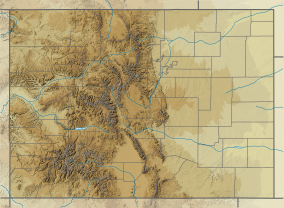

Rocky Mountain National Park

| Rocky Mountain National Park | |

|---|---|

View from Bear Lake in Rocky Mountain National Park | |

| Location | Larimer / Grand / Boulder counties, Colorado, United States |

| Nearest city | Estes Park and Grand Lake, Colorado |

| Coordinates | 40°20′48″N 105°44′11″W / 40.3466°N 105.7364°W |

| Area | 265,461 acres (1,074.28 km2)[2] |

| Established | January 26, 1915[3] |

| Visitors | 4,300,424 (in 2022)[4] |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | Rocky Mountain National Park |

Rocky Mountain National Park is a national park of the United States located approximately 55 mi (89 km) northwest of Denver[5] in north-central Colorado, within the Front Range of the Rocky Mountains. The park is situated between the towns of Estes Park to the east and Grand Lake to the west. The eastern and western slopes of the Continental Divide run directly through the center of the park with the headwaters of the Colorado River located in the park's northwestern region.[6] The main features of the park include mountains, alpine lakes and a wide variety of wildlife within various climates and environments, from wooded forests to mountain tundra.

The Rocky Mountain National Park Act was signed by President Woodrow Wilson on January 26, 1915, establishing the park boundaries and protecting the area for future generations.[3] The Civilian Conservation Corps built the main automobile route, Trail Ridge Road, in the 1930s.[3] In 1976, UNESCO designated the park as one of the first World Biosphere Reserves.[7] In 2023, 4.1 million recreational visitors entered the park.[8] The park is one of the most visited in the National Park System, ranking as the third most visited national park in 2015.[9] In 2019, the park saw record attendance yet again with 4,678,804 visitors, a 44% increase since 2012.[10]

The park has five visitor centers,[11] with park headquarters located at the Beaver Meadows Visitor Center—a National Historic Landmark designed by the Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture at Taliesin West.[12] National Forest lands surround the park on all sides, including Roosevelt National Forest to the north and east, Routt National Forest to the north and west, and Arapaho National Forest to the west and south, with the Indian Peaks Wilderness area located directly south of the park.[6]

History

The history of Rocky Mountain National Park began when Paleo-Indians traveled along what is now Trail Ridge Road to hunt and forage for food.[13] Ute and Arapaho people subsequently hunted and camped in the area.[14][15] In 1820, the Long Expedition, led by Stephen H. Long for whom Longs Peak was named, approached the Rockies via the Platte River.[16][17] Settlers began arriving in the mid-1800s,[18] displacing the Native Americans who mostly left the area voluntarily by 1860,[19] while others were removed to reservations by 1878.[15]

Lulu City, Dutchtown, and Gaskill in the Never Summer Mountains were established in the 1870s when prospectors came in search of gold and silver.[20] The boom ended by 1883 with miners deserting their claims.[21] The railroad reached Lyons, Colorado in 1881 and the Big Thompson Canyon Road—a section of U.S. Route 34 from Loveland to Estes Park—was completed in 1904.[22] The 1920s saw a boom in building lodges, including the Bear Lake Trail School, and roads in the park, culminating with the construction of Trail Ridge Road to Fall River Pass between 1929 and 1932, then to Grand Lake by 1938.[23]

Prominent individuals in the effort to create a national park included Enos Mills from the Estes Park area, James Grafton Rogers from Denver, and J. Horace McFarland of Pennsylvania.[24] The national park was established on January 26, 1915.[3]

Geography

Rocky Mountain National Park encompasses 265,461 acres (414.78 sq mi; 1,074.28 km2) of federal land,[2] with an additional 253,059 acres (395.40 sq mi; 1,024.09 km2) of U.S. Forest Service wilderness adjoining the park boundaries.[25] The Continental Divide runs generally north–south through the center of the park,[26] with rivers and streams on the western side of the divide flowing toward the Pacific Ocean while those on the eastern side flow toward the Atlantic.[27]

A geographical anomaly is found along the slopes of the Never Summer Mountains where the Continental Divide forms a horseshoe–shaped bend for about 6 miles (9.7 km), heading from south–to–north but then curving sharply southward and westward out of the park.[6][28] The sharp bend results in streams on the eastern slopes of the range joining the headwaters of the Colorado River that flow south and west, eventually reaching the Pacific.[6][29] Meanwhile, streams on the western slopes join rivers that flow north and then east and south, eventually reaching the Atlantic.[6][29]

The headwaters of the Colorado River are located in the park's northwestern region.[26] The park contains approximately 450 miles (724 km) of rivers and streams, 350 miles (563 km) of trails, and 150 lakes.[26][30]

Rocky Mountain National Park is one of the highest national parks in the nation, with elevations from 7,860 to 14,259 feet (2,396 to 4,346 m),[31] the highest point of which is Longs Peak.[32] Trail Ridge Road is the highest paved through-road in the country, with a peak elevation of 12,183 feet (3,713 m).[33] Sixty mountain peaks over 12,000 feet (3,658 m) high provide scenic vistas.[31] On the north side of the park, the Mummy Range contains a number of thirteener peaks, including Hagues Peak, Mummy Mountain, Fairchild Mountain, Ypsilon Mountain, and Mount Chiquita.[34] Several small glaciers and permanent snowfields are found in the high mountain cirques.[35]

There are five regions, or geographical zones, within the park.

Region 1: Moose and big meadows

Region 1 is known for moose and big meadows and is located on the west, or Grand Lake, side of the Continental Divide.[36] Thirty miles of the Continental Divide National Scenic Trail loop through the park and pass through alpine tundra and scenery.[37]

The Big Meadows area with its grasses and wildflowers can be reached via the Onahu, Tonahutu, or Green Mountain trail. Other scenic areas include Long Meadows and the Kawuneeche Valley (Coyote Valley) of the upper Colorado River which is a good place for birdwatching, as well as snowshoeing and cross-country skiing in winter. The valley trail loops through Kawuneeche Valley[37] which contained as many as 39 mines, though less than 20 of those have archived records and archeological remains.[38] LuLu City is the site of an abandoned silver mining town of the early 1880s located along the Colorado River Trail.[6] According to a 1985 report prepared for the NRHP, there were only three cabin ruins remaining along with remnants of six other buildings.[39]

Baker Pass crosses the Continental Divide through the Never Summer Mountains and into the Michigan River drainage to the west of Mount Nimbus[37]—a drainage that feeds streams and rivers that drain into the Gulf of Mexico.[29] Other mountain passes are La Poudre Pass and Thunder Pass, which was once used by stage coaches and is a route to Michigan Lakes. Little Yellowstone has geological features similar to the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone. The Green Mountain trail once was a wagon road used to haul hay from Big Meadows. Flattop Mountain, which can be accessed from the eastern and western sides of the park, is near Green Mountain. Shadow Mountain Lookout—a wildfire observation tower—is on the National Register of Historic Places.[37] Paradise Park Natural Area is an essentially hidden and protected wild area with no maintained trails penetrating it.[40]

Skeleton Gulch, Cascade Falls, North Inlet Falls, Granite Falls, and Adams Falls are found in the west side of the park. The west side lakes include Bowen Lake, Lake Verna, Lake of the Clouds, Haynach Lakes, Timber Lake, Lone Pine Lake, Lake Nanita, and Lake Nokoni.[37]

Region 2: Alpine region

Region 2 is the alpine region of the park with accessible tundra trails at high elevations—an area known for its spectacular vistas.[36] Within this region is Mount Ida, with tundra slopes and a wide-open view of the Continental Divide. Forest Canyon Pass is near the top of the Old Ute Trail that once linked villages across the Continental Divide.[41]

Chapin Pass trail traverses a dense forest to beautiful views of the Chapin Creek valley, proceeding onward above timberline to the western flank of Mount Chapin. Tundra Communities Trail, accessible from Trail Ridge Road, is a hike offering tundra views and alpine wildflowers. Other trails are Tombstone Ridge and Ute Trail, which starts at the tundra and is mostly downhill from Ute Crossing to Upper Beaver Meadows, with one backcountry camping site. Cache La Poudre River trail begins north of Poudre Lake on the west side of the valley near Milner Pass and heads downward toward the Mummy Pass trail junction. Lake Irene is a recreation and picnic area.[41]

Region 3: Wilderness

Region 3, known for wilderness escape, is in the northern part of the park and is accessed from the Estes Park area.[36]

