San people

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| ca. 160,000 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 71,201 (2023 census)[1] | |

| 63,500 | |

| ca. 7,000 | |

| ca. 16,000 | |

| 1,200 | |

| Languages | |

| Languages of the Khoe, Kxʼa, and Tuu families, English, Portuguese, Afrikaans | |

| Religion | |

| San religion, Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Khoekhoe, Coloureds, Basters, Griqua, Sotho, Xhosa, Zulu, Swazi, Ndebele, Pedi, Tswana, Lozi | |

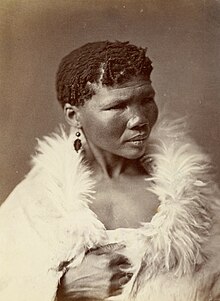

The San peoples (also Saan), or Bushmen, are the members of any of the indigenous hunter-gatherer cultures of southern Africa, and the oldest surviving cultures of the region.[2] They are thought to have diverged from other humans 100,000 to 200,000 years ago.[a][4] Their recent ancestral territories span Botswana, Namibia, Angola, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Lesotho,[5] and South Africa.

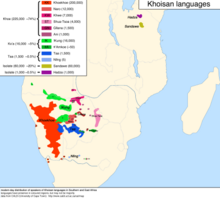

The San speak, or their ancestors spoke, languages of the Khoe, Tuu, and Kxʼa language families, and can be defined as a people only in contrast to neighboring pastoralists such as the Khoekhoe and descendants of more recent waves of immigration such as the Bantu, Europeans, and Asians.

In 2017, Botswana was home to approximately 63,500 San, making it the country with the highest proportion of San people at 2.8%.[6] 71,201 San people were enumerated in Namibia in 2023, making it the country with the second highest proportion of San people at 2.4%.[1]

Definition

In Khoekhoegowab, the term "San" has a long vowel and is spelled Sān. It is an exonym meaning "foragers" and is used in a derogatory manner to describe people too poor to have cattle. Based on observation of lifestyle, this term has been applied to speakers of three distinct language families living between the Okavango River in Botswana and Etosha National Park in northwestern Namibia, extending up into southern Angola; central peoples of most of Namibia and Botswana, extending into Zambia and Zimbabwe; and the southern people in the central Kalahari towards the Molopo River, who are the last remnant of the previously extensive indigenous peoples of southern Africa.[7]

Names

The designations "Bushmen" and "San" are both exonyms. The San have no collective word for themselves in their own languages. "San" comes from a derogatory Khoekhoe word used to refer to foragers without cattle or other wealth, from a root saa "picking up from the ground" + plural -n in the Haiǁom dialect.[8][9]

"Bushmen" is the older cover term, but "San" was widely adopted in the West by the late 1990s. The term Bushmen, from 17th-century Dutch Bosjesmans, is still used by others and to self-identify, but is now considered pejorative or derogatory by many South Africans.[10][11][12][13][14] In 2008, the use of boesman (the modern Afrikaans equivalent of "Bushman") in the Die Burger newspaper was brought before the Equality Court. The San Council testified that it had no objection to its use in a positive context, and the court ruled that the use of the term was not derogatory.[15]

The San refer to themselves as their individual nations, such as ǃKung (also spelled ǃXuun, including the Juǀʼhoansi), ǀXam, Nǁnǂe (part of the ǂKhomani), Kxoe (Khwe and ǁAni), Haiǁom, Ncoakhoe, Tshuwau, Gǁana and Gǀui (ǀGwi), etc.[16][17][10][18][19] Representatives of San peoples in 2003 stated their preference for the use of such individual group names, where possible, over the use of the collective term San.[20]

Adoption of the Khoekhoe term San in Western anthropology dates to the 1970s, and this remains the standard term in English-language ethnographic literature, although some authors later switched back to using the name Bushmen.[7][21] The compound Khoisan is used to refer to the pastoralist Khoi and the foraging San collectively. It was coined by Leonhard Schulze in the 1920s and popularized by Isaac Schapera in 1930. Anthropological use of San was detached from the compound Khoisan,[22] as it has been reported that the exonym San is perceived as a pejorative in parts of the central Kalahari.[11] By the late 1990s, the term San was used generally by the people themselves.[23] The adoption of the term was preceded by a number of meetings held in the 1990s where delegates debated on the adoption of a collective term.[24] These meetings included the Common Access to Development Conference organized by the Government of Botswana held in Gaborone in 1993,[18] the 1996 inaugural Annual General Meeting of the Working Group of Indigenous Minorities in Southern Africa (WIMSA) held in Namibia,[25] and a 1997 conference in Cape Town on "Khoisan Identities and Cultural Heritage" organized by the University of the Western Cape.[26] The term San is now standard in South African, and used officially in the blazon of the national coat-of-arms. The "South African San Council" representing San communities in South Africa was established as part of WIMSA in 2001.[27][28]

The term Basarwa (singular Mosarwa) is used for the San collectively in Botswana.[29][30][31] The term is a Bantu (Tswana) word meaning "those who do not rear cattle", that is, equivalent to Khoekhoe Saan.[32] The mo-/ba- noun class prefixes are used for people; the older variant Masarwa, with the le-/ma- prefixes used for disreputable people and animals, is offensive and was changed at independence.[26][33]

In Angola, they are sometimes referred to as mucancalas,[34] or bosquímanos (a Portuguese adaptation of the Dutch term for "Bushmen"). The terms Amasili and Batwa are sometimes used for them in Zimbabwe.[26] The San are also referred to as Batwa by Xhosa people and as Baroa by Sotho people.[35] The Bantu term Batwa refers to any foraging tribesmen and as such overlaps with the terminology used for the "Pygmoid" Southern Twa of South-Central Africa.

