Ruthenians

A boy with the pilgrimage flag with the Ruthenian lion during the Ruthenian pilgrimage to the Holy Land in 1906 | |

| Languages | |

|---|---|

| |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Eastern Orthodox Ruthenian Greek Catholic, Ukrainian Greek Catholic, Russian Greek Catholic Church among other Byzantine rites originally from Slavic origins. | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other East Slavs |

Ruthenian and Ruthene are exonyms of Latin origin, formerly used in Eastern and Central Europe as common ethnonyms for Ukrainians and partially Belarusians, particularly during the late medieval and early modern periods. The Latin term Rutheni was used in medieval sources to describe Eastern Slavs of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, as an exonym for people of the former Kievan Rus', thus including ancestors of the modern Belarusians, Rusyns and Ukrainians.[1][2] The use of Ruthenian and related exonyms continued through the early modern period, developing several distinctive meanings, both in terms of their regional scopes and additional religious connotations (such as affiliation with the Ruthenian Greek Catholic Church).[1][3][4][5][6]

In medieval sources, the Latin term Rutheni was commonly applied to East Slavs in general, thus encompassing all endonyms and their various forms (Belarusian: русіны, romanized: rusiny; Ukrainian: русини, romanized: rusyny). By opting for the use of exonymic terms, authors who wrote in Latin were relieved from the need to be specific in their applications of those terms, and the same quality of Ruthenian exonyms is often recognized in modern, mainly Western authors, particularly those who prefer to use exonyms (foreign in origin) over endonyms.[7][8][9]

During the early modern period, the exonym Ruthenian was most frequently applied to the East Slavic population of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, an area encompassing territories of modern Belarus and Ukraine from the 15th up to the 18th centuries.[10][11] In the former Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, the same term (German: Ruthenen) was employed up to 1918 as an official exonym for the entire Ukrainian population within the borders of the Monarchy.[12][13]

Etymology

Ruteni, a misnomer that was also the name of an extinct and unrelated Celtic tribe in Ancient Gaul,[7] was used in reference to Rus' in the Annales Augustani of 1089.[7] An alternative early modern Latinisation, Rucenus (plural Ruceni) was, according to Boris Unbegaun, derived from Rusyn.[7] Baron Herberstein, describing the land of Russia (Rus'), inhabited by the Rutheni who call themselves Russi, claimed that the first of the governors who rule Russia (Rus') is the Grand Duke of Moscow, the second is the Grand Duke of Lithuania and the third is the King of Poland.[14][15]

According to professor John-Paul Himka from the University of Alberta the word Rutheni did not include the modern Russians, who were known as Moscovitae throughout Western Europe.[7][16] Vasili III of Russia, who ruled the Grand Duchy of Moscow in the 16th century, was known in European Latin sources as Rhuteni Imperator, do to a self proclaimed title "Tsar of Rus' (Russia)".[17] Jacques Margeret in his book "Estat de l'empire de Russie, et grande duché de Moscovie" of 1607 said that the name "Muscovites" for the population of Tsardom (Empire) of Russia is an error.[citation needed] During conversations, they called themselves rusaki (which is a colloquial term for Russians) and only the citizens of the capital called themself "Muscovites". Margeret considered that this error is worse than calling all the French "Parisians".[18][19] Professor David Frick from the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute has also found in Vilnius the documents from 1655, which demonstrate that Moscovitae were sometimes referred in Lithuania as Rutheni (as former part of Kievan Rus').[20] The 16th century Portuguese poet Luís Vaz de Camões in his Os Lusíadas" (Canto III, 11)[21][22] clearly writes "...Entre este mar e o Tánais vive estranha Gente: Rutenos, Moscos e Livónios, Sármatas outro tempo..." differentiating between Ruthenians and Muscovites.

Ruthenians of different regions in 1836:

- 1, 2. Galician Ruthenians;

- 3. Carpathian Ruthenians;

- 4, 5. Podolian Ruthenians.