The Mummy Range is a short mountain range in the north of the park. The Mummies tend to be gentler and more forested than the other peaks in the park, though some slopes are rugged and heavily glaciated, particularly around Ypsilon Mountain and Mummy Mountain. Bridal Veil Falls is a scenic point and trail accessible from the Cow Creek trailhead, at the Continental Divide Research Center.[42] West Creek Falls and Chasm Falls, near Old Fall River Road, are also in this region. The Alluvial Fan trail leads to a bridge over the river that had been the site of the Lawn Lake Flood.[43]

Lumpy Ridge Trail leads to Paul Bunyan's Boot at about 1.5 mi (2.4 km) from the trailhead, then Gem Lake, and a further 2.2 mi (3.5 km) to Balanced Rock.[44] Black Canyon Trail intersects Cow Creek Trail, forming part of the Gem Lake loop which goes through the old McGregor Ranch valley, passing Lumpy Ridge rock formations, with a loop hike that goes into the McGraw Ranch valley.[43]

Cow Creek Trail follows Cow Creek, with its many beaver ponds, extending past the Bridal Falls turnoff as the Dark Mountain trail, then joining the Black Canyon trail to intersect the Lawn Lake trail shortly below the lake.[43] North Boundary Trail connects to the Lost Lake trail system. North Fork Trail begins outside of the park in the Comanche Peak Wilderness before reaching the park boundary and ending at Lost Lake. Stormy Peaks Trail connects Colorado State University's Pingree Park campus in the Comanche Peak Wilderness and the North Fork Trail inside the park.[43]

Beaver Mountain Loop, also used by horseback riders, passes through forests and meadows, crosses Beaver Brook and several aspen-filled drainages, and has a great view of Longs Peak.[43] Deer Mountain Trail gives a 360 degree view of eastern part of the park. The summit plateau of Deer Mountain offers expansive views of the Continental Divide. During the winter, the lower trail generally has little snow, though packed and drifted snow are to be expected on the switchbacks. Snow cover on the summit may be three to five feet deep, requiring the use of snowshoes or skis.[43]

The trail to Lake Estes in Estes Park meanders through a bird sanctuary, beside a golf course, along the Big Thompson River and Fish Creek, through the lakeside picnic area and along the lakeshore. The trail is used by birdwatchers, bikers and hikers.[43]

Lawn Lake Trail climbs to Lawn Lake and Crystal Lake, one of the parks deepest lakes, in the alpine ecosystem and along the course of the Roaring River. The river shows the massive damage caused by a dam failure in 1982 that claimed the lives of three campers. The trail is a strenuous snowshoe hike in the winter.[43] Ypsilon Lake Trail leads to its namesake as well as Chipmunk Lake, with views of Longs Peak, while traversing pine forests with grouseberry and bearberry bushes. The trail also offers views of the canyon gouged out by rampaging water that broke loose from Lawn Lake Dam in 1982. Visible is the south face of Ypsilon Mountain, with its Y-shaped gash rising sharply from the shoreline.[43]

Gem Lake is high among the rounded granite domes of Lumpy Ridge. Untouched by glaciation, this outcrop of 1.8 billion-year-old granite has been sculpted by wind and chemical erosion into a backbone-like ridge. Pillars, potholes, and balanced rocks are found around the midpoint of the trail, along with views of the Estes Valley and Continental Divide.[43] Potts Puddle trail is accessible from the Black Canyon trail.[43]

Region 4: Heart of the park

Region 4 is the heart of the park with easy road and trail access, great views, and lake hikes including the most popular trails.[36] Flattop Mountain is a tundra hike and the easiest hike to the Continental Divide in the park. Crossing over Flattop Mountain, the hike to Hallett Peak passes through three climate zones, traversing the ridge that supports Tyndall Glacier and finally ascending to the summit of Hallett Peak.[45]

Bear Lake is a high-elevation lake in a spruce and fir forest at the base of Hallett Peak and Flattop Mountain.[45] Bierstadt Lake sits atop a lateral moraine named Bierstadt Moraine, and drains into Mill Creek. There are several trails that lead to Bierstadt Lake through groves of aspens and lodgepole pines.[46] North of Bierstadt Moraine is Hollowell Park, a large and marshy meadow along Mill Creek. The Hollowell Park trail runs along Steep Mountain's south side. Ranches, lumber and sawmill enterprises operated in Hollowell Park into the early 1900s.[46]

Glacial Basin was the site of a resort run by Abner and Alberta Sprague, after whom Sprague Lake is named. The lake is a shallow body of water that was created when the Spragues dammed Boulder Brook to create a fish pond. Sprague Lake is a popular place for birdwatching, hiking and viewing the mountain peaks, along with camping at the Glacier Basin campground.[47]

Dream Lake is one of the most-photographed lakes and is also noted for its winter snowshoeing. Emerald Lake is located directly below the saddle between Hallett Peak and Flattop Mountain, only a short hike beyond Dream Lake.[45] The shore of Lake Haiyaha (a Native American word for "big rocks") is surrounded by boulders along with ancient, twisted and picturesque pine trees growing out of rock crevices. Nymph Lake is named for the yellow lily, Nymphaea polysepala, on its surface. Lake Helene is at the head of Odessa Gorge, east of Notchtop Mountain. Two Rivers Lake is found along the hike to Odessa Lake from Bear Lake, and has one backcountry campsite. The Cub Lake trail passes Big Thompson River, flowery meadows, and stands of pine and aspen trees. Ice and deep snow are present during the winter, requiring the use of skis or snowshoes.[45]

The Fern Lake trail passes Arch Rock formations, The Pool, and the cascading water of Fern Falls. Two backcountry campsites are located near the lake, and two more are closer to the trailhead. Odessa Lake has two approaches: one is along the Flattop trail from Bear Lake while the other is from the Fern Lake trailhead, along which are Fern Creek, The Pool, Fern Falls, and Fern Lake itself. One backcountry campsite is available.[45] Other lakes are Jewel Lake, Mills Lake, Black Lake, Blue Lake, Lake of Glass, Sky Pond, and Spruce Lake.[45]

The Pool is a large turbulent water pocket formed below where Spruce and Fern Creeks join the Big Thompson River. The winter route is along a gravel road, which leads to a trail at the Fern Lake trailhead. Along the route are beaver-cut aspen, frozen waterfalls on the cliffs, and the Arch Rocks.[45] The trail to Alberta Falls runs by Glacier Creek and Glacier Gorge.[45]

Wind River Trail leaves the East Portal and follows the Wind River to join with the Storm Pass trail. There are three backcountry campsites.[45] Other sites in the area are The Loch, Loch Vale, Mill Creek Basin, Andrews Glacier, Sky Point, Timberline Falls, Upper Beaver Meadows, and Storm Pass.[45]

Region 5: Waterfalls and backcountry

Region 5, known for waterfalls and backcountry, is south of Estes Park and contains Longs Peak—the park's iconic fourteener—and the Wild Basin area.[36] Other peaks and passes include Lily Mountain, Estes Cone, Twin Sisters, Boulder-Grand Pass, and Granite Pass.[48] Eugenia Mine operated about the late-19th to early-20th century, with some old equipment and a log cabin remaining.[48] Sites and trails include Boulder Field, Wild Basin Trail, and Homer Rouse Memorial Trail.[48]

Enos Mills, the main figure behind the creation of Rocky Mountain National Park, enjoyed walking to Lily Lake from his nearby cabin. Wildflowers are common in the spring and early summer. In the winter, the trail around the lake is often suitable for walking in boots, or as a short snowshoe or ski. Other lakes in the Wild Basin include Chasm Lake, Snowbank Lake, Lion Lakes 1 and 2, Thunder Lake, Ouzel Lake, Finch Lake, Bluebird Lake, Pear Lake, and Sandbeach Lake. Many of the lakes have backcountry campsites. Waterfalls include Ouzel Falls, Trio Falls, Copeland Falls, and Calypso Cascades.[48]

Climate

According to the Köppen climate classification system, Rocky Mountain National Park has a Subarctic climate with cool summers and year around precipitation (Dfc). According to the United States Department of Agriculture, the Plant Hardiness zone at Bear Lake Ranger Station (9492 ft / 2893 m) is 5a with an average annual extreme minimum temperature of -15.2 °F (-26.2 °C), and 5a with an average annual extreme minimum temperature of -16.1 °F (-26.7 °C) at Beaver Meadows Visitor Center (7825 ft / 2385 m).[49]

