Rozafa Castle

| Rozafa Castle Shkodra Castle | |

|---|---|

Kalaja e Rozafës Kalaja e Shkodrës | |

| Shkodër, Northwestern Albania | |

Rozafa Castle | |

| Coordinates | 42°02′47″N 19°29′37″E / 42.0465°N 19.4935°E |

| Site information | |

| Owner | |

| Controlled by | Illyrian tribes (Labeates, Ardiaei) Illyrian kingdom Duklja First Bulgarian Empire Serbian Grand Principality Great Powers |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Site history | |

| Built | 4th or early 3rd century BC (earliest detected walls)[1] |

| Materials | Limestone, brick |

Rozafa Castle (Albanian: Kalaja e Rozafës) or Shkodër Castle (Albanian: Kalaja e Shkodrës) is a castle near the city of Shkodër, in northwestern Albania. It rises imposingly on a rocky hill, 130 metres (430 ft) above sea level, surrounded by the Buna and Drin rivers. Shkodër is the seat of Shkodër County, and is one of Albania's oldest and most historic towns, as well as an important cultural and economic centre.

The hill was settled since the Early Bronze Age. The earliest fortification walls are dated to the 4th-3rd century BCE constituting the citadel of the Illyrian city of Skodra, which together with various sites of the lower city, shows the growing and vibrant nature of the Illyrian capital under the Labeatae, especially during the reign of king Gentius.[2][1] Nevertheless, the visible walls of the castle are mostly of Venetian construction.

Name

Although there have been several legends about the etymology of the name Rozafa, scholars have linked it with Resafa, the place where Saint Sergius died. Shkodra and the surrounding area have a long and well-documented tradition of venerating Sergius (Albanian: Shirgji).[3]

The castle is also named after the city of Shkodër (definite Albanian form: Shkodra).

History

Antiquity

Due to its strategic location, the hill had a prominent role in antiquity. There was an Illyrian stronghold during the rule of the Labeates and Ardiaei, whose capital was Scodra.[4]

During the Third Illyrian War the Illyrian king Gentius concentrated his forces in Scodra. When he was attacked by the Roman army led by L. Anicius Gallus, Gentius fled into the city and was trapped there hoping that his brother Caravantius would come at any moment with a large relieving army, but that did not happen. After his defeat, Gentius sent two prominent tribal leaders, Teuticus and Bellus, as envoys to negotiate with the Roman commander.[5] On the third day of the truce, Gentius surrendered to the Romans, was placed in custody and sent to Rome. The Roman army marched north of Scutari Lake where, at Meteon, they captured Gentius' wife queen Etuta, his brother Caravantius, his sons Scerdilaidas and Pleuratus along with leading Illyrians.[6]

The fall of the Illyrian kingdom in 168 BC[7] is transmitted by Livy in a ceremonial manner of the triumph of Anicius in Rome:

In a few days, both on land and sea did he defeat the brave Illyrian tribe, who had relied on their knowledge of their own territory and fortifications.

Medieval and Ottoman period

Within the castle there are the ruins of a 13th-century Venetian Catholic church, considered by scholars as the St. Stephen's Cathedral, which after the siege of Shkodër in the 15th century, when the Ottoman Empire captured the city, was transformed into the Fatih Sultan Mehmet Mosque.[8]

The castle has been the site of several famous sieges, including the siege of Shkodër of 1478-79 and the siege of Shkodër of 1912-13. The castle and its surroundings form an Archaeological Park of Albania.

Legend

A famous widespread legend about human sacrifice and immurement with the aim of building a facility is traditionally orally transmitted by Albanians and connected with the construction of the Rozafa Castle.[10][11][12][9][13][14][15] The existence of this Albanian legend is attested as early as 1505, in the work De obsidione Scodrensi, by the Albanian humanist and historian Marin Barleti.[16]

The story tells about the initiative of three brothers who set down to build a castle. They worked all day, but the foundation walls fell down at night. They met a wise old man who seems to know the solution of the problem asking them if they were married. When the three brothers responded positively, the old man said:[10]

If you really want to finish the castle, you must swear never to tell your wives what I am going to tell you now. The wife who brings you your food tomorrow you must bury alive in the wall of the castle. Only then will the foundations stay put and last forever.

