SS Willem III

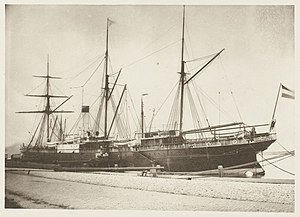

SS Willem III in Nieuwe Diep (Den Helder) | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | SS Willem III |

| Owner | Stoomvaart Maatschappij Nederland |

| Ordered | May 1870[1] |

| Cost | 900,000 guilders[1] |

| Yard number | 132[1] |

| Laid down | 1870 |

| Launched | 8 March 1871[1] |

| Out of service | 19 May 1871 |

| Renamed | 1872 Ravensbourne (temporary) |

| History | |

| Name | Quang Se |

| Owner | Wm. Houston, J.A. Steel |

| Acquired | 1873 |

| History | |

| Name | Glenorchy (at first Quang Se) |

| Owner | Glen Line |

| Acquired | 1875 |

| Renamed | Glenorchy, 1877 |

| History | |

| Name | Pina |

| Owner | G.H. Lavarello |

| Acquired | January 1898 |

| Fate | Sold for scrap, July 1903[1] |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Passenger liner[1] |

| Tonnage | 2,600 GRT[1] |

| Displacement |

|

| Length | 320 ft 0 in (97.5 m)[1] |

| Beam | 39 ft 0 in (11.9 m)[1] |

| Draught |

|

| Installed power | 1,600 ihp (1,200 kW)[1] |

| Propulsion | Single screw |

| Sail plan | 3-masted barque |

| Speed |

|

| Complement | 90 |

SS Willem III was the lead ship of the Willem III class, and the first ship of the Stoomvaart Maatschappij Nederland (SMN). She was burnt on her maiden trip. Later the wreck was repaired and sailed as Quang Se, Glenorchy and Pina.

Context

Steamships for the Suez Canal

SS Willem III was the lead ship of the Willem III class, and the first ship built for Stoomvaart Maatschappij Nederland (SMN). The SMN was founded in May 1870 for the express purpose of establishing a steam shipping line to Java via the Suez Canal, which opened in 1869. This would require steamships of a 'new' type.

Before construction of the Suez Canal started in 1859, steamships were not economical in communication with the far east. The basic problem was that steaming the long distance around Cape of Good Hope consumed so much coal that if a ship carried enough coal, it did not have enough cargo space left to make a profit. Coal could be loaded en route, but bunkering took so much time that most of the advantage in speed would then be lost. During the 10 years that the canal was constructed, developments in steam power went ahead. A crucial development was the compound engine suitable for use in salt water. The compound engine reduced coal consumption by nearly 50%. It would give the steamship a definite lead on the sailing ship, which could not reliably use the Suez Canal. However, the small number of existing ships with compound engines, meant that in practice a shipping line that wanted to use the canal had to buy new ships.

Stoomvaart Maatschappij Nederland

The Stoomvaart Maatschappij Nederland was founded 1869-1870. It got some guarantees for cargo from the state, but one of the conditions was that its first ship had to leave for the Indies at a certain date. This would become 15 May 1871. It was one of the reasons why the selection of a ship type and builder was one of the first tasks of the SMN. The choice for John, Elder & Co was very likely, because C.J. Viehoff was closely involved in founding the SMN. Viehoff was a continental representative for John, Elder & Co. He even became one of the executive members of SMN's first board, and then quit as representative of John, Elder & Co.[3] One can assume that Viehoff profited from the deal with John, Elder & Co. One can also safely assume that the other founders somehow wanted to profit.

After the SMN had been founded Boissevain and Viehoff traveled to Glasgow to finalize the order. The final bidding would take place between four major shipbuilders on the Clyde. John, Elder & Co was said to have won this order on terms and price. The final delivery term of Willem III was set on 1 April 1871. It was a term of 11 months and this was very short at the time.[4] From the fact that only shipbuilders on the Clyde were invited to this tender, one can assume that it took place during the stay of Boissevain and Viehoff in Glasgow. This might have caused a delay that put severe pressure on the construction and delivery of Willem III, so that she could sail on 15 May 1871.