History

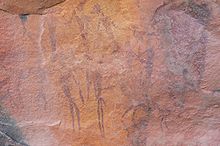

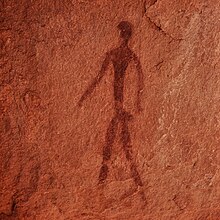

The hunter-gatherer San are among the oldest cultures on Earth,[36] and are thought to be descended from the first inhabitants of what is now Botswana and South Africa. The historical presence of the San in Botswana is particularly evident in northern Botswana's Tsodilo Hills region. San were traditionally semi-nomadic, moving seasonally within certain defined areas based on the availability of resources such as water, game animals, and edible plants.[37] Peoples related to or similar to the San occupied the southern shores throughout the eastern shrubland and may have formed a Sangoan continuum from the Red Sea to the Cape of Good Hope.[38] Early San society left a rich legacy of cave paintings across Southern Africa.[39]: 11–12

In the Bantu expansion (2000 BC - 1000 AD), San were driven off their ancestral lands or incorporated by Bantu speaking groups.[39]: 11–12 The San were believed to have closer connections to the old spirits of the land, and were often turned to by other societies for rainmaking, as was the case at Mapungubwe. San shamans would enter a trance and go into the spirit world themselves to capture the animals associated with rain.[40]

By the end of the 18th century after the arrival of the Dutch, thousands of San had been killed and forced to work for the colonists. The British tried to "civilize" the San and make them adopt a more agricultural lifestyle, but were not successful. By the 1870s, the last San of the Cape were hunted to extinction, while other San were able to survive. The South African government used to issue licenses for people to hunt the San, with the last one being reportedly issued in Namibia in 1936.[41]

From the 1950s through to the 1990s, San communities switched to farming because of government-mandated modernization programs. Despite the lifestyle changes, they have provided a wealth of information in anthropology and genetics. One broad study of African genetic diversity, completed in 2009, found that the genetic diversity of the San was among the top five of all 121 sampled populations.[42][43][44] Certain San groups are one of 14 known extant "ancestral population clusters"; that is, "groups of populations with common genetic ancestry, who share ethnicity and similarities in both their culture and the properties of their languages".[43]

Despite some positive aspects of government development programs reported by members of San and Bakgalagadi communities in Botswana, many have spoken of a consistent sense of exclusion from government decision-making processes, and many San and Bakgalagadi have alleged experiencing ethnic discrimination on the part of the government.[37]: 8–9 The United States Department of State described ongoing discrimination against San, or Basarwa, people in Botswana in 2013 as the "principal human rights concern" of that country.[45]: 1

Society

The San kinship system reflects their history as traditionally small mobile foraging bands. San kinship is similar to Inuit kinship, which uses the same set of terms as in European cultures but adds a name rule and an age rule for determining what terms to use. The age rule resolves any confusion arising from kinship terms, as the older of two people always decides what to call the younger. Relatively few names circulate (approximately 35 names per sex), and each child is named after a grandparent or another relative, but never their parents.

Children have no social duties besides playing, and leisure is very important to San of all ages. Large amounts of time are spent in conversation, joking, music, and sacred dances. Women may be leaders of their own family groups. They may also make important family and group decisions and claim ownership of water holes and foraging areas. Women are mainly involved in the gathering of food, but sometimes also partake in hunting.[46]

Water is important in San life. During long droughts, they make use of sip wells in order to collect water. To make a sip well, a San scrapes a deep hole where the sand is damp, and inserts a long hollow grass stem into the hole. An empty ostrich egg is used to collect the water. Water is sucked into the straw from the sand, into the mouth, and then travels down another straw into the ostrich egg.[46]

Traditionally, the San were an egalitarian society.[47] Although they had hereditary chiefs, their authority was limited. The San made decisions among themselves by consensus, with women treated as relative equals in decision making.[48] San economy was a gift economy, based on giving each other gifts regularly rather than on trading or purchasing goods and services.[49]

Most San are monogamous, but if a hunter is able to obtain enough food, he can afford to have a second wife as well.[50]

Subsistence

Villages range in sturdiness from nightly rain shelters in the warm spring (when people move constantly in search of budding greens), to formalized rings, wherein people congregate in the dry season around permanent waterholes. Early spring is the hardest season: a hot dry period following the cool, dry winter. Most plants still are dead or dormant, and supplies of autumn nuts are exhausted. Meat is particularly important in the dry months when wildlife cannot range far from the receding waters.

Women gather fruit, berries, tubers, bush onions, and other plant materials for the band's consumption. Ostrich eggs are gathered, and the empty shells are used as water containers. Insects provide perhaps 10% of animal proteins consumed, most often during the dry season.[51] Depending on location, the San consume 18 to 104 species, including grasshoppers, beetles, caterpillars, moths, butterflies, and termites.[52]

Women's traditional gathering gear is simple and effective: a hide sling, a blanket, a cloak called a kaross to carry foodstuffs, firewood, smaller bags, a digging stick, and perhaps, a smaller version of the kaross to carry a baby.

