Robert Schumann

Robert Schumann | |

|---|---|

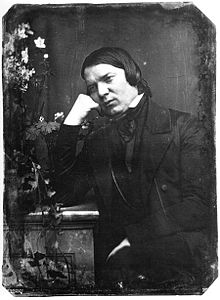

Schumann in 1839 | |

| Born | 8 June 1810 Zwickau, Kingdom of Saxony |

| Died | 29 July 1856 (aged 46) Bonn, Rhine Province, Prussia |

| Occupations |

|

| Spouse | |

Robert Schumann[n 1] (German: [ˈʁoːbɛʁt ˈʃuːman]; 8 June 1810 – 29 July 1856) was a German composer, pianist, and music critic of the early Romantic era. He composed in all the main musical genres of the time, writing for solo piano, voice and piano, chamber groups, orchestra, choir and the opera. His works typify the spirit of the Romantic era in German music.

Schumann was born in Zwickau, Saxony, to an affluent middle-class family with no musical connections, and was initially unsure whether to pursue a career as a lawyer or to make a living as a pianist-composer. He studied law at the universities of Leipzig and Heidelberg but his main interests were music and Romantic literature. From 1829 he was a student of the piano teacher Friedrich Wieck, but his hopes for a career as a virtuoso pianist were frustrated by a worsening problem with his right hand, and he concentrated on composition. His early works were mainly piano pieces, including the large-scale Carnaval, Davidsbündlertänze (Dances of the League of David), Fantasiestücke (Fantasy Pieces), Kreisleriana and Kinderszenen (Scenes from Childhood) (1834–1838). He was a co-founder of the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik (New Musical Journal) in 1834 and edited it for ten years. In his writing for the journal and in his music he distinguished between two contrasting aspects of his personality, dubbing these alter egos "Florestan" for his impetuous self and "Eusebius" for his gentle poetic side.

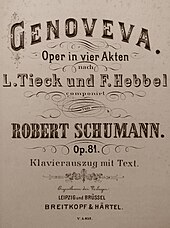

Despite the bitter opposition of Wieck, who did not regard his pupil as a suitable husband for his daughter, Schumann married Clara in 1840. In the years immediately following their wedding Schumann composed prolifically, writing, first, songs and song‐cycles including Frauenliebe und Leben ("Woman's Love and Life") and Dichterliebe ("Poet's Love"). He turned his attention to orchestral music in 1841, completing the first of his four symphonies. In the following year he concentrated on chamber music, writing three string quartets, a Piano Quintet and a Piano Quartet. During the rest of the 1840s, between bouts of mental and physical ill health, he composed a variety of piano and other pieces and went with his wife on concert tours in Europe. His only opera, Genoveva (1850), was not a success and has seldom been staged since.

Schumann and his family moved to Düsseldorf in 1850 in the hope that his appointment as the city's director of music would provide financial security, but his shyness and mental instability made it difficult for him to work with his orchestra and he had to resign after three years. In 1853 the Schumanns met the twenty-year-old Johannes Brahms, whom Schumann praised in an article in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik. The following year Schumann's always-precarious mental health deteriorated gravely. He threw himself into the River Rhine but was rescued and taken to a private sanatorium near Bonn, where he lived for more than two years, dying there at the age of 46.

During his lifetime Schumann was recognised for his piano music – often subtly programmatic – and his songs. His other works were less generally admired, and for many years there was a widespread belief that those from his later years lacked the inspiration of his early music. More recently this view has been less prevalent, but it is still his piano works and songs from the 1830s and 1840s on which his reputation is primarily based. He had considerable influence in the nineteenth century and beyond. In the German-speaking world the composers Gustav Mahler, Richard Strauss, Arnold Schoenberg and more recently Wolfgang Rihm have been inspired by his music, as were French composers such as Georges Bizet, Gabriel Fauré, Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel. Schumann was also a major influence on the Russian school of composers, including Anton Rubinstein and Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky.

Life and career

Childhood

Robert Schumann[n 1] was born in Zwickau, in the Kingdom of Saxony (today the German state of Saxony), into an affluent middle-class family.[4] On 13 June 1810 the local newspaper, the Zwickauer Wochenblatt (Zwickau Weekly Paper), carried the announcement, "On 8 June to Herr August Schumann, notable citizen and bookseller here, a little son".[5] He was the fifth and last child of August Schumann and his wife, Johanna Christiane (née Schnabel). August, not only a bookseller but also a lexicographer, author and publisher of chivalric romances, made considerable sums from his German translations of writers such as Cervantes, Walter Scott and Lord Byron.[2] Robert, his favourite child, was able to spend many hours exploring the classics of literature in his father's collection.[2] Intermittently, between the ages of three and five-and-a-half, he was placed with foster parents, as his mother had contracted typhus.[4]