After the partition of Poland, the term Ruthenian referred exclusively to people of the Rusyn- and Ukrainian-speaking areas of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, especially in the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria, Bukovina, and Transcarpathia.[7]

At the request of Mykhailo Levytsky, in 1843, the term Ruthenian became the official name for the Rusyns and Ukrainians within the Austrian Empire.[7] For example, Ivan Franko and Stepan Bandera in their passports were identified as Ruthenians (Polish: Rusini).[23] By 1900, more and more Ruthenians began to call themselves with the self-designated name Ukrainians.[7] With the emergence of Ukrainian nationalism during the mid-19th century, use of "Ruthenian" and cognate terms declined among Ukrainians and fell out of use in Eastern and Central Ukraine. Most people in the western region of Ukraine followed suit later in the 19th century. During the early 20th century, the name Ukrajins'ka mova ("Ukrainian language") became accepted by much of the Ukrainian-speaking literary class in the Austro-Hungarian Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria.[citation needed]

Following the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1918, new states emerged and dissolved; borders changed frequently. After several years, the Rusyn and Ukrainian speaking areas of eastern Austria-Hungary found themselves divided between the Czechoslovakia, Poland, and Romania.

When commenting on the partition of Czechoslovakia by Nazi Germany in March 1939, US diplomat George Kennan noted, "To those who inquire whether these peasants are Russians or Ukrainians, there is only one answer. They are Neither. They are simply Ruthenians."[24] Dr. Paul R. Magocsi emphasizes that modern Ruthenians have "the sense of a nationality distinct from Ukrainians" and often associate Ukrainians with Soviets or Communists.[25]

After the expansion of Soviet Ukraine following World War II, several groups who had not previously considered themselves Ukrainians were merged into the Ukrainian identity.[26]

Ruthenian terminology in Poland

In the interbellum period of the 20th century, the term rusyn (Ruthenian) was also applied to people from the Kresy Wschodnie (the eastern borderlands) in the Second Polish Republic, and included Ukrainians, Rusyns, and Lemkos, or alternatively, members of the Uniate or Greek Catholic Churches. In Galicia, the Polish government actively replaced all references to "Ukrainians" with the old word rusini ("Ruthenians").

The Polish census of 1921 considered Ukrainians no other than Ruthenians, meanwhile Belarusians have already become a separate nation, which in Polish is literally translated as "White Ruthenians" (Polish: Białorusini).[27] However the Polish census of 1931 counted Belarusian, Ukrainian, and Rusyn as separate language categories, and the census results were substantially different from before.[28] According to Rusyn-American historian Paul Robert Magocsi, Polish government policy in the 1930s pursued a strategy of tribalization, regarding various ethnographic groups—i.e., Lemkos, Boykos, and Hutsuls, as well as Old Ruthenians and Russophiles—as different from other Ukrainians and offered instructions in Lemko vernacular in state schools set up in the westernmost Lemko Region.[29][28]

The Polish census of 1931 listed "Belarusian", "Rusyn" and "Ukrainian" (Polish: białoruski, ruski, ukraiński, respectively) as separate languages.[30][31]

Carpatho-Ruthenian ethnonyms

By the end of the 19th century, another set of terms came into use in several western languages, combining regional Carpathian with Ruthenian designations, and thus producing composite terms such as: Carpatho-Ruthenes or Carpatho-Ruthenians. Those terms also acquired several meanings, depending on the shifting geographical scopes of the term Carpathian Ruthenia. Those meanings were also spanning from wider uses as designations for all East Slavs of the Carpathian region, to narrower uses, focusing on those local groups of East Slavs who did not accept a modern Ukrainian identity, but rather opted to keep their traditional Rusyn identity.[32]

The designations Rusyn and Carpatho-Rusyn were banned in the Soviet Union by the end of World War II in June 1945.[26] Ruthenians who identified under the Rusyn ethnonym and considered themselves to be a national and linguistic group separate from Ukrainians and Belarusians were relegated to the Carpathian diaspora and formally functioned among the large immigrant communities in the United States.[25][26] A cross-European revival took place only with the collapse of communist rule in 1989.[26] This has resulted in political conflict and accusations of intrigue against Rusyn activists, including criminal charges. The Rusyn minority is well represented in Slovakia. The single category of people who listed their ethnicity as Rusyn was created in the 1920s; however, no generally accepted standardised Rusyn language existed.[33]