Characteristics

Dimensions

SS Willem III was 320 feet long, 39 feet wide and had a draught of 21 feet 2 inches. The cargo size of the ship was 2,600 tons GT.[1] Tideman has general data about Prins van Oranje, which can be assumed to be identical to Willem III: 97.53 m from bow to stern. Beam 11.96 m external. Depth of hold 9.775 m. Draught 6.7 m. .[5]

Machinery

The compound steam engines were also delivered by the shipyard. They were of the improved Wolf system[6] of nominal 400 hp, effective 1,600 ihp. They were said to consume only 20 tons of coal a day.[7] As Quang Se she had a screw of the Hirch system.[8]

Accommodation

There was accommodation for 90 passengers first class, and 30 passengers second class.[9] For the passengers the first class saloon was the luxurious center of the ship. Here up to 70 people could have dinner and other meals. There were also a ladies room, a children's room and a library. The smoking lounge was the place where smoking was permitted. The passenger cabins were for 2-4 persons.[7] On the return trip first class A cabins for two persons cost 1200 guilders per adult passenger. First class B cabins were for four persons and would cost 900 guilders per adult. In all other respects first class A and B were the same. Second class passengers would pay 500 guilders on the return trip.

There were also ice-rooms, a butchery, a map room, a pharmacy, a pantry with equipment to heat 1,600 plates, a buffet, a fruit storage, general food storage, a 'cellar' for beer, wine and liquors, a dessert room. On deck were some sheds for livestock and for four cows.[6]

Complement

The crew of Willem III consisted of 90 persons. A captain, four officers, a medic, 25 non commanding officers and sailors, 4 engineers with 21 assistants and firemen. The non-sailing staff consisted of an administrator and 27-29 male and female servants.[9] The crew uniform was of blue broadcloth with silver linings.[6]

Service

Construction

SS Willem III was built for Stoomvaart Maatschappij Nederland (SMN) by John Elder & Co. of Govan on the River Clyde. She was launched on 8 March 1871. At that time she was expected to leave Nieuwdiep under Captain E. Oort for Batavia on 15 May.[10] Some time later, on 3 May 1871, Willem III made her trials, and was to leave for Nieuwediep shortly after.[11] On Thursday 4 May at 7 o'clock in the evening Willem III left Greenock for Nieuwediep.[12]

In Nieuwediep

On 8 May 1871 Willem III arrived in Texel.[13] That same morning entered Niewediep, where she unloaded 332 tons of coal.[9]

The departure to the Dutch East Indies was planned for 15 May. It meant that a lot had to be done in Nieuwediep. A large number of small ships arrived to transfer cargo. Loading was done hastily, with quite some cargo getting damaged.

Meanwhile many people wanted to visit the ship. An extra train to Den Helder was planned for the visitors on Sunday 14 May. Many steam vessels also brought spectators. That day the flag was hoisted on many buildings in Nieuwediep. From 12 till 4 o'clock in the afternoon visitors could see almost the whole ship. After the visits the board of the SMN gave a big dinner on board ship. In the evening fireworks depicted the ship. These were followed by a ball that lasted till the next morning. Prince Henry meanwhile arrived in Den Helder with the last train.[14] In the early morning of 15 May Prince Hendrik arrived on board and had lunch.

A detachment of extra troops for the Indies was planned to sail on Willem III. It were 125 men commanded by Captain N.J.H. van Heijningen, lieutenants 2nd class O.F.W.F. Von Lindenfels, E.K.A. de Neve and H. Ovink, as well as medical officer L. Ritsema.[15] By 11 May the plan was that this detachment would leave Harderwijk on 15 May, and embark on Willem III the same day,[16] but this kind of contradicts departure of the ship on that day.

Delayed departure

On 15 May the planned departure of Willem III did not take place. According to some this was caused by the government insisting on an inspection of the steam engines, even though these had already been certified in England.[17] In the evening of 15 May the detachment of soldiers arrived in Nieuwediep.[18] It's not known whether this prevented departure the same evening. What is known is that loading continued on Tuesday evening.

