Rosary Sonatas

| Rosary Sonatas | |

|---|---|

| Violin sonatas by H. I. F. Biber | |

Violin with strings prepared for Sonata No. 11 | |

| Other name |

|

| Composed | around 1676 |

| Published | 1905 |

| Movements |

|

| Scoring |

|

The Rosary Sonatas (Rosenkranzsonaten, also known as the Mystery Sonatas or Copper-Engraving Sonatas) by Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber are a collection of 15 short sonatas for violin and continuo, with a final passacaglia for solo violin. Instead of a title, each sonatas has a copper-engraved vignette related to the Christian Rosary practice, and possibly to the Feast of the Guardian Angels.

It is presumed that the Mystery Sonatas were completed around 1676, but they were unknown until their publication in 1905. While Biber lost much popularity after his death, his music was never entirely forgotten due to the high technical skill required to play many of his works; this is especially true of his violin works. Once rediscovered, the Mystery Sonatas became one of Biber's most widely known composition. The work is prized for its virtuosic vocal style, scordatura tunings, and its programmatic structure.

History and discovery

Biber wrote a large body of instrumental music and is most famous for his violin sonatas, but he also wrote a large amount of sacred vocal music, of which many works were polychoral, with a notable example being his Missa Salisburgensis.

In his sonatas for violin, Biber integrated new technical skills with new compositional expression and was himself able to accomplish techniques that few violinists could at his time.[1] The Mystery Sonatas include very rapid passages, demanding double stops and an extended range, reaching positions on the violin that musicians had not yet been able to play.[2]

The original manuscript is stored in the Bavarian State Library in Munich. There is no title page, and the manuscript begins with a dedication to his employer, Prince-Archbishop Max Gandolph von Kuenburg. Because of the missing title page, it is uncertain what Biber intended the formal title of the piece to be and which instruments he intended for the accompaniment.[3][4] Although scholars assume that the sonatas were probably written around the year 1676, there is evidence that they were not all written at the same time or in the same context. This means that Biber could have collected the sonatas from his previously composed works to form a collection and replaced out of place suites with new compositions. However, as they are assembled, they comprise a remarkably coherent large-scale form which is also relevant to the given title, Mystery Sonatas.[citation needed]

Rosary devotion

The 15 Mysteries of the Rosary, practised in Rosary processions since the 13th century, are meditations on important moments in the life of Christ and the Virgin Mary. During these processions, followers walked around a cycle of fifteen paintings and sculptures that were placed at specific points of a church or another building. In this tradition, at every point a series of prayers was to be recited and related to the beads on the rosary. The correlation between the fifteen sonatas and fifteen paintings were therefore allowed the composition to be given the title Rosary Sonatas. When they performed this ritual, the faithful also listened to the corresponding biblical passages and commentaries. According to Holman, it is presumed that at the time they would listen to Biber's musical commentary to accompany this ritual of meditation.[3]

Each sonata corresponds to one of the fifteen Mysteries, and a passacaglia for solo violin which closes the collection, possibly relating to the Feast of the Guardian Angel which, at the time, was a celebration that took place on different dates near those of the rosary processions in September and October.[4]

Structure

Just as the 15 Mysteries are divided into three cycles, the 15 sonatas are organized into the same three cycles: five Joyful Mysteries, five Sorrowful Mysteries and five Glorious Mysteries. In the manuscript each of the 15 sonatas is introduced by an engraving appropriate to the devotion to the life of Christ and the Virgin Mary.[3]

