Ciudad Bolívar

Ciudad Bolívar Angostura | |

|---|---|

City | |

| Ciudad Bolívar | |

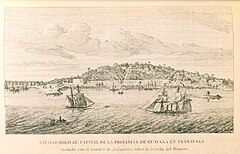

Top:Panoramic view of Ciudad Bolivar, Orinoco River and Angostura Bridge, from Paseo Meneses area, Second:Angostura Regional Congress, Llovizna Falls, (left to right) Third:Bolivar Square and Ciudad Bolivar St. Thomas Cathedral, (both photos) Bottom:An overview of downtown Casco Historico and Orinoco River area | |

| Nickname(s): La puerta del sur de Venezuela (English:"The gate to southern Venezuela") | |

| Motto(s): No encontrarás otra de más variada riqueza (English:"You won't find another with such a variety of wealth")[1] | |

Municipal borders in the state of Bolívar | |

| Coordinates: 8°08′17″N 63°32′54″W / 8.137930°N 63.548266°W | |

| Country | |

| State | Bolívar |

| Municipality | Heres |

| Founded | 22 May 1764 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Sergio Hernández (PSUV)[1][3] |

| Area | |

• Total | 209.52 km2 (80.90 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 54 m (177 ft) |

| Population (2022) | |

• Total | 422,578[2] |

| • Density | 1,633.63/km2 (4,231.1/sq mi) |

| • Demonym | Bolivarense |

| Time zone | UTC−4 (VET) |

| Postal code | 8001 |

| Area code | 0285 |

| Climate | Aw |

| Website | Official Site. |

| The area and population figures are for the city. | |

Ciudad Bolívar (Spanish pronunciation: [sjuˈðað βoˈliβaɾ]; Spanish for "Bolivar City"), formerly known as Angostura[4] and St. Thomas de Guyana,[5] is the capital of Venezuela's southeastern Bolívar State. It lies at the spot where the Orinoco River narrows to about 1 mile (1.6 km) in width, is the site of the first bridge across the river, and is a major riverport for the eastern regions of Venezuela.

Historic Angostura gave its name to the Congress of Angostura, to the Angostura tree, to the House of Angostura, and to Angostura bitters. Modern Ciudad Bolívar has a well-preserved historic center; a cathedral and other original colonial buildings surround the Plaza Bolívar.

History

Originally a Spanish settlement, it was called Santo Tomé de Guayana (Saint Thomas of Guyana). The settlement was a fortified port which had to be moved on three occasions because it was constantly attacked by Carib natives and European rivals, such as the Dutch and English.[6]

In 1576 Saint Thomas of Guyana was first located in present-day Ciudad Guayana by missionaries near the Caroní River until Dutch forces led by Captain Adrian Janson destroyed the town in 1579.[6] The second settlement was founded by Don Antonio de Berrío in 1595, who had arrived from the New Granada with the mission of colonizing Guiana, and was moved westward down the Carońi about 66 kilometres (41 mi).[6] One of Walter Raleigh's expeditions sacked the second settlement in 1617, resulting in the death of his son Watt Raleigh.[6][7]

Fernando de Berrio was present on March 11, 1619 in the destroyed Saint Thomas of Guyana with the credentials granted by the Royal Audience of Santa Fe, just a few months after the decapitation of Raleigh in 1618.

The first task was the reconstruction of Saint Thomas of Guyana on the sides of Chirica, a more defensible and suitable place for tobacco cultivation. Berrio commissioned Captain Jerónimo de Grados and Alonso de Monteros to recruit indigenous in the Esequibo River, but they were captured by British pirates for whose freedom they intended to collect a ransom translated into a few quintals of tobacco in branch. Finally Saint Thomas of Guyana was refounded by Fernando de Berrio in 1620.

In 1629, English and Dutch pirates, under the command of Adrian Jansz Pater, attacked and destroyed Saint Thomas of Guyana and afterwards fortified themselves in the branches and creeks of the Orinoco River.

In 1637 the Dutch, settled at the mouths of the Amakura, Essequibo and Berbice, again attacked and burned Saint Thomas of Guyana and raided Trinidad.