Men, and presumably women when they accompany them, hunt in long, laborious tracking excursions. They kill their game using bow and arrows and spears tipped in diamphotoxin, a slow-acting arrow poison produced by beetle larvae of the genus Diamphidia.[53]

Early history

A set of tools almost identical to that used by the modern San and dating to 42,000 BC was discovered at Border Cave in KwaZulu-Natal in 2012.[54]

In 2006, what is thought to be the world's oldest ritual is interpreted as evidence which would make the San culture the oldest still practiced culture today. [55] [56] [57] [58]

Historical evidence shows that certain San communities have always lived in the desert regions of the Kalahari; however, eventually nearly all other San communities in southern Africa were forced into this region. The Kalahari San remained in poverty where their richer neighbours denied them rights to the land. Before long, in both Botswana and Namibia, they found their territory drastically reduced.[59]

Genetics

Various Y chromosome studies show that the San carry some of the most divergent (earliest branching) human Y-chromosome haplogroups. These haplogroups are specific sub-groups of haplogroups A and B, the two earliest branches on the human Y-chromosome tree.[60][61][62]

Mitochondrial DNA studies also provide evidence that the San carry high frequencies of the earliest haplogroup branches in the human mitochondrial DNA tree. This DNA is inherited only from one's mother. The most divergent (earliest branching) mitochondrial haplogroup, L0d, has been identified at its highest frequencies in the southern African San groups.[60][63][64][65]

In a study published in March 2011, Brenna Henn and colleagues found that the ǂKhomani San, as well as the Sandawe and Hadza peoples of Tanzania, were the most genetically diverse of any living humans studied. This high degree of genetic diversity hints at the origin of anatomically modern humans.[66][67]

A 2008 study suggested that the San may have been isolated from other original ancestral groups for as much as 50,000 to 100,000 years and later rejoined, re-integrating into the rest of the human gene pool.[68]

A DNA study of fully sequenced genomes, published in September 2016, showed that the ancestors of today's San hunter-gatherers began to diverge from other human populations in Africa about 200,000 years ago and were fully isolated by 100,000 years ago.[69]

Ancestral land conflict in Botswana

According to professors Robert K. Hitchcock, Wayne A. Babchuk, "In 1652, when Europeans established a full-time presence in Southern Africa, there were some 300,000 San and 600,000 Khoekhoe in Southern Africa. During the early phases of European colonization, tens of thousands of Khoekhoe and San peoples lost their lives as a result of genocide, murder, physical mistreatment, and disease. There were cases of “Bushman hunting” in which commandos (mobile paramilitary units or posses) sought to dispatch San and Khoekhoe in various parts of Southern Africa."[70]

Much aboriginal people's land in Botswana, including land occupied by the San people (or Basarwa), was conquered during colonization. Loss of land and access to natural resources continued after Botswana's independence.[37]: 2 The San have been particularly affected by encroachment by majority peoples and non-indigenous farmers onto their traditional land. Government policies from the 1970s transferred a significant area of traditionally San land to majority agro-pastoralist tribes and white settlers[37]: 15 Much of the government's policy regarding land tended to favor the dominant Tswana peoples over the minority San and Bakgalagadi.[37]: 2 Loss of land is a major contributor to the problems facing Botswana's indigenous people, including especially the San's eviction from the Central Kalahari Game Reserve.[37]: 2 The government of Botswana decided to relocate all of those living within the reserve to settlements outside it. Harassment of residents, dismantling of infrastructure, and bans on hunting appear to have been used to induce residents to leave.[37]: 16 The government has denied that any of the relocation was forced.[71] A legal battle followed.[72] The relocation policy may have been intended to facilitate diamond mining by Gem Diamonds within the reserve.[37]: 18

Hoodia traditional knowledge agreement

Hoodia gordonii, used by the San, was patented by the South African Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) in 1998, for its presumed appetite suppressing quality, although, according to a 2006 review, no published scientific evidence supported hoodia as an appetite suppressant in humans.[73] A licence was granted to Phytopharm, for development of the active ingredient in the Hoodia plant, p57 (glycoside), to be used as a pharmaceutical drug for dieting. Once this patent was brought to the attention of the San, a benefit-sharing agreement was reached between them and the CSIR in 2003. This would award royalties to the San for the benefits of their indigenous knowledge.[74] During the case, the San people were represented and assisted by the Working Group of Indigenous Minorities in Southern Africa (WIMSA), the South African San Council and the South African San Institute.[27][28]

This benefit-sharing agreement is one of the first to give royalties to the holders of traditional knowledge used for drug sales. The terms of the agreement are contentious, because of their apparent lack of adherence to the Bonn Guidelines on Access to Genetic Resources and Benefit Sharing, as outlined in the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD).[75] The San have yet to profit from this agreement, as P57 has still not yet been legally developed and marketed.

Representation in mass media

Early representations

The San of the Kalahari were first brought to the globalized world's attention in the 1950s by South African author Laurens van der Post. Van der Post grew up in South Africa, and had a respectful lifelong fascination with native African cultures. In 1955, he was commissioned by the BBC to go to the Kalahari desert with a film crew in search of the San. The filmed material was turned into a very popular six-part television documentary a year later. Driven by a lifelong fascination with this "vanished tribe," Van der Post published a 1958 book about this expedition, entitled The Lost World of the Kalahari. It was to be his most famous book.

In 1961, he published The Heart of the Hunter, a narrative which he admits in the introduction uses two previous works of stories and mythology as "a sort of Stone Age Bible," namely Specimens of Bushman Folklore' (1911), collected by Wilhelm H. I. Bleek and Lucy C. Lloyd, and Dorothea Bleek's Mantis and His Friend. Van der Post's work brought indigenous African cultures to millions of people around the world for the first time, but some people disparaged it as part of the subjective view of a European in the 1950s and 1960s, stating that he branded the San as simple "children of Nature" or even "mystical ecologists." In 1992 by John Perrot and team published the book "Bush for the Bushman" – a "desperate plea" on behalf of the aboriginal San addressing the international community and calling on the governments throughout Southern Africa to respect and reconstitute the ancestral land-rights of all San.