At the age of six Schumann went to a private preparatory school, where he remained for four years.[6] When he was seven he began studying general music and piano with the local organist, Johann Gottfried Kuntsch, and for a time he also had cello and flute lessons with one of the municipal musicians, Carl Gottlieb Meissner.[7] Throughout his childhood and youth his love of music and literature ran in tandem, with poems and dramatic works produced alongside small-scale compositions, mainly piano pieces and songs.[8] He was not a musical child prodigy like Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart or Felix Mendelssohn,[4] but his talent as a pianist was evident from an early age: in 1850 the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung (Universal Musical Journal) printed a biographical sketch of Schumann which included an account from contemporary sources that even as a boy he possessed a special talent for portraying feelings and characteristic traits in melody:

From 1820 Schumann attended the Zwickau Lyceum, the local high school of about two hundred boys, where he remained till the age of eighteen, studying a traditional curriculum. In addition to his studies he read extensively: among his early enthusiasms were Schiller and Jean Paul.[10] According to the musical historian George Hall, Paul remained Schumann's favourite author and exercised a powerful influence on the composer's creativity with his sensibility and vein of fantasy.[8] Musically, Schumann got to know the works of Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, and of living composers Carl Maria von Weber, with whom August Schumann tried unsuccessfully to arrange for Robert to study.[8] August was not particularly musical but he encouraged his son's interest in music, buying him a Streicher grand piano and organising trips to Leipzig for a performance of Die Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute) and Carlsbad to hear the celebrated pianist Ignaz Moscheles.[11]

University

August Schumann died in 1826; his widow was less enthusiastic about a musical career for her son and persuaded him to study for the law as a profession. After his final examinations at the Lyceum in March 1828 he entered Leipzig University. Accounts differ about his diligence as a law student. According to his roommate Emil Flechsig, he never set foot in a lecture hall,[13] but he himself recorded, "I am industrious and regular, and enjoy my jurisprudence ... and am only now beginning to appreciate its true worth".[14] Nonetheless reading and playing the piano occupied a good deal of his time, and he developed expensive tastes for champagne and cigars.[8] Musically, he discovered the works of Franz Schubert, whose death in November 1828 caused Schumann to cry all night.[8] The leading piano teacher in Leipzig was Friedrich Wieck, who recognised Schumann's talent and accepted him as a pupil.[15]

After a year in Leipzig Schumann convinced his mother that he should move to the University of Heidelberg which, unlike Leipzig, offered courses in Roman, ecclesiastical and international law (as well as reuniting Schumann with his close friend Eduard Röller who was a student there).[16] After matriculating at the university on 30 July 1829 he travelled in Switzerland and Italy from late August to late October. He was greatly taken with Rossini's operas and the bel canto of the soprano Giuditta Pasta; he wrote to Wieck, "one can have no notion of Italian music without hearing it under Italian skies".[13] Another influence on him was hearing the violin virtuoso Niccolò Paganini play in Frankfurt in April 1830.[17] In the words of one biographer, "The easy-going discipline at Heidelberg University helped the world to lose a bad lawyer and to gain a great musician".[18] Finally deciding in favour of music rather than the law as a career, he wrote to his mother on 30 July 1830 telling her how he saw his future: "My entire life has been a twenty-year struggle between poetry and prose, or call it music and law".[19] He persuaded her to ask Wieck for an objective assessment of his musical potential. Wieck's verdict was that with the necessary hard work Schumann could become a leading pianist within three years. A six-month trial period was agreed.[20]

1830s

Later in 1830 Schumann published his Op. 1, a set of piano variations on a theme based on the name of its supposed dedicatee, Countess Pauline von Abegg (who was almost certainly a product of Schumann's imagination).[21] The notes A-B♭-E-G-G (A-B-E-G-G in German nomenclature, which uses "B" for the note known elsewhere as B♭ and "H" for the note known elsewhere as B[♮]), played in waltz tempo, make up the theme on which the variations are based.[22] The use of a musical cryptogram became a recurrent characteristic of Schumann's later music.[8] In 1831 he began lessons in harmony and counterpoint with Heinrich Dorn, musical director of the Saxon court theatre,[23] and in 1832 he published his Op. 2, Papillons (Butterflies) for piano, a programmatic piece depicting twin brothers – one a poetic dreamer, the other a worldly realist – both in love with the same woman at a masked ball.[24] Schumann had by now come to regard himself as having two distinct sides to his personality and art: he dubbed his introspective, pensive self "Eusebius" and the impetuous and dynamic alter ego "Florestan".[25][n 2] Reviewing an early work of Chopin in 1831 he wrote:

Schumann's pianistic ambitions were ended by a growing paralysis in at least one finger of his right hand. The early symptoms had come while he was still a student at Heidelberg, and the cause is uncertain.[29][n 3] He tried all the treatments then in vogue including allopathy, homeopathy, and electric therapy, but without success.[31] The condition had the advantage of exempting him from compulsory military service – he could not fire a rifle[31] – but by 1832 he recognised that a career as a virtuoso pianist was impossible and he shifted his main focus to composition. He completed further sets of small piano pieces and the first movement of a symphony (it was too thinly orchestrated according to Wieck and was never completed).[32] An additional activity was journalism. From March 1834, along with Wieck and others, he was on the editorial board of a new music magazine, Neue Leipziger Zeitschrift für Musik (New Leipzig Music Magazine), which was reconstituted under his sole editorship in January 1835 as the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik.[33] Hall writes that it took "a thoughtful and progressive line on the new music of the day".[34] Among the contributors were friends and colleagues of Schumann, writing under pen names: he included them in his Davidsbündler (League of David) – a band of fighters for musical truth, named after the Biblical hero who fought against the Philistines – a product of the composer's imagination in which, blurring the boundaries of imagination and reality, he included his musical friends.[34]