The complex interactions of elevation, slope, exposure and regional-scale air masses determine the climate within the park,[50][51] which is noted for its extreme weather patterns.[51] A "collision of air masses" from several directions produces some of the key weather events in the region. When cold arctic air from the north meets warm moist air from the Gulf of Mexico at the Front Range, "intense, very wet snowfalls with total snow depth measured in the feet" accumulate in the park.[50]

| Climate data for Bear Lake Ranger Station, Rocky Mountain National Park. Elev: 9583 ft (2921 m) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 28.6 (−1.9) |

30.8 (−0.7) |

37.5 (3.1) |

44.1 (6.7) |

53.2 (11.8) |

63.7 (17.6) |

70.7 (21.5) |

68.6 (20.3) |

60.7 (15.9) |

49.2 (9.6) |

36.0 (2.2) |

28.3 (−2.1) |

47.7 (8.7) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 20.1 (−6.6) |

21.2 (−6.0) |

26.9 (−2.8) |

33.0 (0.6) |

41.5 (5.3) |

50.5 (10.3) |

56.9 (13.8) |

55.4 (13.0) |

48.2 (9.0) |

38.6 (3.7) |

27.4 (−2.6) |

20.0 (−6.7) |

36.7 (2.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 11.6 (−11.3) |

11.7 (−11.3) |

16.2 (−8.8) |

21.8 (−5.7) |

29.7 (−1.3) |

37.2 (2.9) |

43.0 (6.1) |

42.1 (5.6) |

35.6 (2.0) |

28.0 (−2.2) |

18.9 (−7.3) |

11.6 (−11.3) |

25.7 (−3.5) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.72 (69) |

2.97 (75) |

3.83 (97) |

4.34 (110) |

3.39 (86) |

2.11 (54) |

2.21 (56) |

2.20 (56) |

2.10 (53) |

2.39 (61) |

3.04 (77) |

3.11 (79) |

34.41 (874) |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 56.5 | 56.4 | 54.3 | 54.3 | 55.2 | 50.1 | 48.6 | 54.2 | 50.0 | 47.2 | 52.5 | 57.3 | 53.0 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 7.1 (−13.8) |

8.1 (−13.3) |

12.6 (−10.8) |

18.3 (−7.6) |

26.6 (−3.0) |

32.6 (0.3) |

37.7 (3.2) |

39.1 (3.9) |

30.4 (−0.9) |

20.2 (−6.6) |

12.3 (−10.9) |

7.3 (−13.7) |

21.1 (−6.1) |

| Source: PRISM Climate Group[52] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Beaver Meadows Visitor Center, Rocky Mountain National Park. Elev: 7877 ft (2401 m) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 36.4 (2.4) |

38.4 (3.6) |

44.2 (6.8) |

50.7 (10.4) |

60.1 (15.6) |

71.2 (21.8) |

78.1 (25.6) |

76.1 (24.5) |

68.1 (20.1) |

56.7 (13.7) |

43.5 (6.4) |

35.9 (2.2) |

55.0 (12.8) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 25.8 (−3.4) |

26.9 (−2.8) |

32.4 (0.2) |

38.4 (3.6) |

47.0 (8.3) |

56.1 (13.4) |

62.4 (16.9) |

60.6 (15.9) |

53.0 (11.7) |

43.5 (6.4) |

33.0 (0.6) |

25.7 (−3.5) |

42.1 (5.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 15.1 (−9.4) |

15.5 (−9.2) |

20.6 (−6.3) |

26.1 (−3.3) |

34.0 (1.1) |

40.9 (4.9) |

46.6 (8.1) |

45.1 (7.3) |

37.9 (3.3) |

30.3 (−0.9) |

22.6 (−5.2) |

15.6 (−9.1) |

29.3 (−1.5) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.76 (19) |

0.81 (21) |

1.94 (49) |

2.36 (60) |

2.48 (63) |

1.99 (51) |

2.39 (61) |

2.02 (51) |

1.46 (37) |

1.04 (26) |

0.87 (22) |

0.83 (21) |

18.95 (481) |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 46.3 | 46.9 | 48.0 | 47.8 | 50.6 | 45.3 | 45.6 | 49.7 | 46.1 | 42.9 | 44.5 | 47.8 | 46.8 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 8.0 (−13.3) |

9.3 (−12.6) |

14.9 (−9.5) |

20.3 (−6.5) |

29.6 (−1.3) |

35.2 (1.8) |

41.1 (5.1) |

41.7 (5.4) |

32.8 (0.4) |

22.4 (−5.3) |

13.7 (−10.2) |

8.6 (−13.0) |

23.2 (−4.9) |

| Source: PRISM Climate Group[52] | |||||||||||||

Elevation

Higher elevation areas within the park receive twice as much precipitation as lower elevation areas, generally in the form of deep winter snowfall.[50] Arctic conditions are prevalent during the winter, with sudden blizzards, high winds, and deep snowpack. High country overnight trips require gear suitable for -35 °F or below.[51]

The subalpine region does not begin to experience spring-like conditions until June. Wildflowers bloom from late June to early August.[51]

Below 9,400 feet (2,865 m), temperatures are often moderate, although nighttime temperatures are cool, as is typical of mountain weather.[51] Spring comes to the montane area by early May, when wildflowers begin to bloom. Spring weather is subject to unpredictable changes in temperature and precipitation, with potential for snow along trails through May.[51] In July and August, temperatures are generally in the 70s or 80s °F during the day, and as low as the 40s °F at night.[51] Lower elevations receive rain as most of their summer precipitation.[50]

Sudden dramatic changes in the weather may occur during the summer, typically due to afternoon thunderstorms that can cause as much as a 20 °F drop in temperature and windy conditions.[51]

Continental Divide

The park's climate is also affected by the Continental Divide, which runs northwest to southeast through the center of the park atop the high peaks. The Continental Divide creates two distinct climate patterns - one typical of the east side near Estes Park and the other associated with the Grand Lake area on the park's west side.[51] The west side of the park experiences more snow, less wind, and clear cold days during the winter months.[51]

Climate change study

Rocky Mountain National Park was selected to participate in a climate change study, along with two other National Park Service areas in the Rocky Mountain region and three in the Appalachian Mountain region.[53] The study began in 2011, orchestrated by members of the academic scientific community in cooperation with the National Park Service and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA).[53] The stated objective: "develop and apply decision support tools that use NASA and other data and models to assess vulnerability of ecosystems and species to climate and land use change and evaluate management options."[54]

As of 2010, the preceding one hundred years of records indicated an increase in the average annual temperature of approximately 3 °F (1.7 °C).[50][55][a] The average low temperature has increased more than the average high temperature during the same time period.[50] As a result of the temperature increase, snow is melting from the mountains earlier in the year, leading to drier summers and probably to an earlier, longer fire season.[50] Since the 1990s, mountain pine beetles have reproduced more rapidly and have not died off at their previous mortality rate during the winter months. Consequently, the increased beetle population has led to an increased rate of tree mortality in the park.[56]

The climate change study projects further temperature increases, with greater warming in the summer and higher extreme temperatures by 2050. Due to the increased temperature, there is a projected moderate increase in the rate of water evaporation. Reduced snowfall—perhaps 15% to 30% less than current amounts—and the elimination of surface hail, along with the higher likelihood of intense precipitation events are predicted by 2050. Droughts may be more likely due to increased temperatures, increased evaporation rates, and potential changes in precipitation.[56]

Geology

Precambrian metamorphic rock formed the core of the North American continent during the Precambrian eon 4.5–1 billion years ago. During the Paleozoic era, western North America was submerged beneath a shallow sea, with a seabed composed of limestone and dolomite deposits many kilometers thick.[57] Pikes Peak granite formed during the late Precambrian eon, continuing well into the Paleozoic era, when mass quantities of molten rock flowed, amalgamated, and formed the continents about 1 billion–300 million years ago. Concurrently, in the period from 500 to 300 million years ago, the region began to sink while lime and mud sediments were deposited in the vacated space. Eroded granite produced sand particles that formed strata—layers of sediment—in the sinking basin.[58]: 1

About 300 million years ago, the land was uplifted creating the ancestral Rocky Mountains.[58]: 1 Fountain Formation was deposited during the Pennsylvanian period of the Paleozoic era, 290–296 million years ago. Over the next 150 million years, the mountains uplifted, continued to erode, and covered themselves in their own sediment. Wind, gravity, rainwater, snow, and glacial ice eroded the granite mountains over geologic time scales.[58]: 6 The Ancestral Rockies were eventually buried under subsequent strata.[58]: 10