Documentaries and non-fiction

John Marshall, the son of Harvard anthropologist Lorna Marshall, documented the lives of San in the Nyae Nyae region of Namibia over a period spanning more than 50-years. His early film The Hunters, shows a giraffe hunt. A Kalahari Family (2002) is a series documenting 50 years in the lives of the Juǀʼhoansi of Southern Africa, from 1951 to 2000. Marshall was a vocal proponent of the San cause throughout his life.[76] His sister Elizabeth Marshall Thomas wrote several books and numerous articles about the San, based in part on her experiences living with these people when their culture was still intact. The Harmless People, published in 1959, and The Old Way: A Story of the First People, published in 2006, are two of them. John Marshall and Adrienne Miesmer documented the lives of the ǃKung San people between the 1950s and 1978 in Nǃai, the Story of a ǃKung Woman.[77][78] This film, the account of a woman who grew up while the San lived as autonomous hunter-gatherers, but who later was forced into a dependent life in the government-created community at Tsumkwe, shows how the lives of the ǃKung people, who lived for millennia as hunter gatherers, were forever changed when they were forced onto a reservation too small to support them.[79]

South African film-maker Richard Wicksteed has produced a number of documentaries on San culture, history and present situation; these include In God's Places / Iindawo ZikaThixo (1995) on the San cultural legacy in the southern Drakensberg; Death of a Bushman (2002) on the murder of San tracker Optel Rooi by South African police; The Will To Survive (2009), which covers the history and situation of San communities in southern Africa today; and My Land is My Dignity (2009) on the San's epic land rights struggle in Botswana's Central Kalahari Game Reserve.

A documentary on San hunting entitled, The Great Dance: A Hunter's Story (2000), directed by Damon and Craig Foster. This was reviewed by Lawrence Van Gelder for the New York Times, who said that the film "constitutes an act of preservation and a requiem."[80]

Spencer Wells's 2003 book The Journey of Man—in connection with National Geographic's Genographic Project—discusses a genetic analysis of the San and asserts their genetic markers were the first ones to split from those of the ancestors of the bulk of other Homo sapiens sapiens. The PBS documentary based on the book follows these markers throughout the world, demonstrating that all of humankind can be traced back to the African continent (see Recent African origin of modern humans, the so-called "out of Africa" hypothesis).

The BBC's The Life of Mammals (2003) series includes video footage of an indigenous San of the Kalahari desert undertaking a persistence hunt of a kudu through harsh desert conditions.[81] It provides an illustration of how early man may have pursued and captured prey with minimal weaponry.

The BBC series How Art Made the World (2005) compares San cave paintings from 200 years ago to Paleolithic European paintings that are 14,000 years old.[82] Because of their similarities, the San works may illustrate the reasons for ancient cave paintings. The presenter Nigel Spivey draws largely on the work of Professor David Lewis-Williams,[83] whose PhD was entitled "Believing and Seeing: Symbolic meanings in southern San rock paintings". Lewis-Williams draws parallels with prehistoric art around the world, linking in shamanic ritual and trance states.

Films and music

A 1969 film, Lost in the Desert, features a small boy, stranded in the desert, who encounters a group of wandering San. They help him and then abandon him as a result of a misunderstanding created by the lack of a common language and culture. The film was directed by Jamie Uys, who returned to the San a decade later with The Gods Must Be Crazy, which proved to be an international hit. This comedy portrays a Kalahari San group's first encounter with an artifact from the outside world (a Coca-Cola bottle). By the time this movie was made, the ǃKung had recently been forced into sedentary villages, and the San hired as actors were confused by the instructions to act out inaccurate exaggerations of their almost abandoned hunting and gathering life.[84]

"Eh Hee" by Dave Matthews Band was written as an evocation of the music and culture of the San. In a story told to the Radio City audience (an edited version of which appears on the DVD version of Live at Radio City), Matthews recalls hearing the music of the San and, upon asking his guide what the words to their songs were, being told that "there are no words to these songs, because these songs, we've been singing since before people had words." He goes on to describe the song as his "homage to meeting... the most advanced people on the planet."

Memoirs

In Peter Godwin's biography When A Crocodile Eats the Sun, he mentions his time spent with the San for an assignment. His title comes from the San's belief that a solar eclipse occurs when a crocodile eats the sun.

Novels

Laurens van der Post's two novels, A Story Like The Wind (1972) and its sequel, A Far Off Place (1974), made into a 1993 film, are about a white boy encountering a wandering San and his wife, and how the San's life and survival skills save the white teenagers' lives in a journey across the desert.

James A. Michener's The Covenant (1980), is a work of historical fiction centered on South Africa. The first section of the book concerns a San community's journey set roughly in 13,000 BC.

In Wilbur Smith's novel The Burning Shore (an instalment in the Courtneys of Africa book series), the San people are portrayed through two major characters, O'wa and H'ani; Smith describes the San's struggles, history, and beliefs in great detail.

Norman Rush's 1991 novel Mating features an encampment of Basarwa near the (imaginary) Botswana town where the main action is set.

Tad Williams's epic Otherland series of novels features a South African San named ǃXabbu, whom Williams confesses to be highly fictionalized, and not necessarily an accurate representation. In the novel, Williams invokes aspects of San mythology and culture.

In 2007, David Gilman published The Devil's Breath. One of the main characters, a small San boy named ǃKoga, uses traditional methods to help the character Max Gordon travel across Namibia.

Alexander McCall Smith has written a series of episodic novels set in Gaborone, the capital of Botswana. The fiancé of the protagonist of The No. 1 Ladies' Detective Agency series, Mr. J. L. B. Matekoni, adopts two orphaned San children, sister and brother Motholeli and Puso.

