Kievan Rus'

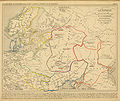

Kievan Rus',[a][b] also known as Kyivan Rus',[6][7] was the first East Slavic state and later an amalgam of principalities[8] in Eastern Europe from the late 9th to the mid-13th century.[9][10] Encompassing a variety of polities and peoples, including East Slavic, Norse,[11][12] and Finnic, it was ruled by the Rurik dynasty, founded by the Varangian prince Rurik.[13] The name was coined by Russian historians in the 19th century to describe the period when Kiev was at the center. At its greatest extent in the mid-11th century, Kievan Rus' stretched from the White Sea in the north to the Black Sea in the south and from the headwaters of the Vistula in the west to the Taman Peninsula in the east,[14][15] uniting the East Slavic tribes.[10]

According to the Primary Chronicle, the first ruler to unite East Slavic lands into what would become Kievan Rus' was Oleg the Wise (r. 879–912). He extended his control from Novgorod south along the Dnieper river valley to protect trade from Khazar incursions from the east,[10] and took control of the city. Sviatoslav I (r. 943–972) achieved the first major territorial expansion of the state, fighting a war of conquest against the Khazars. Vladimir the Great (r. 980–1015) spread Christianity with his own baptism and, by decree, extended it to all inhabitants of Kiev and beyond. Kievan Rus' reached its greatest extent under Yaroslav the Wise (r. 1019–1054); his sons assembled and issued its first written legal code, the Russkaya Pravda, shortly after his death.[2]

The state began to decline in the late 11th century, gradually disintegrating into various rival regional powers throughout the 12th century.[16] It was further weakened by external factors, such as the decline of the Byzantine Empire, its major economic partner, and the accompanying diminution of trade routes through its territory.[17] It finally fell to the Mongol invasion in the mid-13th century, though the Rurik dynasty would continue to rule until the death of Feodor I of Russia in 1598.[18] The modern nations of Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine all claim Kievan Rus' as their cultural ancestor,[c] with Belarus and Russia deriving their names from it, and the name Kievan Rus deriving itself from the city that is now the capital of Ukraine.[12][6]

Names

During its existence, Kievan Rus' was known as the "Rus' land" (Old East Slavic: ро́усьскаѧ землѧ́, romanized: rusĭskaę zemlę, from the ethnonym Роусь, Rusĭ; Medieval Greek: Ῥῶς, romanized: Rhos; Arabic: الروس, romanized: ar-Rūs), in Greek as Ῥωσία, Rhosia, in Old French as Russie, Rossie, in Latin as Rusia or Russia (with local German spelling variants Ruscia and Ruzzia), and from the 12th century also as Ruthenia or Rutenia.[20][21] Various etymologies have been proposed, including Ruotsi, the Finnish designation for Sweden or Ros, a tribe from the middle Dnieper valley region.[22]

According to the prevalent theory, the name Rus', like the Proto-Finnic name for Sweden (*rootsi), is derived from an Old Norse term for 'men who row' (rods-) because rowing was the main method of navigating the rivers of Eastern Europe, and could be linked to the Swedish coastal area of Roslagen (Rus-law) or Roden.[23][24] The name Rus' would then have the same origin as the Finnish and Estonian names for Sweden: Ruotsi and Rootsi.[24][25]

When the Varangian princes arrived, the name Rus' was associated with them and came to be associated with the territories they controlled. Initially the cities of Kiev, Chernigov, and Pereyaslavl and their surroundings came under Varangian control.[27][28]: 697 From the late tenth century, Vladimir the Great and Yaroslav the Wise tried to associate the name with all of the extended princely domains. Both meanings persisted in sources until the Mongol conquest: the narrower one, referring to the triangular territory east of the middle Dnieper, and the broader one, encompassing all the lands under the hegemony of Kiev's grand princes.[27][29]

The Russian term Kiyevskaya Rus' (Russian: Ки́евская Русь) was coined in the 19th century in Russian historiography to refer to the period when the centre was in Kiev.[30] In the 19th century it also appeared in Ukrainian as Kyivska Rus' (Ukrainian: Ки́ївська Русь).[31] Later, the Russian term was rendered into Belarusian as Kiyewskaya Rus' or Kijeŭskaja Ruś (Belarusian: Кіеўская Русь) and into Rusyn as Kyïvska Rus' (Rusyn: Київска Русь).[citation needed]

In English, the term was introduced in the early 20th century, when it was found in the 1913 English translation of Vasily Klyuchevsky's A History of Russia,[32] to distinguish the early polity from successor states, which were also named Rus'. The Varangian Rus' from Scandinavia used the Old Norse name Garðaríki, which, according to a common interpretation, means "land of towns".

History

Origin

Prior to the emergence of Kievan Rus' in the 9th century, most of the area north of the Black Sea was primarily populated by eastern Slavic tribes.[33] In the northern region around Novgorod were the Ilmen Slavs[34] and neighboring Krivichi, who occupied territories surrounding the headwaters of the West Dvina, Dnieper and Volga rivers. To their north, in the Ladoga and Karelia regions, were the Finnic Chud tribe. In the south, in the area around Kiev, were the Poliane,[35] the Drevliane to the west of the Dnieper, and the Severiane to the east. To their north and east were the Vyatichi, and to their south was forested land settled by Slav farmers, giving way to steppelands populated by nomadic herdsmen.[36]

There was once controversy over whether the Rus' were Varangians or Slavs (see anti-Normanism), however, more recently scholarly attention has focused more on debating how quickly an ancestrally Norse people assimilated into Slavic culture.[d] This uncertainty is due largely to a paucity of contemporary sources. Attempts to address this question instead rely on archaeological evidence, the accounts of foreign observers, and legends and literature from centuries later.[38] To some extent the controversy is related to the foundation myths of modern states in the region.[4] This often unfruitful debate over origins has periodically devolved into competing nationalist narratives of dubious scholarly value being promoted directly by various government bodies in a number of states. This was seen in the Stalinist period, when Soviet historiography sought to distance the Rus' from any connection to Germanic tribes, in an effort to dispel Nazi propaganda claiming the Russian state owed its existence and origins to the supposedly racially superior Norse tribes.[39] More recently, in the context of resurgent nationalism in post-Soviet states, Anglophone scholarship has analyzed renewed efforts to use this debate to create ethno-nationalist foundation stories, with governments sometimes directly involved in the project.[40] Conferences and publications questioning the Norse origins of the Rus' have been supported directly by state policy in some cases, and the resultant foundation myths have been included in some school textbooks in Russia.[41]

While Varangians were Norse traders and Vikings,[42] many Russian and Ukrainian nationalist historians argue that the Rus' were themselves Slavs.[43][44][45][46] Normanist theories focus on the earliest written source for the East Slavs, the Primary Chronicle, which was produced in the 12th century.[47] Nationalist accounts on the other hand have suggested that the Rus' were present before the arrival of the Varangians,[48] noting that only a handful of Scandinavian words can be found in Russian and that Scandinavian names in the early chronicles were soon replaced by Slavic names.[49]

Nevertheless, the close connection between the Rus' and the Norse is confirmed both by extensive Scandinavian settlement in Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine and by Slavic influences in the Swedish language.[50][51] Though the debate over the origin of the Rus' remains politically charged, there is broad agreement that if the proto-Rus' were indeed originally Norse, they were quickly nativized, adopting Slavic languages and other cultural practices. This position, roughly representing a scholarly consensus (at least outside of nationalist historiography), was summarized by the historian, F. Donald Logan, "in 839, the Rus were Swedes; in 1043 the Rus were Slavs".[37]

Ahmad ibn Fadlan, an Arab traveler during the 10th century, provided one of the earliest written descriptions of the Rus': "They are as tall as a date palm, blond and ruddy, so that they do not need to wear a tunic nor a cloak; rather the men among them wear garments that only cover half of his body and leaves one of his hands free."[52] Liutprand of Cremona, who was twice an envoy to the Byzantine court (949 and 968), identifies the "Russi" with the Norse ("the Russi, whom we call Norsemen by another name")[53] but explains the name as a Greek term referring to their physical traits ("A certain people made up of a part of the Norse, whom the Greeks call [...] the Russi on account of their physical features, we designate as Norsemen because of the location of their origin.").[54] Leo the Deacon, a 10th-century Byzantine historian and chronicler, refers to the Rus' as "Scythians" and notes that they tended to adopt Greek rituals and customs.[55]

Calling of the Varangians

According to the Primary Chronicle, the territories of the East Slavs in the 9th century were divided between the Varangians and the Khazars.[56] The Varangians are first mentioned imposing tribute from Slavic and Finnic tribes in 859.[57][non-primary source needed] In 862, various tribes rebelled against the Varangians, driving them "back beyond the sea and, refusing them further tribute, set out to govern themselves".[57]

They said to themselves, "Let us seek a prince who may rule over us, and judge us according to the Law." They accordingly went overseas to the Varangian Rus'. ... The Chuds, the Slavs, the Krivichs and the Ves then said to the Rus', "Our land is great and rich, but there is no order in it. Come to rule and reign over us". They thus selected three brothers with their kinfolk, who took with them all the Rus' and migrated.[58]