Whatever the cause of the delay, Willem III steamed out of Nieuwediep on Wednesday 17 May at noon. She then anchored before the harbor to adjust the compasses.[19] On Thursday 18 May at half past seven in the evening Willem III left Nieuwediep for Batavia. On board were 69 passengers, 125 soldiers and a precious cargo.[20]

Passengers were pleased with how little the ship vibrated, and had a pleasant evening getting to know each other that first evening. On Friday things seemed very hopeful; the ship had cruised at 10 knots and people were calculating when they would see Gibraltar. One of the passengers of first class B (four person cabins) had complained about a steam pipe running near the bed of his child. It was not isolated and had gotten so warm at night that his child could not remain in its bed. The captain had seen to it, and the passenger hoped that it would be better. In the ladies bathroom much steam had been observed, but the ladies were told that the engineer had already taken care of it.[21]

Burned near Southampton

In the evening of Friday 19 May 1871 Willem III was steaming in fair weather in the English Channel. At about nine o'clock in the evening the children were put to bed, and some passengers followed this example. One passenger, Mrs Pabst and her four children remained on deck for a very long time. She told other passengers that one of the steam pipes in her cabin produced an unbearable heat in her cabin.[22]

Other passengers had gone to the saloon, where some ladies made music, and the gentlemen played cards. Shortly before 10 o'clock Mrs Pabst also joined the ladies in the saloon.[23] Willem III then reached a position between the longitudes of Isle of Portland and Wight, about 20 English miles from Ventnor.[21]

At about 10 o'clock passengers walking on deck then heard someone yelling 'fire', and so did the people in the saloon. It was followed by general pandemonium. Parents rushed towards their children and goods. The captain and officers rushed forward to investigate and organize fire fighting.[21] It was found that one of the first class passenger cabins near the bow had caught fire. Four children sleeping there were quickly saved by some men. The fire spread so quickly that attempts to quench it failed. After a short time frame sailors started to bring lifebuoys on deck, and the seriousness of the situation became clear. Nothing could be saved. The heavy smoke prevented passengers from reaching their cabins, and the same applied to the crew. Many passengers were only partly clothed, and many children had only blankets.

The captain then gave orders to ready the boats. There was quite some trouble to get the boats from the deck and to the waterside. They were heavy and new, and the crew had only been on board for three days. Now the soldiers played a key role in getting the boats in position.[24] Later witnesses would declare that it was only the large number of available hands that made it possible to get the boats into the water.[25] Many frightened passengers threw themselves in the boats, while they were still on board. It caused that they had to be vacated again, and so precious time was lost.[26] However, order was restored.

Now the first boat was designated for women and children, and was lowered into the water. As many women and children as possible were let in. Due to the water rising in this life boat, one quickly realized that the plug had not been put in, but this problem was quickly solved. Five more boats were lowered into the water, and filled with male passengers, some of the soldiers and some crew to manage them.[21] During this process some navy officers on board were said to have been essential in preventing accidents from happening to the frightened passengers. These were Captain Pieter van der Velden Erdbrink, lieutenant 2nd class M.J.C. Lucardie, W.F. Wesselink, and H.H.J. Kempe, who took the lead of the separate lifeboats.[27]

Nevertheless, most of the troops could not be fit in the boats, because some of these left while not yet full. Therefore many soldiers had to remain on board the burning ship, but they retained discipline under the command of their officers. It was sheer luck that there was almost no wind. The boats were floating on a calm sea. They had almost no oars, and would have been in big trouble if the sea became rougher.[21]

Rescue

At half past in the night the shipwrecks saw a cutter sailing towards them. She turned out to be the English pilot cutter Mary from Portsmouth, a vessel of only 24 ton, about 1% of the size of Willem III. She was commanded by skipper John Coote, a Trinity House pilot of Owers station. On Friday night at about 10 o'clock she was south west of Owers Lightship, when she saw a quick succession of white, red and blue fire eight miles to the south. It was a clearly a distress signal from a ship. With only a light north west wind Mary steered towards the distress signal, repeatedly answering with the ordinary pilot signal. Because the wind was so light, the cutter put out a boat with two rowers to make more speed. For more than an hour the boat pulled her till they reached the place from whence the signals had been given. Here the crew saw a big ship burning from bow to stern. Small lights were seen around the ship, and on approaching these proved to be the lanterns of lifeboats.[28]

On seeing Mary at about half past one, two lifeboats rowed towards her as best as they could. The passengers of these boats were transferred to the small cutter, which had to remain at a respectable distance, because there was ammunition on board Willem III. The two boats immediately rowed back to the burning ship, and succeeded in getting the remaining soldiers and crew from the ship.[21] Mary would take 114 people on board, of which 48 soldiers, their officers with their families, and 20 women and 12 children.

