellant load by 3.1%. This increased the Saturn I's low Earth orbit payload capability from 20,000 pounds (9,100 kg) to 46,000 pounds (21,000 kg), enough for early flight tests of a half-fueled Apollo command and service module (CSM) or a fully fueled Apollo Lunar Module (LM), before the larger Saturn V needed for lunar flight was ready.

By sharing the S-IVB upper stage, the Saturn IB and Saturn V provided a common interface to the Apollo spacecraft. The only major difference was that the S-IVB on the Saturn V burned only part of its propellant to achieve Earth orbit, so it could be restarted for trans-lunar injection. The S-IVB on the Saturn IB needed all of its propellant to achieve Earth orbit.

The Saturn IB launched two uncrewed CSM suborbital flights to a height of 162 km, one uncrewed LM orbital flight, and the first crewed CSM orbital mission (first planned as Apollo 1, later flown as Apollo 7). It also launched one orbital mission, AS-203, without a payload so the S-IVB would have residual liquid hydrogen fuel. This mission supported the design of the restartable version of the S-IVB used in the Saturn V, by observing the behavior of the liquid hydrogen in weightlessness.

In 1973, the year after the Apollo lunar program ended, three Apollo CSM/Saturn IBs ferried crews to the Skylab space station. In 1975, one last Apollo/Saturn IB launched the Apollo portion of the joint US-USSR Apollo–Soyuz Test Project (ASTP). A backup Apollo CSM/Saturn IB was assembled and made ready for a Skylab rescue mission, but never flown.

The remaining Saturn IBs in NASA's inventory were scrapped after the ASTP mission, as no use could be found for them and all heavy lift needs of the US space program could be serviced by the cheaper and more versatile Titan III family and also the Space Shuttle.

History

In 1959, NASA's Silverstein Committee issued recommendations to develop the Saturn class launch vehicles, growing from the C-1. When the Apollo program was started in 1961 with the goal of landing men on the Moon, NASA chose the Saturn I for Earth orbital test missions. However, the Saturn I's payload limit of 20,000 pounds (9,100 kg) to 162 km would allow testing of only the command module with a smaller propulsion module attached, as the command and service module would have a dry weight of at least 26,300 pounds (11,900 kg), in addition to service propulsion and reaction control fuel. In July 1962, NASA announced selection of the C-5 for the lunar landing mission, and decided to develop another launch vehicle by upgrading the Saturn I, replacing its S-IV second stage with the S-IVB, which would also be modified for use as the Saturn V third stage. The S-I first stage would also be upgraded to the S-IB by improving the thrust of its engines and removing some weight. The new Saturn IB, with a payload capability of at least 35,000 pounds (16,000 kg),[4] would replace the Saturn I for Earth orbit testing, allowing the command and service module to be flown with a partial fuel load. It would also allow launching the 32,000-pound (15,000 kg) lunar excursion module separately for uncrewed and crewed Earth orbital testing, before the Saturn V was ready to be flown. It would also give early development to the third stage.[2]

On May 12, 1966, NASA announced the vehicle would be called the "uprated Saturn I", at the same time the "lunar excursion module" was renamed the lunar module. However, the "uprated Saturn I" terminology was reverted to Saturn IB on December 2, 1967.[2]

By the time it was developed, the Saturn IB payload capability had increased to 41,000 pounds (19,000 kg).[2] By 1973, when it was used to launch three Skylab missions, the first-stage engine had been upgraded further, raising the payload capability to 46,000 pounds (21,000 kg).

Specifications

Launch vehicle

| Parameter[1] | S-IB (1st stage) | S-IVB (2nd stage) | Instrument unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Height | 24.44 m (80.17 ft) | 17.81 m (58.42 ft) | 0.91 m (3 ft) |

| Diameter | 6.53 m (21.42 ft) | 6.61 m (21.67 ft) | 6.61 m (21.67 ft) |

| Structural mass | 42,000 kg (92,500 lb) | 10,600 kg (23,400 lb) | 2,000 kg (4,400 lb) |

| Propellant | LOX / RP-1 | LOX / LH2 | — |

| Propellant mass | 399,400 kg (880,500 lb) | 103,600 kg (228,500 lb) | — |

| Engines | 8 × H-1 | 1 × J-2 | — |

| Thrust | 7,100 kN (1,600,000 lbf) sea level | 890 kN (200,000 lbf) vacuum | — |