During successive months in 1835 Schumann met three musicians whom he regarded with particular respect: Felix Mendelssohn, Chopin and Moscheles.[35] Of these, he was most influenced in his compositions by Mendelssohn, although the latter's restrained classicism is reflected in Schumann's later works rather than in those of the 1830s.[36] Early in 1835 he completed two substantial compositions: Carnaval, Op. 9 and the Symphonic Studies, Op.13. These works grew out of his romantic relationship with Ernestine von Fricken, a fellow pupil of Wieck. The musical themes of Carnaval derive from the name of her home town, Asch.[37][n 4] The Symphonic Studies are based on a melody said to be by Ernestine's father, Baron von Fricken, an amateur flautist.[38] Schumann and Ernestine became secretly engaged, but in the view of the musical scholar Joan Chissell, during 1835 Schumann gradually found that Ernestine's personality was not as interesting to him as he first thought, and this, together with his discovery that she was an illegitimate, impecunious, adopted daughter of Fricken, brought the affair to a gradual end.[39] According to the biographer Alan Walker, Ernestine may have been less than frank with Schumann about her background and he was hurt when he learnt the truth.[40]

Schumann felt a growing attraction to Wieck's daughter, the sixteen-year-old Clara. She was her father's star pupil, a piano virtuoso emotionally mature beyond her years, with a developing reputation.[41] According to Chissell, her concerto debut at the Leipzig Gewandhaus on 9 November 1835, with Mendelssohn conducting, "set the seal on all her earlier successes, and there was now no doubting that a great future lay before her as a pianist".[41] Schumann had watched her career approvingly since she was nine, but only now fell in love with her. His feelings were reciprocated: they declared their love to each other in January 1836.[42] Schumann expected that Wieck would welcome the proposed marriage, but he was mistaken: Wieck refused his consent, fearing that Schumann would be unable to provide for his daughter, that she would have to abandon her career, and that she would be legally required to relinquish her inheritance to her husband.[43] It took a series of acrimonious legal actions over the next four years for Schumann to obtain a court ruling that he and Clara were free to marry without her father's consent.[44]

Professionally the later years of the 1830s were marked by an unsuccessful attempt by Schumann to establish himself in Vienna, and a growing friendship with Mendelssohn, who was by then based in Leipzig, conducting the Gewandhaus Orchestra. During this period Schumann wrote many piano works, including Kreisleriana (1837), Davidsbündlertänze (1837), Kinderszenen (Scenes from Childhood, 1838) and Faschingsschwank aus Wien (Carnival Prank from Vienna, 1839).[34] In 1838 Schumann visited Schubert's brother Ferdinand and discovered several manuscripts including that of the Great C major Symphony.[45] Ferdinand allowed him to take a copy away and Schumann arranged for the work's premiere, conducted by Mendelssohn in Leipzig on 21 March 1839.[46] In the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik Schumann wrote enthusiastically about the work and described its "himmlische Länge" – its "heavenly length" – a phrase that has become common currency in later analyses of the symphony.[47][n 5]

1840s

Schumann and Clara finally married on 12 September 1840, the day before her twenty-first birthday.[50] Hall writes that marriage gave Schumann "the emotional and domestic stability on which his subsequent achievements were founded".[34] Clara made some sacrifices in marrying Schumann: as a pianist of international reputation she was the better-known of the two but her career was continually interrupted by motherhood of their seven children. She inspired Schumann in his composing career, encouraging him to extend his range as a composer beyond solo piano works.[34] During 1840 Schumann turned his attention to song, producing more than half his total output of Lieder, including the cycles Myrthen ("Myrtles", a wedding present for Clara), Frauenliebe und Leben ("Woman's Love and Life"), Dichterliebe ("Poet's Love"), and settings of words by Joseph von Eichendorff, Heinrich Heine and others.[34]

In 1841 Schumann focused on orchestral music. On 31 March his First Symphony, The Spring, was premiered by Mendelssohn at a concert in the Gewandhaus at which Clara played Chopin's Second Piano Concerto and some of Schumann's works for solo piano.[51] His next orchestral works were the Overture, Scherzo and Finale, the Phantasie for piano and orchestra (which later became the first movement of the Piano Concerto) and a new symphony (eventually published as the Fourth, in D minor). Clara gave birth to a daughter in September, the first of the Schumanns' seven children to survive.[34]

The following year Schumann turned his attention to chamber music. He studied works by Haydn and Mozart, despite an ambivalent attitude to the former, writing: "Today it is impossible to learn anything new from him. He is like a familiar friend of the house whom all greet with pleasure and with esteem, but who has ceased to arouse any particular interest".[52] He was stronger in his praise of Mozart: "Serenity, repose, grace, the characteristics of the antique works of art, are also those of Mozart's school. The Greeks gave to 'The Thunderer'[n 6] a radiant expression, and radiantly does Mozart launch his lightnings".[54] After his studies Schumann produced three string quartets, a Piano Quintet (premiered in 1843) and a Piano Quartet (premiered in 1844).[34]

