Rwanda

Republic of Rwanda Repubulika y'u Rwanda (Kinyarwanda) République du Rwanda (French) Jamhuri ya Rwanda (Swahili) | |

|---|---|

| Motto: "Ubumwe, Umurimo, Gukunda Igihugu" (English: "Unity, Work, Patriotism") (French: "Unité, Travail, Patriotisme") (Swahili: "Umoja, Kazi, Uzalendo") | |

| Anthem: "Rwanda Nziza" (English: "Beautiful Rwanda") | |

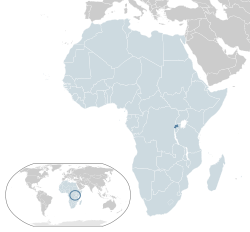

Location of Rwanda (dark blue) in Africa (light blue) | |

| Capital and largest city | Kigali 1°56′38″S 30°3′34″E / 1.94389°S 30.05944°E |

| Official languages | |

| Ethnic groups (1994) |

|

| Religion |

|

| Demonym(s) |

|

| Government | Unitary presidential republic under an authoritarian dictatorship[3][4][5][6][7][8] |

| Paul Kagame | |

| Édouard Ngirente | |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| Senate | |

| Chamber of Deputies | |

| Formation | |

| 15th century | |

• Part of German East Africa | 1897–1916 |

• Part of Ruanda-Urundi | 1916–1962 |

| 1959–1961 | |

| 1 July 1961 | |

• Independence from Belgium | 1 July 1962 |

• Admitted to the UN | 18 September 1962 |

| 26 May 2003 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 26,338[9] km2 (10,169 sq mi) (144th) |

• Water (%) | 6.341 |

| Population | |

• 2024 estimate | 13,623,302[9] (76th) |

• Density | 517/km2 (1,339.0/sq mi) (22nd) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2016) | 43.7[11] medium inequality |

| HDI (2022) | low (161st) |

| Currency | Rwandan franc (RWF) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (CAT) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy |

| Drives on | Right |

| Calling code | +250 |

| ISO 3166 code | RW |

| Internet TLD | .rw |

Rwanda,[a] officially the Republic of Rwanda, is a landlocked country in the Great Rift Valley of East Africa, where the African Great Lakes region and Southeast Africa converge. Located a few degrees south of the Equator, Rwanda is bordered by Uganda, Tanzania, Burundi, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. It is highly elevated, giving it the sobriquet "land of a thousand hills" (French: pays des mille collines), with its geography dominated by mountains in the west and savanna to the southeast, with numerous lakes throughout the country. The climate is temperate to subtropical, with two rainy seasons and two dry seasons each year. It is the most densely populated mainland African country; among countries larger than 10,000 km2, it is the fifth-most densely populated country in the world. Its capital and largest city is Kigali.

Hunter-gatherers settled the territory in the Stone and Iron Ages, followed later by Bantu peoples. The population coalesced first into clans, and then into kingdoms. In the 15th century, one kingdom, under King Gihanga, managed to incorporate several of its close neighbor territories establishing the Kingdom of Rwanda. The Kingdom of Rwanda dominated from the mid-eighteenth century, with the Tutsi kings conquering others militarily, centralising power, and enacting unifying policies. In 1897, Germany colonized Rwanda as part of German East Africa, followed by Belgium, which took control in 1916 during World War I. Both European nations ruled through the Rwandan king and perpetuated a pro-Tutsi policy. The Hutu population revolted in 1959. They massacred numerous Tutsi and ultimately established an independent, Hutu-dominated republic in 1962 led by President Grégoire Kayibanda. A 1973 military coup overthrew Kayibanda and brought Juvénal Habyarimana to power, who retained the pro-Hutu policy. The Tutsi-led Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) launched a civil war in 1990. Habyarimana was assassinated in April 1994. Social tensions erupted in the Rwandan genocide that spanned one hundred days. The RPF ended the genocide with a military victory in July 1994.

Rwanda has been governed by the RPF as a de facto one-party state since 1994 with former commander Paul Kagame as President since 2000. The country has been governed by a series of centralized authoritarian governments since precolonial times. Although Rwanda has low levels of corruption compared with neighbouring countries, it ranks among the lowest in international measurements of government transparency, civil liberties and quality of life. The population is young and predominantly rural; Rwanda has one of the youngest populations in the world. Rwandans are drawn from just one cultural and linguistic group, the Banyarwanda. However, within this group there are three subgroups: the Hutu, Tutsi and Twa. The Twa are a forest-dwelling pygmy people and are often considered descendants of Rwanda's earliest inhabitants. Christianity is the largest religion in the country; the principal and national language is Kinyarwanda, spoken by native Rwandans, with English, French and Swahili serving as additional official foreign languages.

Rwanda's economy is based mostly on subsistence agriculture. Coffee and tea are the major cash crops that it exports. Tourism is a fast-growing sector and is now the country's leading foreign exchange earner. As of the most recent survey in 2019/20, 48.8% of the population is affected by multidimensional poverty and an additional 22.7% vulnerable to it. The country is a member of the African Union, the United Nations, the Commonwealth of Nations (one of few member states that does not have any historical links with the British Empire), COMESA, OIF and the East African Community.

History

Modern human settlement of what is now Rwanda dates from, at the latest, the last glacial period, either in the Neolithic period around 8000 BC, or in the long humid period which followed, up to around 3000 BC.[15] Archaeological excavations have revealed evidence of sparse settlement by hunter-gatherers in the late Stone Age, followed by a larger population of early Iron Age settlers, who produced dimpled pottery and iron tools.[16][17] These early inhabitants were the ancestors of the Twa, aboriginal pygmy hunter-gatherers who remain in Rwanda today. Then by 3,000BC, Central Sudanic and Kuliak farmers and herders began settling into Rwanda, followed by South Cushitic speaking herders in 2,000BC.[18][19][20] The forest-dwelling Twa lost much of their habitat and moved to the mountain slopes.[21] Between 800 BC and 1500 AD, a number of Bantu groups migrated into Rwanda, clearing forest land for agriculture.[20][22] Historians have several theories regarding the nature of the Bantu migrations; one theory is that the first settlers were Hutu, while the Tutsi migrated later to form a distinct racial group, possibly of Nilo-hamitic origin.[23] An alternative theory is that the migration was slow and steady, with incoming groups integrating into rather than conquering the existing society.[20][24] Under this theory, the Hutu and Tutsi distinction arose later and was a class distinction rather than a racial one.[25][26]

The earliest form of social organisation in the area was the clan (ubwoko).[27] The clans were not limited to genealogical lineages or geographical area, and most included Hutu, Tutsi, and Twa.[28] From the 15th century, the clans began to merge into kingdoms.[29] One kingdom, under King Gihanga, managed to incorporate several of its close neighbor territories establishing the Kingdom of Rwanda. By 1700, around eight kingdoms had existed in the present-day Rwanda.[30] One of these, the Kingdom of Rwanda ruled by the Tutsi Nyiginya clan, became increasingly dominant from the mid-eighteenth century.[31] The kingdom reached its greatest extent during the nineteenth century under the reign of King Kigeli Rwabugiri. Rwabugiri conquered several smaller states, expanded the kingdom west and north,[31][32] and initiated administrative reforms; these included ubuhake, in which Tutsi patrons ceded cattle, and therefore privileged status, to Hutu or Tutsi clients in exchange for economic and personal service,[33] and uburetwa, a corvée system in which Hutu were forced to work for Tutsi chiefs.[32] Rwabugiri's changes caused a rift to grow between the Hutu and Tutsi populations.[32] The Twa were better off than in pre-Kingdom days, with some becoming dancers in the royal court,[21] but their numbers continued to decline.[34]

The Berlin Conference of 1884 assigned the territory to the German Empire, who declared it to be part of German East Africa. In 1894, explorer Gustav Adolf von Götzen was the first European to cross the entire territory of Rwanda; he crossed from the south-east to Lake Kivu and met the king.[35][36] In 1897, Germany established a presence in Rwanda with the formation of an alliance with the king, beginning the colonial era.[37] The Germans did not significantly alter the social structure of the country, but exerted influence by supporting the king and the existing hierarchy, and delegating power to local chiefs.[38][39] Belgian forces invaded Rwanda and Burundi in 1916, during World War I, and later, in 1922, they started to rule both Rwanda and Burundi as a League of Nations mandate called Ruanda-Urundi and started a period of more direct colonial rule.[40] The Belgians simplified and centralised the power structure,[41] introduced large-scale projects in education, health, public works, and agricultural supervision, including new crops and improved agricultural techniques to try to reduce the incidence of famine.[42] Both the Germans and the Belgians, in the wake of New Imperialism, promoted Tutsi supremacy, considering the Hutu and Tutsi different races.[43] In 1935, Belgium introduced an identity card system, which labelled each individual as either Tutsi, Hutu, Twa or Naturalised. While it had been previously possible for particularly wealthy Hutu to become honorary Tutsi, the identity cards prevented any further movement between the classes.[44]