After World War II, following the practice in the Soviet Union, Ruthenian ethnicity was disallowed. This Soviet policy maintained that the Ruthenians and their language were part of the Ukrainian ethnic group and language. At the same time, the Greek Catholic church was banned and replaced with the Eastern Orthodox church under the Russian Patriarch, in an atmosphere which repressed all religions. Thus, in Slovakia, the former Ruthenians were technically free to register as any ethnicity but Ruthenian.[33]

The government of Slovakia has proclaimed Rusyns (Rusíni) to be a distinct national minority (1991) and recognised Rusyn language as a distinct language (1995).[7]

Speculative theories

Since the 19th century, several speculative theories emerged regarding the origin and nature of medieval and early modern uses of Ruthenian terms as designations for East Slavs. Some of those theories were focused on a very specific source, a memorial plate from 1521, that was placed in the catacombe Chapel of St Maximus in Petersfriedhof, the burial site of St Peter's Abbey in Salzburg (modern Austria). The plate contains Latin inscription that mentions Italian ruler Odoacer (476–493) as king of "Rhutenes" or "Rhutenians" (Latin: Rex Rhvtenorvm), and narrates a story about the martyrdom of St Maximus during an invasion of several peoples into Noricum in 477. Due to the very late date (1521) and several anachronistic elements, the content of that plate is considered as legendary.[34][35]

In spite of that, some authors (mainly non-scholars) employed that plate as a "source" for several theories that were trying to connect Odoacer with ancient Celtic Ruthenes from Gaul, thus also providing an apparent bridge towards later medieval authors who labeled East Slavs as Ruthenes or Ruthenians. On those bases, an entire strain of speculative theories was created, regarding the alleged connection between ancient Gallic Ruthenes and later East Slavic "Ruthenians".[36] As noted by professor Paul R. Magocsi, those theories should be regarded as "inventive tales" of "creative" writers.[37][38]

Geography

From the 9th century, Kievan Rus' – now part of the modern states of Ukraine, Belarus and Russia – was known in Western Europe by a variety of names derived from Rus'. From the 12th century, the land of Rus' was usually known in Western Europe by the Latinised name Ruthenia.[citation needed][dubious – discuss]

- Kievan Rus', also known as Ruthenia, c. 1230

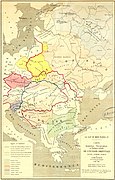

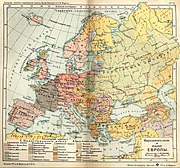

- 1868 linguistic, ethnographic, and political map of Eastern Europe by Casimir DelamarreRuthenians and Ruthenian language

- 1907 linguistic and ethnographic map that indicates Ukrainians as "Little Russians or Ruthenians"

- 1911 map depicting the Austro-Hungarian Empire, with Ruthenians in light green

- 1927 Polish map that indicates Ukrainians as "Ruthenians" ("Rusini"), and Belarusians as "White Ruthenians" ("Białorusini")

- 1918 map of Ukraine. Caption says following: "In the ruled area Ukrainian (Ruthenian) speech predominates…"

Ruthenian culture

Language

The Ruthenian language (Ruthenian: рускаꙗ мова, рускїй ѧзыкъ) was an exonymic linguonym for a closely related group of East Slavic linguistic varieties, particularly those spoken from the 15th to 18th centuries in the East Slavic regions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. By the end of the 18th century, they gradually diverged into regional variants, which subsequently developed into the modern Belarusian (White Ruthenian), Ukrainian (Ruthenian), and Rusyn (Carpathian Ruthenian) languages.[40][41]

Religions

With the baptism of Volodymyr began a long history of the dominance of Eastern Orthodoxy in Ruthenia. The Rus' accepted Christianity in its Byzantine form at the same time as the Poles accepted it in its Latin form, Lithuanians largely remained pagan to the late Middle Ages before their nobility embraced the Latin form upon the political union with the Poles. The eastward expansion of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania had been facilitated by amicable treaties and inter-marriages of the nobility when faced with the external threat of the Mongol invasion of Kievan Rus'.