Other lifeboats rowed towards a French schooner which arrived somewhat later. This was the galiot Flora, commanded by A. Aubriët.[29] Aubriët was reported first to have asked whether the shipwrecked were Germans, before giving assistance. The schooner took some of the shipwrecked on board. A passenger noted the time as 10 minutes to two, and explosions were heard.[30]

Still somewhat later the screw steamship Scorpio of the Sunderland Charente line also arrived. She took the crew and the soldiers on board (probably those that had stayed behind on the burning ship), as well as those passengers that were on board the schooner, and transported 134 people to Portsmouth, where they arrived about 10 o'clock.[31][21] Another pilot cutter, Alarm of skipper Greenham also arrived and lent a pilot to Scorpio so she could steam to Spithead. The sailing vessel Mary would only arrive in Portsmouth at about 2 PM.[21]

The wreck is towed to Portsmouth

Cambria, a London tugboat arrived from the lookout point St Catherine's Point, and took the burning ship in tow. Cambria and Willem III arrived at Spithead on Saturday 20 May about noon. Here the burning ship was put high on a shoal between Spithead and the entrance of Portsmouth harbor.[32] The naval director of Portsmouth, Sir James Hope took charge of attempts to save some of the ship. Command Captain Moriarty C.B., harbormaster of Portsmouth served under his command. Attempts were made to quench the fire by making holes in the hull, but even this extreme measure did not help much. The harbor tugboats Camel and Pelter were engaged, and so were the steam fireboats of the harbor, which put an enormous amount of water on the ship. Extinguishing the fire was not easy because at the time the mass of coal on board was burning. Afterwards the hull above the waterline was bent in the strangest ways, and the inside of the ship was a chaos of entangled iron.[28]

By six o'clock in the morning (or evening of Saturday), Captain Oort reported that the ship had burned down to the waterline and was still burning. By 10 o'clock she was reported as 'burning, crew and passengers are safe'. One still hoped to save the shipment of money (worth 18,000 GBP[24]) that was on board.[33] This would indeed happen.[21]

Aftermath

Reception in Portsmouth

While there were many statements that the shipwrecked were warmly received in Portsmouth, there were also complaints. These centered in particular on the Dutch consul in Portsmouth.[34] Members of the first chamber of the house of representatives asked the government for an investigation of his behavior.

The Soldiers

After the soldiers arrived on shore they were reviewed on the terrain opposite the office of the Dutch Consul Mr. van den Bergh. They were as they had left the ship, many of them only partly clothed. They were nevertheless in a good mood, their hurrahs sounded loudly when their officers appeared in front. The same happened when some women and children from the ship, also only partly dressed, passed them by. Lt-General Templetown ordered the soldiers to be quartered in the Anglesea Barracks at Portsea. The event gave the locals a favorable impression of these soldiers.[28] On 23 May the paddle-steam Valk left Nieuwediep to collect these troops, but this was not the end of their story. On 23 May the paddle-steamer Valk commander Clifford Kock van Breugel left Nieuwdiep to collect them.

The soldiers arrived back in Harderwijk in an awful collection of garments, including English uniforms. Many Dutchmen called for doing something for these men, who had lost all their possessions. On 5 June the king thanked the soldiers and officers for their behavior during the disaster in an official order. Now a collection was started for the soldiers and non-commanding officers. Their loss was estimated at 4,631 guilders. In the end 2596.37 guilders were raised to distribute among the soldiers and non-commanding officers.[35] They would again sail to the Indies on 1 July on board the barque Noach III captain L. Hoefman. Of the officers Van Heyningen and De Neve would again command the detachment. On 19 June 1871 Van Heyningen was appointed as knight in the Order of the Netherlands Lion On Saturday 1 July the detachment arrived in Rotterdam by train. It was welcomed by officers and music from the local militia. The soldiers then marched to the 'Boompjes' where they embarked on Noach III. On board they were welcomed by a number of civilians and Fop Smit Jr, owner of the ship. Fop Smit made a speech and so did one of the officers of the militia. The commander made a suitable reply, and the small ceremony was rounded off with some drinks. On 27 September the soldiers arrived in Batavia.