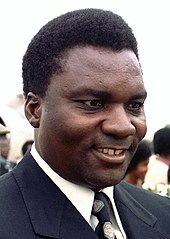

Belgium continued to rule Ruanda-Urundi (of which Rwanda formed the northern part) as a UN trust territory after the Second World War, with a mandate to oversee eventual independence.[45][46] Tensions escalated between the Tutsi, who favoured early independence, and the Hutu emancipation movement, culminating in the 1959 Rwandan Revolution: Hutu activists began killing Tutsi and destroying their houses,[47] forcing more than 100,000 people to seek refuge in neighbouring countries.[48][49] In 1961, the suddenly pro-Hutu Belgians held a referendum in which the country voted to abolish the monarchy. Rwanda was separated from Burundi and gained independence on 1 July 1962,[50] which is commemorated as Independence Day, a national holiday.[51] Cycles of violence followed, with exiled Tutsi attacking from neighbouring countries and the Hutu retaliating with large-scale slaughter and repression of the Tutsi.[52] In 1973, Juvénal Habyarimana took power in a military coup. Pro-Hutu discrimination continued, but there was greater economic prosperity and a reduced amount of violence against Tutsi.[53] The Twa remained marginalised, and by 1990 were almost entirely forced out of the forests by the government; many became beggars.[54] Rwanda's population had increased from 1.6 million people in 1934 to 7.1 million in 1989, leading to competition for land.[55]

In 1990, the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), a rebel group composed of Tutsi refugees, invaded northern Rwanda from their base in Uganda, initiating the Rwandan Civil War.[56] The group condemned the Hutu-dominated government for failing to democratize and confront the problems facing these refugees. Neither side was able to gain a decisive advantage in the war,[57] but by 1992 it had weakened Habyarimana's authority; mass demonstrations forced him into a coalition with the domestic opposition and eventually to sign the 1993 Arusha Accords with the RPF.[58]

Rwandan genocide

The cease-fire ended on 6 April 1994 when Habyarimana's plane was shot down near Kigali Airport, killing him.[59] The shooting down of the plane served as the catalyst for the Rwandan genocide, which began within a few hours. Over the course of approximately 100 days, between 500,000 and 1,000,000[60] Tutsi and politically moderate Hutu were killed in well-planned attacks on the orders of the interim government.[61] Many Twa were also killed, despite not being directly targeted.[54]

The Tutsi RPF restarted their offensive, and took control of the country methodically, gaining control of the whole country by mid-July.[62] The international response to the genocide was limited, with major powers reluctant to strengthen the already overstretched UN peacekeeping force.[63] When the RPF took over, approximately two million Hutu fled to neighbouring countries, in particular Zaïre, fearing reprisals;[64] additionally, the RPF-led army was a key belligerent in the First and Second Congo Wars.[65] Within Rwanda, a period of reconciliation and justice began, with the establishment of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) and the reintroduction of Gacaca, a traditional village court system.[66] Since 2000 Rwanda's economy,[67] tourist numbers,[68] and Human Development Index have grown rapidly;[69] between 2006 and 2011 the poverty rate reduced from 57% to 45%,[70] while life expectancy rose from 46.6 years in 2000[71] to 65.4 years in 2021.[72]

In 2009, Rwanda joined the Commonwealth of Nations, although the country was never part of the British Empire.

Politics and government

Rwanda is a de facto one-party state[3][4][5][6][7][8] ruled by the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) and its leader Paul Kagame continuously since the end of the civil war in 1994.[73][74] Although Rwanda is nominally democratic, elections are manipulated in various ways, which include banning opposition parties, arresting or assassinating critics, and electoral fraud.[75] The RPF is a Tutsi-dominated party but receives support from other communities as well.[76]

The constitution was adopted following a national referendum in 2003, replacing the transitional constitution which had been in place since 1994.[77] The constitution mandates a multi-party system of government, with politics based on democracy and elections.[78] However, the constitution places conditions on how political parties may operate. Article 54 states that "political organizations are prohibited from basing themselves on race, ethnic group, tribe, clan, region, sex, religion or any other division which may give rise to discrimination".[79] The president of Rwanda is the head of state,[80] and has broad powers including creating policy in conjunction with the Cabinet of Rwanda,[81] commanding the armed forces,[82] negotiating and ratifying treaties,[83] signing presidential orders,[84] and declaring war or a state of emergency.[82] The president is elected every seven years,[85] and appoints the prime minister and all other members of the Cabinet.[86] The Parliament consists of two chambers. It makes legislation and is empowered by the constitution to oversee the activities of the president and the Cabinet.[87] The lower chamber is the Chamber of Deputies, which has 80 members serving five-year terms. Twenty-four of these seats are reserved for women, elected through a joint assembly of local government officials; another three seats are reserved for youth and disabled members; the remaining 53 are elected by universal suffrage under a proportional representation system.[88]

Rwanda's legal system is largely based on German and Belgian civil law systems and customary law.[72] The judiciary is independent of the executive branch,[89] although the president and the Senate are involved in the appointment of Supreme Court judges.[90] Human Rights Watch has praised the Rwandan government for progress made in the delivery of justice including the abolition of the death penalty,[91] but also alleges interference in the judicial system by members of the government, such as the politically motivated appointment of judges, misuse of prosecutorial power, and pressure on judges to make particular decisions.[92] The constitution provides for two types of courts: ordinary and specialised.[93] Ordinary courts are the Supreme Court, the High Court, and regional courts, while specialised courts are military courts[93] and a system of commercial courts created in 2011 to expedite commercial litigations.[94] Between 2004 and 2012, a system of Gacaca courts was in operation.[95] Gacaca, a Rwandan traditional court operated by villages and communities, was revived to expedite the trials of genocide suspects.[96] The court succeeded in clearing the backlog of genocide cases, but was criticised by human rights groups as not meeting legal fair standard.[97]

Rwanda has low corruption levels relative to most other African countries; in 2014, Transparency International ranked Rwanda as the fifth-cleanest out of 47 countries in Sub-Saharan Africa and 55th-cleanest out of 175 in the world.[98][99] The constitution provides for an ombudsman, whose duties include prevention and fighting of corruption.[100][101] Public officials (including the president) are required by the constitution to declare their wealth to the ombudsman and to the public; those who do not comply are suspended from office.[102] Despite this, Human Rights Watch notes extensive political repression throughout the country, including illegal and arbitrary detention, threats or other forms of intimidation, disappearances, politically motivated trials, and the massacre of peacefully protesting civilians.[103]

Rwanda is a member of the United Nations,[104] African Union, Francophonie,[105] East African Community,[106] and the Commonwealth of Nations.[107] For many years during the Habyarimana regime, the country maintained close ties with France, as well as Belgium, the former colonial power.[108] Under the RPF government, however, Rwanda has sought closer ties with neighbouring countries in the East African Community and with the English-speaking world. Diplomatic relations with France were suspended in 2006 following the indictment of Rwandan officials by a French judge,[109] and despite their restoration in 2010, as of 2015 relations between the countries remain strained.[110] Relations with the Democratic Republic of the Congo were tense following Rwanda's involvement in the First and Second Congo Wars;[65] the Congolese army alleged Rwandan attacks on their troops, while Rwanda blamed the Congolese government for failing to suppress Hutu rebels in North and South Kivu provinces.[111][112] In 2010, the United Nations released a report accusing the Rwandan army of committing wide scale human rights violations and crimes against humanity in the Democratic Republic of the Congo during the First and Second Congo Wars, charges denied by the Rwandan government.[113] Relations soured further in 2012, as Kinshasa accused Rwanda of supporting the M23 rebellion, an insurgency in the eastern Congo.[114] As of 2015, peace has been restored and relations are improving.[115]

Rwanda's relationship with Uganda was also tense for much of the 2000s following a 1999 clash between the two countries' armies as they backed opposing rebel groups in the Second Congo War,[116] but improved significantly in the early 2010s.[117][118] In 2019, relations between the two countries deteriorated, with Rwanda closing its borders with Uganda.[119][120]

Administrative divisions

Before western colonization, the Rwandan government system had a quasi-system of political pluralism and power sharing.[121] Despite there being a strict hierarchy, the pre-colonial system achieved an established, combined system of "centralized power and decentralized autonomous units." Under the monarch, the elected Chief governed a province that was divided into multiple districts. Two other officials appointed by head Chief governed the districts; one official was allocated power over the land while the other oversaw cattle. The king (mwami) exercised control through a system of provinces, districts, hills, and neighbourhoods.[122] As of 2003, the constitution divided Rwanda into provinces (intara), districts (uturere), cities, municipalities, towns, sectors (imirenge), cells (utugari), and villages (imidugudu); the larger divisions, and their borders, are established by Parliament.[123] In January 2006, Rwanda was reorganized such that twelve provinces were merged to create five, and 106 districts were merged into thirty.[124] The present borders drawn in 2006 aimed at decentralising power and removing associations with the old system and the genocide. The previous structure of twelve provinces associated with the largest cities was replaced with five provinces based primarily on geography.[125] These are Northern Province, Southern Province, Eastern Province, Western Province, and the Municipality of Kigali in the centre.