The San feature in several of the novels by Michael Stanley (the nom de plume of Michael Sears and Stanley Trollip), particularly in Death of the Mantis.

In Christopher Hope's book Darkest England, the San hero, David Mungo Booi, is tasked by his fellow tribesmen with asking the Queen for the protection once promised, and to evaluate the possibility of creating a colony on the island. He discovered England in the manner of 19th century Western explorers.

Notable individuals

ǃKung

Gǁana

ǀXam

Nǁnǂe

Naro

ǂKhomani

Notes

See also

- First People of the Kalahari

- Kalahari Debate

- Khoisan

- Negro of Banyoles

- Botswanan art#San art

- Strandloper

- Vaalpens

- Boskop Man

References

- ^ a b "Namibia 2023 Population and Housing Census Main Report" (PDF). Namibia Statistics Agency. Retrieved 30 October 2024.

- ^ "Foragers to First Peoples: The Kalahari San Today | Cultural Survival". www.culturalsurvival.org. 28 April 2010. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ Pargeter, Justin; Mackay, Alex; Mitchell, Peter; Shea, John; Stewart, Brian (2016). "Primordialism and the 'Pleistocene San' of southern Africa". Antiquity. 90 (352).

- ^ Al-Hindi, Dana R.; Reynolds, Austin W.; Henn, Brenna M. (2022), Grine, Frederick E. (ed.), "Genetic Divergence Within Southern Africa During the Later Stone Age", Hofmeyr: A Late Pleistocene Human Skull from South Africa, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 19–28, doi:10.1007/978-3-031-07426-4_3, ISBN 978-3-031-07426-4, retrieved 2 January 2025

- ^ Walsham How, Marion (1962). The Mountain Bushmen of Basutoland. Pretoria: J. L. Van Schaik Ltd.

- ^ Hitchcock, Robert K.; Sapignoli, Maria (8 May 2019). "The economic wellbeing of the San of the western, central and eastern Kalahari regions of Botswana". In Fleming, Christopher; Manning, Matthew (eds.). Routledge Handbook of Indigenous Wellbeing (1st ed.). Routledge. pp. 170–183. ISBN 9781138909175 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ a b Barnard, Alan (2007). Anthropology and the Bushman. Oxford: Berg. pp. 4–7. ISBN 9781847883308.

- ^ "WIMSA Annual Report 2004-05". WIMSA. p. 58. Archived from the original on 18 March 2014. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

the term 'San' comes from the Haiǁom language and has been abbreviated in the following way ... Saa – Picking things up (food) from the ground (i.e. 'gathering'), Saab – A male person gathering, Saas – A female person gathering, Saan – Many people gathering, San – One way to write 'all of the people gathering'

- ^ "The old Dutch also did not know that their so-called Hottentots formed only one branch of a wide-spread race, of which the other branch divided into ever so many tribes, differing from each other totally in language [...] While the so-called Hottentots called themselves Khoikhoi (men of men, i.e. men par excellence), they called those other tribes Sā, the Sonqua of the Cape Records [...] We should apply the term Hottentot to the whole race, and call the two families, each by the native name, that is the one, the Khoikhoi, the so-called Hottentot proper; the other the San (Sā) or Bushmen." – Theophilus Hahn, Tsuni-ǁGoam: The Supreme Being to the Khoi-Khoi (1881), p. 3.

- ^ a b Ouzman, Sven (2004). "Silencing and Sharing Southern Africa Indigenous and Embedded Knowledge". In Smith, Claire; Wobst, H. Martin (eds.). Indigenous Archaeologies: Decolonizing Theory and Practice. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group. p. 209. ISBN 9781134391554.

- ^ a b Mountain, Alan (2003). First People of the Cape. Claremont: New Africa Books. pp. 23–24. ISBN 9780864866233.

- ^ Guenther, Mathias (2006). "Contemporary Bushman Art, Identity Politics, and the Primitivism Discourse". In Solway, Jacqueline (ed.). The Politics of Egalitarianism: Theory and Practice. New York: Berghahn Books. pp. 181–182. ISBN 9781845451158.

- ^ Britten, Sarah (2007). McBride of Frankenmanto: The Return of the South African Insult. Johannesburg: 30° South. pp. 18–19. ISBN 9781920143183.

- ^ Adhikari, Mohamed (2009). Not White Enough, Not Black Enough: Racial Identity in the South African Coloured Community. Ohio University Press. p. 28. ISBN 9780896804425.

- ^ "Use of the word 'boesman' not hate speech, court finds". Mail & Guardian. 11 April 2008. Schroeder, Fatima (14 April 2008). "Court: Use of 'boesman' not hate speech". IOL. "Objectively speaking and taking into account the context in which (Die Burger) published the word 'boesman' and the evidence of the San Council witness, I find that the usage of the word did not cause harm, hostility or hatred. Instead, the San Council's representative was adamant that no hurt or harm was caused to them or the San community with the manner in which (Die Burger) published the word 'boesman'."

- ^ Lee, Richard B. and Daly, Richard Heywood (1999) The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Hunters and Gatherers, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 052157109X

- ^ Smith, Andrew Brown (2000). The Bushmen of Southern Africa: A Foraging Society in Transition. Cape Town: New Africa Books. p. 2. ISBN 9780864864192.

- ^ a b "San, Bushmen or Basarwa: What's in a name?". Mail & Guardian. 5 September 2007. Archived from the original on 17 January 2012.

- ^ Coan, Stephen (28 July 2010). "The first people". The Witness. Archived from the original on 14 October 2013.