Modern scholars find this an unlikely series of events, probably made up by the 12th-century Orthodox priests who authored the Chronicle as an explanation how the Vikings managed to conquer the lands along the Varangian route so easily, as well as to support the legitimacy of the Rurikid dynasty.[59] The three brothers—Rurik, Sineus and Truvor—supposedly established themselves in Novgorod, Beloozero and Izborsk, respectively.[60] Two of the brothers died, and Rurik became the sole ruler of the territory and progenitor of the Rurik dynasty.[61] A short time later, two of Rurik's men, Askold and Dir, asked him for permission to go to Tsargrad (Constantinople). On their way south, they came upon "a small city on a hill", Kiev, which was a tributary of the Khazars at the time, stayed there and "established their dominion over the country of the Polyanians."[62][58][59]

The Primary Chronicle reports that Askold and Dir continued to Constantinople with a navy to attack the city in 863–66, catching the Byzantines by surprise and ravaging the surrounding area,[63][non-primary source needed] though other accounts date the attack in 860.[64][65] Patriarch Photius vividly describes the "universal" devastation of the suburbs and nearby islands,[66] and another account further details the destruction and slaughter of the invasion.[67] The Rus' turned back before attacking the city itself, due either to a storm dispersing their boats, the return of the Emperor, or in a later account, due to a miracle after a ceremonial appeal by the Patriarch and the Emperor to the Virgin.[64][65] The attack was the first encounter between the Rus' and Byzantines and led the Patriarch to send missionaries north to engage and attempt to convert the Rus' and the Slavs.[68][69]

Foundation of the Kievan state

Rurik led the Rus' until his death in about 879 or 882, bequeathing his kingdom to his kinsman, Prince Oleg, as regent for his young son, Igor.[70] According to the Primary Chronicle, in 880–82, Oleg led a military force south along the Dnieper river, capturing Smolensk and Lyubech before reaching Kiev, where he deposed and killed Askold and Dir: "Oleg set himself up as prince in Kiev, and declared that it should be the "mother of Rus' cities".[71][e] Oleg set about consolidating his power over the surrounding region and the riverways north to Novgorod, imposing tribute on the East Slav tribes.[62]

In 883, he conquered the Drevlians, imposing a fur tribute on them. By 885 he had subjugated the Poliane, Severiane, Vyatichi, and Radimichs, forbidding them to pay further tribute to the Khazars. Oleg continued to develop and expand a network of Rus' forts in Slavic lands, begun by Rurik in the north.[73]

The new Kievan state prospered due to its abundant supply of furs, beeswax, honey and slaves for export,[74] and because it controlled three main trade routes of Eastern Europe. In the north, Novgorod served as a commercial link between the Baltic Sea and the Volga trade route to the lands of the Volga Bulgars, the Khazars, and across the Caspian Sea as far as Baghdad, providing access to markets and products from Central Asia and the Middle East.[75][76] Trade from the Baltic also moved south on a network of rivers and short portages along the Dnieper known as the "route from the Varangians to the Greeks," continuing to the Black Sea and on to Constantinople.[77]

Kiev was a central outpost along the Dnieper route and a hub with the east–west overland trade route between the Khazars and the Germanic lands of Central Europe.[77] and may have been a staging post for Radhanite Jewish traders between Western Europe, Itil and China.[78] These commercial connections enriched Rus' merchants and princes, funding military forces and the construction of churches, palaces, fortifications, and further towns.[76] Demand for luxury goods fostered production of expensive jewelry and religious wares, allowing their export, and an advanced credit and money-lending system may have also been in place.[74]

Early foreign relations

Volatile steppe politics

The rapid expansion of the Rus' to the south led to conflict and volatile relationships with the Khazars and other neighbors on the Pontic steppe.[79][80] The Khazars dominated trade from the Volga-Don steppes to eastern Crimea and the northern Caucasus during the 8th century, an era historians call the 'Pax Khazarica',[81] trading and frequently allying with the Byzantine Empire against Persians and Arabs. In the late 8th century, the collapse of the Göktürk Khaganate led the Magyars and the Pechenegs to migrate west from Central Asia into the steppe region,[82] leading to military conflict, disruption of trade, and instability within the Khazar Khaganate.[83] The Rus' and Slavs had earlier allied with the Khazars against Arab raids on the Caucasus, but they increasingly worked against them to secure control of the trade routes.[84]

The Byzantine Empire was able to take advantage of the turmoil to expand its political influence and commercial relationships, first with the Khazars and later with the Rus' and other steppe groups.[85] The Byzantines established the Theme of Cherson, formally known as Klimata, in the Crimea in the 830s to defend against raids by the Rus' and to protect vital grain shipments supplying Constantinople.[65] Cherson also served as a key diplomatic link with the Khazars and others on the steppe, and it became the centre of Black Sea commerce.[86] The Byzantines also helped the Khazars build a fortress at Sarkel on the Don river to protect their northwest frontier against incursions by the Turkic migrants and the Rus', and to control caravan trade routes and the portage between the Don and Volga rivers.[87]

The expansion of the Rus' put further military and economic pressure on the Khazars, depriving them of territory, tributaries and trade.[88] In around 890, Oleg waged an indecisive war in the lands of the lower Dniester and Dnieper rivers with the Tivertsi and the Ulichs, who were likely acting as vassals of the Magyars, blocking Rus' access to the Black Sea.[89] In 894, the Magyars and Pechenegs were drawn into the wars between the Byzantines and the Bulgarian Empire. The Byzantines arranged for the Magyars to attack Bulgarian territory from the north, and Bulgaria in turn persuaded the Pechenegs to attack the Magyars from their rear.[90][91]

Boxed in, the Magyars were forced to migrate further west across the Carpathian Mountains into the Hungarian plain, depriving the Khazars of an important ally and a buffer from the Rus'.[90][91] The migration of the Magyars allowed access for the Rus' to the Black Sea,[92] and they soon launched excursions into Khazar territory along the sea coast, up the Don river, and into the lower Volga region. The Rus' were raiding and plundering into the Caspian Sea region from 864,[f] with the first large-scale expedition in 913, when they extensively raided Baku, Gilan, Mazandaran and penetrated into the Caucasus.[g][94][95][96]

As the 10th century progressed, the Khazars were no longer able to command tribute from the Volga Bulgars, and their relationship with the Byzantines deteriorated, as Byzantium increasingly allied with the Pechenegs against them.[97] The Pechenegs were thus secure to raid the lands of the Khazars from their base between the Volga and Don rivers, allowing them to expand to the west.[98] Relations between the Rus' and Pechenegs were complex, as the groups alternately formed alliances with and against one another. The Pechenegs were nomads roaming the steppe raising livestock which they traded with the Rus' for agricultural goods and other products.[99]

The lucrative Rus' trade with the Byzantine Empire had to pass through Pecheneg-controlled territory, so the need for generally peaceful relations was essential. Nevertheless, while the Primary Chronicle reports the Pechenegs entering Rus' territory in 915 and then making peace, they were waging war with one another again in 920.[100][101][non-primary source needed] Pechenegs are reported assisting the Rus' in later campaigns against the Byzantines, yet allied with the Byzantines against the Rus' at other times.[102]

Rus'–Byzantine relations

After the Rus' attack on Constantinople in 860, the Byzantine Patriarch Photius sent missionaries north to convert the Rus' and the Slavs to Christianity. Prince Rastislav of Moravia had requested the Emperor to provide teachers to interpret the holy scriptures, so in 863 the brothers Cyril and Methodius were sent as missionaries, due to their knowledge of the Slavonic language.[69][103][failed verification][104][non-primary source needed] The Slavs had no written language, so the brothers devised the Glagolitic alphabet, later replaced by Cyrillic (developed in the First Bulgarian Empire) and standardized the language of the Slavs, later known as Old Church Slavonic. They translated portions of the Bible and drafted the first Slavic civil code and other documents, and the language and texts spread throughout Slavic territories, including Kievan Rus'.[citation needed] The mission of Cyril and Methodius served both evangelical and diplomatic purposes, spreading Byzantine cultural influence in support of imperial foreign policy.[105][dead link] In 867 the Patriarch announced that the Rus' had accepted a bishop, and in 874 he speaks of an "Archbishop of the Rus'."[68]

Relations between the Rus' and Byzantines became more complex after Oleg took control over Kiev, reflecting commercial, cultural, and military concerns.[106] The wealth and income of the Rus' depended heavily upon trade with Byzantium. Constantine Porphyrogenitus described the annual course of the princes of Kiev, collecting tribute from client tribes, assembling the product into a flotilla of hundreds of boats, conducting them down the Dnieper to the Black Sea, and sailing to the estuary of the Dniester, the Danube delta, and on to Constantinople.[99][107] On their return trip they would carry silk fabrics, spices, wine, and fruit.[68][108]

The importance of this trade relationship led to military action when disputes arose. The Primary Chronicle reports that the Rus' attacked Constantinople again in 907, probably to secure trade access. The Chronicle glorifies the military prowess and shrewdness of Oleg, an account imbued with legendary detail.[68][108] Byzantine sources do not mention the attack, but a pair of treaties in 907 and 911 set forth a trade agreement with the Rus',[100][109] the terms suggesting pressure on the Byzantines, who granted the Rus' quarters and supplies for their merchants and tax-free trading privileges in Constantinople.[68][110]