The Pierre Shale formation was deposited during the Paleogene and Cretaceous periods about 70 million years ago. The region was covered by a deep sea—the Cretaceous Western Interior Seaway—which deposited massive amounts of shale on the seabed. Both the thick stratum of shale and embedded marine life fossils—including ammonites and skeletons of fish and such marine reptiles as mosasaurs, plesiosaurs, and extinct species of sea turtles, along with rare dinosaur and bird remains—were created during this time period. The area now known as Colorado was eventually transformed from being at the bottom of an ocean to dry land again, giving yield to another fossiliferous rock layer known as the Denver Formation.[58]: 16

At about 68 million years ago, the Front Range began to rise again due to the Laramide orogeny in the west.[58]: 16, [59]: 8 During the Cenozoic era, block uplift formed the present Rocky Mountains. The geologic composition of Rocky Mountain National Park was also affected by deformation and erosion during that era. The uplift disrupted the older drainage patterns and created the present drainage patterns.[59]: 8–9

Glaciation

Glacial geology in Rocky Mountain National Park can be seen from the mountain peaks to the valley floors. Ice is a powerful sculptor of this natural environment and large masses of moving ice are the most powerful tools. Telltale marks of giant glaciers can be seen all throughout the park. Streams and glaciations during the Quaternary period cut through the older sediment, creating mesa tops and alluvial plains, and revealing the present Rocky Mountains.[58]: 30 The glaciation removed as much as 5,000 feet (1,500 m) of sedimentary rocks from earlier inland sea deposits. This erosion exposed the basement rock of the Ancestral Rockies. Evidence of the uplifting and erosion can be found on the way to Rocky Mountain National Park in the hogbacks of the Front Range foothills.[59]: 8–9 Many sedimentary rocks from the Paleozoic and Mesozoic eras exist in the basins surrounding the park.[60]

While the glaciation periods are largely in the past, the park still has several small glaciers.[61] The glaciers include Andrews, Sprague, Tyndall, Taylor, Rowe, Mills, and Moomaw Glaciers.[35]

Ecology

According to the A. W. Kuchler U.S. Potential natural vegetation Types, Rocky Mountain National Park encompasses three classifications; an Alpine tundra & Barren (52) vegetation type with an Alpine tundra (11) vegetation form, a Western Spruce/Fir (15) vegetation type with a Rocky Mountain Conifer Forest (3) vegetation form, and a Pine/Douglas fir (18) vegetation type with a Rocky Mountain Conifer Forest (3) vegetation form.[62]

Colorado has one of the most diverse plant and animal environments of the United States, partially due to the dramatic temperature differences arising from varying elevation levels and topography. In dry climates, the average temperature drops 5.4 degrees Fahrenheit with every 1,000 foot increase in elevation (9.8 degrees Celsius per 1,000 meters). Most of Colorado is semi-arid with the mountains receiving the greatest amount of precipitation in the state.[63]

The Continental Divide runs north to south through the park, creating a climatic division. Ancient glaciers carved the topography into a range of ecological zones.[31] The east side of the Divide tends to be drier with heavily glaciated peaks and cirques. The west side of the park is wetter with more lush, deep forests.[64]

There are four ecosystems, or zones, in Rocky Mountain National Park: montane, subalpine, alpine tundra, and riparian. The riparian zone occurs throughout all of the three other zones. Each individual ecosystem is composed of organisms interacting with one other and with their surrounding environment. Living organisms (biotic), along with the dead organic matter they produce, and the abiotic (non-living) environment that impacts those living organisms (water, weather, rocks, and landscape) are all members of an ecosystem.[65]

The park was designated a World Biosphere Reserve by the United Nations in 1976 to protect its natural resources.[66][67] The park's biodiversity includes afforestation and reforestation, ecology, inland bodies of water, and mammals, while its ecosystems are managed for nature conservation, environmental education and public recreation purposes.[66] The areas of research and monitoring include ungulate ecology and management, high-altitude revegetation, global change, acid precipitation effects, and aquatic ecology and management.[66]

Despite the importance of preserving the park's natural environment, the area suffers air pollution impacts from Front Range activities,[68] even as the impacts of Denver's infamous brown cloud[69] have been reduced.[70]

Montane zone

The montane ecosystem is at the lowest elevations in the park, between 5,600 to 9,500 feet (1,700 to 2,900 m), where the slopes and large meadow valleys support the widest range of plant and animal life,[71][72] including montane forests, grasslands, and shrublands. The area has meandering rivers[72] and during the summer, wildflowers grow in the open meadows. Ponderosa pine trees, grass, shrubs and herbs live on dry, south-facing slopes. North-facing slopes retain moisture better than those that face south. The soil better supports dense populations of trees, like Douglas fir, lodgepole pine, and ponderosa pine. There are also occasional Engelmann spruce and blue spruce trees. Quaking aspens thrive in high-moisture montane soils. Other water-loving small trees like willows, grey alder, and water birch may be found along streams or lakeshores. Water-logged soil in flat montane valleys may be unable to support growth of evergreen forests.[72] The following areas are part of the montane ecosystem: Moraine Park, Horseshoe Park, Kawuneeche Valley, and Upper Beaver Meadows.[72]

Some of the mammals that inhabit the montane ecosystem include snowshoe hares, coyotes, cougars, beavers, mule deer, moose, bighorn sheep, black bears, and Rocky Mountain elk.[72] During the fall, visitors often flock to the park to witness the elk rut.[73]

Subalpine zone

From 9,000 ft (2,700 m) to 11,000 ft (3,400 m),[74] the montane forests give way to subalpine forests.[71] Forests of fir and Engelmann spruce cover the mountainsides in subalpine areas. Trees grow straight and tall in the lower subalpine forests, but become shorter and more deformed the nearer they are to the tree line.[74] At the tree line, seedlings may germinate on the lee side of rocks and grow only as high as the rock provides wind protection, with any further growth being more horizontal than vertical. The low growth of dense trees is called krummholz, which may become well-established and live for several hundred to a thousand years old.[74]

In the subalpine zone, lodgepole pines and huckleberry have established themselves in previous burn areas. Crystal clear lakes and fields of wildflowers are hidden among the trees. Mammals of the subalpine zone include bobcats, cougars, coyotes, elk, mule deer, chipmunks, shrews, porcupines and yellow-bellied marmots. Black bears are attracted by the berries and seeds of subalpine forests. Clark's nutcracker, Steller's jay, mountain chickadee and yellow-rumped warbler are some of the many birds found in the subalpine zone.[74] Sprague Lake and Odessa Lake are two of the park's subalpine lakes.[74]

Alpine tundra

Above tree line, at approximately 11,000 ft (3,400 m), trees disappear and the vast alpine tundra takes over.[71] Over one third of the park resides above the tree line, an area which limits plant growth due to the cold climate and strong winds. The few plants that can survive under such extreme conditions are mostly perennials. Many alpine plants are dwarfed at high elevations, though their occasional blossoms may be full-sized.[75]

Cushion plants have long taproots that extend deep into the rocky soil. Their diminutive size, like clumps of moss, limits the effect of harsh winds. Many flowering plants of the tundra have dense hairs on stems and leaves to provide wind protection or red-colored pigments capable of converting the sun's light rays into heat. Some plants take two or more years to form flower buds, which survive the winter below the surface and then open and produce fruit with seeds in the few weeks of summer. Grasses and sedges are common where tundra soil is well-developed.[75]

Non-flowering lichens cling to rocks and soil. Their enclosed algal cells can photosynthesize at any temperature above 32 degrees Fahrenheit (0 °C), and the outer fungal layers can absorb more than their own weight in water. Adaptations for survival amidst drying winds and cold temperatures may make tundra vegetation seem very hardy, but in some respects it remains very fragile. Footsteps can destroy tundra plants and it may take hundreds of years to recover.[75] Mammals that live on the alpine tundra, or visit during the summer season, include bighorn sheep, elk, badgers, pikas, yellow-bellied marmots, and snowshoe hares. Birds include prairie falcons, white-tailed ptarmigans, and common ravens. Flowering plants include mertensia, sky pilot, alpine sunflowers, alpine dwarf columbine, and alpine forget-me-not. Grasses include kobresia, spike trisetum, spreading wheatgrass, and tufted hairgrass.[75]

Riparian zone

The riparian ecosystem runs through the montane, subalpine, and alpine tundra zones and creates a foundation for life, especially for species that thrive next to streams, rivers, and lakes.[76] The headwaters of the Colorado River, which provides water to many of the southwestern states, are located on the west side of the park. The Fall River, Cache la Poudre River and Big Thompson Rivers are located on the east side of the park. Just like the other ecosystems in the park, the riparian zone is affected by the climatic variables of temperature, precipitation, and elevation. Generally, riparian zones in valleys will have cooler temperatures than communities located on slopes and ridge tops. Depending on elevation, a riparian zone may have more or less precipitation than other riparian zones in the park, with the difference creating a shift in the types of plants and animals found in a specific zone.[77]