Salvaging the cargo

On 4 June 1871 an attempt was made to lift Willem III from the bank by using pumps and tugboats, but the hull was so leaky that the attempt failed.[36] On Sunday 11 June Willem III was finally refloated, and she was towed into Portsmouth on Monday 12 June.[37] Here some cargo which had only been damaged by water was unloaded, among it 27 numbered chests. By 17 June 256 pieces of cargo had been unloaded. Later a list of 299 marked and numbered pieces was sent to Amsterdam. Still later about a 1,000 pieces of cargo were salvaged. It proved that the goods stored below the water line had suffered comparatively lightly. Most of the goods were then auctioned for about 5,000 GBP,[38] or 60,000 guilders. On 1 August the rewards for the salvage attempts were determined by the Admiralty court. Skipper Greenham was awarded 240 guilders, and 60 for expenses. The cutter Mary got 7,200 guilders. Scorpio got 12,000 guilders, Cambria 30,000 guilders.[39]

Inquiry

The SMN appointed a commission of inquiry after the disaster. Originally it consisted of the directors Julius G. Bunge, J.E. Cornelissen, C.A. Crommelin and from the supervisory board: C.J.A. den Tex and A.R.J. Cramerus. During the first regular shareholder meeting of the SMN on 30 May, Mr Mees and Mr Plate from Rotterdam pressed for an independent commission of experts, even stating that these should not be from Amsterdam, saying that otherwise the public would not deem the commission independent.[40] The board reacted by including two experts: Captain-lt N.M.J. Kroef and P. Buijs of the society of Dutch insurers. Later Buijs resigned again because many Dutch insurers were party to resolving the damage.[41]

The report of the commission[42] was published in December 1871.[43] It contains witness statements of most of the people involved, describing the event in much more detail. Major findings were that the fire probably originated somewhere in the cargo hold. Many witnesses sought the probable cause in the haste with which the ship was carelessly loaded in Nieuwediep. Many witnesses observed smoking on board during loading. Windmatches were also found on board. The pipe running through the cabin of Major Pabst was not deemed to have caused the fire, but its exact relation to the fire did not become clear.

As regards the safety measures, it became clear that it was sheer luck that nobody had been killed in the fire. The safety means, like fire fighting tools were found to have been quite good, and the quality of the lifeboats was deemed very good. On the contrary the general preparedness of the crew was below any standard. Nobody knew where the keys to the chests that contained the emergency signals were. These had to be forced till somebody found the chest with the skyrockets. Nobody had had the time to investigate the cannon, and so only one or two shots were fired, way after the fire had started.

With regard to the lifeboats it was the presence of the soldiers that meant that these could be launched at all. A division of the passengers and crew over the seven lifeboats had not been made. The boats could contain 340 persons, enough space for the 306 persons on board. For all persons to fit in the boats, it was crucial that all boats were loaded to almost maximum capacity, but some lifeboats distanced themselves from the ship when they were not at all full. The result was that many of the soldiers were left on board when there was room in the boats. The accidental presence of some naval officers that took command of the boats saw that some of the boats stayed with the ship. It probably saved those left on board.

The commission stated that she had also received letters from other passengers, amongst these one from Miss C.C. van Geuns, but that all of these contained only facts that had already been told by others. Miss Cornelia obviously thought that her story was interesting. She published her own story[44] in the week of 5 June 1871. One particular fact that the commission could have taken from this account, was that when Miss van Geuns arrived on board in the evening of 15 May, she found her cabin taken by an English engineer, "whose presence was still required on board for some days". She did not get her cabin on the night of the 15th or the 16th and perhaps got it only on the 18th.[45] It shows that during the last few days in Nieuwediep people were still working on the ship itself, not only on loading it.