In early 1843 there was a setback to Schumann's career: he had a severe and debilitating mental crisis. This was not the first such attack, although it was the worst so far. Hall writes that he had been subject to similar attacks at intervals over a long period, and comments that the condition may have been congenital, affecting August Schumann and Emilie, the composer's sister.[34][n 7] Later in the year, Schumann, having recovered, completed a successful secular oratorio, Das Paradies und die Peri (Paradise and the Peri), based on an oriental poem by Thomas Moore. It was premiered at the Gewandhaus on 4 December and repeat performances followed at Dresden on 23 December, Berlin early the following year, and London in June 1856, when Schumann's friend William Sterndale Bennett conducted a performance given by the Philharmonic Society before Queen Victoria and the Prince Consort.[56] Although neglected after Schumann's death it remained popular throughout his lifetime and brought his name to international attention.[34] During 1843 Mendelssohn invited him to teach piano and composition at the new Leipzig Conservatory,[57] and Wieck approached him with an offer of reconciliation.[31] Schumann gladly accepted both, although the resumed relationship with his father-in-law remained polite rather than close.[31]

In 1844 Clara embarked on a concert tour of Russia; her husband joined her. They met the leading figures of the Russian musical scene, including Mikhail Glinka and Anton Rubinstein and were both immensely impressed by Saint Petersburg and Moscow.[58][59] The tour was an artistic and financial success but it was arduous, and by the end Schumann was in a poor state both physically and mentally.[58] After the couple returned to Leipzig in late May he sold the Neue Zeitschrift, and in December the family moved to Dresden.[58] Schumann had been passed over for the conductorship of the Leipzig Gewandhaus in succession to Mendelssohn, and he thought that Dresden, with a thriving opera house, might be the place where he could, as he now wished, become an operatic composer.[58] His health remained poor. His doctor in Dresden reported complaints "from insomnia, general weakness, auditory disturbances, tremors, and chills in the feet, to a whole range of phobias".[60]

From the beginning of 1845 Schumann's health began to improve; he and Clara studied counterpoint together and both produced contrapuntal works for the piano. He added a slow movement and finale to the 1841 Phantasie for piano and orchestra, to create his Piano Concerto, Op. 54.[61] The following year he worked on what was to be published as his Second Symphony, Op. 61. Progress on the work was slow, interrupted by further bouts of ill health.[62] When the symphony was complete he began work on his opera, Genoveva, which was not completed until August 1848.[63]

Between 24 November 1846 and 4 February 1847 the Schumanns toured to Vienna, Berlin and other cities. The Viennese leg of the tour was not a success. The performance of Schumann's First Symphony and Piano Concerto at the Musikverein on 1 January 1847 attracted a sparse and unenthusiastic audience, but in Berlin the performance of Das Paradies und die Peri was well received, and the tour gave Schumann the chance to see numerous operatic productions. In the words of Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians, "A regular if not always approving member of the audience at performances of works by Donizetti, Rossini, Meyerbeer, Halévy and Flotow, he registered his 'desire to write operas' in his travel diary".[64] The Schumanns suffered several blows during 1847, including the death of their first son, Emil, born the year before, and the deaths of their friends Felix and Fanny Mendelssohn.[45] A second son, Ludwig, and a third, Ferdinand, were born in 1848 and 1849.[45]

1850s

Genoveva, a four-act opera based on the medieval legend of Genevieve of Brabant, was premiered in Leipzig, conducted by the composer, in June 1850. There were two further performances immediately afterwards, but the piece was not the success Schumann had been hoping for. In a 2005 study of the composer, Eric Frederick Jensen attributes this to Schumann's operatic style: "not tuneful and simplistic enough for the majority, not 'progressive' enough for the Wagnerians".[65] Franz Liszt, who was in the first-night audience, revived Genoveva at Weimar in 1855 – the only other production of the opera in Schumann's lifetime.[66] Since then, according to Kobbé's Opera Book, despite occasional revivals Genoveva has remained "far from even the edge of the repertory".[67]

With a large family to support, Schumann sought financial security and with the support of his wife he accepted a post as director of music at Düsseldorf in April 1850. Hall comments that in retrospect it can be seen that Schumann was fundamentally unsuited for the post. In Hall's view, Schumann's diffidence in social situations, allied to mental instability, "ensured that initially warm relations with local musicians gradually deteriorated to the point where his removal became a necessity in 1853".[68] During 1850 Schumann composed two substantial late works – the Third (Rhenish) Symphony and the Cello Concerto.[69] He continued to compose prolifically, and reworked some of his earlier works, including the D minor symphony from 1841, published as his Fourth Symphony (1851), and the 1835 Symphonic Studies (1852).[69]