The Chronicle provides a mythic tale of Oleg's death. A sorcerer prophesies that the death of the prince would be associated with a certain horse. Oleg has the horse sequestered, and it later dies. Oleg goes to visit the horse and stands over the carcass, gloating that he had outlived the threat, when a snake strikes him from among the bones, and he soon becomes ill and dies.[111][112][non-primary source needed] The Chronicle reports that Prince Igor succeeded Oleg in 913, and after some brief conflicts with the Drevlians and the Pechenegs, a period of peace ensued for over twenty years.[citation needed]

In 941, Igor led another major Rus' attack on Constantinople, probably over trading rights again.[68] A navy of 10,000 vessels, including Pecheneg allies, landed on the Bithynian coast and devastated the Asiatic shore of the Bosphorus.[113] The attack was well timed, perhaps due to intelligence, as the Byzantine fleet was occupied with the Arabs in the Mediterranean, and the bulk of its army was stationed in the east. The Rus' burned towns, churches and monasteries, butchering the people and amassing booty. The emperor arranged for a small group of retired ships to be outfitted with Greek fire throwers and sent them out to meet the Rus', luring them into surrounding the contingent before unleashing the Greek fire.[114]

Liutprand of Cremona wrote that "the Rus', seeing the flames, jumped overboard, preferring water to fire. Some sank, weighed down by the weight of their breastplates and helmets; others caught fire." Those captured were beheaded. The ploy dispelled the Rus' fleet, but their attacks continued into the hinterland as far as Nicomedia, with many atrocities reported as victims were crucified and set up for use as targets. At last a Byzantine army arrived from the Balkans to drive the Rus' back, and a naval contingent reportedly destroyed much of the Rus' fleet on its return voyage (possibly an exaggeration since the Rus' soon mounted another attack). The outcome indicates increased military might by Byzantium since 911, suggesting a shift in the balance of power.[113]

Igor returned to Kiev keen for revenge. He assembled a large force of warriors from among neighboring Slavs and Pecheneg allies, and sent for reinforcements of Varangians from "beyond the sea".[114][115] In 944, the Rus' force advanced again on the Greeks, by land and sea, and a Byzantine force from Cherson responded. The Emperor sent gifts and offered tribute in lieu of war, and the Rus' accepted. Envoys were sent between the Rus', the Byzantines, and the Bulgarians in 945, and a peace treaty was completed. The agreement again focused on trade, but this time with terms less favorable to the Rus', including stringent regulations on the conduct of Rus' merchants in Cherson and Constantinople and specific punishments for violations of the law.[116][non-primary source needed] The Byzantines may have been motivated to enter the treaty out of concern of a prolonged alliance of the Rus', Pechenegs, and Bulgarians against them,[117] though the more favorable terms further suggest a shift in power.[113]

Sviatoslav

Following the death of Igor in 945, his wife Olga ruled as regent in Kiev until their son Sviatoslav reached maturity (c. 963).[h] His decade-long reign over Kievan Rus' was marked by rapid expansion through the conquest of the Khazars of the Pontic steppe and the invasion of the Balkans. By the end of his short life, Sviatoslav carved out for himself the largest state in Europe, eventually moving his capital from Kiev to Pereyaslavets on the Danube in 969.[citation needed]

In contrast with his mother's conversion to Christianity, Sviatoslav, like his druzhina, remained a staunch pagan. Due to his abrupt death in an ambush in 972, Sviatoslav's conquests, for the most part, were not consolidated into a functioning empire, while his failure to establish a stable succession led to a fratricidal feud among his sons, which resulted in two of his three sons being killed.[citation needed]

Reign of Vladimir and Christianisation

It is not clearly documented when the title of grand prince was first introduced, but the importance of the Kiev principality was recognized after the death of Sviatoslav I in 972 and the ensuing struggle between Vladimir and Yaropolk. The region of Kiev dominated the region for the next two centuries. The grand prince (or grand duke) of Kiev controlled the lands around the city, and his formally subordinate relatives ruled the other cities and paid him tribute. The zenith of the state's power came during the reigns of Vladimir the Great (r. 980–1015) and Prince Yaroslav I the Wise (r. 1019–1054). Both rulers continued the steady expansion of Kievan Rus' that had begun under Oleg.[citation needed]

Vladimir had been prince of Novgorod when his father Sviatoslav I died in 972, but fled to Scandinavia in 977 after his half-brother Yaropolk killed his other half-brother Oleg.[119] According to the Primary Chronicle, Vladimir assembled a host of Varangian warriors, first subdued the Principality of Polotsk and then defeated and killed Yaropolk, thus establishing his reign over the entire Kievan Rus' realm.[119]

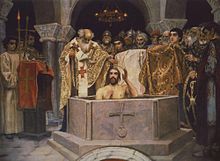

Although sometimes solely attributed to Vladimir, the Christianization of Kievan Rus' was a long and complicated process that began before the state's formation.[120] As early as the 1st century AD, Greeks in the Black Sea Colonies converted to Christianity, and the Primary Chronicle even records the legend of Andrew the Apostle's mission to these coastal settlements, as well as blessing the site of present-day Kyiv.[120] The Goths migrated to through the region in the 3rd century, adopting Arian Christianity in the 4th century, leaving behind 4th- and 5th-century churches excavated in Crimea, although the Hunnic invasion of the 370s halted Christianisation for several centuries.[120] Some of the earliest Kievan princes and princesses such as Askold and Dir and Olga of Kiev reportedly converted to Christianity, but Oleg, Igor and Sviatoslav remained pagans.[121]

The Primary Chronicle records the legend that when Vladimir had decided to accept a new faith instead of traditional Slavic paganism, he sent out some of his most valued advisors and warriors as emissaries to different parts of Europe. They visited the Christians of the Latin Church, the Jews, and the Muslims before finally arriving in Constantinople. They rejected Islam because, among other things, it prohibited the consumption of alcohol, and Judaism because the god of the Jews had permitted his chosen people to be deprived of their country.[122] They found the ceremonies in the Roman church to be dull. But at Constantinople, they were so astounded by the beauty of the cathedral of Hagia Sophia and the liturgical service held there that they made up their minds there and then about the faith they would like to follow. Upon their arrival home, they convinced Vladimir that the faith of the Byzantine Rite was the best choice of all, upon which Vladimir made a journey to Constantinople and arranged to marry Princess Anna, the sister of Byzantine emperor Basil II.[122] Historically, it is more likely that he adopted Byzantine Christianity in order to strengthen his diplomatic relations with Constantinople.[123] Vladimir's choice of Eastern Christianity may have reflected his close personal ties with Constantinople, which dominated the Black Sea and hence trade on Kiev's most vital commercial route, the Dnieper River.[124] According to the Primary Chronicle, Vladimir was baptised in c. 987, and ordered the population of Kiev to be baptised in August 988.[123] The greatest resistance against Christianisation appears to have occurred in northern towns including Novgorod, Suzdal, and Belozersk.[123]

Adherence to the Eastern Church had long-range political, cultural, and religious consequences.[124] The church had a liturgy written in Cyrillic and a corpus of translations from Greek that had been produced for the Slavic peoples. This literature facilitated the conversion to Christianity of the Eastern Slavs and introduced them to rudimentary Greek philosophy, science, and historiography without the necessity of learning Greek (there were some merchants who did business with Greeks and likely had an understanding of contemporary business Greek).[124] Following the Great Schism of 1054, the Kievan church maintained communion with both Rome and Constantinople for some time, but along with most of the Eastern churches it eventually split to follow the Eastern Orthodox. That being said, unlike other parts of the Greek world, Kievan Rus' did not have a strong hostility to the Western world.[125]

Reign of Yaroslav

Yaroslav, known as "the Wise", struggled for power with his brothers. A son of Vladimir the Great, he was prince of Novgorod at the time of his father's death in 1015.[126]

Although he first established his rule over Kiev in 1019, he did not have uncontested rule of all of Kievan Rus' until 1036. Like Vladimir, Yaroslav was eager to improve relations with the rest of Europe, especially the Byzantine Empire. Yaroslav's granddaughter, Eupraxia, the daughter of his son Vsevolod I, was married to Henry IV, Holy Roman Emperor. Yaroslav also arranged marriages for his sister and three daughters to the kings of Poland, France, Hungary and Norway.[citation needed]

Yaroslav promulgated the first law code of Kievan Rus', the Russkaya Pravda; built Saint Sophia Cathedral in Kiev and Saint Sophia Cathedral in Novgorod; patronized local clergy and monasticism; and is said to have founded a school system. Yaroslav's sons developed the great Kiev Pechersk Lavra (monastery).[citation needed]

Succession issues

In the centuries that followed the state's foundation, Rurik's descendants shared power over Kievan Rus'. The means by which royal power was transferred from one Rurikid ruler to the next is unclear, however, historian Paul Magocsi mentioned that 'Scholars have debated what the actual system of succession was or whether there was any system at all.'[127] According to historian Nancy Kollmann, the rota system was used with the princely succession moving from elder to younger brother and from uncle to nephew, as well as from father to son. Junior members of the dynasty usually began their official careers as rulers of a minor district, progressed to more lucrative principalities, and then competed for the coveted throne of Kiev.[128] Whatever the case, according to professor Ivan Katchanovski 'no adequate system of succession to the Kievan throne was developed' after the death of Yaroslav the Wise (r. 1019–1054), commencing a process of gradual disintegration.[129]