- ^ Statement by delegates of the Working Group of Indigenous Minorities in Southern Africa (WIMSA) and the South African San Institute attending the 2003 Africa Human Genome Initiative conference held in Stellenbosch. Schlebusch, Carina (25 March 2010). "Issues raised by use of ethnic-group names in genome study". Nature. 464 (7288): 487. Bibcode:2010Natur.464..487S. doi:10.1038/464487a. PMID 20336115.

- ^ Sailer, Steve (20 June 2002). "Feature: Name game – 'Inuit' or 'Eskimo'?". UPI. "The fashion of renaming the Bushmen of Southwestern Africa as the 'San' exemplifies many of the problems with the name game. University of Utah anthropologist Henry Harpending, who has lived with the famous tongue-clicking hunter-gatherers said, 'In the 1970s the name "San" spread in Europe and America because it seemed to be politically correct, while 'Bushmen' sounded derogatory and sexist.' Unfortunately, the hunter-gatherers never actually had a collective name for themselves in any of their own languages. 'San' was actually the insulting word that the herding Khoi people called the Bushmen. [...] Harpending noted, 'The problem was that in the Kalahari, "San" has all the baggage that the "N-word" has in America. Bushmen kids are graduating from school, reading the academic literature, and are outraged that we call them "San." [...] one did not call someone a San to his face. I continued to use Bushman, and I was publicly corrected several times by the righteous. It quickly became a badge among Western academics: If you say "San" and I say "San," then we signal each other that we are on the fashionable side, politically. It had nothing to do with respect. I think most politically correct talk follows these dynamics.'"

- ^ "Schapera is the author of the convenient term Khoisan, compounded of the Hottentot's name for themselves (Khoi) and their name for the Bushmen (San)." Joseph Greenberg, The Languages of Africa (1963), p. 66.

- ^ Lee, Richard B. (2012). The Dobe Ju/'Hoansi (Fourth ed.). Cengage Learning. p. 9. ISBN 9781133713531.

- ^ "General Questions". ǃKhwa ttu – San Education and Culture Centre. Retrieved 12 January 2014. Dieckmann, Ute (2007). "Shifting Identities". Haiom in the Etosha region: A History of Colonial Settlement, Ethnicity and Nature Conservation. Basel: Basler Afrika Bibliographien. pp. 300–302. ISBN 9783905758009.

- ^ Le Raux, Willemien (2000). "Torn Apart – A Report on the Educational Situation of San Children in Southern Africa". Kuru Development Trust and WIMSA. p. 2.

Although the people are also known by the names Bushmen and Basarwa, the term San was chosen as an inclusive group name for this report, since WIMSA representatives have decided to use it until such time as one representative name for all groups will be accepted by all.

- ^ a b c Hitchcock, Robert K.; Biesele, Megan. "San, Khwe, Basarwa, or Bushmen? Terminology, Identity, and Empowerment in Southern Africa". Kalahari Peoples Fund. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ^ a b Marshall, Leon (16 April 2003). "Africa's Bushmen May Get Rich From Diet-Drug Secret". National Geographic News. Archived from the original on 18 April 2003.

- ^ a b Wynberg, Rachel; Chennells, Roger (2009). "Green Diamonds of the South: An Overview of the San-Hoodia Case". Indigenous Peoples, Consent and Benefit Sharing Lessons from the San-Hoodia case. Dordrecht: Springer. p. 102. ISBN 9789048131235.

- ^ Suzman, James (2001). Regional Assessment of the Status of the San in Southern Africa (PDF). Windhoek: Legal Assistance Centre. pp. 3–4. ISBN 99916-765-3-8.

- ^ Marshall, Leon (16 April 2003). "Bushmen Driven From Ancestral Lands in Botswana". National Geographic News. Archived from the original on 18 April 2003.

- ^ "Basarwa Relocation – Introduction". Government of Botswana. Archived from the original on 9 April 2006.

- ^ "Ethnic Minorities and Indigenous Peoples". Ditshwanelo. The Botswana Centre for Human Rights. Archived from the original on 6 March 2014. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

- ^ Bennett, Bruce. "Botswana historical place names and terminology". Thuto.org. University of Botswana History Department. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

- ^ ZOONIMIA HISTÓRICO-COMPARATIVA BANTU: Os Cinco Grandes Herbívoros Africanos (PDF) (in Portuguese), Utrecht, Netherlands: Rhino Resource Center, 2013, retrieved 19 February 2016

- ^ Moran, Shane (2009). Representing Bushmen: South Africa and the Origin of Language. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press. p. 3. ISBN 9781580462945.

- ^ Anton, Donald K.; Shelton, Dinah L. (2011). Environmental Protection and Human Rights. Cambridge University Press. p. 640. ISBN 978-0-521-76638-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Anaya, James (2 June 2010). Addendum – The situation of indigenous peoples in Botswana (PDF) (Report). United Nations Human Rights Council. A/HRC/15/37/Add.2.

- ^ Smith, Malvern van Wyk (1 July 2009). The First Ethiopians: The image of Africa and Africans in the early Mediterranean world. NYU Press. ISBN 978-1-86814-834-9.

- ^ a b Mlambo, A. S. (2014). A history of Zimbabwe. Internet Archive. New York, NY : Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-02170-9.

- ^ Chirikure, Shadreck; Delius, Peter; Esterhuysen, Amanda; Hall, Simon; Lekgoathi, Sekibakiba; Maulaudzi, Maanda; Neluvhalani, Vele; Ntsoane, Otsile; Pearce, David (1 October 2015). Mapungubwe Reconsidered: A Living Legacy: Exploring Beyond the Rise and Decline of the Mapungubwe State. Real African Publishers Pty Ltd. ISBN 978-1-920655-06-8.