The three brothers swore on besa to not speak with their wives of that happened. However the two eldest brothers broke their promise and quietly told their wives everything, while the honest youngest brother kept his besa and said nothing. The mother of the three brothers knew nothing of their agreement, and while the next afternoon at lunch time, she asked her daughters-in-law to bring lunch to the workers, two of them refused with an excuse. The brothers waited anxiously to see which wife was carrying the basket of food. It was Rozafa, the wife of the youngest brother, who left her younger son at home. Embittered, the youngest brother explained to her what the deal was, that she was to be sacrificed and buried in the wall of the castle so that they could finish building it, and she didn't protest but, worried about her infant son, she accepted being immured and made a request:[10]

I have but one request to make. When you wall me in, leave a hole for my right eye, for my right hand, for my right foot and for my right breast. I have a small son. When he starts to cry, I will cheer him up with my right eye, I will comfort him with my right hand, I will put him to sleep with my right foot and wean him with my right breast. Let my breast turn to stone and the castle flourish. May my son become a great hero, ruler of the world.

A well known version of the legend is the Serbian epic poem called The Building of Skadar (Зидање Скадра, Zidanje Skadra) published by Vuk Karadžić in 1815, after he recorded a folk song sung by a Herzegovinian storyteller named Old Rashko.[17][18][19] The three brothers in the legend were represented by members of the noble Mrnjavčević family, Vukašin, Uglješa and Gojko.[20] Furthermore, Dundes states that the name Gojko is invented.[21] Folklorist Alan Dundes notes that the ballad continued to be admired by generations of folksingers and ballad scholars.[22]

The cult of the maternal breasts and the motif of immurement that appear in the Albanian legend of Rozafa are reflections of the worship of the earth mother goddess in Albanian folk beliefs.[23] The local people believe that Rozafa's milk still flows in the walls of the stronghold she sacrificed herself to preserve. This is manifested by the native milkweeds flow when their stalks are broken, and limestone stalactites found within the original Illyrian gateway. Limestone deposits are scraped off by local women, and by mixing them with water they obtain a medicine to drink or apply to their breasts in order to increase their milk supply, and so that they can infuse their babies with the character and patriotism of Rozafa, the legendary immured woman.[9][11][12]

Tourism

| Period | Visitors |

| 2016 | 38,631[24] |

| 2017 | About 50,000[24] |

Gallery

- Central part of the castle

- Inside the castle

- Hall inside the castle

- A section of the wall overgrown by grass

- Rozafa castle in 1863

- View of the Buna river from the castle walls

- Ruins of the castle

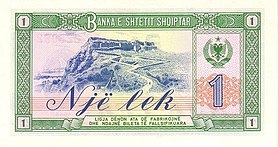

- View of the castle on the reverse of a 1964 1 Lek banknote

See also

References

- ^ a b Dyczek 2022: "A section of the original so-called Cyclopean walls has been traced and dated to the 4th (?) or early 3rd century BC (Figure 5). There is also some modest evidence of the Lower City walls seen by Livy. Considered in relation to the results of the excavations, this gives a provisional picture of the Hellenistic fortifications, as well as an improved understanding of the urban grid. The small finds: fragments of amphorae and amphora stoppers, and sherds of table ware come mainly from the 2nd century BC (Figure 6). Extensive geophysical (Figure 7) and archaeological research in the upcoming seasons of fieldwork will be instrumental in planning the gradual uncovering of the Hellenistic history of the town."

- ^ Galaty & Bejko 2023, p. 60: "Recently, excavations were reopened at Shkodër Castle by Shpuza, working in collaboration with Polish archaeologist Piotr Dyczek (recently summarized in Dyczek and Shpuza 2020). They began in 2011 with mapping, reconnaissance, and a survey of the inscriptions in the Venetian cistern (Shpuza and Dyczek 2012). They also excavated additional segments of the Iower town's fortification wall—originally excavated by Hoxha and Lahi (see above; apparently built in 340 AD, Dyczek and Shpuza 2014:393)—a round tower, an ossuary, and an Ottoman road and cemetery (fourteenth to fifteenth century AD) near the Xhamia e Plumbit (the Lead Mosque) (Dyczek and Shpuza 2014:393). Finds recovered from various test excavations date to the period of Gentius and demonstrate the presence of a vibrant, growing, pre- Roman (i.e., Illyrian) city (Shpuza and Dyczek 2012:444-445). In subsequent years, Dyczek and Shpuza (2014; see also Shpuza and Dyczek 2013, 2018) excavated 1 7 test trenches covering 400 sq. m., both inside and outside the fortress. Pottery and walls from the Hellenistic period (third to first century BC) were discovered both inside and outside the city walls, providing further support for the idea that the Illyrian city encompassed a Wide area, both atop the citadel and near the banks of the Drin and Buna rivers" [...] p. 65: "For example, despite identifying eighteen Illyrian settlements in the Shkodër region, and despite conducting large-scale excavations at six ot them, including massive, recent excavations at Shkodër Castle, we still possess only the foggiest of impressoins regarding how the regional Illyrian tribes formed and were organized."