By the end of the 12th century, Europe was generally divided into two large areas: Western Europe with dominance of Catholicism, and Eastern Europe with Orthodox and Byzantine influences. The border between them was roughly marked by the Bug River. This placed the area now known as Belarus in a unique position where these two influences mixed and interfered.

The first Latin Church diocese in White Ruthenia was established in Turaŭ between 1008 and 1013. Catholicism was a traditionally dominant religion of Belarusian nobility (the szlachta) and of a large part of the population of western and northwestern parts of Belarus. Before the 14th century, the Eastern Orthodox Church was dominant in White Ruthenia. The Union of Krewo in 1385 broke this monopoly and made Catholicism the religion of the ruling class.

Jogaila, then ruler of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, ordered the whole population of Lithuania to convert to Catholicism. One and a half years after the Union of Krewo, the Wilno (Vilnius) episcopate was created which received a lot of land from the Lithuanian dukes. By the mid-16th century Catholicism became strong in Lithuania and bordering with it north-west parts of White Ruthenia, but the Orthodox church was still dominant.

In the 14th century, Emperor Andronikos II Palaiologos sanctioned the creation of two additional metropolitan sees: the Metropolis of Halych (1303) and the Metropolis of Lithuania (1317).

Metropolitan Roman (1355–1362) of Lithuania and Metropolitan Alexius of Kiev both claimed the see. Both metropolitans travelled to Constantinople to make their appeals in person. In 1356, their cases were heard by a Patriarchal Synod. The Holy Synod confirmed that Alexis was the Metropolitan of Kiev while Roman was also confirmed in his see at Novogorodek. In 1361, the two sees were formally divided. Shortly afterwards, in the winter of 1361/62, Roman died. From 1362 to 1371, the vacant see of Lithuania–Halych was administered by Alexius. By that point, the Lithuanian metropolis was effectively dissolved.

Following the signing of the Council of Florence, Metropolitan Isidore of Kiev returned to Moscow in 1441 as a Ruthenian cardinal. He was arrested by the Grand Duke of Moscow and accused of apostasy. The Grand Duke deposed Isidore and in 1448 installed own candidate as Metropolitan of Kyiv — Jonah. This was carried out without the approval of Patriarch Gregory III of Constantinople. When Isidore died in 1458, he was succeeded as metropolitan in the Patriarchate of Constantinople by Gregory the Bulgarian. Gregory's canonical territory was the western part of the traditional Kievan Rus' lands — the states of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Kingdom of Poland. The episcopal seat was in the city of Navahrudak which is today located in Belarus. It was later moved to Vilnius — the capital of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. A parallel succession to the title ensued between Moscow and Vilnius. The Metropolitans of Kiev are the predecessors of the Patriarch of Moscow and all Rus' that was formed in the 16th century.

The Ruthenian Uniate Church was created in 1595–1596 by those clergy of the Eastern Orthodox churches who subscribed to the Union of Brest. In the process, they switched their allegiances and jurisdiction from the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople to the Holy See. It had a single metropolitan territory — the Metropolis of Kiev, Galicia and all Ruthenia. The formation of the church led to a high degree of confrontation among Ruthenians, such as the murder of the hierarch Josaphat Kuntsevych in 1623. Opponents of the union called church members "Uniates", although Catholic documents no longer use the term due to its perceived negative overtones. In 1620, these dissenters erected their own metropolis — the "Metropolis of Kyev, Galicia and all Ruthenia".

In the 16th century, a crisis began in Christianity: the Protestant Reformation began in Catholicism and a period of heresy began in an Orthodox area. From the mid-16th century Protestant ideas began spreading in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. The first Protestant Church in Belarus was created in Brest by Mikołaj "the Black" Radziwiłł. Protestantism did not survive due to the Counter-Reformation in Poland.