- ^ Godwin, Peter. "Southern Africa's hunter-gatherers seek a foothold". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 14 March 2016.

- ^ Connor, Steve (1 May 2009). "World's most ancient race traced in DNA study". The Independent.

- ^ a b Gill, Victoria (1 May 2009). "Africa's genetic secrets unlocked" (online edition). BBC World News. British Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 1 July 2009. Retrieved 3 September 2009.

- ^ Tishkoff, S. A.; Reed, F. A.; Friedlaender, F. R.; Ehret, C.; Ranciaro, A.; Froment, A.; Hirbo, J. B.; Awomoyi, A. A.; Bodo, J. -M.; Doumbo, O.; Ibrahim, M.; Juma, A. T.; Kotze, M. J.; Lema, G.; Moore, J. H.; Mortensen, H.; Nyambo, T. B.; Omar, S. A.; Powell, K.; Pretorius, G. S.; Smith, M. W.; Thera, M. A.; Wambebe, C.; Weber, J. L.; Williams, S. M. (2009). "The Genetic Structure and History of Africans and African Americans". Science. 324 (5930): 1035–44. Bibcode:2009Sci...324.1035T. doi:10.1126/science.1172257. PMC 2947357. PMID 19407144.

- ^ Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor. Botswana 2013 Human Rights Report (PDF). United States Department of State.

- ^ a b "San - Bushmen - Kalahari, South Africa..." www.krugerpark.co.za. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ Marjorie Shostak, 1983, Nisa: The Life and Words of a ǃKung Woman. New York: Vintage Books. Page 10.

- ^ Shostak 1983: 13

- ^ Shostak 1983: 9, 25

- ^ "The San people". 6 September 2017.

- ^ Brian Morris (2004). Insects and human life. Berg. p. 57. ISBN 978-1-84520-075-6.

- ^ Brian Morris (2005). Insects and Human Life, pp39-40. See page 19: for insect use in medicine, poison for arrows etc. Also page 188 regarding Kaggen, the Praying Mantis trickster deity who created the moon More on Kaggen, who might sabotage a hunt by transforming into a louse and biting the hunter: Mathias Georg Guenther (1999). Tricksters and Trancers: Bushman Religion and Society. p111.

- ^ "How San hunters use beetles to poison their arrows" Archived 3 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Biodiversity Explorer website

- ^ Earliest' evidence of modern human culture found, Nick Crumpton, BBC News, 31 July 2012

- ^ "World's Oldest Ritual Discovered -- Worshipped the Python 70,000 Years Ago".

- ^ "Ritual: Organised Activity Identified as World's Oldest". 6 March 2007.

- ^ "Afrol News - World's oldest religion discovered in Botswana".

- ^ "Stone Snake of South Africa: "first human worship" 70,000 years ago | Damien Marie AtHope".

- ^ "The modern day Bushmen / San" Archived 18 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Art of Africa. Retrieved 2012-01-29.

- ^ a b Knight, Alec; Underhill, Peter A.; Mortensen, Holly M.; Zhivotovsky, Lev A.; Lin, Alice A.; Henn, Brenna M.; Louis, Dorothy; Ruhlen, Merritt; Mountain, Joanna L. (2003). "African Y Chromosome and mtDNA Divergence Provides Insight into the History of Click Languages". Current Biology. 13 (6): 464–73. Bibcode:2003CBio...13..464K. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00130-1. PMID 12646128. S2CID 52862939.

- ^ Hammer, MF; Karafet, TM; Redd, AJ; Jarjanazi, H; Santachiara-Benerecetti, S; Soodyall, H; Zegura, SL (2001). "Hierarchical patterns of global human Y-chromosome diversity" (PDF). Molecular Biology and Evolution. 18 (7): 1189–203. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003906. PMID 11420360.

- ^ Naidoo, Thijessen; Schlebusch, Carina M; Makkan, Heeran; Patel, Pareen; Mahabeer, Rajeshree; Erasmus, Johannes C; Soodyall, Himla (2010). "Development of a single base extension method to resolve Y chromosome haplogroups in sub-Saharan African populations". Investigative Genetics. 1 (1): 6. doi:10.1186/2041-2223-1-6. PMC 2988483. PMID 21092339.

- ^ Chen, Yu-Sheng; Olckers, Antonel; Schurr, Theodore G.; Kogelnik, Andreas M.; Huoponen, Kirsi; Wallace, Douglas C. (2000). "MtDNA Variation in the South African Kung and Khwe—and Their Genetic Relationships to Other African Populations". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 66 (4): 1362–83. doi:10.1086/302848. PMC 1288201. PMID 10739760.

- ^ Tishkoff, S. A.; Gonder, M. K.; Henn, B. M.; Mortensen, H.; Knight, A.; Gignoux, C.; Fernandopulle, N.; Lema, G.; Nyambo, T. B.; Ramakrishnan, U.; Reed, F. A.; Mountain, J. L. (2007). "History of Click-Speaking Populations of Africa Inferred from mtDNA and Y Chromosome Genetic Variation". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 24 (10): 2180–95. doi:10.1093/molbev/msm155. PMID 17656633.

- ^ Schlebusch, Carina M.; Naidoo, Thijessen; Soodyall, Himla (2009). "SNaPshot minisequencing to resolve mitochondrial macro-haplogroups found in Africa". Electrophoresis. 30 (21): 3657–64. doi:10.1002/elps.200900197. PMID 19810027. S2CID 19515426.

- ^ Henn, Brenna; Gignoux, Christopher R.; Jobin, Matthew (2011). "Hunter-gatherer genomic diversity suggests a southern African origin for modern humans" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108 (13). National Academy of Sciences: 5154–62. doi:10.1073/pnas.1017511108. PMC 3069156. PMID 21383195.