The unconventional power succession system fomented constant hatred and rivalry within the royal family. Familicide was frequently deployed to obtain power and can be traced particularly during the time of the Yaroslavichi (sons of Yaroslav), when the established succession system was skipped in the establishment of Vladimir II Monomakh as the Grand Prince of Kiev (r. 1113–1125), in turn creating major squabbles between the Olegovichi (sons of Oleg I) from Chernigov, the Monomakhovichi from Pereyaslavl, the Izyaslavichi (sons of Iziaslav) from Turov–Volhynia, and the Polotsk Princes. The position of the grand prince of Kiev was weakened by the growing influence of regional clans.[citation needed]

Fragmentation and decline

The rival Principality of Polotsk was contesting the power of the Grand Prince by occupying Novgorod, while Rostislav Vladimirovich was fighting for the Black Sea port of Tmutarakan belonging to Chernigov. Three of Yaroslav's sons that first allied together found themselves fighting each other especially after their defeat to the Cuman forces in 1068 at the Battle of the Alta River.[citation needed]

The ruling Grand Prince Iziaslav fled to Poland asking for support and in a couple of years returned to establish the order. The affairs became even more complicated by the end of the 11th century driving the state into chaos and constant warfare. On the initiative of Vladimir II Monomakh in 1097 the Council of Liubech of Kievan Rus' took place near Chernigov with the main intention to find an understanding among the fighting sides.[citation needed]

By 1130, all descendants of Vseslav the Seer had been exiled to the Byzantine Empire by Mstislav the Great. The most fierce resistance to the Monomakhs was posed by the Olegovichi when the izgoi Vsevolod II managed to become the Grand Prince of Kiev. The Rostislavichi, who had initially established in the lands of Galicia by 1189, were defeated by the Monomakh-Piast descendant Roman the Great.[citation needed]

The decline of Constantinople—a main trading partner of Kievan Rus'—played a significant role in the decline of the Kievan Rus'. The trade route from the Varangians to the Greeks, along which the goods were moving from the Black Sea (mainly Byzantine) through eastern Europe to the Baltic, was a cornerstone of Kievan wealth and prosperity. These trading routes became less important as the Byzantine Empire declined in power and Western Europe created new trade routes to Asia and the Near East. As people relied less on passing through the territories of Kievan Rus' for trade, the economy of Kievan Rus' suffered.[130]

The last ruler to maintain a united state was Mstislav the Great. After his death in 1132, Kievan Rus' fell into recession and a rapid decline, and Mstislav's successor Yaropolk II of Kiev, instead of focusing on the external threat of the Cumans, was embroiled in conflicts with the growing power of the Novgorod Republic. In March 1169, a coalition of native princes led by Andrei Bogolyubsky of Vladimir sacked Kiev.[131] This changed the perception of Kiev and was evidence of the fragmentation of the Kievan Rus'.[132] By the end of the 12th century, the Kievan state fragmented even further, into roughly twelve different principalities.[133]

The Crusades brought a shift in European trade routes that accelerated the decline of Kievan Rus'. In 1204, the forces of the Fourth Crusade sacked Constantinople, making the Dnieper trade route marginal.[17] At the same time, the Livonian Brothers of the Sword (of the Northern Crusades) were conquering the Baltic region and threatening the Lands of Novgorod.[citation needed]

In the north, the Novgorod Republic prospered because it controlled trade routes from the River Volga to the Baltic Sea. As Kievan Rus' declined, Novgorod became more independent. A local oligarchy ruled Novgorod; major government decisions were made by a town assembly, which also elected a prince as the city's military leader. In 1136, Novgorod revolted against Kiev, and became independent.[134] Now an independent city republic, and referred to as "Lord Novgorod the Great" it would spread its "mercantile interest" to the west and the north; to the Baltic Sea and the low-populated forest regions, respectively.[134]

In 1199, Prince Roman Mstislavych united the two previously separate principalities of Galicia and Volhynia.[135] His son Daniel (r. 1238–1264) looked for support from the West.[136] He accepted a crown from the Roman papacy.[136]

Final disintegration

Following the Mongol invasion of Cumania (or the Kipchaks), in which case many Cuman rulers fled to Rus', such as Köten, the state finally disintegrated under the pressure of the Mongol invasion of Kievan Rus', fragmenting it into successor principalities who paid tribute to the Golden Horde (the so-called Tatar Yoke). Just prior to the Mongol invasion, Kievan Rus' had been a relatively prosperous region. International trade as well as skilled artisans flourished, while its farms produced enough to feed the urban population. After the invasion of the late 1230s, the economy shattered, and its population were either slaughtered or sold into slavery; while skilled laborers and artisans were sent to the Mongol's steppe regions.[137]

On the southwestern periphery, Kievan Rus' was succeeded by the Principality of Galicia-Volhynia. Later, as these territories, now part of modern central Ukraine and Belarus, fell to the Gediminids, the powerful, largely Ruthenized Grand Duchy of Lithuania drew heavily on the cultural and legal traditions of the Rus'. From 1398 until the Union of Lublin in 1569, its full name was the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Ruthenia and Samogitia.[138]

On the north-eastern periphery of Kievan Rus', traditions were adapted in the Vladimir-Suzdal principality that gradually gravitated towards Moscow. To the very north, the Novgorod and Pskov feudal republics were less autocratic than Vladimir-Suzdal-Moscow until they were absorbed by the Grand Duchy of Moscow. Modern historians from Belarus, Russia and Ukraine alike consider Kievan Rus' the first period of their modern countries' histories.[129][19]

Society

Culture

The lands of Kievan Rus' were mostly made up of forests and steppes (see East European forest steppe and Central European mixed forests), while its main rivers all originated in the Valdai Hills: the Dnieper, and primarily populated by Slavic and Finnic tribes.[139] All tribes were hunter-gatherers to a certain degree, but the Slavs were primarily agriculturalists, growing cereal grains and crops, as well as raising livestock.[38] Before the emergence of the Kievan state, these tribes had their own leaders and gods, and interaction between tribes was occasionally marked either by trading goods or fighting battles.[38] The most valuable commodities traded were captive slaves and fur pelts (usually in exchange for silver coins or oriental finery), and common trade partners were Volga Bolghar, Khazar Itil and Byzantine Chersonesus.[38] By the early 9th century, bands of Scandinavian adventurers known as Varangians and later Rus' started plundering various (Slavic) villages in the region, later extracting tribute in exchange for protection against pillaging by other Varangians.[38] Over time, these relationships of tribute for protection evolved into more permanent political structures: the Rus' lords became princes and the Slavic populace their subjects.[140]

Economy

In the early 10th century, Kievan Rus' mainly traded with other tribes in Eastern Europe and Scandinavia. "There was little need for complex social structures to carry out these exchanges in the forests north of the steppes. So long as the entrepreneurs operated in small numbers and kept to the north, they did not catch the attention of observers or writers". The Rus' also had strong trading ties to Byzantium, particularly in the early 900s, as treaties in 911 and 944 indicate. These treaties deal with the treatment of runaway Byzantine slaves and limitations on the amounts of certain commodities such as silk that could be bought from Byzantium. The Rus' used log rafts floated down the Dnieper River by Slavic tribes for the transport of goods, particularly slaves to Byzantium.[141]

During the Kievan era, trade and transport depended largely on networks of rivers and portages.[142] By this period, trade networks had expanded to cater to more than just local demand. This is evidenced by a survey of glassware found in over 30 sites ranging from Suzdal, Drutsk and Belozeroo, which found that a substantial majority was manufactured in Kiev. Kiev was the main depot and transit point for trade between itself, Byzantium and the Black Sea region. Even though this trade network had already been existent, the volume of which had expanded rapidly in the 11th century. Kiev was also dominant in internal trade between the towns of Rus'; it held a monopoly on glassware products (glass vessels, glazed pottery and window glass) up until the early- to mid-12th century until which it lost its monopoly to the other towns in Rus'. Inlaid enamel production techniques was borrowed from Byzantine. Byzantine amphorae, wine and olive oil have been found along the middle Dnieper, suggesting trade between Kiev, along trade towns to Byzantium.[143]

In winter, the ruler of Kiev went out on rounds, visiting Dregovichs, Krivichs, Drevlians, Severians, and other subordinated tribes. Some paid tribute in money, some in furs or other commodities, and some in slaves. This system was called poliudie.[144][145]

Religion

According to Martin (2009), 'Christianity, Judaism, and Islam had long been known in these lands, and Olga personally converted to Christianity. When Vladimir assumed the throne, however, he set idols of Norse, Slav, Finn, and Iranian gods, worshipped by the disparate elements of his society, on a hilltop in Kiev in an attempt to create a single pantheon for his people. But for reasons that remain unclear he soon abandoned this attempt in favour of Christianity.'[146]

Architecture

The architecture of Kievan Rus' is the earliest period of Russian, Ukrainian and Belarusian architecture, using the foundations of Byzantine culture, but with great use of innovations and architectural features. Most remains are Russian Orthodox churches or parts of the gates and fortifications of cities.[citation needed]

Administrative divisions

The East Slavic lands were originally divided into princely domains called zemlias, "lands", or volosts (from a term meaning "power" or "government").[147] A smaller clan-sized unit was called a verv, or pogost, headed by a kopa or viche.[148]

From the 11th to 13th centuries the principalities were divided into volosts, its centre usually called a pryhorod (or Gord a fortified settlement).[149][147] A volost consisted of several vervs or hromadas (commune or community).[147] A local official was called a volostel or starosta.[147]

Yaroslav the Wise assigned priority to the major principalities to reduce familial conflict over succession.[127]

- Principality of Kiev and Novgorod, for the eldest son Iziaslav I of Kiev, who became grand prince.