The five provinces act as intermediaries between the national government and their constituent districts to ensure that national policies are implemented at the district level. The Rwanda Decentralisation Strategic Framework developed by the Ministry of Local Government assigns to provinces the responsibility for "coordinating governance issues in the Province, as well as monitoring and evaluation".[126] Each province is headed by a governor, appointed by the president and approved by the Senate.[127] The districts are responsible for coordinating public service delivery and economic development. They are divided into sectors, which are responsible for the delivery of public services as mandated by the districts.[128] Districts and sectors have directly elected councils, and are run by an executive committee selected by that council.[129] The cells and villages are the smallest political units, providing a link between the people and the sectors.[128] All adult resident citizens are members of their local cell council, from which an executive committee is elected.[129] The city of Kigali is a provincial-level authority, which coordinates urban planning within the city.[126]

Geography

At 26,338 square kilometres (10,169 sq mi), Rwanda is the world's 149th-largest country,[130] and the fourth smallest on the African mainland after Gambia, Eswatini, and Djibouti.[130] It is comparable in size to Burundi, Haiti and Albania.[72][131] The entire country is at a high altitude: the lowest point is the Rusizi River at 950 metres (3,117 ft) above sea level.[72] Rwanda is located in Central/Eastern Africa, and is bordered by the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the west, Uganda to the north, Tanzania to the east, and Burundi to the south.[72] It lies a few degrees south of the equator and is landlocked.[132] The capital, Kigali, is located near the centre of Rwanda.[133]

The watershed between the major Congo and Nile drainage basins runs from north to south through Rwanda, with around 80% of the country's area draining into the Nile and 20% into the Congo via the Rusizi River and Lake Tanganyika.[134] The country's longest river is the Nyabarongo, which rises in the south-west, flows north, east, and southeast before merging with the Ruvubu to form the Kagera; the Kagera then flows due north along the eastern border with Tanzania. The Nyabarongo-Kagera eventually drains into Lake Victoria, and its source in Nyungwe Forest is a contender for the as-yet undetermined overall source of the Nile.[135] Rwanda has many lakes, the largest being Lake Kivu. This lake occupies the floor of the Albertine Rift along most of the length of Rwanda's western border, and with a maximum depth of 480 metres (1,575 ft),[136] it is one of the twenty deepest lakes in the world.[137] Other sizeable lakes include Burera, Ruhondo, Muhazi, Rweru, and Ihema, the last being the largest of a string of lakes in the eastern plains of Akagera National Park.[138]

Mountains dominate central and western Rwanda and the country is sometimes called "Pays des mille collines" in French ("Land of a thousand hills").[139] They are part of the Albertine Rift Mountains that flank the Albertine branch of the East African Rift, which runs from north to south along Rwanda's western border.[140] The highest peaks are found in the Virunga volcano chain in the northwest; this includes Mount Karisimbi, Rwanda's highest point, at 4,507 metres (14,787 ft).[141] This western section of the country lies within the Albertine Rift montane forests ecoregion.[140] It has an elevation of 1,500 to 2,500 metres (4,921 to 8,202 ft).[142] The centre of the country is predominantly rolling hills, while the eastern border region consists of savanna, plains and swamps.[143]

Climate

Rwanda has a temperate tropical highland climate, with lower temperatures than are typical for equatorial countries because of its high elevation.[132] Kigali, in the centre of the country, has a typical daily temperature range between 15 and 28 °C (59 and 82 °F), with little variation through the year.[144] There are some temperature variations across the country; the mountainous west and north are generally cooler than the lower-lying east.[145] There are two rainy seasons in the year; the first runs from February to June and the second from September to December. These are separated by two dry seasons: the major one from June to September, during which there is often no rain at all, and a shorter and less severe one from December to February.[146] Rainfall varies geographically, with the west and northwest of the country receiving more precipitation annually than the east and southeast.[147] Global warming has caused a change in the pattern of the rainy seasons. According to a report by the Strategic Foresight Group, change in climate has reduced the number of rainy days experienced during a year, but has also caused an increase in frequency of torrential rains.[148] Both changes have caused difficulty for farmers, decreasing their productivity.[149] Strategic Foresight also characterise Rwanda as a fast warming country, with an increase in average temperature of between 0.7 °C to 0.9 °C over fifty years.[148]

Biodiversity

In prehistoric times, montane forest occupied one-third of the territory of present-day Rwanda. Naturally occurring vegetation is now mostly restricted to the three national parks, with terraced agriculture dominating the rest of the country.[150] Nyungwe, the largest remaining tract of forest, contains 200 species of tree as well as orchids and begonias.[151] Vegetation in the Volcanoes National Park is mostly bamboo and moorland, with small areas of forest.[150] By contrast, Akagera has a savanna ecosystem in which acacia dominates the flora. There are several rare or endangered plant species in Akagera, including Markhamia lutea and Eulophia guineensis.[152][153]

The greatest diversity of large mammals is found in the three national parks, which are designated conservation areas.[154] Akagera contains typical savanna animals such as giraffes and elephants,[155] while Volcanoes is home to an estimated one-third of the worldwide mountain gorilla population.[156] Nyungwe Forest boasts thirteen primate species including common chimpanzees and Ruwenzori colobus arboreal monkeys; the Ruwenzori colobus move in groups of up to 400 individuals, the largest troop size of any primate in Africa.[157]

Rwanda's population of lions was destroyed in the aftermath of the genocide of 1994, as national parks were turned into camps for displaced people and the remaining animals were poisoned by cattle herders. In June 2015, two South African parks donated seven lions to Akagera National Park, reestablishing a lion population in Rwanda.[158] The lions were held initially in a fenced-off area of the park, and then collared and released into the wild a month later.[159]

Eighteen endangered black rhinos were brought to Rwanda in 2017 from South Africa.[160] After positive results, five more black rhinos were delivered to Akagera National Park from zoos all over Europe in 2019.[161]

Similarly, the white rhino population is growing in Rwanda. In 2021, Rwanda received 30 white rhinos from South Africa with the goal of Akagera being a safe breeding ground for the near-threatened species.[162][163]

There are 670 bird species in Rwanda, with variation between the east and the west.[164] Nyungwe Forest, in the west, has 280 recorded species, of which 26 are endemic to the Albertine Rift;[164] endemic species include the Rwenzori turaco and handsome spurfowl.[165] Eastern Rwanda, by contrast, features savanna birds such as the black-headed gonolek and those associated with swamps and lakes, including storks and cranes.[164]

Recent entomological work in the country has revealed a rich diversity of praying mantises,[166] including a new species Dystacta tigrifrutex, dubbed the "bush tiger mantis".[167]

Rwanda contains three terrestrial ecoregions: Albertine Rift montane forests, Victoria Basin forest-savanna mosaic, and Ruwenzori-Virunga montane moorlands.[168] The country had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 3.85/10, ranking it 139th globally out of 172 countries.[169]

Economy

Rwanda's economy suffered heavily during the 1994 genocide, with widespread loss of life, failure to maintain infrastructure, looting, and neglect of important cash crops. This caused a large drop in GDP and destroyed the country's ability to attract private and external investment.[72] The economy has since strengthened, with per-capita nominal GDP estimated at $909.9 in 2022,[170] compared with $127 in 1994.[171] As of the most recent survey in 2019/20, 48.8% of the population continues to be affected by multidimensional poverty and an additional 22.7% vulnerable to it.[172] Major export markets include China, Germany, and the United States.[72] The economy is managed by the central National Bank of Rwanda and the currency is the Rwandan franc; in December 2023, the exchange rate was 1250 francs to one United States dollar.[173] Rwanda joined the East African Community in 2007, and has ratified a plan for monetary union amongst the seven member nations,[174] which could eventually lead to a common East African shilling.[175]

Rwanda is a country of few natural resources,[132] and the economy is based mostly on subsistence agriculture by local farmers using simple tools.[176] An estimated 90% of the working population farms, and agriculture constituted an estimated 32.5% of GDP in 2014.[72] Farming techniques are basic, with small plots of land and steep slopes.[177] Since the mid-1980s, farm sizes and food production have been decreasing, due in part to the resettlement of displaced people.[178][132] Despite Rwanda's fertile ecosystem, food production often does not keep pace with population growth, and food imports are required.[72] However, in recent years with the growth of agriculture, the situation has improved.[179]