- ^ Kaplan, Matt (2011). "Gene Study Challenges Human Origins in Eastern Africa". Scientific American. Nature Publishing Group. Retrieved 22 June 2012.

- ^ Rincon, Paul (24 April 2008). "Human line 'nearly split in two'". BBC News. Retrieved 31 December 2009.

- ^ Schlebusch, Carina M.; Skoglund, Pontus; Sjödin, Per; Gattepaille, Lucie M.; Hernandez, Dena; Jay, Flora; Li, Sen; De Jongh, Michael; Singleton, Andrew; Blum, Michael G. B.; Soodyall, Himla; Jakobsson, Mattias (19 October 2012). "Genomic Variation in Seven Khoe-San Groups Reveals Adaptation and Complex African History". Science. 338 (6105): 374–379. doi:10.1126/science.1227721. PMC 8978294.

- ^ Hitchcock, Robert K.; Babchuk, Wayne A. (2017), "Genocide of Khoekhoe and San Peoples of Southern Africa", Genocide of Indigenous Peoples, pp. 143–171, doi:10.4324/9780203790830-7, ISBN 9780203790830, retrieved 25 March 2023

- ^ Advisory Group on Forced Evictions, United Nations Human Settlements Programme (2007). Forced Evictions-- Towards Solutions?: Second Report of the Advisory Group on Forced Evictions to the Executive Director of UN-HABITAT. UN-HABITAT. p. 115. ISBN 978-92-1-131909-5.

- ^ "Botswana's bushmen get Kalahari lands back". CNN. 13 December 2006. Archived from the original on 20 December 2006. Retrieved 13 December 2006.

- ^ Kathleen Doheney, "Hoodia: Lots of Hoopla, Little Science; Few studies support the promise of the South African appetite suppressant, but believers abound", WebMD, September 6, 2006, Reviewed by Louise Chang, MD Retrieved March 24, 2007

- ^ Wynberg, R. (2005). "Rhetoric, Realism and Benefit-Sharing". The Journal of World Intellectual Property. 7 (6): 851–876. doi:10.1111/j.1747-1796.2004.tb00231.x.

- ^ Tully, S. (2003). "The Bonn Guidelines on Access to Genetic Resources and Benefit Sharing" (PDF). Review of European Community and International Environmental Law. 12: 84–98. doi:10.1111/1467-9388.00346.

- ^ Thomas, Elizabeth Marshall (2007). The Old Way: A Story of the First People. Macmillan. pp. xiii, 45–47. ISBN 9781429954518.

- ^ N!ai; Marshall, John; Marshall-Cabezas, Sue; Miesner, Adrienne; Mbulu, Letta (2004), N!ai: the story of a !Kung woman, Documentary Educational Resources (Firm), Public Broadcasting Associates, Documentary Educational Resources, retrieved 30 March 2024

- ^ "Reflecting on N!ai, The Story of a !Kung Woman". africa.harvard.edu. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ Kray, C. (1978) "Notes on 'Nǃai: The Story of a ǃKung Woman'" Archived 14 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine. RIT. n.d. Web. 5 October 2013.

- ^ Van Gelder, Lawrence (29 September 2000). "A Hunter's Story". The New York Times.

- ^ Attenborough, David (5 February 2003). "Human Mammal, Human Hunter (video)". The Life of Mammals. BBC. Archived from the original on 4 November 2021.

- ^ "How Art Made the World. Episodes . The Day Pictures Were Born. The San People of South Africa | PBS". www.pbs.org. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- ^ "Download How Art Made the World (Hardback) - Common ePub eBook @6B3B522E7DEEE17DDA23E86C6926E2F6.NMCOBERTURAS.COM.BR". 6b3b522e7deee17dda23e86c6926e2f6.nmcoberturas.com.br. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- ^ Nǃai, the Story of a ǃKung Woman. Documentary Educational Resources and Public Broadcasting Associates, 1980.

Bibliography

- Shostak, Marjorie (1983). Nisa: The Life and Words of a ǃKung Woman. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 0-7139-1486-6.

Further reading

- Gordon, Robert J. (1999). The Bushman Myth: The Making of a Namibian Underclass. Avalon. ISBN 0-8133-3581-7.

- Howell, Nancy (1979). Demography of the Dobe ǃKung. New York: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-357350-5.

- Lee, Richard; Irven DeVore (1999). Kalahari Hunter-Gatherers: Studies of the ǃKung San & Their Neighbors. iUniverse. ISBN 0-674-49980-8.

- Solomon, Anne (1997). "The myth of ritual origins? Ethnography, mythology and interpretation of San rock art". The Antiquity of Man. South African Archaeological Bulletin.

- Minkel, J. R. (1 December 2006). "Offerings to a Stone Snake Provide the Earliest Evidence of Religion". Scientific American. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

- Choi, Charles (21 September 2012). "African Hunter-Gatherers Are Offshoots of Earliest Human Split". LiveScience.

- San Spirituality: Roots, Expression,(2004) and Social Consequences, J. David Lewis-Williams, David G. Pearce, ISBN 978-0759104327

- Barnard, Alan. (1992): Hunters and Herders of Southern Africa. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521411882.

External links

- The site of the Khoisan Speakers

- ǃKhwa ttu – San Education and Culture Centre

- Kuru Family of Organisations

- South African San Institute

- Bradshaw Foundation – The San Bushmen of South Africa

- Cultural Survival – Botswana

- Cultural Survival – Namibia

- International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs – Africa

- Kalahari Peoples Fund

- Survival International – Bushmen