- Principality of Chernigov and Tmutarakan, for Sviatoslav II of Kiev

- Principality of Pereyaslavl and Rostov-Suzdal, for Vsevolod I of Kiev

- Principality of Smolensk, for Vyacheslav Yaroslavich

- Principality of Volhynia, for Igor Yaroslavich

Not mentioned by Yaroslav were Principality of Polotsk, ruled by Yaroslav's older brother Iziaslav of Polotsk that was to remain under the control of his descendants, and the Principality of Galicia, eventually taken by the dynasty of his grandson Rostyslav.[127]

Foreign relations

Military history

Steppe peoples

From the 9th century on, the Pecheneg nomads had an uneasy relationship with Kievan Rus'. For over two centuries they launched sporadic raids into Rus', which sometimes escalated into full-scale wars, such as the 920 war on the Pechenegs by Igor of Kiev, reported in the Primary Chronicle, but there were also temporary military alliances e.g., the 943 Byzantine campaign by Igor.[i] In 968, the Pechenegs attacked and besieged the city of Kiev.[150]

Boniak was a Cuman khan who led a series of invasions on Kievan Rus'. In 1096, Boniak attacked Kiev, plundered the Kiev Monastery of the Caves, and burned down the prince's palace in Berestovo. He was defeated in 1107 by Vladimir Monomakh, Oleg, Sviatopolk and other princes of Rus'.[151]

Byzantine Empire

Byzantium quickly became the main trading and cultural partner for Kiev, but relations were not always friendly. One of the largest military accomplishments of the Rurikid dynasty was the attack on Byzantium in 960. Pilgrims of the Rus' had been making the journey from Kiev to Constantinople for many years, and Constantine Porphyrogenitus, the Emperor of the Byzantine Empire, believed that this gave them significant information about the arduous parts of the journey and where travelers were most at risk, as would be pertinent for an invasion. This route took travelers through domain of the Pechenegs, journeying mostly by river. In June 941, the Rus' staged a naval ambush on Byzantine forces, making up for their smaller numbers with small, maneuverable boats. These boats were ill-equipped for the transportation of large quantities of treasure, suggesting that looting was not the goal. The raid was led, according to the Primary Chronicle, by a king called Igor. Three years later, the treaty of 944 stated that all ships approaching Byzantium must be preceded by a letter from the Rurikid prince stating the number of ships and assuring their peaceful intent. This not only indicates fear of another surprise attack, but an increased Kievan presence in the Black Sea.[152]

Mongols

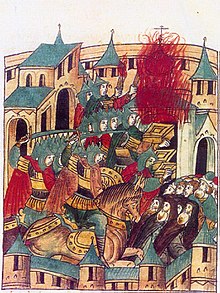

The Mongol Empire invaded Kievan Rus' in the 13th century, devastating numerous cities, including Ryazan, Kolomna, Moscow, Vladimir and Kiev. The siege of Kiev in 1240 by the Mongols is generally understood as the end of Kievan Rus'. Batu Khan went on to subjugate Galicia and Volhynia, raid Poland and Hungary, and founded the Golden Horde at Sarai in 1242.[153] The conquests mostly halted due to a succession crisis following khan Ogedei's death, leading Batu to return to Mongolia to select the clan's next overlord.[153]

Historical assessment

Kievan Rus', although sparsely populated compared to Western Europe,[154] was not only the largest contemporary European state in terms of area but also culturally advanced.[155] Literacy in Kiev, Novgorod and other large cities was high.[156][j] Novgorod had a sewage system and wood pavement not often found in other cities at the time.[158] The Russkaya Pravda confined punishments to fines and generally did not use capital punishment.[k] Certain rights were accorded to women, such as property and inheritance rights.[160][161][162]

The economic development of Kievan Rus' may be reflected in its demographics. Scholarly estimates of Kiev's population around 1200 range from 36,000 to 50,000 (at the time, Paris had about 50,000, and London 30,000).[163] Novgorod had about 10,000 to 15,000 inhabitants in 1000, and about double that number by 1200, while Chernigov had a larger land area than both Kiev and Novgorod at the time, and is therefore estimated have had even more inhabitants.[163] Constantinople, then one of the largest cities in the world, had a population of about 400,000 around 1180.[164] Soviet scholar Mikhail Tikhomirov calculated that Kievan Rus' had around 300 urban centres on the eve of the Mongol invasion.[165]

Kievan Rus' also played an important genealogical role in European politics. Yaroslav the Wise, whose stepmother belonged to the Macedonian dynasty that ruled the Byzantine Empire from 867 to 1056, married the only legitimate daughter of the king who Christianized Sweden. His daughters became queens of Hungary, France and Norway; his sons married the daughters of a Polish king and Byzantine emperor, and a niece of the Pope; and his granddaughters were a German empress and (according to one theory) the queen of Scotland. A grandson married the only daughter of the last Anglo-Saxon king of England. Thus the Rurikids were a well-connected royal family of the time.[l][m]

Serhii Plokhy (2006) proposed to "denationalize" Kievan Rus': contrary to what modern nationalist interpretations had been doing, he argued for 'separating Kievan Rus' as a multi-ethnic state from the national histories of Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus. This applies to the word Rus' and to the concept of the Rus' Land.'[168] According to Halperin (2010), 'Plokhy's approach does not invalidate analysis of rival claims by Muscovy, Lithuania or Ukraine to the Kievan inheritance; it merely relegates such pretensions entirely to the realm of ideology.'[169]

In popular culture

- Finnish folk metal band Turisas has produced various songs on its albums The Varangian Way (2007) and Stand Up and Fight (2011) which feature Scandinavian names (Jarisleif in "In the Court of Jarisleif" for Grand Prince Yaroslav) and Old Norse exonyms for toponyms (such as Holmgard in "To Holmgard and Beyond" for Veliky Novgorod, and Miklagard in "Miklagard Overture" for Constantinople) connected to Kievan Rus'. According to Bosselmann (2018) and DiGioia (2020), Scandinavian names are used by Turisas 'as a way to convey the historical context of the songs' subject matter', namely 'the stories of the Scandinavian pre-Christian populations and their travels eastwards along the way known as the Way of the Varangians to the Greek to Constantinople'.[170][171]

Gallery

Collection of maps

- Map of 8th- to 9th-century Rus' by Leonard Chodzko (1861)

- Map of 9th-century Rus' by Antoine Philippe Houze (1844)

- Map of 9th-century Rus' by F. S. Weller (1893)

- Map of Rus' in Europe in 1000 (1911)

- Map of Rus' in 1097 (1911)

- Map of 1139 by Joachim Lelewel; northeast is identified as "trans-forest colonies" (Zalesie)

- Fragment of the 1154 Tabula Rogeriana by Muhammad al-Idrisi

- Overview of principalities of Kievan Rus'

Art and architecture

- Ship burial of a Rus' chieftain as described by the Arab traveler Ahmad ibn Fadlan, who visited north-eastern Europe in the 10th century.

Henryk Siemiradzki (1883) - Model of the original Saint Sophia Cathedral, Kyiv; used on modern 2 hryvni of Ukraine

- The Nativity, a Kievan (possibly Galician) illumination from the Gertrude Psalter

- Rider armor and horse equipment. Iron, 12th–13th centuries, S. Lipovets, Kiev province, mound 264, military burial. State Hermitage Museum.

See also

- De Administrando Imperio – 10th-century Byzantine source written by emperor Constantine VII

- History of Belarus

- History of Russia

- History of Ukraine

- Rus' chronicle – genre of Old East Slavic literature

- Slavic studies

- European Russia

References

Explanatory notes

- ^ "The Rise of Kievan Rus'"[4]

- ^ "In these early centuries East Slavic tribes and their neighbours coalesced into the Christian state of Kievan Rus."[5]

- ^ 'For all the salient differences between these three post-Soviet nations, they have much in common when it comes to their culture and history, which goes back to Kievan Rus', the medieval East Slavic state based in the capital of present-day Ukraine,'[19]

- ^ "The controversies over the nature of the Rus and the origins of the Russian state have bedevilled Viking studies, and indeed Russian history, for well over a century. It is historically certain that the Rus were Swedes. The evidence is incontrovertible, and that a debate still lingers at some levels of historical writing is clear evidence of the holding power of received notions. The debate over this issue – futile, embittered, tendentious, doctrinaire – served to obscure the most serious and genuine historical problem which remains: the assimilation of these Viking Rus into the Slavic people among whom they lived. The principal historical question is not whether the Rus were Scandinavians or Slavs, but, rather, how quickly these Scandinavian Rus became absorbed into Slavic life and culture."[37]

- ^ Normanist scholars accept this moment as the foundation of the Kievan Rus' state, while anti-Normanists point to other Chronicle entries to argue that the East Slav Polianes were already in the process of forming a state independently.[72]

- ^ Abaskun, first recorded by Ptolemy as Socanaa, was documented in Arab sources as "the most famous port of the Khazarian Sea". It was situated within three days' journey from Gorgan. The southern part of the Caspian Sea was known as the "Sea of Abaskun".[93]

- ^ The Khazar khagan initially granted the Rus' safe passage in exchange for a share of the booty but attacked them on their return voyage, killing most of the raiders and seizing their haul.