| Burn duration | 150 seconds | 480 seconds | — |

| Specific impulse | 272 s (2.67 km/s) sea level | 420 s (4.1 km/s) vacuum | — |

| Contractor | Chrysler | Douglas | IBM |

Payload configurations

| Parameter | Command and service module | Apollo 5 | AS-203 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Launch Escape System mass | 4,200 kg (9,200 lb) | — | — |

| Apollo command and service module mass | 16,500 to 20,900 kg (36,400 to 46,000 lb) | — | — |

| Apollo Lunar Module mass | — | 14,360 kg (31,650 lb) | — |

| Spacecraft–LM adapter mass | 1,840 kg (4,050 lb) | 1,840 kg (4,050 lb) | — |

| Nose cone height | — | 2.5 m (8.3 ft) | 8.4 m (27.7 ft) |

| Payload height | 24.9 m (81.8 ft) | 11.1 m (36.3 ft) | — |

| Total space vehicle height | 68.1 m (223.4 ft) | 54.2 m (177.9 ft) | 51.6 m (169.4 ft) |

S-IB first stage

The S-IB stage was built by the Chrysler corporation at the Michoud Assembly Facility, New Orleans.[5] It was powered by eight Rocketdyne H-1 rocket engines burning RP-1 fuel with liquid oxygen (LOX). Eight Redstone tanks (four holding fuel and four holding LOX) were clustered around a Jupiter rocket LOX tank, which earned the rocket the nickname "Cluster's Last Stand".[6] The four outboard engines were mounted on gimbals, allowing them to be steered to control the rocket. Eight fins surrounding the base thrust structure provided aerodynamic stability and control.

Data from:[7]

General characteristics

- Length: 24.44 metres (80.17 ft)

- Diameter: 6.53 metres (21.42 ft)

- Wingspan: 12.02 metres (39.42 ft)

Engine

- 8 × Rocketdyne H-1

S-IVB second stage

The S-IVB was built by the Douglas Aircraft Company at Huntington Beach, California. The S-IVB-200 model was similar to the S-IVB-500 third stage used on the Saturn V, with the exception of the interstage adapter, smaller auxiliary propulsion control modules, and lack of on-orbit engine restart capability. It was powered by a single Rocketdyne J-2 engine. The fuel and oxidizer tanks shared a common bulkhead, which saved about ten tons of weight and reduced vehicle length over ten feet.

General characteristics

- Length: 17.81 metres (58.42 ft)

- Diameter: 6.61 metres (21.67 ft)

Engine

- 1 × Rocketdyne J-2

Instrument unit

IBM built the instrument unit at the Space Systems Center in Huntsville, Alabama. Located at the top of the S-IVB stage, it consisted of a Launch Vehicle Digital Computer (LVDC), an inertial platform, accelerometers, a tracking, telemetry and command system and associated environmental controls. It controlled the entire rocket from just before liftoff until battery depletion. Like other rocket guidance systems, it maintained its state vector (position and velocity estimates) by integrating accelerometer measurements, sent firing and steering commands to the main engines and auxiliary thrusters, and fired the appropriate ordnance and solid rocket motors during staging and payload separation events.

As with other rockets, a completely independent and redundant range safety system could be invoked by ground radio command to terminate thrust and to destroy the vehicle should it malfunction and threaten people or property on the ground. In the Saturn IB and V, the range safety system was permanently disabled by ground command after safely reaching orbit. This was done to ensure that the S-IVB stage would not inadvertently rupture and create a cloud of debris in orbit that could endanger the crew of the Apollo CSM.

Launch sequence events

| Launch event[8] | Time (s) | Altitude (km) | Speed (m/s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Guidance ref release | -5.0 | 0.09 | 0 |