Wildlife

Rocky Mountain National Park is home to many species of animals, including nearly seventy mammals and almost three hundred species of birds. This diversity is due to the park's varying topography, which creates a variety of habitats. However, some species have been extirpated from the park, including gray wolf, wolverine, grizzly bear, and American bison. Moose are commonly seen in the park, but they were not historically recorded as being part of this particular area of the Rocky Mountains.[78]

Elk

The park is home to some 2,000 to 3,000 elk in summer, and between 800 and 1,000 elk spend the winter within its boundaries. Because of lack of predators such as wolves, the National Park Service culls around 50 elk each winter.[79] Overgrazing by elk has become a major problem in the park's riparian areas, so much so that the NPS fences them out of many critical wetland habitats to let willows and aspens grow. The program seems to be working, as the deciduous wetland plants thrive within the fencing. Many people think the elk herd is too large, but are reluctant to reintroduce predators because of its proximity to large human populations and ranches.[80]

Other ungulates

Many other ungulates reside in the park, including bighorn sheep, moose, and mule deer. Bison were eliminated from the park in the 1800s, as were pronghorn and moose, the latter of which was restored to the area in 1978. Moose are now frequently seen in the park, especially on the park's west side.[81] The park's bighorn sheep population has recovered and is estimated at 350 animals.[82]

Predators

The park is home to many predatory animals, including Canada lynx, foxes, bobcat, cougar, black bear, and coyotes. Wolves and grizzly bears were extirpated in the early 1900s. Most of these predators kill smaller animals, but mountain lions and coyotes kill deer and occasionally elk. Bears also eat larger prey. Moose have no predators in the park. Black bears are relatively uncommon in the park, numbering only 24-35 animals. They also have fewer cubs and the bears seem skinnier than they do in most areas.[83] Canadian lynx are quite rare within the park, and they have probably spread north from the San Juan Mountains, where they were reintroduced in 1999. Cougars feed mainly on mule deer in the park, and live 10–13 years. Cougar territories can be as large as 500 square miles (1,300 km2).[84] Coyotes hunt both alone and in pairs, but occasionally hunt in packs. They mainly feed on rodents but occasionally bring down larger animals, including deer, and especially fawns and elk calves. Scat studies in Moraine Park showed that their primary foods were deer and rodents. They form strong family bonds and are very vocal.[85]

Recreational activities

The park contains a network of trails that range from easy, paved paths suitable for all visitors including those with disabilities, to strenuous mountain trails for experienced, conditioned hikers as well as off-trail routes for backcountry hikes. Trails lead to more than 100 designated wilderness camping sites.[86] From either the Bear Lake or Grand Lake trailheads, backpackers can hike a 45 mi (72 km) loop along the Continental Divide National Scenic Trail within the park.[87] Most trails are for summer use only, since at other times of the year many trails are not safe due to weather conditions.[88] Horseback riding is permitted on most trails,[89] as are llamas and other pack animals.[90]

Rock climbing and mountaineering opportunities include Lumpy Ridge,[91] Hallett Peak, Chiefs Head Peak, and Longs Peak, the highest peak in the park, with the easiest route being the Keyhole Route. This 8 mi (13 km) one-way climb has an elevation gain of 4,850 ft (1,480 m). The vast east face, including the area known as The Diamond, is home to many classic big wall rock climbing routes. Many of the highest peaks have technical ice and rock routes on them, ranging from short scrambles to long multi-pitch climbs.[92] Bouldering is popular in the park as well, as it is often considered a "mecca for boulderers around the world", particularly the Emerald Lake and Chaos Canyon areas.[93]

Fishing is permitted at many of the park's lakes and streams. Four trout species inhabit park waters: rainbow, brook, cutthroat, and German brown trout.[89] The greenback cutthroat, once widespread in Eastern Colorado, is currently listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act.

During the winter most of Trail Ridge Road is closed due to heavy snow, limiting motorized access to the edges of the park.[67] Winter activities include snowshoeing and cross-country skiing which are possible from either the Estes Park or Grand Lake entrances. On the east side near Estes Park, skiing and snowshoeing trails are available off Bear Lake Road, such as the Bear Lake, Bierstadt Lake, and Sprague Lake trails and at Hidden Valley. Slopes for sledding are also available at Hidden Valley. The west side of the park near Grand Lake also has viable snowshoeing trails.[67][94] Backcountry skiing and snowboarding can be enjoyed after climbing up one of the higher slopes, especially late in the snow season after avalanche danger has subsided[95] and technical climbing remains also a possibility, although typically differing in style from the summer months.[96]

Hazards

Encountering bears is a concern in much of the Rocky Mountains, including the Wind River Range.[97] There are other concerns as well, including bugs, wildfires, adverse snow conditions and nighttime cold temperatures.[98]

There have been notable incidents, including accidental deaths, due to falls from steep cliffs (a misstep could be fatal in this class 4/5 terrain) and due to falling rocks, over the years, including 1993,[99] 2007 (involving an experienced NOLS leader),[100] 2015[101] and 2018.[102] Other incidents include a seriously injured backpacker being airlifted near SquareTop Mountain[103] in 2005,[104] and a fatal hiker incident (from an apparent accidental fall) in 2006 that involved state search and rescue.[105] According to data from the National Park Service,[106] there have been 77 fatalities at the park between 2007 and 2024, the majority of which were from accidental falls while hiking or climbing.[107]

Wildfires

Wildfires have been recorded in Rocky Mountain National Park prior to its establishment in 1915. Some of the most notable wildfires include the Bear Lake Fire, which was started by a campfire that was failed to be properly put out, and burned for two months in 1900. The Ouzel Fire in 1978 was caused naturally by lightning and was allowed to burn under supervision until it grew out of control and in total burned 1,050 acres of land. The Fern Lake Fire in 2012 was also caused by a campfire, the fire was intensified due to strong winds and drought in the area. Absence of fire in around Fern Lake for many centuries caused excessive dead trees and a thick layer of organic matter on the ground which fuelled the fire, ultimately leading to the it lasting for over two months, burning nearly 3,500 acres of land.[108]

An increase in average temperature in the Rocky Mountain region has been correlated to a decrease in snowfall that melts earlier in the year, attributing to drier summers and longer fire seasons. Rocky Mountain National Park is expected to see one of the largest increases in number of wildfires for the United States, with an increase in both duration and intensity for wildfires in general across the nation.[109][110]

Wildfires that have a higher burn severity can cause serious damage to an ecosystem. High-severity wildfires can cause soil degradation by affecting the soils’ ability to absorb and process water. They also cause an increase in erosion due to burning away vegetation that holds the soil to the ground, thus increasing the chances of flooding and mudslides that cause further damage in and around the affected areas. Ash from the fires also contributes significantly to air and water pollution.[111][112]

Low-severity wildfires however are crucial to maintaining a balanced ecosystem and can help prevent the damaging high-severity wildfires by clearing away excess organic material that adds fuel to and amplifies the spread of more severe wildfires. While severe fires can negatively impact the soil, less severe wildfires can be beneficial as burning the nutrient-rich dead organic material helps to fertilize the soil. The smaller fires also clear room for new growth and can fight against invasive species encroachment in the park.[110][113]

Many parks including Rocky Mountain National Park use small fires as means to prevent more severe fires from getting out of hand. Along with small, prescribed burns, other fuel management practices include removing low hanging branches and forest thinning in general. Scientists have been working hard to find a balance in wildfires, allowing them to work as a restorative ecological process while avoiding the damage and pollution that come with high-severity wildfires.[110]

Access

The park may be accessed through Estes Park or via the western entrance at Grand Lake. Trail Ridge Road, also known as U.S. Route 34, connects the eastern and western sides of the park.[114] The park has five visitor centers. The Alpine Visitor Center is located in the tundra environment along Trail Ridge Road, while Beaver Meadows and Fall River are both near Estes Park, with Kawuneeche in the Grand Lake area, and the Moraine Park Discovery Center near the Beaver Meadows entrance and visitor center.[11]