In 1853 the twenty-year-old Johannes Brahms called on Schumann with a letter of introduction from a mutual friend, the violinist Joseph Joachim. Brahms had recently written the first of his three piano sonatas,[n 8] and played it to Schumann, who rushed excitedly out of the room and came back leading his wife by the hand, saying "Now, my dear Clara, you will hear such music as you never heard before; and you, young man, play the work from the beginning".[71] Schumann was so impressed that he wrote an article – his last – for the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik titled "Neue Bahnen" (New Paths), extolling Brahms as a musician who was destined "to give expression to his times in ideal fashion".[72]

Hall writes that Brahms proved "a personal tower of strength to Clara during the difficult days ahead": in early 1854 Schumann's health deteriorated drastically. On 27 February he attempted suicide by throwing himself into the River Rhine.[68] He was rescued by fishermen, and at his own request he was admitted to a private sanatorium at Endenich, near Bonn, on 4 March. He remained there for more than two years, gradually deteriorating, with intermittent intervals of lucidity during which he wrote and received letters and sometimes essayed some composition.[73] The director of the sanatorium held that direct contact between patients and relatives was likely to distress all concerned and reduce the chances of recovery. Friends, including Brahms and Joachim, were permitted to visit Schumann but Clara did not see her husband until nearly two and a half years into his confinement, and only two days before his death.[73] Schumann died at the sanatorium aged 46 on 29 July 1856, the cause of death being recorded as pneumonia.[74][n 9]

Works

Baker's Biographical Dictionary of Musicians (2001) begins its entry on Schumann: "[G]reat German composer of surpassing imaginative power whose music expressed the deepest spirit of the Romantic era", and concludes: "As both man and musician, Schumann is recognized as the quintessential artist of the Romantic period in German music. He was a master of lyric expression and dramatic power, perhaps best revealed in his outstanding piano music and songs ..."[83][84] Schumann believed the aesthetics of all the arts were identical. In his music he aimed at a conception of art in which the poetic was the main element. According to the musicologist Carl Dahlhaus, for Schumann, "music was supposed to turn into a tone poem, to rise above the realm of the trivial, of tonal mechanics, by means of its spirituality and soulfulness".[85]

In the late nineteenth century and most of the twentieth it was widely held that the music of Schumann's later years was less inspired than his earlier works (up to about the mid-1840s), either because of his declining health,[86] or because his increasingly orthodox approach to composition deprived his music of the Romantic spontaneity of the earlier works.[87][88] The late-nineteenth century composer Felix Draeseke commented "Schumann started as a genius and ended as a talent".[89] In the view of the composer and oboeist Heinz Holliger, "certain works of his early and middle period are praised to the skies, while on the other hand a pious veil of silence obscures the more sober, austere and concentrated works of the late period".[90] More recently the later works have been viewed more favourably; Hall suggests that this is because they are now played more often in concert and in recording studios, and have "the beneficial effects of period performance practice as it has come to be applied to mid-19th-century music".[34]

Solo piano

Schumann's works in some other musical genres – particularly orchestral and operatic works – have had a mixed critical reception, both during his lifetime and since, but there is widespread agreement about the high quality of his solo piano music.[8] In his youth the familiar Austro-German tradition of Bach, Mozart and Beethoven was temporarily eclipsed by a fashion for the flamboyant showpieces of composers such as Moscheles. Schumann's first published work, the Abegg Variations, is in the latter style.[91] But he revered the earlier German masters, and in his three piano sonatas (composed between 1830 and 1836) and the Fantasie in C (1836) he showed his respect for the earlier Austro-German tradition.[92] Absolute music such as those works is in the minority in his piano compositions, of which many are what Hall calls "character pieces with fanciful names".[34]

Schumann's most characteristic form in his piano music is the cycle of short, interrelated pieces, often programmatic, though seldom explicitly so. They include Carnaval, Fantasiestücke, Kreisleriana, Kinderszenen and Waldszenen (Wood Scenes). The critic J. A. Fuller Maitland wrote of the first of these, "Of all the pianoforte works [Carnaval] is perhaps the most popular; its wonderful animation and never-ending variety ensure the production of its full effect, and its great and various difficulties make it the best possible test of a pianist's skill and versatility".[93] Schumann continually inserted into his piano works veiled allusions to himself and others – particularly Clara – in the form of ciphers and musical quotations.[94] His self-references include both the impetuous "Florestan" and the poetic "Eusebius" elements he identified in himself.[95]

Although some of his music is technically challenging for the pianist Schumann also wrote simpler pieces for young players, the best-known of which are his Album für die Jugend (Album for the Young, 1848) and Three Sonatas for Young People (1853).[8] He also wrote some undemanding music with an eye to commercial sales, including the Blumenstück (Flower Piece) and Arabeske (both 1839), which he privately considered "feeble and intended for the ladies".[96]

Songs

The authors of The Record Guide describe Schumann as "one of the four supreme masters of the German Lied", alongside Schubert, Brahms and Hugo Wolf.[97] The pianist Gerald Moore wrote that "after the unparalleled Franz Schubert", Schumann shares the second place in the hierarchy of the Lied with Wolf.[98] Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians classes Schumann as "the true heir of Schubert" in Lieder.[99]