- ^ If Olga was indeed born in 879, as the Primary Chronicle seems to imply, she would have been about 65 at the time of Sviatoslav's birth. There are clearly some problems with chronology.[118]

- ^ Ibn Haukal describes the Pechenegs as long-standing allies of the Rus' people, whom they invariably accompanied during the 10th-century Caspian expeditions.[citation needed]

- ^ "It is to the credit of Vladimir and his advisors they built not only churches but schools as well. This compulsory baptism was followed by compulsory education... Schools were thus founded not only in Kiev but also in provincial cities. From the "Life of St. Feodosi" we know that a school existed in Kursk around the year of 1023. By the time of Yaroslav's reign (1019–54), education had struck roots and its benefits were apparent. Around 1030, Iaroslav founded a divinity school in Novgorod for 300 children of both laymen and clergy to be instructed in "book-learning". As a general measure, he made the parish priests "teach the people"."[157]

- ^ "The most notable aspect of the criminal provisions was that punishments took the form of seizure of property, banishment, or, more often, payment of a fine. Even murder and other severe crimes (arson, organised horse thieving, and robbery) were settled by monetary fines. Although the death penalty had been introduced by Vladimir the Great, it too was soon replaced by fines."[159]

- ^ "In medieval Europe, a mark of a dynasty's prestige and power was the willingness with which other leading dynasties entered into matrimonial relations with it. Measured by this standard, Yaroslav's prestige must have been great indeed... . Little wonder that Iaroslav is often dubbed by historians as 'the father-in-law of Europe.'"[166]

- ^ "By means of these marital ties, Kievan Rus' became well known throughout Europe."[167]

Citations

- ^ Slavic Culture in the Middle Ages. California Slavic Studies. University of California Press. 2021. p. 141. ISBN 9780520309180.

- ^ a b Bushkovitch 2011, p. 11.

- ^ Б.Ц.Урланис. Рост населения в Европе (PDF) (in Russian). p. 89. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ^ a b Magocsi 2010, p. 55.

- ^ Martin 2009b, p. 1.

- ^ a b Rubin, Barnett R.; Snyder, Jack L. (1998). Post-Soviet Political Order: Conflict and State Building. London: Routledge. p. 93.

As the capital of Kyivan Rus ...

. "The Golden Age of Kyivan Rus'". gis.huri.harvard.edu. Archived from the original on 30 October 2022. Retrieved 30 October 2022. "Ukraine – History, section "Kyivan (Kievan) Rus"". Encyclopedia Britannica. 5 March 2020. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 2 July 2020.- Zhdan, Mykhailo (1988). "Kyivan Rus'". Encyclopedia of Ukraine. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- ^ Katchanovski et al. 2013, p. 196.

- ^ Martin 2009b, p. 1–5.

- ^ Curtis, Glenn Eldon (1998). Russia: A Country Study. Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. ISBN 978-0-8444-0866-8.

Kievan Rus', the first East Slavic state, emerged in the ninth century A.D. and developed a complex and frequently unstable political system that flourished until the thirteenth century, when it declined abruptly.

- ^ a b c John Channon & Robert Hudson, Penguin Historical Atlas of Russia (Penguin, 1995), p.14–16.

- ^ "Rus | people | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Archived from the original on 24 March 2022. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- ^ a b Little, Becky (4 December 2019). "When Viking Kings and Queens Ruled Medieval Russia". HISTORY. Archived from the original on 6 April 2022. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- ^ Kievan Rus Archived 18 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ^ Kyivan Rus' Archived 26 March 2023 at the Wayback Machine, Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 2 (1988), Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies.

- ^ See Historical map of Kievan Rus' from 980 to 1054 Archived 11 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Paul Robert Magocsi, Historical Atlas of East Central Europe (1993), p.15.

- ^ a b "Civilization in Eastern Europe Byzantium and Orthodox Europe". occawlonline.pearsoned.com. 2000. Archived from the original on 22 January 2010.

- ^ Picková, Dana, O počátcích státu Rusů, in: Historický obzor 18, 2007, č.11/12, s. 253–261

- ^ a b Plokhy 2006, p. 10–15.

- ^ (in Russian) Назаренко А. В. Глава I Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine // Древняя Русь на международных путях: Междисциплинарные очерки культурных, торговых, политических связей IX—XII вв. Archived 31 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine — М.: Языки русской культуры, 2001. — c. 40, 42—45, 49—50. — ISBN 5-7859-0085-8.

- ^ Magocsi 2010, p. 72–73.

- ^ Magocsi 2010, p. 56–57.

- ^ Blöndal, Sigfús (1978). The Varangians of Byzantium. Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-521-03552-1. Archived from the original on 14 April 2023. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ^ a b Stefan Brink, 'Who were the Vikings?', in The Viking World Archived 14 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine, ed. by Stefan Brink and Neil Price (Abingdon: Routledge, 2008), pp. 4–10 (pp. 6–7).

- ^ "Russ, adj. and n." OED Online, Oxford University Press, June 2018, www.oed.com/view/Entry/169069. Accessed 12 January 2021.

- ^ Motsia, Oleksandr (2009). «Руська» термінологія в Київському та Галицько-Волинському літописних зводах ["Ruthenian" question in Kyiv and Halych-Volyn annalistic codes] (PDF). Arkheolohiia (1). doi:10.6084/M9.FIGSHARE.1492467.V1. ISSN 0235-3490. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ^ a b Magocsi 2010, p. 72.

- ^ Melnikova, E. A.; Petrukhin, V. Ya.; Institute of World History of the Russian Academy of Sciences, eds. (2014). Древняя Русь в средневековом мире: энциклопедия [Early Rus in the medieval world: encyclopedia]. Moscow: Ladomir. OCLC 1077080265.

- ^ Флоря, Борис Николаевич (1993). "Исторические судьбы Руси и этническое самосознание восточных славян в XII—XV веках" (PDF). Славяноведение (in Russian). 2: 12-15. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- ^ Tolochko, A. P. (1999). "Khimera "Kievskoy Rusi"". Rodina (in Russian) (8): 29–33.

- ^ Колесса, Олександер Михайлович (1898). Столїтє обновленої українсько-руської лїтератури: (1798–1898). Львів: З друкарні Наукового Товариства імені Шевченка під зарядом К. Беднарського. p. 26.

В XII та XIII в., в часі, коли південна, Київська Русь породила такі перли літературні ... (In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, at a time when southern, Kyivan Rus' gave birth to such literary pearls ...)

- ^ Vasily Klyuchevsky, A History of Russia, vol. 3, pp. 98, 104

- ^ Martin 2004, p. 2–4.

- ^ Carl Waldman & Catherine Mason, Encyclopedia of European Peoples (2006) Archived 22 March 2023 at the Wayback Machine, p.415.

- ^ Freeze, Gregory L. (2009). Russia: A History. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-19-956041-7.

- Chadwick, Nora K. (2013). The Beginnings of Russian History: An Enquiry Into Sources. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-107-65256-9.

- ^ Martin 2004, p. 4.

- ^ a b Logan 2005, p. 184.

- ^ a b c d e Martin 2009b, p. 2.

- ^ Elena Melnikova, 'The "Varangian Problem": Science in the Grip of Ideology and Politics', in Russia's Identity in International Relations: Images, Perceptions, Misperceptions, ed. by Ray Taras (Abingdon: Routledge, 2013), pp. 42–52.

- ^ Jonathan Shepard, "Review Article: Back in Old Rus and the USSR: Archaeology, History and Politics", English Historical Review, vol. 131 (no. 549) (2016), 384–405 doi:10.1093/ehr/cew104 (p. 387), citing Leo S. Klejn, Soviet Archaeology: Trends, Schools, and History, trans. by Rosh Ireland and Kevin Windle (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), p. 119.

- ^ Artem Istranin and Alexander Drono, "Competing historical Narratives in Russian Textbooks", in Mutual Images: Textbook Representations of Historical Neighbours in the East of Europe, ed. by János M. Bak and Robert Maier, Eckert. Dossiers, 10 ([Braunschweig]: Georg Eckert Institute for International Textbook Research, 2017), 31–43 (pp. 35–36).

- ^ "Kievan Rus". World History Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- Nikolay Karamzin (1818). History of the Russian State. Stuttgart: Steiner. Archived from the original on 27 October 2020. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- Sergey Solovyov (1851). History of Russia from the Earliest Times. Stuttgart: Steiner. Archived from the original on 11 May 2021. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ Smith, Graham (10 September 1998). Nation-building in the Post-Soviet Borderlands: The Politics of National Identities. Cambridge University Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-521-59968-9.

The Ukrainophile claim is that, in the words of the 1991 declaration of Ukrainian independence, the Ukrainians have a 'thousand-year tradition of state-building'... As in Russophile historiography, the 'Normanist theory' that Rus' was in fact established by Viking envoys, is rejected as a German invention.