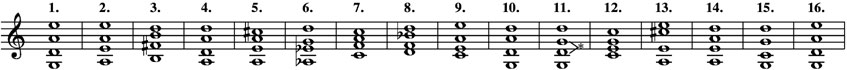

Biber's scordatura helped timbres that were relevant to the themes of each mystery.[3] Apart from the first and last sonatas, each is written with a different scordatura, a technique which provides the instrument with unusual sonorities, colors, altered ranges and new harmonies made available by tuning the strings of the instrument down or up, creating different intervals between the strings than the standard tuning. It was first used in the early 16th century and was most popular until approximately 1750.[5] In literature for strings, scordatura is usually written in a way that the performer reads and plays the notated fingering as if the instrument were tuned conventionally. This means that the performer sees particular notes but hears them differently when played, which can be difficult to perform.[6]

Biber uses scordatura primarily to manipulate the violin's tone color as well as allow for otherwise impossible chords on a violin with standard tuning.[3] Through the progression of the sonatas, scordatura presents a number of difficulties to overcome, with the peak of difficulty located in the Sorrowful Mysteries.[4]

The Joyful Mysteries depict episodes from the early life of Jesus, from the Annunciation to the Finding in the Temple. The last four Joyful Mysteries use tunings with sharps that create bright and resonant harmonies.[citation needed]

In the Sorrowful Mysteries, Biber uses scordatura tunings that tone down the violin's bright sound, creating slight dissonances and compressing the range from the lowest to the highest string. By restricting the range, the violin produces conflicting vibrations that contribute to the expression of tension in the suffering and despair from the Sweating of Blood through to the Crucifixion. The last of the Sorrowful Mysteries, the Crucifixion, uses a more sonorous tuning to underline the significance and awesome emotion within the events of Jesus' last hours of pain.[citation needed]

The Glorious Mysteries include the events from the Resurrection to the Assumption of the Virgin and Coronation of the Virgin. The Resurrection opens the last cycle of sonatas, with the most impressive open and sonorous tuning, underlining its otherworldly theme. The remaining four Glorious Mysteries are also composed using bright, major scordatura tunings.[3]

The closing Passacaglia in G minor uses a bass pattern which is the same as that of the first line of a hymn to the Guardian Angel.[3] Biber’s skill in patterned variation is “surpassed only by the solo violin sonatas of Bach.”[7]

Compositions

| Sonata | Tuning#

IV—III—II—I |

|---|---|

| 1. The Annunciation (standard tuning) | G3—D4—A4—E5 |

| 2. The Visitation | A3—E4—A4—E5 |

| 3. The Nativity | B3—F♯4—B4—D5 |

| 4. The Presentation of the Infant Jesus in the Temple | A3—D4—A4—D5 |

| 5. The Twelve-Year-Old Jesus | A3—E4—A4—C♯5 |

| 6. Christ on the Mount of Olives | A♭3—E♭4—G4—D5 |

| 7. The Scourging at the Pillar | C4—F4—A4—C5 |

| 8. The Crown of Thorns | D4—F4—B♭4—D5 |

| 9. Jesus Carries the Cross | C4—E4—A4—E5 |

| 10. The Crucifixion | G3—D4—A4—D5 |

| 11. The Resurrection (IV—II—III—I)[a] | G3—G4—D4—D5 |

| 12. The Ascension | C4—E4—G4—C5 |

| 13. Pentecost | A3—E4—C♯5—E5 |

| 14. The Assumption of the Virgin | A3—E4—A4—D5 |

| 15. The Coronation of the Virgin | G3—C4—G4—D5 |

| 16. Passacaglia (standard tuning) | G3—D4—A4—E5 |

L ' This table uses standard scientific pitch notation to designate octaves. (In this system "middle C" is called C4.)

- ^ In this unique scordatura the second and third strings are crossed below the bridge and above the top of the neck thereby switching their standard placement on the fingerboard.