Schumann wrote more than 300 songs for voice and piano.[100] They are known for the quality of the texts he set: Hall comments that the composer's youthful appreciation of literature was constantly renewed in adult life.[101] Although Schumann greatly admired Goethe and Schiller and set a few of their verses, his favoured poets for lyrics were the later Romantics such as Heine, Eichendorff and Mörike.[97]

Among the best-known of the songs are those in four cycles composed in 1840 – a year Schumann called his Liederjahr (year of song).[102] These are Dichterliebe (Poet's Love) comprising sixteen songs with words by Heine; Frauenliebe und Leben (Woman's Love and Life), eight songs setting poems by Adelbert von Chamisso; and two sets simply titled Liederkreis – German for "Song Cycle" – the Op. 24 set, consisting of nine Heine settings and the Op. 39 set of twelve settings of poems by Eichendorff.[103] Also from 1840 is the set Schumann wrote as a wedding present to Clara, Myrthen (Myrtles – traditionally part of a bride's wedding bouquet),[104] which the composer called a song cycle, although comprising twenty-six songs with lyrics from ten different writers this set is a less unified cycle than the others. In a study of Schumann's songs Eric Sams suggests that even here there is a unifying theme, namely the composer himself.[105]

Although during the twentieth century it became common practice to perform these cycles as a whole, in Schumann's time and beyond it was usual to extract individual songs for performance in recitals. The first documented public performance of a complete Schumann song cycle was not until 1861, five years after the composer's death; the baritone Julius Stockhausen sang Dichterliebe with Brahms at the piano.[106] Stockhausen also gave the first complete performances of Frauenliebe und Leben and the Op. 24 Liederkreis.[106]

After his Liederjahr Schumann returned in earnest to writing songs after a break of several years. Hall describes the variety of the songs as immense, and comments that some of the later songs are entirely different in mood from the composer's earlier Romantic settings. Schumann's literary sensibilities led him to create in his songs an equal partnership between words and music unprecedented in the German Lied.[101] His affinity with the piano is heard in his accompaniments to his songs, notably in their preludes and postludes, the latter often summing up what has been heard in the song.[101]

Orchestral

Schumann acknowledged that he found orchestration a difficult art to master, and many analysts have criticised his orchestral writing.[107][n 10] Conductors including Gustav Mahler, Max Reger, Arturo Toscanini, Otto Klemperer and George Szell have made changes to the instrumentation before conducting his orchestral music.[110] The music scholar Julius Harrison considers such alterations fruitless: "the essence of Schumann's warmly vibrant music resides in its forthright romantic appeal with all those personal traits, lovable characteristic and faults" that make up Schumann's artistic character.[111] Hall comments that Schumann's orchestration has subsequently been more highly regarded because of a trend towards playing the orchestral music with smaller forces in historically informed performance.[68]

After the successful premiere in 1841 of the first of his four symphonies the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung described it as "well and fluently written ... also, for the most part, knowledgeably, tastefully, and often quite successfully and effectively orchestrated",[112] although a later critic called it "inflated piano music with mainly routine orchestration".[113] Later in the year a second symphony was premiered and was less enthusiastically received. Schumann revised it ten years later and published it as his Fourth Symphony. Brahms preferred the original, more lightly-scored version,[114] which is occasionally performed and has been recorded, but the revised 1851 score is more usually played.[115] The work now called the Second Symphony (1846) is structurally the most classical of the four and is influenced by Beethoven and Schubert.[116] The Third Symphony (1851), known as the Rhenish, is, unusually for a symphony of its day, in five movements, and is the composer's nearest approach to pictorial symphonic music, with movements depicting a solemn religious ceremony in Cologne Cathedral and outdoor merrymaking of Rhinelanders.[117]

Schumann experimented with unconventional symphonic forms in 1841 in his Overture, Scherzo and Finale, Op. 52, sometimes described as "a symphony without a slow movement".[118] Its unorthodox structure may have made it less appealing and it is not often performed.[119] Schumann composed six overtures, three of them for theatrical performance, preceding Byron's Manfred (1852), Goethe's Faust (1853) and his own Genoveva. The other three were stand-alone concert works inspired by Schiller's The Bride of Messina, Shakespeare's Julius Caesar and Goethe's Hermann and Dorothea.[120]

The Piano Concerto (1845) quickly became and has remained one of the most popular Romantic piano concertos.[121] In the mid-twentieth century, when the symphonies were less well regarded than they later became, the concerto was described in The Record Guide as "the one large-scale work of Schumann's which is by general consent an entire success".[122] The pianist Susan Tomes comments, "In the era of recording it has often been paired with Grieg's Piano Concerto (also in A minor) which clearly shows the influence of Schumann's".[121] The first movement pitches against each other the forthright Florestan and dreamy Eusebius elements in Schumann's artistic nature – the vigorous opening bars succeeded by the wistful A minor theme that enters in the fourth bar.[121] No other concerto or concertante work by Schumann has approached the popularity of the Piano Concerto, but the Concert Piece for Four Horns and Orchestra (1849) and the Cello Concerto (1850) remain in the concert repertoire and are well represented on record.[123] The late Violin Concerto (1853) is less often heard but has received several recordings.[124]