The fourth and present day city was officially founded in 1764 by Don Joaquin Moreno de Mendoza as San Tomas de la Nueva Guayana,[6][8] Santo Tomé de Guayana de Angostura del Orinoco, or San Tomé de Angostura,[9] named in honor of its diocese and for its position at the first narrows of the Orinoco River. The Spanish relied on trade from the Dutch colony of Essequibo further down the Caroní River until 1771.[6]

Angostura was the capital of Guayana Province and the site of the Congress of Angostura from 1819 to 1821. It was responsible for the creation of Gran Colombia in its first year of operation.[8] Angostura bitters were invented in the city in 1824, although the company which produced them later moved to Trinidad and Tobago.[10]

The city was renamed in honor of Simon Bolivar in 1846.

The Venezuelan artist Jesús Rafael Soto was a native of the city. The Jesús Soto Museum of Modern Art, named in his honor and designed by Venezuelan architect Carlos Raúl Villanueva, was opened in 1973.

Law and government

Ciudad Bolívar's municipal government is led by the mayor. Its local legislature is the Municipal Council, made up of seven councillors. A municipal comptroller oversees the public finances, and the Local Public Planning Council manages the municipality's development.[11]

Geography

Vegetation

Moriche palms and scrub oaks are found on the shores of the river. Species including the carob tree, the sarrapia (tonka bean), and the merecure are prevalent. Local fauna include capybaras, turtles, herons, parrots, limpets, and iguanas, and others. Fish in the area include Salminus hilarii (a species of Salminus) and Pygocentrus palometa.

Climate

Under the Köppen climate classification, Ciudad Bolívar has a tropical savanna climate (Aw) with distinctive dry and wet seasons. The average temperature is 28.5 °C (83.3 °F) which remains fairly constant throughout the year, varying between 27.6 °C (81.7 °F) in January to 28.9 °C (84.0 °F) in October. The dry season, which runs from December to April has little precipitation during these months and temperatures tend to be cooler than the wet season but still hot, regularly reaching 32 °C (90 °F) during the day and dropping to 22 °C (72 °F) during the night. The wet season which runs from May to early November sees and increase in precipitation levels although days without any precipitation are common. Temperatures tend to be slightly warmer than the dry season. On average, Ciudad Bolívar receives 977 mm (38.5 in) of precipitation per year and there are 89.3 days with measureable rainfall. The city is fairly sunny, averaging almost 2900 hours of bright sunshine or an average of 7.9 hours of sunshine per day, ranging from a high of 260.4 hours in October (8.4 hours of sunshine per day) to a low of 201.0 hours in June (or 6.7 hours of sunshine per day).[12]

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Record high °C (°F) | 39.9 (103.8) |