Subsistence crops grown in the country include matoke (green bananas), which occupy more than a third of the country's farmland,[177] potatoes, beans, sweet potatoes, cassava, wheat and maize.[177] Coffee and tea are the major cash crops for export, with the high altitudes, steep slopes and volcanic soils providing favourable conditions.[177] Reports have established that more than 400,000 Rwandans make their living from coffee plantation.[181] Reliance on agricultural exports makes Rwanda vulnerable to shifts in their prices.[182] Animals raised in Rwanda include cows, goats, sheep, pigs, chicken, and rabbits, with geographical variation in the numbers of each.[183] Production systems are mostly traditional, although there are a few intensive dairy farms around Kigali.[183] Shortages of land and water, insufficient and poor-quality feed, and regular disease epidemics with insufficient veterinary services are major constraints that restrict output. Fishing takes place on the country's lakes, but stocks are very depleted, and live fish are being imported in an attempt to revive the industry.[184]

The industrial sector is small, contributing 14.8% of GDP in 2014.[72] Products manufactured include cement, agricultural products, small-scale beverages, soap, furniture, shoes, plastic goods, textiles and cigarettes.[72] Rwanda's mining industry is an important contributor, generating US$93 million in 2008.[185] Minerals mined include cassiterite, wolframite, gold, and coltan, which is used in the manufacture of electronic and communication devices such as mobile phones.[185][186]

Rwanda's service sector suffered during the late-2000s recession as bank lending, foreign aid projects and investment were reduced.[187] The sector rebounded in 2010, becoming the country's largest sector by economic output and contributing 43.6% of the country's GDP.[72] Key tertiary contributors include banking and finance, wholesale and retail trade, hotels and restaurants, transport, storage, communication, insurance, real estate, business services and public administration including education and health.[187]

Tourism is one of the fastest-growing economic resources and became the country's leading foreign exchange earner in 2007.[188] In spite of the genocide's legacy, the country is increasingly perceived internationally as a safe destination.[189] The number of tourist arrivals in 2013 was 864,000 people, up from 504,000 in 2010.[68] Revenue from tourism was US$303 million in 2014, up from just US$62 million in 2000.[190] The largest contributor to this revenue was mountain gorilla tracking, in the Volcanoes National Park;[190] Rwanda is one of only three countries in which mountain gorillas can be visited safely; the gorillas attract thousands of visitors per year, who are prepared to pay high prices for permits.[191] Other attractions include Nyungwe Forest, home to chimpanzees, Ruwenzori colobus and other primates, the resorts of Lake Kivu, and Akagera, a small savanna reserve in the east of the country.[192]

Rwanda was ranked 104th in the Global Innovation Index in 2024.[193]

Media and communications

The largest radio and television stations are state-run, and the majority of newspapers are owned by the government.[194] Most Rwandans have access to radio; during the 1994 genocide, the radio station Radio Télévision Libre des Mille Collines broadcast across the country, and helped to fuel the killings through anti-Tutsi propaganda.[194] As of 2015, the state-run Radio Rwanda was the largest station and the main source of news throughout the country.[194] Television access is limited, with most homes not having their own set.[195] The government rolled out digital television in 2014, and a year later there were seven national stations operating, up from just one in the pre-2014 analogue era.[196] The press is tightly restricted, and newspapers routinely self-censor to avoid government reprisals.[194] Nonetheless, publications in Kinyarwanda, English, and French critical of the government are widely available in Kigali. Restrictions were increased in the run-up to the Rwandan presidential election of 2010, with two independent newspapers, Umuseso and Umuvugizi, being suspended for six months by the High Media Council.[197]

The country's oldest telecommunications group, Rwandatel, went into liquidation in 2011, having been 80% owned by Libyan company LAP Green.[198] The company was acquired in 2013 by Liquid Telecom,[199] a company providing telecommunications and fibre optic networks across eastern and southern Africa.[200] As of 2015, Liquid Telecom provides landline service to 30,968 subscribers, with mobile operator MTN Rwanda serving an additional 15,497 fixed line subscribers.[201] Landlines are mostly used by government institutions, banks, NGOs and embassies, with private subscription levels low.[202] As of 2015, mobile phone penetration in the country is 72.6%,[203] up from 41.6% in 2011.[204] MTN Rwanda is the leading provider, with 3,957,986 subscribers, followed by Tigo with 2,887,328, and Bharti Airtel with 1,336,679.[201] Rwandatel has also previously operated a mobile phone network, but the industry regulator revoked its licence in April 2011, following the company's failure to meet agreed investment commitments.[205] Internet penetration is low but rising rapidly; in 2015 there were 12.8 internet users per 100 people,[203] up from 2.1 in 2007.[206] In 2011, a 2,300-kilometre (1,400 mi) fibre-optic telecommunications network was completed, intended to provide broadband services and facilitate electronic commerce.[207] This network is connected to SEACOM, a submarine fibre-optic cable connecting communication carriers in southern and eastern Africa. Within Rwanda the cables run along major roads, linking towns around the country.[207] Mobile provider MTN also runs a wireless internet service accessible in most areas of Kigali via pre-paid subscription.[208]

In October 2019, Mara Corporation launched the first African-made smartphone in Rwanda.[209]

Infrastructure

The Rwandan government prioritised funding of water supply development during the 2000s, significantly increasing its share of the national budget.[210] This funding, along with donor support, caused a rapid increase in access to safe water; in 2015, 74% of the population had access to safe water,[211] up from about 55% in 2005;[210] the government has committed to increasing this to 100% by 2017.[211] The country's water infrastructure consists of urban and rural systems that deliver water to the public, mainly through standpipes in rural areas and private connections in urban areas. In areas not served by these systems, hand pumps and managed springs are used.[212] Despite rainfall exceeding 750 millimetres (30 in) annually in most of the country,[213] little use is made of rainwater harvesting, and residents are forced to use water very sparingly, relative to usage in other African countries.[211] Access to sanitation remains low; the United Nations estimates that in 2006, 34% of urban and 20% of rural dwellers had access to improved sanitation,[214] with this statistic increasing to 92% for the total population (95% urban and 91% urban) in 2022.[215] Kigali is one of the cleanest cities in Africa.[216] Government policy measures to improve sanitation are limited, focusing only on urban areas.[214] The majority of the population, both urban and rural, use public shared pit latrines.[214]

Rwanda's electricity supply was, until the early 2000s, generated almost entirely from hydroelectric sources; power stations on Lakes Burera and Ruhondo provided 90% of the country's electricity.[217] A combination of below average rainfall and human activity, including the draining of the Rugezi wetlands for cultivation and grazing, caused the two lakes' water levels to fall from 1990 onwards; by 2004 levels were reduced by 50%, leading to a sharp drop in output from the power stations.[218] This, coupled with increased demand as the economy grew, precipitated a shortfall in 2004 and widespread loadshedding.[218] As an emergency measure, the government installed diesel generators north of Kigali; by 2006 these were providing 56% of the country's electricity, but were very costly.[218] The government enacted a number of measures to alleviate this problem, including rehabilitating the Rugezi wetlands, which supply water to Burera and Ruhondo and investing in a scheme to extract methane gas from Lake Kivu, expected in its first phase to increase the country's power generation by 40%.[219] Only 18% of the population had access to electricity in 2012, though this had risen from 10.8% in 2009.[220] The government's Economic Development and Poverty Reduction Strategy for 2013–18 aims to increase access to electricity to 70% of households by 2017.[221]

The government has increased investment in the transport infrastructure of Rwanda since the 1994 genocide, with aid from the United States, European Union, Japan, and others. The transport system consists primarily of the road network, with paved roads between Kigali and most other major cities and towns in the country.[222] Rwanda is linked by road to other countries in the East African Community, namely Uganda, Tanzania, Burundi and Kenya, as well as to the eastern Congolese cities of Goma and Bukavu; the country's most important trade route is the road to the port of Mombasa via Kampala and Nairobi, which is known as the Northern Corridor.[223] The principal form of public transport in the country is the minibus, accounting for more than half of all passenger carrying capacity.[224] Some minibuses, particularly in Kigali,[225] operate an unscheduled service, under a shared taxi system,[226] while others run to a schedule, offering express routes between the major cities. There are a smaller number of large buses,[224] which operate a scheduled service around the country. The principal private hire vehicle is the motorcycle taxi; in 2013 there were 9,609 registered motorcycle taxis in Rwanda, compared with just 579 taxicabs.[224] Coach services are available to various destinations in neighbouring countries. The country has an international airport at Kigali that serves several international destinations, the busiest routes being those to Nairobi and Entebbe;[227] there is one domestic route, between Kigali and Kamembe Airport near Cyangugu.[228] In 2017, construction began on the Bugesera International Airport, to the south of Kigali, which will become the country's largest when it opens, complementing the existing Kigali airport.[229] The national carrier is RwandAir, and the country is served by seven foreign airlines.[227] As of 2015 the country had no railways, but there is a project underway, in conjunction with Burundi and Tanzania, to extend the Tanzanian Central Line into Rwanda; the three countries have invited expressions of interest from private firms to form a public private partnership for the scheme.[230] There is no public water transport between the port cities on Lake Kivu, although a limited private service exists and the government has initiated a programme to develop a full service.[231] The Ministry of Infrastructure is also investigating the feasibility of linking Rwanda to Lake Victoria via shipping on the Akagera River.[231]