Biber's Rosary Sonatas were probably the sole European work to have an influence on early American minimal music. It was through playing them that violinist Tony Conrad formed an interest in alternative tuning, studied the subject, and introduced La Monte Young to just intonation, leading ultimately to the composition of Young's The Well-Tuned Piano, as well as the tuning activities of the Theatre of Eternal Music in general.[8]

Recordings and arrangements

Two recent anniversary celebrations, in 1994 celebrating 350 years since his baptism and in 2004 celebrating 300 years since his death, have led to a “renaissance” of Biber's work through concerts and other forms of presentation.[4] Before then, the Mystery Sonatas were usually enjoyed and studied by Baroque enthusiasts.[9] In 2004, three new recordings emerged by Andrew Manze, Pavlo Beznosiuk and Monica Huggett, showing new interest in this particular work by Biber. The newfound enthusiasm towards the Mystery Sonatas is evident in Eichler's account of Biber's scordatura usage: "Each new configuration is a secret key to an invisible door, unlocking a different set of chordal possibilities on the instrument, opening up alternative worlds of resonance and vibration."[9]

He adds that "Manze makes the strongest impression, not only for the interpretive freedom and vitality in his account but also for the elegantly uncluttered arrangement in which he presents the music, with only keyboard accompaniment (and, on one occasion, cello)." Eichler points out that the Rosary Sonatas are often over-interpreted and taken too literally considering the uncertainty of the original context and intention, and that this restricts the listener's chance to draw from a large variety of possible meanings.[9] Manze himself explains that the tendency of modern performers to use a large bass section as accompaniment is counterproductive to "the music's raison d'être: to evoke an intimate, private atmosphere suitable for prayer and meditation".[4]

Eichler also suggests that the sonatas are best enjoyed when listened to from beginning to end, as a journey that is brought to life through the different varieties of sound and color that the scordatura lends to the instrument.[9]

The Australian chamber trio Latitude 37 performed the complete Rosary Sonatas at the inaugural Brisbane Baroque festival in April 2015.[10]

Also in 2015, Spanish violinist Lina Tur Bonet released her own particular interpretation of the Mystery Sonatas arranged for the ensemble Musica Alchemica and basso continuo.[11]

References

- ^ Dann, Elias; Jiří Sehnal (2020). "Biber, Heinrich Ignaz Franz von". Grove Music Online (8th ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.03037. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0.

- ^ Hill, John Walter (2005). Baroque Music: Music in Western Europe, 1580–1750. New York: Norton.

- ^ a b c d e f g Holman, Peter (2000). Biber: The Mystery Sonatas (PDF). Signum Records. SIGCD021. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Manze, Andrew; Richard Egarr (2004). Biber: The Rosary Sonatas (liner notes). Harmonia Mundi. HMU 907321.22. Archived from the original on 20 March 2012. Retrieved 21 June 2011.

- ^ Randal, Don Michael (2003). The Harvard Dictionary of Music (4th ed.). Cambridge: Belnap Harvard. p. 764. ISBN 0-674-01163-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Boyden, David D.; Robin Stowell; Mark Chambers; James Tyler; Richard Partridge (2001). "Scordatura [descordato, discordato] (It., from scordare: 'to mistune'; Fr. discordé, discordable, discordant; Ger. Umstimmung, Verstimmung)". Grove Music Online (8th ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.41698. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0.

- ^ Bukofzer, Manfred (1947). Music in the Baroque Era. New York: W.W. Norton. pp. 115–116. ISBN 0393097455.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Kyle Gann (2006). Music Downtown: Writings from the Village Voice. University of California Press. p. 204. ISBN 9780520935938. Originally published in The Village Voice, 28 April 1998, vol. XLIII, no. 17, pp. 141, 145

- ^ a b c d Eichler, Jeremy (2011). "Reciting a Rosary, but in Sonata Form". The New York Times.

- ^ Martin Buzacott (16 April 2015). "Brisbane Baroque: Hardheads seen to weep". The Australian. Retrieved 2 March 2024.

- ^ Biber: Mystery Sonatas playlist on YouTube

Further reading

- Arnold, Denis; Basil Smallman (2011) [2002]. "Biber, Heinrich Ignaz Franz von". In Alison Latham (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Music. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199579037.