Trail Ridge Road and other roads

Trail Ridge Road is 48 miles (77 km) long and connects the entrances in Grand Lake and Estes Park.[115][116] Running generally east–west through many hairpin turns,[6] the road crosses Milner Pass through the Continental Divide[116] at an elevation of 10,758 ft (3,279 m).[115][117] The highest point of the road is 12,183 feet (3,713 m),[116] with eleven miles of the road being above tree line which is approximately 11,500 feet (3,505 m).[115] The road is the highest continuously paved highway in the country,[116] and includes many large turnouts at key points to stop and observe the scenery.[115]

Most visitors to the park drive over the famous Trail Ridge Road, but other roads include Fall River Road and Bear Lake Road.[118] The park is open every day of the year, weather permitting.[119] Due to the extended winter season in higher elevations, Trail Ridge Road between Many Parks Curve and the Colorado River Trailhead is closed much of the year. The road is usually open again by Memorial Day and closes in mid-October, generally after Columbus Day.[116] Fall River Road does not open until about July 4 and closes by, or in, October for vehicular traffic.[120] Snow may also fall in sufficient quantities in higher elevations to require temporary closure of the roads into July,[51][116] which is reported on the road status site.[118]

Estes Park

Most visitors enter the park through the eastern entrances near Estes Park, which is about 71 miles (114 km) northwest of Denver.[114] The most direct route to Trail Ridge Road is the Beaver Meadows entrance, located just west of Estes Park on U.S. Route 36, which leads to the Beaver Meadows Visitor Center and the park's headquarters. North of the Beaver Meadows entrance station is the Fall River entrance, which also leads to Trail Ridge Road and Old Fall River Road.[114] There are three routes into Estes Park: I-25 to U.S. 34 west which runs alongside the Big Thompson River; U.S. 36 west (northwest) from Boulder connecting to U.S. 34 west; and the Peak to Peak Highway, also known as State Highway 7, from points south.[114]

The nearest airport is Denver International Airport[114] and the closest train station is the Denver Union Station. Estes Park may be reached by rental car or shuttle.[114][121] During peak tourist season, there is free shuttle service within the park; additionally, the town of Estes Park provides shuttle service to Estes Park Visitor Center, surrounding campgrounds, and the Rocky Mountain National Park's shuttles.[114]

Grand Lake

Visitors may also enter at the western side of the park from U.S. 34 near Grand Lake. U.S. 34 is reached by taking U.S. 40 north from I-70.[114] The closest railroad station is the Amtrak station in Granby, which is 20 miles (32 km) from the western entrance of the park. Taxi service is available into the park.[121]

See also

- List of national parks of the United States

- List of areas in the United States National Park System – parks, monuments, preserves, historic sites, etc.

- Birds of Rocky Mountain National Park

- Southern Rocky Mountain Front - where the Rocky Mountains meet the plains

Notes

- ^ Montana State University states in their profile of Rocky Mountain National Park that there has been an increase of 2.5 °F (1.4 °C) in the average park temperature over "the past century" (charts show the period from about 1895 to 2010).[50] The National Park Service site states that the increase has been 3.4 °F (1.9 °C) over "the last century" (chart shows the period from about 1905-2010).[55]

References

- ^ Rocky Mountain in United States of America Archived 2019-07-24 at the Wayback Machine. protectedplanet.net. United Nations Environment World Conservation Monitoring Centre and the IUCN's World Commission on Protected Areas. Retrieved July 25, 2019.

- ^ a b "The National Parks: Index 2009-2011" (PDF). nps.gov. National Park Service. p. 33. Retrieved February 3, 2017.

- ^ a b c d "Brief Park History". nps.gov. National Park Service. n.d. Archived from the original on October 8, 2016. Retrieved December 4, 2016.

- ^ "Annual Park Ranking Report for Recreation Visits in: 2022". nps.gov. National Park Service.

- ^ "Rocky Mountain National Park Mileages and Elevations". nps.gov. National Park Service. n.d. Archived from the original on October 8, 2016. Retrieved November 29, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Rocky Mountain National Park Maps". nps.gov. National Park Service. n.d. Archived from the original on October 8, 2016. Retrieved November 2, 2016.

- ^ "Biosphere Reserve Information, United States of America, Rocky Mountain". unesco.org. UNESCO. August 17, 2000. Archived from the original on August 24, 2015. Retrieved November 29, 2016.

- ^ "Top 10 most visited national parks". Travel. March 27, 2024. Retrieved March 27, 2024.

- ^ "These Were the Most Visited National Parks in 2015". Time Magazine. February 17, 2016. Archived from the original on February 18, 2016. Retrieved February 9, 2018.

- ^ Meyer, John (February 14, 2019). "Rocky Mountain National Park sets another attendance record with 4.6 million visitors in 2019". The Denver Post. Retrieved February 14, 2019.

- ^ a b "Rocky Mountain National Park Visitor Centers". National Park Service. n.d. Retrieved November 1, 2016.

- ^ "Beaver Meadows Visitor Center Review | Rocky Mountain NP | Fodor's Travel Guides". Fodors.com. Retrieved June 4, 2013.

- ^ Perry 2008, p. 9; Buchholtz 1983, p. 20.

- ^ Buchholtz 1983, p. 8; Law 2015, pp. 53–54.

- ^ a b Law 2015, p. 76.

- ^ Buckley & Nokes 2016, p. 131.

- ^ U.S. Corps of Topographical Engineers.

- ^ Buchholtz 1983, p. 42.

- ^ Law 2015, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Perry 2008, p. 18.

- ^ Perry 2008, pp. 50.

- ^ Cammerer, Arno B. (1934). Rocky Mountain National Park. Washington DC: United States Government Printing Office.

- ^ "History of Trail Ridge Road". nps.gov. National Park Service. Retrieved March 22, 2017.

- ^ Frank 2013, pp. 7–8; Buchholtz 1983, p. 135.

- ^ "National Forest Ranger Districts". Rocky Mountain National Park. Archived from the original on June 21, 2017. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

- ^ a b c "Rocky Mountain National Park". Backpacker Magazine. September 20, 2013. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

- ^ Kim Lipker (February 9, 2016). Day and Overnight Hikes: Rocky Mountain National Park. Menasha Ridge Press, Incorporated. p. PT19. ISBN 978-1-63404-016-7.

- ^ "Where Locals Hike in Rocky Mountain National Park". My Rocky Mountain Park. National Park Trips Media. Archived from the original on June 6, 2017. Retrieved November 6, 2016.

- ^ a b c "National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline data". U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved May 7, 2017.

- ^ "About Rocky Mountain National Park". Rocky Mountain Hiking Trails. Retrieved October 30, 2016.

- ^ a b c "Rocky Mountain National Park: Natural Features and Ecosystems". National Park Service. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

- ^ "LONGS PEAK". NGS Data Sheet. National Geodetic Survey, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, United States Department of Commerce. Retrieved February 3, 2017.

- ^ "Trail Ridge Road: Rocky Mountain National Park". codot.gov. Colorado Department of Transportation. Archived from the original on November 17, 2018. Retrieved February 22, 2018.

- ^

This article incorporates public domain material from "Mummy Range - Decision Card". U.S. Geological Survey - Geological Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

This article incorporates public domain material from "Mummy Range - Decision Card". U.S. Geological Survey - Geological Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

- ^ a b

This article incorporates public domain material from Glaciers of Rocky Mountain National Park. National Park Service. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

This article incorporates public domain material from Glaciers of Rocky Mountain National Park. National Park Service. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e

This article incorporates public domain material from "Rocky Mountain National Park Trails and Trailheads by Region". Rocky Mountain National Park. National Park Service. Retrieved October 30, 2016.

This article incorporates public domain material from "Rocky Mountain National Park Trails and Trailheads by Region". Rocky Mountain National Park. National Park Service. Retrieved October 30, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e

This article incorporates public domain material from "Hiking trails on the west side of Rocky Mountain National Park". Rocky Mountain National Park. National Park Service. Retrieved October 30, 2016.

This article incorporates public domain material from "Hiking trails on the west side of Rocky Mountain National Park". Rocky Mountain National Park. National Park Service. Retrieved October 30, 2016.

- ^ "Rocky Mountain National Park History - Mining" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved November 6, 2016.

- ^ McWilliams, Carl and Karen (August 20, 1985). "National Register of Historic Places - Classified Structure Field Inventory Report". nps.gov. National Park Service. pp. 10–11. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ^ Lisa Foster (2005). Rocky Mountain National Park: The Complete Hiking Guide. Big Earth Publishing. p. 284. ISBN 978-1-56579-550-1.

- ^ a b "Alpine Trails". Rocky Mountain National Park. Archived from the original on May 29, 2021. Retrieved November 6, 2016.