Both the Catholic Church in the Commonwealth and the Ruthenian Church underwent a period of decay. The Ruthenian Church was the church of a people without statehood. The Poles considered the Ruthenians a conquered people. Over time, the Lithuanian military and political ascendancy did away with the Ruthenian autonomies. The disadvantageous political status of the Ruthenian people also affected the status of their church and undermined her capacity for reform and renewal. Furthermore, they could not expect support from the Mother Church in Constantinople or from their co-religionists in Moscow. Thus, the Ruthenian church was in a weaker position than the Catholic Church in the Commonwealth.

Until 1666, when Patriarch Nikon was deposed by the tsar, the Russian Orthodox Church had been independent of the State. In 1721, the first Russian Emperor, Peter I, abolished completely the patriarchate and effectively made the church a department of the government, ruled by the Most Holy Synod composed of senior bishops and lay bureaucrats appointed by the emperor himself. Over time, Imperial Russia would style itself a protector and patron of all Orthodox Christians, especially those within the Ottoman Empire.

Domination of tsarist-ruled Ukraine by the Russian Empire (from 1721) eventually led to the decline of Uniate Catholicism (officially founded in 1596) in the Ukrainian lands under Tsarist control.

Music and Dance

Musical scores titled "Baletto Ruteno" or "Horea Rutenia", meaning Ruthenian Ballet can be found in European collections during the Lithuanian and Polish rule of Ruthenia, such as the Gdańsk lute tablature of 1640.[42][43]

Symbols

- Flag of the Cossack Hetmanate used since the 17th century

- Coat of Arms of Ruthenian Voivodeship from Stematographia (1701)

- Coat of arms for the proposed Pol.–Lith.–Ruth. Commonwealth, which never came into being. It consisted of the Polish White Eagle, the Lithuanian Pahonia and the Ruthenian Archangel Michael (19th century)

- Coat of arms of the Jełowicki noble family

- Coat of arms of the Sapieha noble family

- Coat of arms of the Ostrogski noble family

- Coat of arms of the Ogiński noble family

- Coat of arms of the Pac noble family

- Coat of arms of the Chodkiewicz noble family

- Coat of arms of the Radziwiłł noble family

- Coat of arms of the Doroshenko noble family

- Coat of arms of the Khanenko noble family

- Coat of arms of the Teteria noble family

- Coat of arms of the Polubotok noble family

- Coat of arms of the Vyhovsky noble family

Notable Ruthenian people

- Volodymyr the Great (c. 958–1015), Grand Prince of Kiev, Ruthenian saint, Christianizer of Kievan Rus'

- Yaroslav the Wise (c. 978–1054), Grand Prince of Kiev, under which Kievan Rus' reached its territorial peak and golden age

- Volodymyr Monomakh (1053–1125), Grand Prince of Kiev, who kept the Kievan Rus' together and protected Rus' land from nomadic incursions

- Danylo of Galicia (1201–1264), prince of Galicia-Volhynia, Grand Prince of Kiev and the first King of Ruthenia

- Konstanty Ostrogski (c. 1460–1530), a Ruthenian prince and magnate of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Ruthenia, Samogitia and later a Grand Hetman of Lithuania

- Roxelana (c. 1504–1558), also known as Haseki Hürrem Sultan, wife of Suleiman the Magnificent

- Meletius Smotrytsky (c. 1577–1633), an archbishop of Polotsk, writer, religious and pedagogical activist of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and Ruthenian linguist[44]

- Bohdan Khmelnytsky (c. 1595–1657), a Ruthenian nobleman, military commander of Zaporozhian Cossacks, leader of the Khmelnytsky Uprising and founding father of the Cossack Hetmanate

- Ivan Mazepa (c. 1639–1709), the Hetman of the Cossack Hetmanate, patron of arts, under which rule Hetmanate was reunited and prospered, marking the end of its Ruin age

- Petro Doroshenko (c. 1595–1657), a Cossack political and military leader, Hetman of Right-bank Ukraine (1665–1672)[45]