39.8 (103.6) |

39.5 (103.1) |

39.7 (103.5) |

40.4 (104.7) |

37.4 (99.3) |

38.2 (100.8) |

37.6 (99.7) |

39.7 (103.5) |

37.9 (100.2) |

38.2 (100.8) |

37.6 (99.7) |

40.4 (104.7) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 32.8 (91.0) |

33.9 (93.0) |

35.0 (95.0) |

35.4 (95.7) |

34.6 (94.3) |

32.9 (91.2) |

32.2 (90.0) |

32.5 (90.5) |

33.4 (92.1) |

33.5 (92.3) |

33.0 (91.4) |

32.4 (90.3) |

33.5 (92.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 26.4 (79.5) |

27.3 (81.1) |

28.4 (83.1) |

29.6 (85.3) |

29.0 (84.2) |

27.4 (81.3) |

26.8 (80.2) |

27.0 (80.6) |

27.4 (81.3) |

27.8 (82.0) |

27.3 (81.1) |

26.5 (79.7) |

27.6 (81.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 22.7 (72.9) |

23.0 (73.4) |

23.7 (74.7) |

24.7 (76.5) |

24.9 (76.8) |

24.4 (75.9) |

24.0 (75.2) |

24.1 (75.4) |

24.5 (76.1) |

24.5 (76.1) |

24.2 (75.6) |

23.3 (73.9) |

24.0 (75.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 17.5 (63.5) |

18.1 (64.6) |

20.0 (68.0) |

12.8 (55.0) |

17.7 (63.9) |

18.2 (64.8) |

18.2 (64.8) |

17.8 (64.0) |

18.0 (64.4) |

18.5 (65.3) |

19.2 (66.6) |

18.0 (64.4) |

12.8 (55.0) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 40.1 (1.58) |

16.5 (0.65) |

22.8 (0.90) |

30.7 (1.21) |

116.0 (4.57) |

284.2 (11.19) |

255.0 (10.04) |

251.5 (9.90) |

120.7 (4.75) |

131.0 (5.16) |

125.1 (4.93) |

80.3 (3.16) |

1,473.9 (58.03) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 4.8 | 2.6 | 2.2 | 2.9 | 8.8 | 14.3 | 15.0 | 13.7 | 8.5 | 8.9 | 8.5 | 7.0 | 97.2 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 69.5 | 67.5 | 66.0 | 66.5 | 69.5 | 73.5 | 73.5 | 72.5 | 70.5 | 71.0 | 71.5 | 72.0 | 70.2 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 248.0 | 235.2 | 263.5 | 234.0 | 226.3 | 201.0 | 232.5 | 248.0 | 252.0 | 260.4 | 249.0 | 244.9 | 2,894.8 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 8.0 | 8.4 | 8.5 | 7.8 | 7.3 | 6.7 | 7.5 | 8.0 | 8.4 | 8.4 | 8.3 | 7.9 | 7.9 |

| Source 1: NOAA (sun 1971–1990)[13][12] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Instituto Nacional de Meteorología e Hidrología (humidity 1970–1998)[14][15] | |||||||||||||

Economy

The Bolívar state economy is dominated by agriculture and animal husbandry, particularly cattle and pigs. Agricultural products of the area include maize, cassava, mango, yam, and watermelon. Tourism has become increasingly important to the area.

Local mass media include the television stations Bolívar Visión and TV Río, and newspapers El Bolivarense, El Expreso, El Progreso, and El Luchador.

Education

Universities

Universidad de Oriente

Universidad de Oriente (UDO) Núcleo de Bolívar, is the main public institution located in Ciudad Bolivar and in other cities of eastern Venezuela. On 20 February 1960, by resolution of the University Council, is created the Bolívar Nucleus, since that is become the most important university in the country South-Eastern.

Today, this UDO nucleus has a Basic Courses School, Health Sciences School "Dr. Francisco Battistini Casalta" and Earth Sciences School, undergraduate degrees in Industrial Engineering, Geological Engineering, Civil Engineering, Mining Engineering, Geology, Medicine, Nursing and Bioanalysis.[16]

Universidad Nacional Experimental de Guayana

Universidad Nacional Experimental de Guayana (UNEG) is another public institution in Ciudad Bolívar, founded 9 March 1982 by resolution N° 1.432 of President Luis Herrera Campins. This university was conceived as a center of superior regional education.

The original name of the university project was South University the Dr. Carlos Grüber Hernández (1931–2007) cas one of the pioneers in the fight for the University of South, he was the Founder President of the University of Southern Pro Guiana Committee.[17]

The UNEG Ciudad Bolívar offers undergraduate degrees in Administration and accounting, Education and Tourism.

Other universities

- Universidad Simón Rodríguez.

- Universidad Gran Mariscal de Ayacucho.

- Instituto Universitario Tecnológico del Estado Bolívar.

- Universidad Nacional Abierta.

- Instituto Universitario Tecnológico Rodolfo Loero Arismendi.

- Universidad Bolivariana de Venezuela.

- Instituto Universitario de Tecnológia Antonio José de Sucre.

- Universidad Nacional Experimental Politécnica de la Fuerza Armada Nacional.

- Universidad Pedagógica Experimental Libertador.

- Universidad Central de Venezuela (UCV) – Centro Regional Ciudad Bolívar

Culture

Ciudad Bolívar's historic district is a popular tourist attraction, featuring houses and buildings that date from the colonial period. The Jesús Soto Museum of Modern Art—named after the city's native sculptor and painter Jesús Soto—features a collection of modern works by Venezuelan and international artists. Ciudad Bolívar is also the birthplace of musicians Antonio Lauro, Cheo Hurtado, Iván Pérez Rossi, and the home of the musical group Serenata Guayanesa.

Traditional local cuisine includes desserts and preserves made of cashew nuts, eaten alone or roasted with salt. The cassava bread prepared in the area is well known, as well as several meals made of tortoise meat such as the Carapacho de Morrocoy Guayanés (baked tortoise in its shell). Locals also use the juice of cassava to create the spicy Catara sauce, an alleged aphrodisiac.

Gallery Images

- Bolívar Square

- Botanic Garden in Ciudad Bolívar

- Colonial style in Ciudad Bolívar

- Typical street in Ciudad Bolívar

Transportation

Buses are the main means of public transport in the city.