- ^ Brachfeld, Aaron (September 2015). "Trail to Bridal Veil Falls, Rocky Mountain National Park". the Meadowlark Herald. No. September 2015. the Meadowlark Herald. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Hiking trails on the north side of Rocky Mountain National Park". Rocky Mountain National Park. Archived from the original on April 29, 2021. Retrieved November 6, 2016.

- ^ "Gem Lake, Balanced Rock, & Paul Bunyan's Boot". Archived from the original on June 23, 2017. Retrieved February 5, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Trails in the Heart of the Rocky Mountain National Park". Rocky Mountain National Park. Retrieved November 7, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Lisa Foster (2005). Rocky Mountain National Park: The Complete Hiking Guide. Big Earth Publishing. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-56579-550-1.

- ^ Lisa Foster (2005). Rocky Mountain National Park: The Complete Hiking Guide. Big Earth Publishing. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-56579-550-1.

- ^ a b c d "Trails in the Wild Basin and Longs Peak of the Rocky Mountain National Park". Rocky Mountain National Park. Archived from the original on April 27, 2021. Retrieved November 7, 2016.

- ^ "USDA Interactive Plant Hardiness Map". United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved July 16, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Rocky Mountain National Park Climate Primer" (PDF). Montana State University. p. 1. Retrieved November 2, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k

This article incorporates public domain material from "Rocky Mountain National Park - Weather". NPS. National Park Service. Retrieved November 2, 2016.

This article incorporates public domain material from "Rocky Mountain National Park - Weather". NPS. National Park Service. Retrieved November 2, 2016.

- ^ a b "PRISM Climate Group, Oregon State University". www.prism.oregonstate.edu. Retrieved July 16, 2019.

- ^ a b "Landscape Climate Change Vulnerability Project; Using NASA Resources to Inform Climate and Land Use Adaptation; Ecological Forecasting, Vulnerability Assessment, and Evaluation of Management Options Across Two US DOI Landscape Conservation Cooperatives" (PDF). montana.edu. Montana State University. August 2011. pp. 2, 5. Retrieved February 5, 2017.

- ^ "Landscape Climate Change Vulnerability Project". montana.edu. Montana State University. Retrieved November 2, 2016.

- ^ a b

This article incorporates public domain material from "Climate Change". National Park Service. National Park Service. Retrieved November 3, 2016.

This article incorporates public domain material from "Climate Change". National Park Service. National Park Service. Retrieved November 3, 2016.

- ^ a b "Rocky Mountain National Park Climate Primer" (PDF). Montana State University. p. 3. Retrieved November 2, 2016.

- ^ Gadd, Ben (1995). Handbook of the Canadian Rockies. Corax Press. p. 76. ISBN 9780969263111.

- ^ a b c d e f g Kirk R. Johnson; Robert G. Raynolds (2006). Ancient Denvers: Scenes from the Past 300 Million Years of the Colorado Front Range. Fulcrum Publishing for Denver Museum of Nature and Science. ISBN 1-55591-554-X.

- ^ a b c "Teacher Guide to RMNP Geology" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved October 30, 2016.

- ^ "Rocky Mountain National Park - Geologic History". National Park Service. Retrieved October 30, 2016.

- ^

This article incorporates public domain material from "Glaciers". Rocky Mountain National Park. National Park Service. Retrieved November 2, 2016.

This article incorporates public domain material from "Glaciers". Rocky Mountain National Park. National Park Service. Retrieved November 2, 2016.

- ^ "U.S. Potential Natural Vegetation, Original Kuchler Types, v2.0 (Spatially Adjusted to Correct Geometric Distortions)". Data Basin. Retrieved July 16, 2019.

- ^ Fraces Alley Kelly; Carron A. Meaney (1995). Explore Colorado: A Naturalist's Notebok. Photography by John Fielder. Englewood, Colorado: Westcliff Publishers and Denver Museum of Natural History. pp. 10–13. ISBN 1-56579-124-X.

- ^

This article incorporates public domain material from "Majestic view from the old, one-way, dirt Fall River Road in Rocky Mountain National Park in the Front Range of the spectacular and high Rockies in north-central Colorado". Library of Congress - Prints & Photographs Online Catalog. Library of Congress. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

This article incorporates public domain material from "Majestic view from the old, one-way, dirt Fall River Road in Rocky Mountain National Park in the Front Range of the spectacular and high Rockies in north-central Colorado". Library of Congress - Prints & Photographs Online Catalog. Library of Congress. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

- ^ "Ecosystems of Rocky Teacher Guide" (PDF). Rocky Mountain National Park. p. 4. Retrieved November 3, 2016.

- ^ a b c "Rocky Mountain National Park". UNESCO. Retrieved November 10, 2016.

- ^ a b c Claire Walter (2004). Snowshoeing Colorado. Fulcrum Publishing. pp. 51–52. ISBN 978-1-55591-529-2.

- ^ Russell, Piper (March 27, 2024). "One of country's 'most polluted' national parks is located in Colorado". OutThere Colorado. Retrieved March 30, 2024.

According to the "Polluted Parks" report from the National Parks Conservation Association (NPCA), 97% of national parks suffer from significant or unsatisfactory levels of air pollution… NPCA listed Rocky Mountain National Park (RMNP) as the ninth most-polluted U.S. national park, specifically looking at parks with 'unhealthy air.'… According to the National Park Service, vehicles, power plants, agriculture, fire, oil, gas, and more contribute to air pollution in RMNP. NPCA also reports that the boom in oil and gas production in Weld County has adversely affected RMNP, causing the park to fall out of compliance with the Clean Air Act.

- ^ Kieckhefer, Ben (February 22, 2004). "Rocky Mountain Park Is Having Bad Air Days". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 30, 2024.

- ^ Politics, Alayna Alvarez; Colorado (April 15, 2021). "The Brown Cloud: Denver air quality concerns date back to 1800s". OutThere Colorado. Retrieved March 30, 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c

This article incorporates public domain material from "Nature and Ecosystems". Rocky Mountain National Park. National Park Service. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

This article incorporates public domain material from "Nature and Ecosystems". Rocky Mountain National Park. National Park Service. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e

This article incorporates public domain material from "Montane Ecosystem". Rocky Mountain National Park. National Park Service. Retrieved November 1, 2016.

This article incorporates public domain material from "Montane Ecosystem". Rocky Mountain National Park. National Park Service. Retrieved November 1, 2016.

- ^ "Watching Wildlife - Horseshoe Park". Rocky Mountain National Park. Archived from the original on April 28, 2021. Retrieved November 1, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e

This article incorporates public domain material from "Subalpine Ecosystem". Rocky Mountain National Park. National Park Service. Retrieved November 1, 2016.

This article incorporates public domain material from "Subalpine Ecosystem". Rocky Mountain National Park. National Park Service. Retrieved November 1, 2016.

- ^ a b c d

This article incorporates public domain material from "Alpine Tundra Ecosystem". Rocky Mountain National Park. National Park Service. Retrieved November 1, 2016.

This article incorporates public domain material from "Alpine Tundra Ecosystem". Rocky Mountain National Park. National Park Service. Retrieved November 1, 2016.

- ^ "Ecosystems of Rocky Teacher Guide" (PDF). Rocky Mountain National Park. p. 9. Retrieved November 3, 2016.

- ^ "Ecosystems of Rocky Teacher Guide" (PDF). Rocky Mountain National Park. p. 17. Retrieved November 3, 2016.

- ^

This article incorporates public domain material from Mammals - Rocky Mountain National Park. National Park Service. September 26, 2023. Retrieved November 1, 2023.

This article incorporates public domain material from Mammals - Rocky Mountain National Park. National Park Service. September 26, 2023. Retrieved November 1, 2023.

- ^ Blumhardt, Miles (November 23, 2022). "Wolves were once an option to reduce Rocky Mountain National Park's popular elk herd". Fort Collins Coloradoan. Retrieved November 23, 2022.

- ^ "Elk - Rocky Mountain National Park". National Park Service.

- ^ "Moose - Rocky Mountain National Park". National Park Service.

- ^ "Bighorn Sheep - Rocky Mountain National Park". National Park Service.

- ^ "Black Bears - Rocky Mountain National Park". National Park Service.

- ^ "Mountain Lions - Rocky Mountain National Park". National Park Service.

- ^ "Coyote - Rocky Mountain National Park". National Park Service.

- ^ "Wilderness Designated Site Details". Rocky Mountain National Park. National Park Service. Retrieved November 29, 2021.

- ^ "Continental Divide Loop – Rocky Mountain National Park (45 mile loop)". Backpackers-review.com. July 7, 2017. Retrieved November 29, 2021.