Demographics

| Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Kigali  Gisenyi |

1 | Kigali | Kigali | 1,132,168 |  Butare  Gitarama | ||||

| 2 | Gisenyi | Western | 136,830 | ||||||

| 3 | Butare | Southern | 89,600 | ||||||

| 4 | Gitarama | Southern | 87,163 | ||||||

| 5 | Ruhengeri | Northern | 86,685 | ||||||

| 6 | Byumba | Northern | 70,593 | ||||||

| 7 | Cyangugu | Western | 63,883 | ||||||

| 8 | Kibuye | Western | 48,024 | ||||||

| 9 | Rwamagana | Eastern | 47,203 | ||||||

| 10 | Nzega | Southern | 46,240 | ||||||

As of 2015, the National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda estimated Rwanda's population to be 11,262,564,[233] while the projection for 2022 was 13,246,394.[234] The 2012 census recorded a population of 10,515,973.[235] The population is young: in the 2012 census, 43.3% of the population were aged 15 and under, and 53.4% were between 16 and 64.[236] According to the CIA World Factbook, the annual birth rate is estimated at 40.2 births per 1,000 inhabitants in 2015, and the death rate at 14.9.[72] The life expectancy is 67.67 years (69.27 years for females and 67.11 years for males), which is the 26th lowest out of 224 countries and territories.[72][237] The overall sex ratio of the country is 95.9 males per 100 females.[72]

At 445 inhabitants per square kilometre (1,150/sq mi),[233] Rwanda's population density is amongst the highest in Africa.[238] Historians such as Gérard Prunier believe that the 1994 genocide can be partly attributed to the population density.[55] The population is predominantly rural, with a few large towns; dwellings are evenly spread throughout the country.[239] The only sparsely populated area of the country is the savanna land in the former province of Umutara and Akagera National Park in the east.[240] Kigali is the largest city, with a population of around one million.[241] Its rapidly increasing population challenges its infrastructural development.[72][242][243] According to the 2012 census, the second largest city is Gisenyi, which lies adjacent to Lake Kivu and the Congolese city of Goma, and has a population of 126,000.[244] Other major towns include Ruhengeri, Butare, and Muhanga, all with populations below 100,000.[244] The urban population rose from 6% of the population in 1990,[242] to 16.6% in 2006;[245] by 2011, however, the proportion had dropped slightly, to 14.8%.[245]

Rwanda has been a unified state since pre-colonial times,[43] and the population is drawn from just one cultural and linguistic group, the Banyarwanda;[246] this contrasts with most modern African states, whose borders were drawn by colonial powers and did not correspond to ethnic boundaries or pre-colonial kingdoms.[247] Within the Banyarwanda people, there are three separate groups, the Hutu, Tutsi and Twa.[248] The CIA World Factbook gives estimates that the Hutu made up 84% of the population in 2009, the Tutsi 15% and Twa 1%.[72] The Twa are a pygmy people who descend from Rwanda's earliest inhabitants, but scholars do not agree on the origins of and differences between the Hutu and Tutsi.[249] Anthropologist Jean Hiernaux contends that the Tutsi are a separate race, with a tendency towards "long and narrow heads, faces and noses";[250] others, such as Villia Jefremovas, believe there is no discernible physical difference and the categories were not historically rigid.[251] In precolonial Rwanda the Tutsi were the ruling class, from whom the kings and the majority of chiefs were derived, while the Hutu were agriculturalists.[252] The current government discourages the Hutu/Tutsi/Twa distinction, and has removed such classification from identity cards.[253] The 2002 census was the first since 1933[254] which did not categorise Rwandan population into the three groups.[255]

Education

Prior to 2012, the Rwandan government provided free education in state-run schools for nine years: six years in primary and three years following a common secondary programme.[256] In 2012, this started to be expanded to 12 years.[257] A 2015 study suggests that while enrollment rates in primary schools are "near ubiquity", rates of completion are low and repetition rates high.[258] While schooling is fee-free, there is an expectation that parents should contribute to the cost of their children's education by providing them with school supplies, supporting teacher development and making a contribution to school construction. According to the government, these costs should not be a basis for the exclusion of children from education, however.[257] There are many private schools across the country, some church-run, which follow the same syllabus but charge fees.[259] From 1994 until 2009, secondary education was offered in either French or English; because of the country's increasing ties with the East African Community and the Commonwealth, only the English syllabi are now offered.[260] The country has a number of institutions of tertiary education. In 2013, the public University of Rwanda (UR) was created out of a merger of the former National University of Rwanda and the country's other public higher education institutions.[261][262][263] In 2013, the gross enrollment ratio for tertiary education in Rwanda was 7.9%, from 3.6% in 2006.[264] The country's literacy rate, defined as those aged 15 or over who can read and write, was 78.8% in 2022, up from 71% in 2009, 58% in 1991, and 38% in 1978.[265][266]

Health

The quality of healthcare in Rwanda has historically been very low, both before and immediately after the 1994 genocide.[267] In 1998, more than one in five children died before their fifth birthday,[268] often from malaria.[269]

President Kagame has made healthcare one of the priorities for the Vision 2020 development programme,[270] boosting spending on health care to 6.5% of the country's gross domestic product in 2013,[271] compared with 1.9% in 1996.[272] The government has devolved the financing and management of healthcare to local communities, through a system of health insurance providers called mutuelles de santé.[273] The mutuelles were piloted in 1999, and were made available nationwide by the mid-2000s, with the assistance of international development partners.[273] Premiums under the scheme were initially US$2 per annum; since 2011 the rate has varied on a sliding scale, with the poorest paying nothing, and maximum premiums rising to US$8 per adult.[274] As of 2014, more than 90% of the population was covered by the scheme.[275] The government has also set up training institutes including the Kigali Health Institute (KHI), which was established in 1997[276] and is now part of the University of Rwanda. In 2005, President Kagame also launched a program known as The Presidents' Malaria Initiative.[277] This initiative aimed to help get the most necessary materials for prevention of malaria to the most rural areas of Rwanda, such as mosquito nets and medication.

In recent years Rwanda has seen improvement on a number of key health indicators. Between 2005 and 2013, life expectancy increased from 55.2 to 64.0,[278] under-5 mortality decreased from 106.4 to 52.0 per 1,000 live births,[279] and incidence of tuberculosis has dropped from 101 to 69 per 100,000 people.[280] The country's progress in healthcare has been cited by the international media and charities. The Atlantic devoted an article to "Rwanda's Historic Health Recovery".[281] Partners In Health described the health gains "among the most dramatic the world has seen in the last 50 years".[274]

Despite these improvements, however, the country's health profile remains dominated by communicable diseases,[282] and the United States Agency for International Development has described "significant health challenges",[283] including the rate of maternal mortality, which it describes as "unacceptably high",[283] as well as the ongoing HIV/AIDS epidemic.[283] According to the American Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, travellers to Rwanda are highly recommended to take preventive malaria medication as well as make sure they are up to date with vaccines such as yellow fever.[284]

Rwanda also has a shortage of medical professionals, with only 0.84 physicians, nurses, and midwives per 1,000 residents.[285] The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) is monitoring the country's health progress towards Millennium Development Goals 4–6, which relate to healthcare. A mid-2015 UNDP report noted that the country was not on target to meet goal 4 on infant mortality, despite it having "fallen dramatically";[286] the country is "making good progress" towards goal 5, which is to reduce by three quarters the maternal mortality ratio,[287] while goal 6 is not yet met as HIV prevalence has not started falling.[288]

Religion

The largest faith in Rwanda is Catholicism, but there have been significant changes in the nation's religious demographics since the genocide, with many conversions to evangelical Christianity, and, to a lesser degree, Islam.[289] According to the 2012 census, Catholic Christians represented 43.7% of the population, Protestants (excluding Seventh-day Adventists) 37.7%, Seventh-day Adventists 11.8%, and Muslims 2.0%; 0.2% claimed no religious beliefs and 1.3% did not state a religion.[290] Traditional religion, despite officially being followed by only 0.1% of the population, retains an influence. Many Rwandans view the Christian God as synonymous with the traditional Rwandan God Imana.[291]

Languages

The country's principal and national language is Kinyarwanda, which is virtually spoken by the entire country (98%).[292] The major European languages during the colonial era were German, though it was never taught or widely used, and then French, which was introduced by Belgium from 1916 and remained an official and widely spoken language after independence in 1962.[293] Dutch was spoken as well. The return of English-speaking Rwandan refugees in the 1990s[293] added a new dimension to the country's language policy,[294] and the repositioning of Rwanda as a member of the East African Community has since increased the importance of English; the medium of education was switched from French to English in 2008.[292] Kinyarwanda, English, French, and Swahili are all official languages.[295] Kinyarwanda is the national language while English is the primary medium of instruction in secondary and tertiary education. Swahili, the lingua franca of the East African Community,[296] is also spoken by some as a second language, particularly returned refugees from Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania, and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), and those who live along the border with the DRC.[297] In 2015, Swahili was introduced as a mandatory subject in secondary schools.[296] Inhabitants of Rwanda's Nkombo Island speak Mashi, a language closely related to Kinyarwanda.[298]