- ^ Magocsi 2010, p. 56.

- ^ Nicholas V. Riasanovsky, A History of Russia, pp. 23–28 (Oxford Press, 1984).

- ^ Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine Archived 7 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine Normanist theory

- ^ Riasanovsky, p. 25.

- ^ Riasanovsky, pp. 25–27.

- ^ David R. Stone, A Military History of Russia: From Ivan the Terrible to the war in Chechnya (2006), pp. 2–3.

- ^ Williams, Tom (28 February 2014). "Vikings in Russia". blog.britishmuseum.org. The British Museum. Archived from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

Objects now on loan to the British Museum for the BP exhibition Vikings: life and legend indicate the extent of Scandinavian settlement from the Baltic to the Black Sea . . .

- ^ Franklin, Simon; Shepard, Jonathan (1996). The Emergence of Rus: 750–1200. Longman History of Russia. Essex: Harlow. ISBN 0-582-49090-1.

- ^ Fadlan, Ibn (2005). (Richard Frey) Ibn Fadlan's Journey to Russia. Princeton, NJ: Markus Wiener Publishers.

- ^ Rusios, quos alio nos nomine Nordmannos apellamus. (in Polish) Henryk Paszkiewicz (2000). Wzrost potęgi Moskwy, s.13, Kraków. ISBN 83-86956-93-3

- ^ Gens quaedam est sub aquilonis parte constituta, quam a qualitate corporis Graeci vocant [...] Rusios, nos vero a positione loci nominamus Nordmannos. James Lea Cate. Medieval and Historiographical Essays in Honor of James Westfall Thompson. p.482. The University of Chicago Press, 1938

- ^ Leo the Deacon, The History of Leo the Deacon: Byzantine Military Expansion in the Tenth Century (Alice-Mary Talbot & Denis Sullivan, eds., 2005), pp. 193–94 Archived 22 March 2023 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Magocsi 2010, p. 59.

- ^ a b Cross & Sherbowitz-Wetzor 1930, p. 6.

- ^ a b Cross & Sherbowitz-Wetzor 1953, p. 7.

- ^ a b Konstam, Angus (2005). Historical Atlas of the Viking World. London: Mercury Books London. p. 165. ISBN 1904668127.

This unlikely invitation was clearly a vehicle to explain the annexation of these territories by the Vikings, and to lend authority to a later generation of Rus rulers.

- ^ Magocsi 2010, p. 55, 59–60.

- ^ Thomas McCray, Russia and the Former Soviet Republics (2006), p. 26

- ^ a b Martin 2009a, p. 37.

- ^ Cross & Sherbowitz-Wetzor 1953, p. 8.

- ^ a b Ostrogorsky 1969, p. 228.

- ^ a b c Majeska 2009, p. 51.

- ^ Logan 2005, p. 172–73.

- ^ The Life of St. George of Amastris describes the Rus' as a barbaric people "who are brutal and crude and bear no remnant of love for humankind". David Jenkins, The Life of St. George of Amastris Archived 5 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine (University of Notre Dame Press, 2001), p.18.

- ^ a b c d e f Majeska 2009, p. 52.

- ^ a b Dimitri Obolensky, Byzantium and the Slavs (1994), p.245 Archived 22 March 2023 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Martin 2009b, p. 3.

- ^ Cross & Sherbowitz-Wetzor 1953, p. 7–8.

- ^ Martin 2009a, p. 37–40.

- ^ Vernadsky 1973, p. 23.

- ^ a b Walter Moss, A History of Russia: To 1917 (2005), p. 37 Archived 22 March 2023 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Magocsi 2010, p. 96.

- ^ a b Martin 2009a, p. 47.

- ^ a b Martin 2009a, p. 40, 47.

- ^ Perrie, Maureen; Lieven, D. C. B.; Suny, Ronald Grigor (2006). The Cambridge History of Russia: Volume 1, From Early Rus' to 1689. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-81227-6. Archived from the original on 22 March 2023. Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- ^ Magocsi 2010, p. 62, 66.

- ^ Martin 2004, p. 16–19.

- ^ Victor Spinei, The Romanians and the Turkic Nomads North of the Danube Delta from the Tenth to the Mid-Thirteenth Century (2009), pp. 47–49 Archived 22 March 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Peter B. Golden, Central Asia in World History (2011), p. 63 Archived 22 March 2023 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Magocsi 2010, p. 62–63.

- ^ Vernadsky 1973, p. 20.

- ^ Magocsi 2010, p. 62.

- ^ Angeliki Papageorgiou, "Theme of Cherson (Klimata)" Archived 29 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Encyclopaedia of the Hellenic World (Foundation of the Hellenic World, 2008).

- ^ Kevin Alan Brook, The Jews of Khazaria (2006), pp. 31–32 Archived 22 March 2023 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Martin 2004, p. 15–16.

- ^ Vernadsky 1973, p. 62.

- ^ a b John V. A. Fine, The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century (1991), pp. 138–139 Archived 22 March 2023 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b Spanei (2009), pp. 66, 70.

- ^ Vernadsky 1973, p. 28.

- ^ B. N. Zakhoder (1898–1960). The Caspian Compilation of Records about Eastern Europe (online version Archived 1 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine) (in Russian).

- ^ Vernadsky 1973, p. 32–33.

- ^ Gunilla Larsson. Ship and society: maritime ideology in Late Iron Age Sweden Archived 23 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine Uppsala Universitet, Department of Archaeology and Ancient History, 2007. ISBN 91-506-1915-2. p. 208.

- ^ Cahiers du monde russe et soviétique, Volume 35, Number 4 Archived 22 March 2023 at the Wayback Machine. Mouton, 1994. (originally from the University of California, digitalised on 9 March 2010)

- ^ Moss (2005), p. 29 Archived 22 March 2023 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Magocsi 2010, p. 66.

- ^ a b Martin 2004, p. 17.

- ^ a b Magocsi 2010, p. 67.

- ^ Cross & Sherbowitz-Wetzor 1930, p. 71.

- ^ Moss (2005), pp.29–30 Archived 22 March 2023 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Saints Cyril and Methodius, [1] Archived 5 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Cross & Sherbowitz-Wetzor 1930, p. 62–63.

- ^ Obolensky (1994), pp..244–246 Archived 22 March 2023 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Magocsi 2010, p. 66–67.

- ^ Vernadsky 1973, p. 28–31.

- ^ a b Vernadsky 1973, p. 22.

- ^ John Lind, Varangians in Europe's Eastern and Northern Periphery, Ennen & nyt (2004:4).

- ^ Logan 2005, p. 192.

- ^ Vernadsky 1973, p. 22–23.

- ^ Cross & Sherbowitz-Wetzor 1930, p. 69.

- ^ a b c Ostrogorsky 1969, p. 277.

- ^ a b Logan 2005, p. 193.

- ^ Cross & Sherbowitz-Wetzor 1930, p. 72.

- ^ Cross & Sherbowitz-Wetzor 1930, p. 73–78.

- ^ Spinei, p.93.

- ^ Ostrowski 2018, p. 41–42.

- ^ a b Martin 2007, pp. 1–2.

- ^ a b c Katchanovski et al. 2013, p. 74.

- ^ Katchanovski et al. 2013, p. 74–75.

- ^ a b Martin 2004, p. 6–7.

- ^ a b c Katchanovski et al. 2013, p. 75.

- ^ a b c Franklin, Simon (1992). "Greek in Kievan Rus'". Dumbarton Oaks Papers. 46: 69–81. doi:10.2307/1291640. JSTOR 1291640.

- ^ Colucci, Michele (1989). "The Image of Western Christianity in the Culture of Kievan Rus'". Harvard Ukrainian Studies. 12/13: 576–586.

- ^ "Yaroslav I (prince of Kiev) – Encyclopædia Britannica". Britannica.com. 22 May 2014. Archived from the original on 17 October 2014. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ a b c Magocsi 2010, p. 82.

- ^ Nancy Shields Kollmann, "Collateral Succession in Kievan Rus'." Harvard Ukrainian Studies 14 (1990): 377–87.

- ^ a b Katchanovski et al. 2013, p. 1.

- ^ Thompson, John M. (John Means) (25 July 2017). Russia : a historical introduction from Kievan Rus' to the present. Ward, Christopher J., 1972– (Eighth ed.). New York, NY. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-8133-4985-5. OCLC 987591571.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Franklin, Simon; Shepard, Jonathan (1996), The Emergence of Russia 750–1200, Routledge, pp. 323–4, ISBN 978-1-317-87224-5, archived from the original on 23 April 2023, retrieved 14 November 2020

- ^ Pelenski, Jaroslaw (1987). "The Sack of Kiev of 1169: Its Significance for the Succession to Kievan Rus'". Harvard Ukrainian Studies. 11: 303–316.

- ^ Kollmann, Nancy (1990). "Collateral Succession in Kievan Rus". Harvard Ukrainian Studies. 14: 377–387.

- ^ a b Magocsi 2010, p. 85.

- ^ Magocsi 2010, p. 124.

- ^ a b Magocsi 2010, p. 126.

- ^ Halperin, Charles J. (1985). Russia and the Golden Horde : the Mongol Impact on Medieval Russian History. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 75–77. ISBN 978-0-253-35033-6.