Chamber

Schumann composed a substantial quantity of chamber pieces, of which the best-known and most performed are the Piano Quintet in E♭ major, Op. 44, the Piano Quartet in the same key (both 1842) and three piano trios, the first and second from 1847 and the third from 1851. The Quintet was written for and dedicated to Clara Schumann. It is described by the musicologist Linda Correll Roesner as "a very 'public' and brilliant work that nonetheless manages to incorporate a private message" by quoting a theme composed by Clara.[125] Schumann's writing for piano and string quartet – two violins, one viola and one cello – was in contrast with earlier piano quintets with different combinations of instruments, such as Schubert's Trout Quintet (1819). Schumann's ensemble became the template for later composers including Brahms, Franck, Fauré, Dvořák and Elgar.[126] Roesner describes the Quartet as equally brilliant as the Quintet but also more intimate.[125] Schumann composed a set of three string quartets (Op. 41, 1842). Dahlhaus comments that after this Schumann avoided writing for string quartet, finding Beethoven's achievements in that genre daunting.[127]

Among the later chamber works are the Sonata in A minor for Piano and Violin, Op. 105 – the first of three chamber pieces written in a two-month period of intense creativity in 1851 – followed by the Third Piano Trio and the Sonata in D minor for Violin and Piano, Op. 121.[128]

In addition to his chamber works for what were or were becoming standard combinations of instruments, Schumann wrote for some unusual groupings and was often flexible about which instruments a work called for: in his Adagio and Allegro, Op. 70 the pianist may, according to the composer, be joined by either a horn, a violin or a cello, and in the Fantasiestücke, Op. 73 the pianist may be duetting with a clarinet, violin or cello.[129] His Andante and Variations (1843) for two pianos, two cellos and a horn later became a piece for just the pianos.[129]

Opera and choral

Genoveva was not a great success in Schumann's lifetime and has continued to be a rarity in the opera house. From its premiere onwards the work was criticised on the grounds that it is "an evening of Lieder and nothing much else happens".[130] The conductor Nikolaus Harnoncourt, who championed the work, blamed music critics for the low esteem in which the work is held. He maintained that they all approached the work with a preconceived idea of what an opera must be like, and finding that Genoveva did not match their preconceptions they condemned it out of hand.[131] In Harnoncourt's view it is a mistake to look for a dramatic plot in this opera:

Harnoncourt's view of the lack of drama in the opera contrasts with that of Victoria Bond, who conducted the work's first professional stage production in the US in 1987. She finds the work "full of high drama and supercharged emotion. In my opinion, it's very stageworthy, too. It’s not at all static".[130]

Unlike the opera, Schumann's secular oratorio Das Paradies und die Peri was an enormous success in his lifetime, although it has since been neglected. Tchaikovsky described it as a "divine work" and said he "knew nothing higher in all of music."[133] The conductor Sir Simon Rattle called it "The great masterpiece you've never heard, and there aren't many of those now. ... In Schumann's life it was the most popular piece he ever wrote, it was performed endlessly. Every composer loved it. Wagner wrote how jealous he was that Schumann had done it".[134] Based on an episode from Thomas Moore's epic poem Lalla Rookh it reflects the exotic, colourful tales from Persian mythology popular in the nineteenth century. In a letter to a friend in 1843 Schumann said, "at the moment I'm involved in a large project, the largest I've yet undertaken – it's not an opera – I believe it's well-nigh a new genre for the concert hall".[134]

Szenen aus Goethes Faust (Scenes from Goethe's Faust), composed between 1844 and 1853, is another hybrid work, operatic in manner but written for concert performance and labelled an oratorio by the composer. The work was never given complete in Schumann's lifetime, although the third section was successfully performed in Dresden, Leipzig and Weimar in 1849 to mark the centenary of Goethe's birth. Jensen comments that its good reception is surprising as Schumann made no concessions to popular taste: "The music is not particularly tuneful ... There are no arias for Faust or Gretchen in the grand manner".[135] The complete work was first given in 1862 in Cologne, six years after Schumann's death.[135] Schumann's other works for voice and orchestra include a Requiem Mass, described by the critic Ivan March as "long-neglected and under-prized".[136] Like Mozart before him, Schumann was haunted by the conviction that the Mass was his own requiem.[136]

Recordings

All of Schumann's major works and most of the minor ones have been recorded.[137][138] From the 1920s his music has had a prominent place in the catalogues. In the 1920s Hans Pfitzner recorded the symphonies, and other early recordings were conducted by Georges Enescu and Toscanini.[139] Large-scale performances with modern symphony orchestras have been recorded under conductors including Herbert von Karajan, Wolfgang Sawallisch and Rafael Kubelík,[140] and from the mid-1990s smaller ensembles such as the Orchestre des Champs-Élysées with Philippe Herreweghe and the Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique with John Eliot Gardiner have recorded historically informed readings of Schumann's orchestral music.[140][141]