The wreck is auctioned

To the public it was not clear that Willem III could be repaired. It created a dispute between the SMN and the insurers about whether this should be done. In the end arbitration decided on 30 November 1871 that it was in the interest of all parties that the ship would be sold.[46] In December 1871 the wreck was declared unfit for further service, and planned to be sold at auction on 10 January 1872.[47] The public was surprised that this auction brought in 20,500 GBP,[48] or 246,000 guilders. With a contracted new price of 900,000 guilders this confirmed that the ship could be repaired. The ship was insured for 800,000 guilders, of which 50% was soon paid. There was also an insurance for a good trip for 50,000 guilders, which was also paid promptly. In the end the wreckage ledger for Willem III was stated to be 85,000 guilders.[46]

Further service

Willem III is repaired

As stated above Willem III was auctioned on 10 January 1872. Her buyer was William Mc Arthur & Co from Road Lane, who renamed her Quang Se. On 3 February 1872 the wreck was then towed from Portsmouth to London by the tugboats Fiery Cross and Mac Gregor. She was brought in drydock at Millwall Dock, and while there, she was surveyed on 6 February 1872.

Smith, Pender & Co Engineers and shipbuilders in Millwall then set about a rebuilt according to the original specifications. Repairs consisted of all new hull plating above the water line, and also some below the waterline. About 230 frames had to be bent back in shape etc.Description at Lloyd's Register Foundation On 11 January 1873 she made her trials as Quang Se. She made 10.5 knots, probably because the screw was not completely in the water.[8]

First new owners

In 1873 Quang Se was sold to William Houston. On 25 May 1874 she was grounded at South Foreland (near Kent). After inspection a few plates had to be refitted. W. Houston was noted as owner, but J.A. Steel was later added with another pen. On 21 January 1875 Quang Se arrived in Port Said from the East Indies. In June 1875 James Alison Steel was noted as owner and there was talk about a change of ownership. On 10 July 1875 she arrived in Port Said from Calcutta. On 17 November 1875 she again arrived in Port Said from Suez.

Steaming for the Glen Line

In December 1875 James Mc Gregor announced that he had become the owner of Quang Se. She was to become part of the Glen Line, and therefore he wanted to rename her Glenorchy.[49] On 24 January 1876 Quang Se arrived in Port Said. On 7 November 1876 she arrived in Suez. On 17 December 1876 Quang Se approached New York harbor and hit Oyster Island, after which she had to visit a dry dock for inspection, which was finished on 12 January 1877. The report noted her owner as A.C. Gow & Co.

On 1 May 1877 some major repairs were finished. She was named Glenorchy at that moment. Somewhat later a report about repairs to the boilers etc. followed. Both these repairs also noted A.C. Gow & Co as owner. In the years since, Glenorchy is regularly noted on the Suez Canal and steaming to and from Shanghai. On 18 February 1885 she arrived in Hong Kong with 400 tons of cartridges and 100 chests of Remington rifles destined for Shanghai. The harbormaster of Hong Kong ordered this cargo to be unloaded in that port.[50] In 1886 Glenorchy was on her way from China to England when SS Prins Hendrik II of the SMN was wrecked near Aden. Most of the cargo that was saved was loaded on Glenorchy. In that year Mc Gregor Gow & Co. were noted as owners. Apart from these highlights Glenorchy was mostly steaming between London and China.

In 1890 Glenorchy passed Suez on her from Yokohama to New York. Yokohama would become a regular destination for the ship in the 1890s. In March 1891 Glenorchy was on her way from London to Penang when she collided with Maine from Baltimore near Blackwall point, which is the northern tip of Greenwich Peninsula on the Thames in London. The anchor stock and part of the bulwark of Glenorchy was broken.[51] On 7 March 1893 she arrived in Semarang, Dutch East Indies from Hong Kong under commander J. Ferguson.

On 1 December 1879 Glenorchy arrived in Suez from Melbourne. On 9 December 1897 she left Gibraltar for Rotterdam. On 20 December 1897 the SS Glenorchy arrived in London from Sidney via Dunkirk.[52] On 27 December 1897 Glenorchy was in Terneuzen. On 27 December 1897 Glenorchy captain Frakes arrived in Rotterdam. She carried silver ore and 1,253 tons of lead ore.