See also

- American Carpatho-Ruthenian Orthodox Diocese

- Coat of arms of Carpathian Ruthenia

- Names of Rus', Russia and Ruthenia

- Polish–Lithuanian–Ruthenian Commonwealth

- Cossack Hetmanate

- Ruthenian Greek Catholic Church

- Ruthenian nobility

- Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church

- Galician Russophilia

References

- ^ a b Paul Robert Magocsi. "Rusyn". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

- ^ РУСИНЫ [Rusyns]. Большая российская энциклопедия - электронная версия (in Russian). [Great Russian Encyclopedia - electronic version]. Archived from the original on 26 September 2021. Retrieved 15 December 2021.

- ^ Shipman 1912a, p. 276-277.

- ^ Shipman 1912b, p. 277-279.

- ^ Krajcar 1963, p. 79-94.

- ^ Rohdewald, Stefan; Frick, David A.; Wiederkehr, Stefan (2007). Litauen und Ruthenien: Studien zu einer transkulturellen Kommunikationsregion (15.–18. Jahrhundert) [Lithuania and Ruthenia: studies of a transcultural communication zone (15th–18th centuries)] (in German). Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. p. 22. ISBN 978-3-447-05605-2. OCLC 173071153.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Himka, John-Paul. "Ruthenians". Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine.

- ^ Himka 1999, p. 8-9.

- ^ Magocsi 2015, p. 2-5.

- ^ Bunčić 2015, p. 276-289.

- ^ Statute of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (1529), Part. 1., Art. 1.: "На первей преречоным прелатом, княжатом, паном, хоруговым, шляхтам и местом преречоных земель Великого князства Литовского, Руского, Жомойтского и иных дали есмо: ..."; According to.: Pervyi ili Staryi Litovskii Statut // Vremennik Obschestva istorii i drevnostei Rossiiskih. 1854. Book 18, p. 2.

- ^ Moser 2017–2018, p. 87-104.

- ^ "Magyarország népessége". mek.oszk.hu. Retrieved 24 October 2023.

- ^ Sigismund von Herberstein Rerum Moscoviticarum Commentarii

- ^ Myl'nikov 1999, p. 46.

- ^ Speake, Jennifer, ed. (2003). "Muscovy". Literature of travel and exploration: An encyclopedia. Volume Two: G to P. New York: Fitzroy Dearborn. pp. 831–834. ISBN 978-1-57958-247-0.

- ^ Лобин А. Н. Послание государя Василия III Ивановича императору Карлу V от 26 июня 1522 г.: Опыт реконструкции текста // Studia Slavica et Balcanica Petropolitana, № 1. Санкт-Петербург, 2013. C. 131.

- ^ Dunning, Chester (15 June 1983). The Russian Empire and Grand Duchy of Muscovy: A Seventeenth-Century French Account. University of Pittsburgh Press. pp. 7, 106. ISBN 978-0-8229-7701-8.

- ^ Myl'nikov 1999, p. 84.

- ^ Frick, David (2005). "The Councilor and the baker's wife: Ruthenians and their language in seventeenth-century Vilnius". In Vyacheslav V. Ivanov; Julia Verkholantsev (eds.). Speculum Slaviae Orientalis: Muscovy, Ruthenia and Lithuania in the late Middle ages. UCLA Slavic studies; new series (in English and Russian). Vol. IV. Moscow: Новое изд-во : Novoe izdatel'stvo. pp. 45–67. ISBN 9785983790285.

- ^ Fabio Renato Villela. Os Lusíadas, Canto III, 11. Adaptação De Os LusÍadas Ao Português Atual.

- ^ Luís de Camões «Os Lusíadas. Canto Terceiro». www.tania-soleil.com.

- ^ Panayir, D. (16 February 2011). "Москвофільство. Як галичани вчили росіян любити Росію" [Moscowphilia. How Galicians taught Russians to love Russia.] Istorychna Pravda (Ukrayinska Pravda); (in Ukrainian)

- ^ Report on Conditions in Ruthenia March 1939, From Prague After Munich: Diplomatic Papers 1938-1940, (Princeton University Press, 1968)

- ^ a b Magocsi 1995, p. 221-231.