The José Tomás de Heres Airport is located in the center of the city.

The Angostura Bridge connects the city to the rest of Venezuela. The freeway that connects Ciudad Bolívar with Ciudad Guayana is a major regional road.

Notable people

- Darwinzon Hernandez (1996), Major League Baseball pitcher for the Boston Redsox

- Luz Machado (1916–1999), poet. Awarded with the National Prize for Literature in 1987.

- Antonio Lauro (1917–1986), guitarist and composer. considered to be one of the foremost South American composers for the guitar in the 20th century.

- Pompeyo Márquez (1922-2017), politician and former marxist guerrilla member in the 1960s. He was one of the founders of the party Movimiento al Socialismo in 1971.

- Jesús Soto (1923–2005), op and kinetic artist, a sculptor and a painter.

- Luis García Morales (1929–2015), poet and cultural promoter.

- Milka Chulina (1974), Miss Venezuela 1993 and 2nd Runner-up in Miss Universe 1993

- Victor Martinez (1978), first Baseman/Catcher/Designated Hitter for the Detroit Tigers of Major League Baseball.

- Iván Pérez Rossi (1943), singer and composer. Founder of the folk group Serenata Guayanesa.

- Gustavo Rodríguez (1947–2014), film, stage and television actor.

- Cheo Hurtado (1960), virtuoso performer of the cuatro.

- Rubén Limardo (1985), fencer. Olympic gold medalist in London 2012.

- Carlos Mendoza, Major League Baseball outfielder and coach

- Rafael Antonio Curra (1934-1968), marine biologist, director of the Oceanographic Institute of Venezuela (1967-1968).

See also

References

Citations

- ^ a b "Alcaldía Bolivariana del Municipio Heres". Archived from the original on 17 May 2014. Retrieved 22 May 2014.

- ^ "Ciudad Bolivar Population 2024".

- ^ Partido Socialista Unido de Venezuela

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 401.

- ^ Cotton, Henry (1831). A Typographical Gazetteer. Oxford University. p. 113.

Guyana, or St. Thomas de Guyana, also called Angostura, the capital of the province of Spanish Guyana in South America, is a considerable town, seated on the river Oroonoko, not far from its mouth.

- ^ a b c d e f "Alexander von Humboldt, Personal Narrative of Travels to the Equinoctial Regions of America During the Years 1799–1804, (chapter 25). Henry G. Bohn, London, 1853". Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- ^ John Hemming, The Search For El Dorado, Phoenix Press; 2nd ed. 31 December 2001; Ch. 10. ISBN 1842124455

- ^ a b EB (1878).

- ^ Lavaysse, Jean-J. Dauxion (1820). A statistical, commercial, and political description of Venezuela, Trinidad, Margarita, and Tobago. G. and W.B. Whittaker. p. 128.

- ^ Loeb, Katie M. (2012). Shake, Stir, Pour: Fresh Homegrown Cocktails. Beverly, MA: Quarry Books. p. 146. ISBN 9781592537976. OCLC 806490659.

- ^ Law and government Archived 15 November 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Ciudad Bolivar Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 10 February 2024. Retrieved 9 February 2024.

- ^ "Ciudad Bolivar Climate Normals 1991–2020". World Meteorological Organization Climatological Standard Normals (1991–2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 10 February 2024. Retrieved 9 February 2024.

- ^ "Estadísticos Básicos Temperaturas y Humedades Relativas Máximas y Mínimas Medias" (PDF). INAMEH (in Spanish). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 June 2013. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ^ "Estadísticos Básicos Temperaturas y Humedades Relativas Medias" (PDF). INAMEH (in Spanish). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 June 2013. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ^ "Universidad de Oriente - Núcleo de Bolivar". Archived from the original on 26 June 2014. Retrieved 22 May 2014.

- ^ El Expreso Foro de los Lunes "Anhelo de la Colectividad. Creación de la Universidad de Guayana" pag.3 Ciudad Bolívar 17 December 1979

Bibliography

- , Encyclopædia Britannica, vol. II (9th ed.), New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1878, p. 45.

External links

Ciudad Bolívar travel guide from Wikivoyage

Ciudad Bolívar travel guide from Wikivoyage- Bolívar's message to the Congress of Angostura Archived 11 December 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Ciudad Bolívar at Venezuelatuya.com (in Spanish)

- Images of Ciudad Bolívar (in Spanish)