The Liverpool four mast barque Glenorchy

The steamship Glenorchy is sometimes mixed up with a saling ship of the same name. It is probably caused by both ships being in Rotterdam when the steamship Glenorchy was sold. The four mast sailing ship Glenorchy of 2,500 ton was built by Sunderland Shipbuilding Company.[53] Later her sailing plan was changed to that of a barque.

We see Glenorchy in arriving in Falmouth from Port Broughton, South Australia in October 1890 under Captain Taylor. In July 1894 she passed Saint Helena under Captain Baron on a trip from Rangoon to Falmouth. On 22 May 1897 Glenorchy was ready to sail in Port Pirie, Australia. In July 1897 a lifebuoy marked Glenorchy Liverpool, and some wreckage washed ashore on Vancouver Island, Canada.[54] This was said to prove her loss, but this report about the Liverpool four-mast Barque Glenorchy was later proved false.

On 20 September 1897 Glenorchy left Port Pirie again for Rotterdam still under Captain Baron. On 31 December 1897 Glenorchy captain Baron passed Lizard Point, Cornwall. On 4 January 1898 the sailing ship Glenorchy captain Baron arrived in Maassluis, a harbor before Rotterdam. She carried 3,226,685 kg of sulfur ore and or saltpeter. A warning was then published in the newspaper that no credit should be given to the crew of the English four mast ship Glenorchy.[55] On 8 January she was ready to sail in Rotterdam with destination Swansea. On 11 January 1898 the sailing ship Glenorchy left Rotterdam, and on 18 January she arrived in Swansea under Captain Baron. The Barque Glenorchy was sold to the Genovese firm Fratelli Beverino in 1898. It renamed her Fratelli Beverino. She was sunk in 1915.[56]

Italian service

By 13 January 1898 the steamship Glenorchy had been sold for 5,200 GBP to a Genovese firm. At the time she was still in Rotterdam.[57] The sale was reported two days after the sailing ship Glenorchy had left Rotterdam. All reports that the steamship Glenorchy had four masts might have been caused by this confusion.

On 22 January 1898 Glenorchy left Rotterdam for Genoa. Or so it was said, because on 9 February 1898 she was reported to have arrived in Philadelphia from Rotterdam. At one time she was owned by G.H. Lavarello in Genoa. She served as Pina, and was observed as late as 1902.[58]

References

- Campo, a, J.N.F.M. (2002), Engines of Empire: Steamshipping and State Formation in Colonial Indonesia, Verloren, Hilversum, ISBN 9065507388

- Geuns, van, Cornelia (1871), Het kortstondig bestaan van het Stoomschip Willem III, verbrand op den 19 Mei 1871, J. Heuvelink, Arnhem

- Tideman, B.J. (1870), Stoomvaart op Lange Lijnen, Joh. Numan en Zoon, Zaltbommel

- Tideman, B.J. (1880), Memoriaal van de Marine, Van Heteren Amsterdam

- Verslag van de Commissie (1871), Verslag van de Commissie belast met het Onderzoek naar de oorzaak van de ramp het Stoomschip Willem III overkomen, Stoomboekdrukkerij de Industrie, Utrecht

- Ente Morale (1902), Registro italiano per la classificazione dei bastimenti Libro registro, Pietro Pellas, Genova

- London Gazette (1875), The London Gazette

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "WILLEM III - ID 8087" (in Dutch). Stichting Maritiem-Historische Databank. 4 April 2020.

- ^ a b c Tideman 1880, p. 2e afdeling, 39.

- ^ Campo, a 2002, p. 204.

- ^ "Een der schakels met indië". De Hollandsche revue. 23 November 1910. p. 783.

- ^ Tideman 1880, p. 2e afdeling, 38.

- ^ a b c "Binnenland". De Tijd. 16 May 1871.

- ^ a b "Een flinke onderneming". Het nieuws van den dag. 16 May 1871.

- ^ a b "De verbrande stoomboot Willem III". Makassaarsch handels-blad. 11 April 1873.

- ^ a b c Verslag van de Commissie 1871, p. 3.