- ^ a b c d Paul Robert Magocsi. "Rusyn". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

Today the name Rusyn refers to the spoken language and variants of a literary language codified in the 20th century for Carpatho-Rusyns living in Ukraine (Transcarpathia), Poland, Slovakia, Hungary, and Serbia (the Vojvodina). ... Subcarpathian Rus was ceded by Czechoslovakia to the Soviet Union and became the Transcarpathian oblast (region) of the Ukrainian S.S.R. The designations Rusyn and Carpatho-Rusyn were banned, and the local East Slavic inhabitants and their language were declared to be Ukrainian. Soviet policy was followed in neighbouring communist Czechoslovakia and Poland, where the Carpatho-Rusyn inhabitants (Lemko Rusyns in the case of Poland) were henceforth officially designated Ukrainians

- ^ Główny Urząd Statystyczny [Central Statistical Office] (1932). "Ludnosc: Ludnosc wedlug wyznania religijnego i narodowosci" [Population: Population by religious denomination and nationality]. Polish Census 1931 p. 56, table 11. (in Polish)

- ^ a b Główny Urząd Statystyczny [Central Statistical Office] "Ludnosc. Ludnosc wedlug wyznania i plci oraz jezyka ojczystego" [Population: Population by religion, gender and native language]. Polish Census 1931 p. 15; table 10. (in Polish)

- ^ Magocsi 2010, p. 638-639.

- ^ Henryk Zieliński, Historia Polski 1914-1939, (1983) Wrocław: Ossolineum

- ^ "Główny Urząd Statystyczny Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej, drugi powszechny spis ludności z dn. 9.XII 1931 r. - Mieszkania i gospodarstwa domowe ludność" [Central Statistical Office of the Polish Republic, the second census dated 9.XII 1931 - Abodes and household populace] (PDF) (in Polish). Central Statistical office of the Polish Republic. 1938. p. 15. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 March 2014.

- ^ Magocsi 2015, p. 2-14.

- ^ a b Votruba, Martin (1998). "Linguisitic Minorities in Slovakia". In Christina Bratt Paulston; Donald Peckham (eds.). Linguistic Minorities in Central and Eastern Europe. Multilingual Matters. pp. 258–259. ISBN 1-85359-416-4. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ^ Friedhof und Katakomben im Stift St. Peter

- ^ Рыбалка 2020, p. 281-307.

- ^ Шелухин 1929, p. 20-27.

- ^ Magocsi 2010, p. 58-59.

- ^ Magocsi 2015, p. 50-51.

- ^ "Rusini. Zarys etnografii Rusi". rewasz.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- ^ Moser 2017–2018, p. 119-135.

- ^ "Encyclopedia of Rusyn history and culture | WorldCat.org". search.worldcat.org. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ^ "A Successor to the Ukrainian Sages". m.day.kyiv.ua. Retrieved 21 September 2023.

- ^ Хорея Козацька - Бенкет Духовний. Частина Друга, 2012, retrieved 21 September 2023

- ^ The Cambridge Companion to Modern Russian Culture (2012). The Cambridge Companion to Modern Russian Culture. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107002524.

- ^ Petro Doroshenko at the Encyclopedia of Ukraine

Sources

- Bunčić, Daniel (2015). "On the dialectal basis of the Ruthenian literary language" (PDF). Die Welt der Slaven. 60 (2): 276–289.

- Himka, John-Paul (1999). Religion and Nationality in Western Ukraine: The Greek Catholic Church and the Ruthenian National Movement in Galicia, 1870-1900. Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0-7735-1812-4.

- Juchnowski, Jerzy; Sielezin, Jan R.; Maj, Ewa (2018). The Image of "White" and "Red" Russia in the Polish Political Thought of the 19th and 20th Century. Berlin: Peter Lang. doi:10.3726/b14194. ISBN 978-3-631-75751-2. S2CID 158160059.