French was spoken by slightly under 6% of the population according to the 2012 census and the Organisation internationale de la Francophonie.[299] English was reported to be spoken by 15% of the population in 2009, though the same report found the proportion of French-speakers to be 68%.[292] Swahili is spoken by fewer than 1%.[300]

Human rights

Homosexuality is generally considered a taboo topic, and there is no significant public discussion of this issue in any region of the country. Some lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) Rwandans have reported being harassed and blackmailed.[301][302][303] Same-sex sexual activity is not specifically illegal in Rwanda. Some cabinet-level government officials have expressed support for the rights of LGBT people;[304] however, no special legislative protections are afforded to LGBT people,[302] who may be arrested by the police under various laws dealing with public order and morality.[303] Same-sex marriages are not recognized by the state, as the constitution provides that "[o]nly civil monogamous marriage between a man and a woman is recognized".[305]

Since 2006, Human Rights Watch has documented that Rwandan authorities round up and detain street children, street vendors, sex workers, homeless people, and beggars. They have also documented the use of torture in safe houses and other facilities, such as Kami military camp, Kwa Gacinya and Gikondo prison.[306]

Culture

Music and dance are an integral part of Rwandan ceremonies, festivals, social gatherings and storytelling. The most famous traditional dance is a highly choreographed routine consisting of three components: the umushagiriro, or cow dance, performed by women;[307] the intore, or dance of heroes, performed by men;[307] and the drumming, also traditionally performed by men, on drums known as ingoma.[308] The best-known dance group is the National Ballet. It was established by President Habyarimana in 1974, and performs nationally and internationally.[309] Traditionally, music is transmitted orally, with styles varying between the social groups. Drums are of great importance; the royal drummers enjoyed high status within the court of the King (Mwami).[310] Drummers play together in groups of varying sizes, usually between seven and nine in number.[311] The country has a growing popular music industry, influenced by African Great Lakes, Congolese, and American music. The most popular genre is hip hop, with a blend of dancehall, rap, ragga, R&B and dance-pop.[312]

Traditional arts and crafts are produced throughout the country, although most originated as functional items rather than purely for decoration. Woven baskets and bowls are especially common, notably the basket style of the agaseke.[313] Imigongo, a unique cow dung art, is produced in the southeast of Rwanda, with a history dating back to when the region was part of the independent Gisaka kingdom. The dung is mixed with natural soils of various colours and painted into patterned ridges to form geometric shapes.[314] Other crafts include pottery and wood carving.[315] Traditional housing styles make use of locally available materials; circular or rectangular mud homes with grass-thatched roofs (known as nyakatsi) are the most common. The government has initiated a programme to replace these with more modern materials such as corrugated iron.[316][317]

Rwanda does not have a long history of written literature, but there is a strong oral tradition ranging from poetry to folk stories. Many of the country's moral values and details of history have been passed down through the generations.[318] The most famous Rwandan literary figure was Alexis Kagame (1912–1981), who carried out and published research into oral traditions as well as writing his own poetry.[319] The Rwandan Genocide resulted in the emergence of a literature of witness accounts, essays and fiction by a new generation of writers such as Benjamin Sehene and Mfuranzima Fred. A number of films have been produced about the Rwandan Genocide, including the Golden Globe-nominated Hotel Rwanda, 100 Days, Shake Hands with the Devil, Sometimes in April, and Shooting Dogs, the last four having been filmed in Rwanda and having featured survivors as cast members.[320][321]

Fourteen regular national holidays are observed throughout the year,[322] with others occasionally inserted by the government. The week following Genocide Memorial Day on 7 April is designated an official week of mourning.[323] The victory for the RPF over the Hutu extremists is celebrated as Liberation Day on 4 July. The last Saturday of each month is umuganda, a national morning of mandatory community service lasting from 8 am to 11 am, during which all able bodied people between 18 and 65 are expected to carry out community tasks such as cleaning streets or building homes for vulnerable people.[324] Most normal services close down during umuganda, and public transportation is limited.[324]

Cuisine

The cuisine of Rwanda is based on local staple foods produced by subsistence agriculture such as bananas, plantains (known as ibitoke), pulses, sweet potatoes, beans, and cassava (manioc).[325] Many Rwandans do not eat meat more than a few times a month.[325] For those who live near lakes and have access to fish, tilapia is popular.[325] The potato, thought to have been introduced to Rwanda by German and Belgian colonialists, is very popular.[326] Ugali, locally known as Ubugari (or umutsima) is common, a paste made from cassava or maize and water to form a porridge-like consistency that is eaten throughout the African Great Lakes.[327] Isombe is made from mashed cassava leaves and can be served with dried fish, rice, ugali, potatoes etc.[326] Lunch is usually a buffet known as mélange, consisting of the above staples and sometimes meat.[328] Brochettes are the most popular food when eating out in the evening, usually made from goat but sometimes tripe, beef, or fish.[328]

In rural areas, many bars have a brochette seller responsible for tending and slaughtering the goats, skewering and barbecuing the meat, and serving it with grilled bananas.[329] Milk, particularly in a fermented yoghurt form called ikivuguto, is a common drink throughout the country.[330] Other drinks include a traditional beer called Ikigage made from sorghum and urwagwa, made from bananas, and a soft drink called Umutobe which is banana juice; these popular drinks feature in traditional rituals and ceremonies.[326] The major drinks manufacturer in Rwanda is Bralirwa, which was established in the 1950s, a Heineken partner, and is now listed on the Rwandan Stock Exchange.[331] Bralirwa manufactures soft drink products from The Coca-Cola Company, under licence, including Coca-Cola, Fanta, and Sprite,[332] and a range of beers including Primus, Mützig, Amstel, and Turbo King.[333] In 2009 a new brewery, Brasseries des Mille Collines (BMC) opened, manufacturing Skol beer and a local version known as Skol Gatanu;[334] BMC is now owned by Belgian company Unibra.[335] East African Breweries also operate in the country, importing Guinness, Tusker, and Bell, as well as whisky and spirits.[336]

Sport

The Rwandan government, through its Sports Development Policy, promotes sport as a strong avenue for "development and peace building",[338] and the government has made commitments to advancing the use of sport for a variety of development objectives, including education.[339] The most popular sports in Rwanda are association football, volleyball, basketball, athletics and Paralympic sports.[340] Cricket has been growing in popularity,[341] as a result of refugees returned from Kenya, where they had learned to play the game.[342] Cycling, traditionally seen largely as a mode of transport in Rwanda, is also growing in popularity as a sport;[343] and Team Rwanda have been the subject of a book, Land of Second Chances: The Impossible Rise of Rwanda's Cycling Team and a film, Rising from Ashes.[344][345]

Rwandans have been competing at the Olympic Games since 1984,[346] and the Paralympic Games since 2004.[347] The country sent seven competitors to the 2012 Summer Olympics in London, representing it in athletics, swimming, mountain biking and judo,[346] and 15 competitors to the London Summer Paralympics to compete in athletics, powerlifting and sitting volleyball.[347] The country has also participated in the Commonwealth Games since joining the Commonwealth in 2009.[348][349] The country's national basketball team has been growing in prominence since the mid-2000s, with the men's team qualifying for the final stages of the African Basketball Championship four times in a row since 2007.[350] The country bid unsuccessfully to host the 2013 tournament.[351][352] Rwanda's national football team has appeared in the African Cup of Nations once, in the 2004 edition of the tournament,[353] but narrowly failed to advance beyond the group stages.[354] The team have failed to qualify for the competition since, and have never qualified for the World Cup.[355] Rwanda's highest domestic football competition is the Rwanda National Football League;[356] as of 2015, the dominant team is APR FC of Kigali, having won 13 of the last 17 championships.[357] Rwandan clubs participate in the Kagame Interclub Cup for Central and East African teams, sponsored since 2002 by President Kagame.[358]

See also

Notes

- ^ UK: /ruˈændə/ ⓘ roo-AN-də, US: /ruˈɑːndə/ ⓘ roo-AHN-də;[13] Kinyarwanda: u Rwanda [u.ɾɡwaː.nda] ⓘ)[14]

Citations

- ^ "Rwanda: A Brief History of the Country". United Nations. Archived from the original on 15 July 2023. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

By 1994, Rwanda's population stood at more than 7 million people comprising 3 ethnic groups: the Hutu (who made up roughly 85% of the population), the Tutsi (14%), and the Twa (1%).