- ^ Juka, Gëzim (2012). Shteti shqiptar dhe Shkodra: (1912 - 2012). Shtëpia Botuese "Rozafa". p. 6.

- ^ Evans 2006, p. 83.

- ^ Berranger 2007.

- ^ Wilkes 1995, p. 174.

- ^ Wilkes 1995, p. 72.

- ^ Kiel 1990, p. 230.

- ^ a b c Hosaflook 2012, pp. 261–262.

- ^ a b c Elsie 1994, p. 32.

- ^ a b Poghirc 1987, p. 179.

- ^ a b Tirta 2004, p. 191.

- ^ Dundes 1996, pp. 65, 68.

- ^ Cornis-Pope & Neubauer 2004, p. 269.

- ^ Fischer 2002, p. 6.

- ^ Kuka 1984, p. 163.

- ^ Dundes 1996, pp. 3, 146.

- ^ Cornis-Pope & Neubauer 2004, p. 273.

- ^ Skëndi 2007, p. 75.

- ^ Dundes 1996, p. 150.

- ^ Dundes 1996, p. 11.

- ^ Dundes 1996, p. 3.

- ^ Poghirc 1987, pp. 178–179; Tirta 2004, pp. 188–190.

- ^ a b "DRKK Shkodër". www.facebook.com. Retrieved 2018-06-12.

Sources

- Dyczek, Piotr (2022). "Scodra rediscovered". In Sonia Antonelli; Vasco La Salvia; Maria Cristina Mancini; Oliva Menozzi; Marco Moderato; Maria Carla Somma (eds.). Archaeologiae Una storia al plural: Studi in memoria di Sara Santoro. Archaeopress Publishing Ltd. pp. 219–228. ISBN 9781803272979.

- Galaty, Michael L.; Bejko, Lorenc (2023). "History of Archaeological Research in the Shkodër Region". In Galaty, Michael L.; Bejko, Lorenc (eds.). Archaeological Investigations in a Northern Albanian Province: Results of the Projekti Arkeologjik i Shkodrës (PASH): Volume One: Survey and Excavation Results. Memoirs Series. Vol. 64. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 9781951538736.

- Hosaflook, David (2012). "Appendix Four". In Hosaflook, David (ed.). The Siege of Shkodra: Albania's Courageous Stand Against Ottoman Conquest, 1478. Translated by David Hosaflook. Onufri Publishing House. ISBN 978-99956-87-77-9.

- Fischer, Bernd j. (2002). Albanian identities: myth and history. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34189-1. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- Kuka, Benjamin (1984). Questions of the Albanian Folklore. 8 Nëntori.

- Wilkes, J. J. (1995). The Illyrians. Oxford, United Kingdom: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-19807-5.

- Kiel, Machiel (1990). Research Centre for Islamic History, Art and Culture (ed.). Ottoman architecture in Albania (1385-1912) (in German). Vol. Band 5. Istanbul. ISBN 92-9063-330-1.

{{cite book}}:|periodical=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Berranger, Danièle (2007). Épire, Illyrie, Macédoine: mélanges offerts au professeur Pierre Cabanes. Presses Univ Blaise Pascal. ISBN 978-2845163515.

- Evans, Arthur; et al. (J. J. Wilkes) (2006). Ancient Illyria: An Archaeological Exploration. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 1845111672.

- Elsie, Robert (1994). Albanian Folktales and Legends. Naim Frashëri Publishing Company. Archived from the original (pdf) on 2009-07-28.

- Dundes, Alan (1996). The Walled-Up Wife: A Casebook. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 9780299150730.

- Cornis-Pope, Marcel; Neubauer, John (2004). History of the Literary Cultures of East-Central Europe: Junctures and Disjunctures in the 19th and 20th Centuries. John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 978-90-272-3455-1.

- Poghirc, Cicerone (1987). "Albanian Religion". In Mircea Eliade (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Religion. Vol. 1. New York: MacMillan Publishing Co. pp. 178–180.

- Skëndi, Stavro (2007). Poezia epike gojore e shqiptarëve dhe e sllavëve të jugut. Instituti i Dialogut & Komunikimit. ISBN 9789994398201.

- Tirta, Mark (2004). Petrit Bezhani (ed.). Mitologjia ndër shqiptarë (in Albanian). Tirana: Mësonjëtorja. ISBN 99927-938-9-9.