- Krajcar, Jan (1963). "A Report on the Ruthenians and their Errors, prepared for the Fifth Lateran Council". Orientalia Christiana Periodica. 29: 79–94.

- Litwin, Henryk (1987). "Catholicization among the Ruthenian Nobility and Assimilation Processes in the Ukraine during the Years 1569-1648" (PDF). Acta Poloniae Historica. 55: 57–83.

- Magocsi, Paul R. (1995). "The Rusyn Question". Political Thought: Ukrainian Journal of Political Science. 2–3: 221–231.

- Magocsi, Paul R.; Pop, Ivan I., eds. (2005) [2002]. Encyclopedia of Rusyn History and Culture (2. rev. ed.). Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Magocsi, Paul R. (2010) [1996]. A History of Ukraine: The Land and Its Peoples (2. rev. ed.). Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1-4426-1021-7.

- Magocsi, Paul R. (2011). "The Fourth Rus': A New Reality in a New Europe" (PDF). Journal of Ukrainian Studies. 35-36 (2010-2011): 167–177.

- Magocsi, Paul R. (2015). With Their Backs to the Mountains: A History of Carpathian Rus' and Carpatho-Rusyns. Budapest-New York: Central European University Press. ISBN 978-615-5053-46-7.

- Moser, Michael A. (2017–2018). "The Fate of the Ruthenian or Little Russian (Ukrainian) Language in Austrian Galicia (1772-1867)". Harvard Ukrainian Studies. 35 (2017-2018) (1/4): 87–104. JSTOR 44983536.

- Myl'nikov, Alexander (1999). The Picture of the Slavic World: The View from the Eastern Europe: Views of Ethnic Names and Ethnicity (XVIth–beginning of the XVIIIth century). St. Petersburg: Петербургское востоковедение. ISBN 5-85803-117-X.

- Nakonechny, Ye. УКРАДЕНЕ ІМ'Я чому русини стали українцями [Stolen Name: Why Ruthenians Became Ukrainians] (in Ukrainian). Stefanyk Science Library (National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine). Lviv, 2001.

- Рыбалка, Андрей А. (2020). "Сны аббата Килиана". Novogardia: Международный журнал по истории и исторической географии Средневековой Руси. 5 (1): 281–307.

- Slivka, John (1973). Correct nomenclature: Greek rite or Byzantine rite: Rusin or Ruthenian: Rusin or Slovak?. New York: Slivka.

- Slivka, John (1989) [1977]. Who are we? Nationality: Rusin, Russian, Ruthenian, Slovak? Ecclesiastical name: Greek Rite Catholic, Byzantine Rite Catholic? (2nd ed.). New York: Slivka.

- Shipman, Andrew J. (1912a). "Ruthenian Rite". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 13. New York: Robert Appleton Company. pp. 276–277.

- Shipman, Andrew J. (1912b). "Ruthenians". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 13. New York: Robert Appleton Company. pp. 277–279.

- Soloviev, Alexandre V. (1959). "Weiß-, Schwarz- und Rotreußen: Versuch einer historisch-politischen Analyse". Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas. 7 (1): 1–33. JSTOR 41041575.

- Шелухин, Сергій (1929). Звідкіля походить Русь: Теорія кельтського походження Київської Русі з Франції [Where did Rus’ come from: The theory of the Celtic origin of Kievan Rus’ from France] (PDF) (in Ukrainian). Prague-Strašnice [Прага Страшниці]: Slovanské odděleni knihtiskárny A. Fišera. (Transliterated author name: Serhiy Shelukhin; previously romanised: Serhiy (or Sergey) Cheloukine).

Further reading

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Himka, John-Paul. "Ruthenians". Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine.

- "The Carpathian Connection" Carpatho-Rusyn Heritage

![Ethnographic groups of Ruthenians, from "Rusini, zarys etnografii na Rusi" (1928)[39]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/85/Ruskie_grupy_etniczne.jpg/180px-Ruskie_grupy_etniczne.jpg)