| First motion | 0.0 | 0.09 | 0 |

| Mach 1 | 58.9 | 7.4 | 183 |

| Max dynamic pressure | 73.6 | 12.4 | 328 |

| Freeze tilt | 130.5 | 48.2 | 1587 |

| Inboard engine cutoff | 137.6 | 54.8 | 1845 |

| Outboard engine cutoff | 140.6 | 57.6 | 1903 |

| S-IB / S-IVB separation | 142.0 | 59.0 | 1905 |

| S-IVB ignition | 143.4 | 59.9 | 1900 |

| Ullage case jettison | 154.0 | 69.7 | 1914 |

| Launch escape tower jettison | 165.6 | 79.5 | 1960 |

| Iterative guidance mode initiation | 171.0 | 83.7 | 1984 |

| Engine mixture ratio shift | 469.5 | 164.8 | 5064 |

| Guidance C/O signal | 581.9 | 158.4 | 7419 |

| Orbit insertion | 591.9 | 158.5 | 7426 |

Acceleration of the Saturn IB increased from 1.24 G at liftoff to a maximum of 4.35 G at the end of the S-IB stage burn, and increased again from 0 G to 2.85 G from stage separation to the end of the S-IVB burn.[8]

AS-206, 207, and 208 inserted the Command and Service Module in a 150-by-222-kilometer (81-by-120-nautical-mile) elliptical orbit which was co-planar with the Skylab one. The SPS engine of the Command and Service Module was used at orbit apogee to achieve a Hohmann transfer to the Skylab orbit at 431 kilometers (233 nautical miles).[8]

Saturn IB vehicles and launches

The first five Saturn IB launches for the Apollo program were made from LC-34 and LC-37, Cape Kennedy Air Force Station.

The Saturn IB was used between 1973 and 1975 for three crewed Skylab flights, and one Apollo-Soyuz Test Project flight. This final production run did not have alternating black and white S-IB stage tanks, or vertical stripes on the S-IVB aft tank skirt, which were present on the earlier vehicles. Since LC-34 and 37 were inactive by then, these launches utilized Kennedy Space Center's LC-39B.[9] Mobile Launcher Platform No. 1 was modified, adding an elevated platform known as the "milkstool" to accommodate the height differential between the Saturn IB and the much larger Saturn V.[9] This enabled alignment of the Launch Umbilical Tower's access arms to accommodate crew access, fueling, and ground electrical connections for the Apollo spacecraft and S-IVB upper stage. The tower's second stage access arms were modified to service the S-IB first stage.[9]

| Serial number |

Launch date (UTC) |

Launch site | Mission | Spacecraft mass (kg) |

Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SA-201 | February 26, 1966 16:12:01 |

Cape Kennedy, LC-34 | AS-201 | 20,820 | Uncrewed suborbital test of Block I CSM (command and service module) |

| SA-203 | July 5, 1966 14:53:17 |

Cape Kennedy, LC-37B | AS-203 | None | Uncrewed test of unburned LH2 behavior in orbit to support S-IVB-500 restart design |

| SA-202 | August 25, 1966 17:15:32 |

Cape Kennedy, LC-34 | AS-202 | 25,810 | Uncrewed suborbital test of Block I CSM |

| SA-204 | Cape Kennedy, LC-34 | Apollo 1 | 20,412 | Was to be first crewed orbital test of Block I CSM. Cabin fire on January 27, 1967, killed astronauts and damaged CM during dress rehearsal for planned February 21, 1967 launch | |

| January 22, 1968 22:48:08 |

Cape Kennedy, LC-37B | Apollo 5 | 14,360 | Uncrewed orbital test of lunar module, used Apollo 1 launch vehicle | |

| SA-205 | October 11, 1968 15:02:45 |

Cape Kennedy, LC-34 | Apollo 7 | 16,520 | Crewed orbital test of Block II CSM |

| SA-206 | May 25, 1973 13:00:00 |

Kennedy, LC-39B | Skylab 2 | 19,979 | Block II CSM ferried first crew to Skylab orbital workshop |

| SA-207 | July 28, 1973 11:10:50 |

Kennedy, LC-39B | Skylab 3 | 20,121 | Block II CSM ferried second crew to Skylab orbital workshop |

| SA-208 | Kennedy, LC-39B | AS-208 | Standby Skylab 3 rescue CSM-119; not needed | ||

| November 16, 1973 14:01:23 |

Kennedy, LC-39B | Skylab 4 | 20,847 | Block II CSM ferried third crew to Skylab orbital workshop | |

| SA-209 | Kennedy, LC-39B | AS-209 | Standby Skylab 4 and later Apollo-Soyuz rescue CSM-119. Not needed, currently on display in the KSC rocket garden | ||

| Skylab 5 | Planned CSM mission to lift Skylab workshop's orbit to endure until Space Shuttle ready to fly; cancelled. | ||||