- ^ "Русина О.В. ВЕЛИКЕ КНЯЗІВСТВО ЛИТОВСЬКЕ // Енциклопедія історії України: Т. 1: А-В / Редкол.: В. А. Смолій (голова) та ін. НАН України. Інститут історії України. – К.: В-во "Наукова думка", 2003. – 688 с.: іл". Archived from the original on 21 April 2016. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- ^ Martin 2009b, p. 1–2.

- ^ Martin 2009b, p. 2, 5.

- ^ Franklin, Simon, and Jonathan Shepard (1996). The Emergence of Rus 750–1200. Harlow, Essex: Longman Group, Ltd., pp. 27–28, 127.

- ^ William H. McNeill (1 January 1979). Jean Cuisenier (ed.). Europe as a Cultural Area. World Anthropology. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 32–33. ISBN 978-3-11-080070-8. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

For a while, it looked as if the Scandinavian thrust toward monarchy and centralization might succeed in building two impressive and imperial structures: a Danish empire of the northern seas, and a Varangian empire of the Russian rivers, headquartered at Kiev.... In the east, new hordes of steppe nomads, fresh from central Asia, intruded upon the river-based empire of the Varangians by taking over its southern portion.

- ^ Simon, Frank (1996). The Emergence of Rus, 750–1200. Longman. p. 281. ISBN 978-0-582-49091-8.

- ^ Martin 2004, p. 12–13.

- ^ История Европы с древнейших времен до наших дней. Т. 2. М.: Наука, 1988. ISBN 978-5-02-009036-1. С. 201.

- ^ Martin 2009b, p. 6.

- ^ a b c d Zhukovsky, Arkadii (1993). "Volost". Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine. Archived from the original on 5 December 2022. Retrieved 24 January 2023.

- ^ "Verv". Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine. Archived from the original on 1 January 2023. Retrieved 24 January 2023.

- ^ Katchanovski et al. 2013, p. 11.

- ^ Lowe, Steven; Ryaboy, Dmitriy V. The Pechenegs, History and Warfare.

- ^ Боняк [Boniak]. Great Soviet Encyclopedia (in Russian). 1969–1978. Archived from the original on 6 July 2013. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- ^ Franklin, Simon, and Jonathan Shepard (1996). The Emergence of Rus 750–1200. Harlow, Essex: Longman Group, Ltd. pp. 112–119

- ^ a b Martin 2007, p. 155.

- ^ "Medieval Sourcebook: Tables on Population in Medieval Europe". Fordham University. Archived from the original on 10 January 2010. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ Sherman, Charles Phineas (1917). "Russia". Roman Law in the Modern World. Boston: The Boston Book Company. p. 191. Archived from the original on 23 April 2023. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

The adoption of Christianity by Vladimir... was followed by commerce with the Byzantine Empire. In its wake came Byzantine art and culture. And in the course of the next century, what is now Southeastern Russia became more advanced in civilization than any western European State of the period, for Russia came in for a share of Byzantine culture, then vastly superior to the rudeness of Western nations.

- ^ Tikhomirov, Mikhail Nikolaevich (1956). "Literacy among the citi dwellers". Drevnerusskie goroda (Cities of Ancient Rus) (in Russian). Moscow. p. 261. Archived from the original on 25 April 2010. Retrieved 18 March 2006.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Vernadsky 1973, p. 277.

- ^ Miklashevsky, N.; et al. (2000). "Istoriya vodoprovoda v Rossii". ИСТОРИЯ ВОДОПРОВОДА В РОССИИ [History of water-supply in Russia] (in Russian). Saint Petersburg, Russia: ?. p. 240. ISBN 978-5-8206-0114-9. Archived from the original on 10 March 2006. Retrieved 18 March 2006.

- ^ Magocsi 2010, p. 95.

- ^ Tikhomirov, Mikhail Nikolaevich (1953). Пособие для изучения Русской Правды (in Russian) (2nd ed.). Moscow: Издание Московского университета. p. 190. Archived from the original on 14 June 2006. Retrieved 18 March 2006.

- ^ Martin 2004, p. 72.

- ^ Vernadsky 1973, p. 154.

- ^ a b Martin 2004, p. 61.

- ^ J. Phillips, The Fourth Crusade and the Sack of Constantinople page 144

- ^ Tikhomirov, Mikhail Nikolaevich (1956). "The origin of Russian cities". Drevnerusskie goroda (Cities of Ancient Rus) (in Russian). Moscow. pp. 36, 39, 43. Archived from the original on 25 April 2010. Retrieved 18 March 2006.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Subtelny, Orest (1988). Ukraine: A History. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 35. ISBN 0-8020-5808-6.)

- ^ Magocsi 2010, p. 81.

- ^ Halperin 2010, p. 2.

- ^ Halperin 2010, p. 3.

- ^ DiGioia, Amanda (2020). Multilingual Metal Music: Sociocultural, Linguistic and Literary Perspectives on Heavy Metal Lyrics. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing. p. 85. ISBN 9781839099489. Archived from the original on 27 January 2023. Retrieved 27 January 2023.

- ^ Velasco Laguna, Manuel (2012). Breve historia de los vikingos (versión extendida) (in Spanish). Madrid: Nowtilus. p. 168. ISBN 9788499673479. Archived from the original on 27 January 2023. Retrieved 27 January 2023.

Primary sources

- Cross, Samuel Hazzard; Sherbowitz-Wetzor, Olgerd P. (1930). The Russian Primary Chronicle, Laurentian Text. Translated and edited by Samuel Hazzard Cross and Olgerd P. Sherbowitz-Wetzor (1930) (PDF). Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Mediaeval Academy of America. p. 325. Retrieved 26 January 2023.

- Cross, Samuel Hazzard; Sherbowitz-Wetzor, Olgerd P. (2013) [1953]. SLA 218. Ukrainian Literature and Culture. Excerpts from The Rus' Primary Chronicle (Povest vremennykh let, PVL) (PDF). Toronto: Electronic Library of Ukrainian Literature, University of Toronto. p. 16. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 May 2014. Retrieved 26 January 2023.

Secondary sources

- Bushkovitch, Paul (2011). A Concise History of Russia. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 491. ISBN 9781139504447. Archived from the original on 23 April 2023. Retrieved 26 January 2023.

- Gleason, Abbott (2009). A Companion to Russian History. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. p. 566. ISBN 9781444308426. Retrieved 26 January 2023.

- Martin, Janet (2009a). "Chapter Three: The First East Slavic State". A Companion to Russian History. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 34–50. ISBN 9781444308426. Retrieved 26 January 2023.

- Majeska, George (2009). "Chapter Four: Rus' and the Byzantine Empire". A Companion to Russian History. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 51–65. ISBN 9781444308426. Retrieved 26 January 2023.

- Katchanovski, Ivan; Kohut, Zenon E.; Nesebio, Bohdan Y.; Yurkevich, Myroslav (2013). Historical Dictionary of Ukraine. Lanham, Maryland; Toronto; Plymouth: Scarecrow Press. p. 992. ISBN 9780810878471. Archived from the original on 23 April 2023. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- Logan, F. Donald (2005). The Vikings in History. New York: Routledge (Taylor & Francis). p. 205. ISBN 9780415327565. Archived from the original on 23 April 2023. Retrieved 26 January 2023. (third edition)

- Magocsi, Paul R. (2010). A History of Ukraine: The Land and Its Peoples. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 896. ISBN 978-1-4426-1021-7. Archived from the original on 23 April 2023. Retrieved 26 January 2023.

- Martin, Janet (1993). Medieval Russia: 980–1584. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521368324. (original). Later editions cited in this article:

- Martin, Janet (1995). Medieval Russia: 980–1584. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521362768. (first published)

- Martin, Janet (2004). Medieval Russia: 980–1584. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521368322. Archived from the original on 23 April 2023. Retrieved 11 October 2015. (digital printing 2004)

- Martin, Janet (2007). Medieval Russia: 980–1584. Second Edition. E-book. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-511-36800-4.

- Martin, Janet (2009b). "From Kiev to Muscovy: The Beginnings to 1450". In Freeze, Gregory (ed.). Russia: A History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 1–30. ISBN 978-0-19-150121-0. Archived from the original on 27 January 2023. Retrieved 27 January 2023. (third edition)

- Ostrogorsky, George (1969). History of the Byzantine State. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press. p. 760. Retrieved 26 January 2023.

- Plokhy, Serhii (2006). The Origins of the Slavic Nations: Premodern Identities in Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus (PDF). New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 10–15. ISBN 978-0-521-86403-9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- Halperin, Charles J. (2010). "Review Article. "National Identity in Premodern Rus'"". Russian History (Brill journal). 37 (3). Brill Publishers: 275–294. doi:10.1163/187633110X510446. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 2 February 2023.

- Ostrowski, Donald (2018). "Was There a Riurikid Dynasty in Early Rus'?". Canadian-American Slavic Studies. 52 (1): 30–49. doi:10.1163/22102396-05201009.

- Vernadsky, George (1973). "Russian Civilization in the Kievan Period: Education". Kievan Russia. Yale University Press. p. 412. ISBN 0-300-01647-6.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Country Studies. Federal Research Division. – Russia Archived 11 July 2012 at archive.today