- ^ Lisa Foster (2005). Rocky Mountain National Park: The Complete Hiking Guide. Big Earth Publishing. pp. 17–18. ISBN 978-1-56579-550-1.

- ^ a b Lisa Gollin-Evans (June 3, 2011). Outdoor Family Guide to Rocky Mountain National Park, 3rd Edition. The Mountaineers Books. p. 62. ISBN 978-1-59485-499-6.

- ^ "Horse and Pack Animals - Rocky Mountain National Park" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved November 10, 2016.

- ^ Lisa Gollin-Evans (June 3, 2011). Outdoor Family Guide to Rocky Mountain National Park, 3rd Edition. The Mountaineers Books. pp. 63–64. ISBN 978-1-59485-499-6.

- ^ "RMNP - Rock Climbing". Mountain Project. Retrieved February 7, 2019.

- ^ "Boulderers' perceptions of Leave No Trace in Rocky Mountain National Park" (PDF). November 2016.

- ^ Andy Lightbody; Kathy Mattoon (December 3, 2013). Winter TrailsTM Colorado: The Best Cross-Country Ski and Snowshoe Trails. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 26–32. ISBN 978-1-4930-0716-5.

- ^ Alan Apt; Kay Turnbaugh (July 7, 2015). Afoot and Afield: Denver, Boulder, Fort Collins, and Rocky Mountain National Park: 184 Spectacular Outings in the Colorado Rockies. Wilderness Press. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-89997-755-3.

- ^ "RMNP Mixed/Ice climbing". Mountain Project. Retrieved February 7, 2019.

- ^ Staff (April 24, 2017). "Bear Safety in Wyoming's Wind River Country". WindRiver.org. Archived from the original on July 26, 2021. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ^ Ballou, Dawn (July 27, 2005). "Wind River Range condition update – Fires, trails, bears, Continental Divide". PineDaleOnline News. Archived from the original on April 21, 2021. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ^ Staff (1993). "Falling Rock, Loose Rock, Failure to Test Holds, Wyoming, Wind River Range, Seneca Lake". American Alpine Club. Archived from the original on July 26, 2021. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ^ MacDonald, Dougald (August 14, 2007). "Trundled Rock Kills NOLS Leader". Climbing. Archived from the original on July 26, 2021. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ^ Staff (December 9, 2015). "Officials rule Wind River Range climbing deaths accidental". Casper Star-Tribune. Archived from the original on July 26, 2021. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ^ Dayton, Kelsey (August 24, 2018). "Deadly underestimation". WyoFile News. Archived from the original on July 26, 2021. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ^ Funk, Jason (2009). "Squaretop Mountain Rock Climbing". Mountain Project. Archived from the original on July 26, 2021. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ^ Staff (July 22, 2005). "Injured man rescued from Square Top Mtn – Tip-Top Search & Rescue helps 2 injured on the mountain". PineDaleOnline News. Archived from the original on July 26, 2021. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ^ Staff (September 1, 2006). "Incident Reports – September, 2006 – Wind River Search". WildernessDoc.com. Archived from the original on January 27, 2020. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ^ "Deaths in National Parks (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved December 4, 2024.

- ^ Team, Legal (October 24, 2024). "Rocky Mountain National Park Deaths | Updated 2024". Dulin McQuinn Young. Retrieved December 4, 2024.

- ^ Park, Mailing Address: 1000 US Hwy 36 Estes; Fridays, CO 80517 Phone: 970 586-1206 The Information Office is open year-round: 8:00 a m- 4:00 p m daily in summer; 8:00 a m- 4:00 p m Mondays-; Us, 8:00 a m-12:00 p m Saturdays- Sundays in winter Recorded Trail Ridge Road status:586-1222 Contact. "Fire History - Rocky Mountain National Park (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved April 25, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Fire". National Parks Conservation Association. Retrieved April 25, 2022.

- ^ a b c Park, Mailing Address: 1000 US Hwy 36 Estes; Fridays, CO 80517 Phone: 970 586-1206 The Information Office is open year-round: 8:00 a m- 4:00 p m daily in summer; 8:00 a m- 4:00 p m Mondays-; Us, 8:00 a m-12:00 p m Saturdays- Sundays in winter Recorded Trail Ridge Road status:586-1222 Contact. "After Fires, Rocky Mountain National Park Assesses Impacts Looks to the Future - Rocky Mountain National Park (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved April 25, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Restoration & Rehabilitation". Colorado State Forest Service. Retrieved April 25, 2022.

- ^ "Wildfires | CDC". www.cdc.gov. December 21, 2020. Retrieved April 25, 2022.

- ^ Society, National Geographic (January 15, 2020). "The Ecological Benefits of Fire". National Geographic Society. Retrieved April 25, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Rocky Mountain National Park - Getting There". Frommers. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

- ^ a b c d "Trail Ridge Road". nps.gov. National Park Service. Retrieved February 5, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f "Trail Ridge Road". Rocky Mountain National Park. Archived from the original on April 28, 2021. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

- ^ "Milner Pass". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved February 5, 2017.

- ^ a b

This article incorporates public domain material from "Road Status". Rocky Mountain National Park. National Park Service. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

This article incorporates public domain material from "Road Status". Rocky Mountain National Park. National Park Service. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

- ^

This article incorporates public domain material from "Getting Around". Rocky Mountain National Park. National Park Service. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

This article incorporates public domain material from "Getting Around". Rocky Mountain National Park. National Park Service. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

- ^

This article incorporates public domain material from "Old Fall River Road". Rocky Mountain National Park. National Park Service. Retrieved November 2, 2016.

This article incorporates public domain material from "Old Fall River Road". Rocky Mountain National Park. National Park Service. Retrieved November 2, 2016.

- ^ a b "Ride a Train, Bus or Taxi to Rocky Mountain National Park". National Park Trips Media. Archived from the original on June 7, 2017. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

Sources

- Buchholtz, C. W. (1983). Rocky Mountain National Park: A History. University Press of Colorado. ISBN 0-87081-146-0.

- Buckley, Jay H.; Nokes, Jeffery D. (March 28, 2016). Explorers of the American West: Mapping the World through Primary Documents. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-61069-732-3.

- Frank, Jerry J. (2013). Making Rocky Mountain National Park: The Environmental History of an American Treasure.

- Law, Amy (March 16, 2015). Natural History of Trail Ridge Road: A Rocky Mountain National Park's Highway to the Sky. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-1-62619-935-4.

- Perry, Phyllis J. (2008). Rocky Mountain National Park. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-5627-7.

- U.S. Corps of Topographical Engineers. "Stephen Harriman Long, Topographical Engineers". U.S. Corps of Topographical Engineers. Archived from the original on December 4, 2010. Retrieved March 21, 2010.

Further reading

- Andrews, Thomas G. (2015). Coyote Valley: Deep History in the High Rockies. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674088573.

- Cole, James C.; Braddock, William A. (2009). Geologic Map of the Estes Park 30' x 60' Quadrangle, North-Central Colorado. Scientific Investigations Map 3039. U.S. Geological Survey. ISBN 978-1-4113-2221-9. This source discusses the geology of the quadrangle, which covers most of Rocky Mountain National Park.

- Emerick, John C. (1995). Rocky Mountain National Park Natural History Handbook. Roberts Hinehart Publishers/Rocky Mountain Nature Association. ISBN 1-879373-80-7.

- Mills, Enos and John Fielder. Rocky Mountain National Park: A 100 Year Perspective (1995)

- Musselman, Lloyd K. (July 1971). Rocky Mountain National Park: Administrative History, 1915-1965 (Online ed.). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Dept. of the Interior, National Park Service, Office of History and Historic Architecture, Eastern Service Center. Retrieved November 18, 2014.

- U.S. Dept. of the Interior. Rocky Mountain [Colorado] National Park (2011) online free

External links

- Official website

of the National Park Service

of the National Park Service - Rocky Mountain National Park map

- Rocky Mountain Conservancy (formerly the Rocky Mountain Nature Association)

- Virtual ride over Trail Ridge Road

- Plant Checklist (with photographs) for the Rocky Mountain National Park

- Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) documentation, filed under Estes Park, Larimer County, CO:

- HAER No. CO-31, "Trail Ridge Road, Between Estes Park and Grand Lake", 21 photos, 1 color transparency, 69 data pages, 2 photo caption pages

- HAER No. CO-73, "Fall River Road, Between Estes Park and Fall River Pass", 14 photos, 1 color transparency, 40 data pages, 2 photo caption pages

- HAER No. CO-78, "Rocky Mountain National Park Roads", 8 measured drawings, 86 data pages