| SA-210 | July 15, 1975 19:50:01 |

Kennedy, LC-39B | ASTP | 16,780 | Apollo CSM with special docking adapter module, rendezvoused with Soyuz 19. Last Saturn IB flight. |

| SA-211 | Unused. First stage was on display at the Alabama Welcome Center on I-65 in Ardmore, Alabama from 1979 to 2023: Now dismantled for disposal.[10] S-IVB stage rests with Skylab underwater training simulator hardware and is on display outdoors at the U.S. Space and Rocket Center in Huntsville, Alabama. | ||||

| SA-212 | Unused. First stage scrapped.[5] S-IVB stage converted to Skylab space station. | ||||

| SA-213 | Only first stage built. Unused and scrapped.[5] | ||||

| SA-214 | Only first stage built. Unused and scrapped.[5] | ||||

For earlier launches of vehicles in the Saturn I series, see the list in the Saturn I article.

Saturn IB rockets on display

As of 2023 there are two locations where Saturn IB vehicles (or parts thereof) are on display:

- SA-209 is on display at the Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex, with the Apollo Facilities Verification Vehicle. Due to severe corrosion, the first stage engines and service module were replaced with fabricated duplicates in 1993–1994.

- The SA-211 S-IVB stage was mated with the Skylab underwater training docking adapter and Apollo Telescope Mount and is on display in the Rocket Garden of the U.S. Space & Rocket Center in Huntsville, Alabama. The SA-211 first stage was on display with a mockup S-IVB stage stacked in a launch-ready condition at the Alabama Welcome Center on Interstate 65 in Ardmore, Alabama, since July 1979.34°57′16″N 86°53′31″W / 34.954548°N 86.89193°W[11][12] The structural integrity of the display, after four decades of weathering, could not be repaired. Dismantling of the vehicle for disposal began by September 14, 2023.[10]

Cost

In 1972, the cost of a Saturn IB including launch was US$55,000,000 (equivalent to $401,000,000 in 2023).[13]

See also

Notes

- ^ Pronounced "saturn one bee"

References

- ^ a b c Postlaunch report for mission AS-201 (Apollo spacecraft 009) - (PDF), NASA, May 1966, retrieved March 18, 2011

- ^ a b c d Wade, Mark. "Saturn IB". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Archived from the original on May 14, 2011. Retrieved March 17, 2011.

- ^ Hornung, John (2013). Entering the Race to the Moon: Autobiography of an Apollo Rocket Scientist. Williamsburg, Virginia: Jack Be Nimble Publishing. ISBN 9780983044178.

- ^ Benson, Charles D.; Faherty, William Barnaby (1978). "The Apollo-Saturn IB Space Vehicle". Moonport: A History of Apollo Launch Facilities and Operations. NASA. Archived from the original on 24 March 2016. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ^ a b c d "Saturn IB History". Archived from the original on January 4, 2013. Retrieved 2009-11-01.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Saturn I".

- ^ NASA Marshall Spaceflight Center, Skylab Saturn IB Flight Manual (MSFC-MAN-206), 30 September 1972

- ^ a b c Skylab Saturn 1B Flight Manual - (PDF), NASA, September 30, 1972, retrieved July 8, 2020

- ^ a b c Reynolds, David West (2006). Kennedy Space Center: Gateway to Space. Richmond Hill, Ontario: Firefly Books Ltd. pp. 154–157. ISBN 978-1-55407-039-8.

- ^ a b "Historic Alabama welcome center rocket dismantling begins". 14 September 2023. Retrieved 2023-09-20.

- ^ Dooling, Dave (May 6, 1979). "Space and Rocket Plans Summer Celebration". The Huntsville Times.

- ^ Hughes, Bayne (April 6, 2014). "Iconic rocket due for repair". The Decatur Daily. Retrieved April 8, 2014.

- ^ "SP-4221 The Space Shuttle Decision- Chapter 6: Economics and the Shuttle". NASA. Retrieved 2011-01-15.

External links

- http://www.apollosaturn.com/

- http://www.spaceline.org/rocketsum/saturn-Ib.html

- NASA Marshall Spaceflight Center, "Skylab Saturn IB Flight Manual" (PDF). (19.8 MB), 30 September 1972

- "Saturn launch vehicles" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2005-04-16. (61.2 MB)