- ^ "Binnenland". De grondwet. 9 March 1871.

- ^ "Latere Berigten". Nieuwe Veendammer courant. 6 May 1871.

- ^ "Binnenland". Provinciale Noordbrabantsche. 9 May 1871.

- ^ "Zeetijdingen". De Maasbode. 11 May 1871.

- ^ "Binnenland". Arnhemsche courant. 17 May 1871.

- ^ "Binnenland". Provinciale Overijsselschee. 12 May 1871.

- ^ "Leger en Marine". Het Vaderland. 11 May 1871.

- ^ "Binnenland". Provinciale Overijsselschee. 17 May 1871.

- ^ "Bijvoegsel". Provinciale Noordbrabantsche. 16 May 1871.

- ^ "Bijvoegsel". Provinciale Noordbrabantsche. 20 May 1871.

- ^ "Nederlandsch-Indië". Java-bode. 22 May 1871.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Verbranden der prachtige Stoomboot Willem III". Provinciale Noordbrabantsche. 25 May 1871.

- ^ Geuns, van 1871, p. 12.

- ^ Geuns, van 1871, p. 13.

- ^ a b "Binnenland". Algemeen Handelsblad. 26 May 1871.

- ^ Verslag van de Commissie 1871, p. 47.

- ^ Geuns, van 1871, p. 15.

- ^ "Binnenland". Arnhemsche courant. 25 May 1871.

- ^ a b c "Binnenland". Algemeen Handelsblad. 25 May 1871.

- ^ "Amsterdam, Zondag 9 Juli". Algemeen Handelsblad. 10 July 1871.

- ^ "Binnenlandch Nieuws". Het Nieuws van den Dag. 25 May 1871.

- ^ "Laatste Berigten". Provinciale Drentsche. 24 May 1871.

- ^ "Binnenland". Arnhemsche courant. 24 May 1871.

- ^ "Binnenland". Arnhemsche courant. 23 May 1871.

- ^ "Binnenland". Algemeen Handelsblad. 28 May 1871.

- ^ "Voor het detachment militairen". Algemeen Handelsblad. 30 June 1871.

- ^ "Zeetijdingen". Nieuwe Veendammer courant. 10 June 1871.

- ^ "Buitenland". Algemeen Handelsblad. 17 June 1871.

- ^ "Zeetijdingen". Het Vaderland. 24 July 1871.

- ^ "Zeetijdingen". Het Vaderland. 4 August 1871.

- ^ "Binnenland". Algemeen Handelsblad. 1 June 1871.

- ^ Verslag van de Commissie 1871, p. 4.

- ^ Verslag van de Commissie 1871.

- ^ "Binnenlandsch Nieuws". Het nieuws van den dag. 23 December 1871.

- ^ Geuns, van 1871.

- ^ Geuns, van 1871, p. 9.

- ^ a b "Binnenland". Algemeen Handelsblad. 1 June 1872.

- ^ "Binnenland". Het Vaderland. 19 December 1871.

- ^ "Scheepstijdingen". Algemeen Handelsblad. 13 January 1872.

- ^ London Gazette 1875, p. 6642.

- ^ "Nederlandsch-Indië". De locomotief. 14 September 1882.

- ^ "Glenorchy". Algemeen Handelsblad. 20 March 1891.

- ^ "Engelsche Havens". Scheepvaart. 21 December 1897.

- ^ "Buitenland". Dagblad van Zuidholland. 14 September 1882.

- ^ "Victoria, B.C. 9 Juli". Rotterdamsch nieuwsblad. 12 July 1897.

- ^ "Waarschuwing". Scheepvaart. 5 January 1898.

- ^ "FRATELLI BEVERINO". ARCHIVIO VECCHIE VELE (in Italian). Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ^ "Scheepberichten". Scheepvaart. 13 January 1898.

- ^ Ente Morale 1902, p. 507.

External links

- Willem III at Scottish Built ships

- Biography of captain Pieter van der Velden Erdbrink, who assisted in the evacuation of the ship

- Inspection reports etc. for Glenorchy at Lloyd's Register Foundation

- The Glen Line for which the ship later sailed

- Grand Collection of sailing ship photographs at State Library of South Australia