- ^ "Religions in Rwanda | PEW-GRF". globalreligiousfutures.org. Archived from the original on 23 May 2021. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- ^ a b Thomson, Susan (2018). Rwanda: From Genocide to Precarious Peace. Yale University Press. p. 185. ISBN 978-0-300-23591-3. Archived from the original on 22 October 2023. Retrieved 11 November 2023.

- ^ a b Sebarenzi, Joseph; Twagiramungu, Noel (8 April 2019). "Rwanda's economic growth could be derailed by its autocratic regime". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 5 September 2023. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- ^ a b Waldorf, Lars (2005). "Rwanda's failing experiment in restorative justice". Handbook of Restorative Justice. Routledge. p. ?. ISBN 978-0-203-34682-2.

- ^ a b Beswick, Danielle (2011). "Aiding State Building and Sacrificing Peace Building? The Rwanda–UK relationship 1994–2011". Third World Quarterly. 32 (10): 1911–1930. doi:10.1080/01436597.2011.610593. ISSN 0143-6597. S2CID 153404360.

- ^ a b Bowman, Warigia (2015). Four. Imagining a Modern Rwanda: Sociotechnological Imaginaries, Information Technology, and the Postgenocide State. University of Chicago Press. p. 87. doi:10.7208/9780226276663-004 (inactive 1 November 2024). ISBN 978-0-226-27666-3. Archived from the original on 5 September 2023. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ a b Reyntjens, Filip (2011). "Behind the Façade of Rwanda's Elections". Georgetown Journal of International Affairs. 12 (2): 64–69. ISSN 1526-0054. JSTOR 43133887. Archived from the original on 5 September 2023. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- ^ a b "Rwanda". The World Factbook (2025 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 6 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2023 Edition. (Rwanda)". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. 10 October 2023. Archived from the original on 19 October 2023. Retrieved 17 October 2023.

- ^ World Bank (XII).

- ^ "Human Development Report 2023/24". United Nations Development Programme. 13 March 2024. Archived from the original on 19 March 2024. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- ^ "Rwanda". Cambridge Dictionary. Archived from the original on 27 April 2024. Retrieved 6 December 2023.

- ^ "Government of Rwanda: Welcome to Rwanda". Archived from the original on 23 February 2021. Retrieved 22 February 2021.

- ^ Chrétien 2003, p. 44.

- ^ Dorsey 1994, p. 36.

- ^ Chrétien 2003, p. 45.

- ^ Schoenbrun, David L. (1993). "We Are What We Eat: Ancient Agriculture between the Great Lakes". The Journal of African History. 34 (1): 15–16. doi:10.1017/S0021853700032989. JSTOR 183030. S2CID 162660041.

- ^ Taylor, Christopher C. (13 September 2020). Sacrifice as Terror: The Rwandan Genocide of 1994. Routledge. pp. 63–65. ISBN 978-1-000-18448-8.

- ^ a b c Mamdani 2002, p. 61.

- ^ a b King 2007, p. 75.

- ^ Chrétien 2003, p. 58.

- ^ Prunier 1995, p. 16.

- ^ Mamdani 2002, p. 58.

- ^ Chrétien 2003, p. 69.

- ^ Shyaka, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Chrétien 2003, p. 88.

- ^ Chrétien 2003, pp. 88–89.

- ^ Chrétien 2003, p. 141.

- ^ Chrétien 2003, p. 482.

- ^ a b Chrétien 2003, p. 160.

- ^ a b c Mamdani 2002, p. 69.

- ^ Prunier 1995, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Prunier 1995, p. 6.

- ^ Chrétien 2003, p. 217.

- ^ Prunier 1995, p. 9.

- ^ Carney, J.J. (2013). Rwanda Before the Genocide: Catholic Politics and Ethnic Discourse in the Late Colonial Era. Oxford University Press. p. 24. ISBN 9780199982288. Archived from the original on 1 July 2023. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- ^ Prunier 1995, p. 25.

- ^ See also Helmut Strizek, "Geschenkte Kolonien: Ruanda und Burundi unter deutscher Herrschaft", Berlin: Ch. Links Verlag, 2006

- ^ Chrétien 2003, p. 260.

- ^ Chrétien 2003, p. 270.

- ^ Chrétien 2003, pp. 276–277.

- ^ a b Appiah & Gates 2010, p. 450.

- ^ Gourevitch 2000, pp. 56–57.

- ^ United Nations (II).

- ^ United Nations (III).

- ^ Linden & Linden 1977, p. 267.

- ^ Gourevitch 2000, pp. 58–59.

- ^ Prunier 1995, p. 51.

- ^ Prunier 1995, p. 53.

- ^ Karuhanga, James (30 June 2018). "Independence Day: Did Rwanda really gain independence on July 1, 1962?". The New Times. Archived from the original on 30 June 2018. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- ^ Prunier 1995, p. 56.

- ^ Prunier 1995, pp. 74–76.

- ^ a b UNPO 2008, History.

- ^ a b Prunier 1995, p. 4.

- ^ Prunier 1995, p. 93.

- ^ Prunier 1995, pp. 135–136.

- ^ Prunier 1995, pp. 190–191.

- ^ BBC News (III) 2010.

- ^ Henley 2007.

- ^ Dallaire 2005, p. 386.

- ^ Dallaire 2005, p. 299.

- ^ Dallaire 2005, p. 364.

- ^ Prunier 1995, p. 312.

- ^ a b BBC News (V) 2010.

- ^ Bowcott 2014.

- ^ World Bank (X).

- ^ a b World Bank (XI).

- ^ UNDP (I) 2010.

- ^ National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda 2012.

- ^ UNDP (V) 2013, p. 2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q CIA (I).

- ^ Stroh, Alexander (2010). "Electoral rules of the authoritarian game: undemocratic effects of proportional representation in Rwanda". Journal of Eastern African Studies. 4 (1): 1–19. doi:10.1080/17531050903550066. S2CID 154910536.

- ^ Matfess, Hilary (2015). "Rwanda and Ethiopia: Developmental Authoritarianism and the New Politics of African Strong Men". African Studies Review. 58 (2): 181–204. doi:10.1017/asr.2015.43. S2CID 143013060.

- ^ Waldorf, Lars (2017). "The Apotheosis of a Warlord: Paul Kagame". In Themnér, Anders (ed.). Warlord Democrats in Africa: Ex-Military Leaders and Electoral Politics (PDF). Bloomsbury Academic / Nordic Africa Institute. ISBN 978-1-78360-248-3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 November 2023. Retrieved 27 September 2023.

- ^ Clark 2010.

- ^ Panapress 2003.

- ^ CJCR 2003, article 52.

- ^ CJCR 2003, article 54.

- ^ CJCR 2003, article 98.

- ^ CJCR 2003, article 117.

- ^ a b CJCR 2003, article 110.

- ^ CJCR 2003, article 189.

- ^ CJCR 2003, article 112.

- ^ CJCR 2003, articles 100–101.

- ^ CJCR 2003, article 116.

- ^ CJCR 2003, article 62.

- ^ CJCR 2003, article 76.

- ^ CJCR 2003, article 140.

- ^ CJCR 2003, article 148.

- ^ Human Rights Watch & Wells 2008, I. Summary.

- ^ Human Rights Watch & Wells 2008, VIII. Independence of the Judiciary.

- ^ a b CJCR 2003, article 143.

- ^ Kamere 2011.

- ^ BBC News (VIII) 2015.

- ^ Walker & March 2004.

- ^ BBC News (IX) 2012.

- ^ Transparency International 2014.

- ^ Agutamba 2014.

- ^ CJCR 2003, article 182.

- ^ Office of the Ombudsman.

- ^ Asiimwe 2011.

- ^ Roth, Kenneth (10 December 2019). Rwanda Events of 2019. Human Rights Watch. Archived from the original on 14 April 2022. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- ^ United Nations (I).

- ^ Francophonie.

- ^ Grainger 2007.

- ^ Fletcher 2009.

- ^ Prunier 1995, p. 89.

- ^ Porter 2008.

- ^ Xinhua News Agency 2015.

- ^ USA Today 2008.

- ^ Al Jazeera 2007.

- ^ McGreal 2010.

- ^ BBC News (X) 2012.

- ^ Agence Africaine de Presse 2015.

- ^ Heuler 2011.

- ^ BBC News (VI) 2011.

- ^ Maboja 2015.

- ^ Malingha, David (8 March 2019). "Why a Closed Border Has Uganda, Rwanda at Loggerheads". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 20 April 2019. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ^ Butera, Saul; Ojambo, Fred (21 February 2020). "Uganda, Rwanda Hold Talks On Security Concerns, Reopening Border". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 6 March 2020. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ^ OAU 2000, p. 14.

- ^ Melvern 2004, p. 5.

- ^ CJCR 2003, article 3.

- ^ Gwillim Law (27 April 2010). "Rwanda Districts". www.statoids.com. Archived from the original on 21 August 2020. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ BBC News (I) 2006.

- ^ a b MINALOC 2007, p. 8.

- ^ Southern Province.

- ^ a b MINALOC 2007, p. 9.

- ^ a b MINALOC 2004.

- ^ a b CIA (II).

- ^ Richards 1994.

- ^ a b c d U.S. Department of State 2004.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica 2010.

- ^ Nile Basin Initiative 2010.

- ^ BBC News (II) 2006.

- ^ Jørgensen 2005, p. 93.

- ^ Briggs & Booth 2006, p. 153.

- ^ Hodd 1994, p. 522.

- ^ Christophe Migeon. "Voyage au Rwanda, le pays des Mille Collines Archived 7 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine" (In French), Le Point, 26 May 2018. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ^ a b WWF 2001, Location and General Description.

- ^ Mehta & Katee 2005, p. 37.

- ^ Munyakazi & Ntagaramba 2005, p. 7.

- ^ Munyakazi & Ntagaramba 2005, p. 18.

- ^ World Meteorological Organization.

- ^ Best Country Reports 2007.

- ^ King 2007, p. 10.

- ^ Adekunle 2007, p. 1.

- ^ a b Strategic Foresight Group 2013, p. 29.

- ^ Bucyensenge 2014.

- ^ a b Briggs & Booth 2006, pp. 3–4.

- ^ King 2007, p. 11.

- ^ REMA (Chapter 5) 2009, p. 3.

- ^ "Climate Change Adaption in Rwanda" (PDF). USAID. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 February 2022. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- ^ Government of Rwanda (II).

- ^ RDB (III).

- ^ RDB (I) 2010.

- ^ Briggs & Booth 2006, p. 140.

- ^ Smith 2015.

- ^ The New Times 2015.

- ^ "Black rhinos return to Rwanda 10 years after disappearance". The Guardian. Agence France-Presse. 3 May 2017. Archived from the original on 29 November 2022. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- ^ "Rwanda Just Pulled Off the Largest Transport of Rhinos From Europe to Africa". Condé Nast Traveler. 26 June 2019. Archived from the original on 17 December 2022. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- ^ "White rhinos flown from South Africa to Rwanda in largest single translocation". The Guardian. 29 November 2021. Archived from the original on 17 December 2022. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- ^ Hernandez, Joe (30 November 2021). "Conservationists flew 30 white rhinos to Rwanda in a huge operation to protect them". Archived from the original on 17 December 2022. Retrieved 17 December 2022 – via NPR.

- ^ a b c King 2007, p. 15.

- ^ WCS.

- ^ Tedrow 2015.

- ^ Maynard 2014.

- ^ Dinerstein, Eric; et al. (2017). "An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm". BioScience. 67 (6): 534–545. doi:10.1093/biosci/bix014. ISSN 0006-3568. PMC 5451287. PMID 28608869.

- ^ Grantham, H.S.; et al. (2020). "Anthropogenic modification of forests means only 40% of remaining forests have high ecosystem integrity – Supplementary Material". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 5978. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.5978G. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-19493-3. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 7723057. PMID 33293507.

- ^ "World Economic Outlook database: April 2022". International Monetary Fund. Archived from the original on 31 May 2022. Retrieved 2 May 2022.

- ^ IMF (I).

- ^ "Multidimensional Poverty Index 2023 Rwanda" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme Human Development Reports. 2023. Retrieved 5 August 2024.

- ^ "USD–RWF 2023 Yahoo". freecurrencyrates.com. Archived from the original on 17 May 2024. Retrieved 17 May 2024.

- ^ Asiimwe 2014.

- ^ Lavelle 2008.

- ^ FAO / WFP 1997.

- ^ a b c d Our Africa.

- ^ WRI 2006.

- ^ "From genocide to growth: Rwanda's remarkable economic turnaround – GE63". 24 March 2023. Archived from the original on 31 March 2023. Retrieved 31 March 2023.

- ^ "Rwanda production in 2019, by FAO". The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Archived from the original on 11 May 2017. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ Tumwebaze 2016.

- ^ WTO 2004.

- ^ a b MINAGRI 2006.

- ^ Namata 2008.

- ^ a b Mukaaya 2009.

- ^ Delawala 2001.

- ^ a b Nantaba 2010.

- ^ Mukaaya 2008.

- ^ Nielsen & Spenceley 2010, p. 6.

- ^ a b KT Press 2015.

- ^ Nielsen & Spenceley 2010, p. 2.

- ^ RDB (II).

- ^ World Intellectual Property Organization (2024). Global Innovation Index 2024. Unlocking the Promise of Social Entrepreneurship. Geneva. p. 18. doi:10.34667/tind.50062. ISBN 978-92-805-3681-2. Retrieved 22 October 2024.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d BBC News (VII) 2015.

- ^ Gasore 2014.

- ^ Opobo 2015.

- ^ Reporters Without Borders 2010.

- ^ Mugisha 2013.

- ^ Southwood 2013.

- ^ Mugwe 2013.

- ^ a b RURA 2015, p. 6.

- ^ Majyambere 2010.

- ^ a b RURA 2015, p. 5.

- ^ RURA 2011, p. 3.

- ^ Butera 2011.

- ^ World Bank (II).

- ^ a b Reuters 2011.

- ^ Butera 2010.

- ^ "Rwanda launches first 'Made in Africa' smartphones". Reuters. 10 October 2019. Archived from the original on 9 October 2019. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- ^ a b IDA 2009.

- ^ a b c Umutesi 2015.

- ^ MINECOFIN 2002, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Berry, Lewis & Williams 1990, p. 533.

- ^ a b c USAID (I) 2008, p. 3.

- ^ Rwanda, UNICEF (April 2024). "Water, Sanitation and Hygiene(WASH) Budget Brief" (PDF). unicef.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 May 2024. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ "Should You Visit Kigali? A look at the cleanest city in Africa". Burdie.co. 1 April 2019. Archived from the original on 15 January 2021. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- ^ World Resources Report 2011, p. 3.

- ^ a b c World Resources Report 2011, p. 5.

- ^ AfDB 2011.

- ^ World Bank (XIII).

- ^ Baringanire, Malik & Banerjee 2014, p. 1.

- ^ AfDB & OECD Development Centre 2006, p. 439.

- ^ Tancott 2014.

- ^ a b c MININFRA 2013, p. 34.

- ^ MININFRA 2013, p. 67.

- ^ MININFRA 2013, p. 32.

- ^ a b Centre For Aviation 2014.

- ^ Tumwebaze 2015.

- ^ MININFRA 2017.

- ^ Senelwa 2015.

- ^ a b MININFRA 2013, p. 43.

- ^ "Rwanda Cities by Population". Archived from the original on 21 June 2023. Retrieved 21 June 2023.

- ^ a b National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda 2015.

- ^ National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda. "Size of the resident population". National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda. Archived from the original on 2 June 2022. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- ^ National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda 2014, p. 3.

- ^ National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda 2014, p. 8.

- ^ CIA (III) 2011.

- ^ Banda 2015.

- ^ Straus 2013, p. 215.

- ^ Streissguth 2007, p. 11.

- ^ Kigali City.

- ^ a b Percival & Homer-Dixon 1995.

- ^ REMA (Chapter 2) 2009.

- ^ a b City Population 2012.

- ^ a b National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda 2012, p. 29.

- ^ Mamdani 2002, p. 52.

- ^ Boyd 1979, p. 1.

- ^ Prunier 1995, p. 5.

- ^ Mamdani 2002, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Mamdani 2002, p. 47.

- ^ Jefremovas 1995.

- ^ Prunier 1995, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Coleman 2010.

- ^ Kiwuwa 2012, p. 71.

- ^ Agence France-Presse 2002.

- ^ MINEDUC 2010, p. 2.

- ^ a b Williams, Abbott & Mupenzi 2015, p. 935.

- ^ Williams, Abbott & Mupenzi 2015, p. 931.

- ^ Briggs & Booth 2006, p. 27.

- ^ McGreal 2009.

- ^ Koenig 2014.

- ^ MacGregor 2014.

- ^ Rutayisire 2013.

- ^ World Bank (III).

- ^ World Bank (I).

- ^ "Rwanda adult literacy rate, 1960-2023". Knoema. Retrieved 5 August 2024.

- ^ Drobac & Naughton 2014.

- ^ World Bank (IV).

- ^ Bowdler 2010.

- ^ Evans 2014.

- ^ World Bank (V).

- ^ World Bank (VI).

- ^ a b WHO 2008.

- ^ a b Rosenberg 2012.

- ^ USAID (II) 2014.

- ^ IMF 2000, p. 34.

- ^ "HIV/AIDS, Malaria and other diseases". United Nations in Rwanda. Archived from the original on 15 May 2016. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- ^ World Bank (VII).

- ^ World Bank (VIII).

- ^ World Bank (IX).

- ^ Emery 2013.

- ^ WHO 2015.

- ^ a b c USAID (III) 2015.