The songs featured in the recorded repertoire from the early days of the gramophone, with performances by singers such as Elisabeth Schumann (no relation to the composer),[142] Friedrich Schorr, Alexander Kipnis and Richard Tauber, followed in a later generation by Elisabeth Schwarzkopf and Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau.[143] Although in 1955 the authors of The Record Guide expressed regret that so few of Schumann's songs were available on record,[144] by the early twenty-first century every song was on disc. A complete set was published in 2010 with the songs in chronological order of composition; the pianist Graham Johnson partnered a range of singers including Ian Bostridge, Simon Keenlyside, Felicity Lott, Christopher Maltman, Ann Murray and Christine Schäfer.[100] Pianists for other recordings of Schumann Lieder have included Gerald Moore, Dalton Baldwin, Erik Werba, Jörg Demus, Geoffrey Parsons, and more recently Roger Vignoles, Irwin Gage and Ulrich Eisenlohr.[145]

Schumann's solo piano music has remained core repertoire for pianists; there have been numerous recordings of major works played by performers from Sergei Rachmaninoff, Alfred Cortot, Myra Hess and Walter Gieseking to Alfred Brendel, Vladimir Ashkenazy, Martha Argerich, Stephen Hough, Arcadi Volodos and Lang Lang.[146] The chamber works are also well represented in the recording catalogues. In 2023 Gramophone magazine singled out among recent issues recordings of the Piano Quintet by Leif Ove Andsnes and the Artemis Quartet, String Quartets 1 and 3 by the Zehetmair Quartet and the Piano Trios by Andsnes, Christian Tetzlaff and Tanja Tetzlaff.[147]

Schumann's only opera, Genoveva, has been recorded. A 1996 complete set conducted by Harnoncourt with Ruth Ziesak in the title role followed earlier recordings under Gerd Albrecht and Kurt Masur.[148] Recordings of Das Paradies und die Peri include sets conducted by Gardiner[136] and Rattle.[134] Among the recordings of Szenen aus Goethes Faust is one conducted by Benjamin Britten in 1972, with Fischer-Dieskau as Faust and Elizabeth Harwood as Gretchen.[149]

Legacy

Schumann had considerable influence in the nineteenth century and beyond. Those he influenced included French composers such as Fauré and Messager, who made a joint pilgrimage to his tomb at Bonn in 1879,[150] Bizet, Widor, Debussy and Ravel, along with the developers of symbolism.[151] Cortot maintained that Schumann's Kinderscenen inspired Bizet's Jeux d'enfants (Children's Games, 1871), Chabrier's Pièces pittoresques (1881), Debussy's Children's Corner (1908) and Ravel's Ma mère l'Oye (Mother Goose, 1908).[152]

Elsewhere in Europe, Elgar called Schumann "my ideal",[153] and Grieg's Piano Concerto is heavily influenced by Schumann's.[121] Grieg wrote that Schumann's songs deserved to be recognised as "major contributions to world literature",[151] and Schumann was a major influence on the Russian school of composers, including Anton Rubinstein and Tchaikovsky.[154] Tchaikovsky, though critical of Schumann's orchestration, described him as a "composer of genius" and "most striking exponent of the music of our time."[155]

Although Brahms said that all he had learned from Schumann was how to play chess,[156][n 11] his works contain many homages to Schumann. Other composers in German-speaking countries whose music shows Schumann's influence include Mahler, Richard Strauss and Schoenberg.[157] More recently, Schumann has been an important influence on the music of Wolfgang Rihm, who has incorporated elements of Schumann's music into chamber works (Fremde Szenen I–III, (Foreign Scenes, 1982–1984))[158] and his opera Jakob Lenz (1977–1978).[159] Other twentieth and twenty-first century composers drawing on Schumann have included Mauricio Kagel, Wilhelm Killmayer, Henri Pousseur and Robin Holloway.[160]

During the second half of the nineteenth century there developed what became known as the "War of the Romantics". Schumann's successors including Clara and Brahms, together with their supporters such as Joachim and the music critic Eduard Hanslick, were seen as the proponents of music in the classic German tradition of Beethoven, Mendelssohn and Schumann. They were opposed by the adherents of Liszt and Wagner, including Draeseke, Hans von Bülow (for a time) and in his capacity as a music critic Bernard Shaw, who were in favour of more extreme chromatic harmonies and explicit programmatic content.[161] Wagner declared that the symphony was dead.[162] By the turn of the century critics such as Fuller Maitland and Henry Krehbiel were treating the output of both factions with equal regard.[163][164]

In 1991 the first volume of a complete edition of Schumann's works was published. A supposedly complete edition had been published between 1879 and 1887, edited by Clara and Brahms, but it was not complete: apart from inadvertent omissions the two editors deliberately suppressed some of Schumann's later music as they believed it had been affected by his declining mental health.[165] In the 1980s the University of Cologne set up a research department with the aim of locating all the composer's manuscripts. This led to the New Schumann Complete Edition which comprises 49 volumes and was completed in 2023.[165][166]

Schumann's birthplace in Zwickau is preserved as a museum in his honour. It hosts chamber concerts and is the focus of an annual festival commemorating him.[167] The International Robert Schumann Competition for Piano and Voice was launched in Berlin in 1956, and later moved to Zwickau. Among the winners have been the pianists Dezső Ránki, Yves Henry and Éric Le Sage and the singers Siegfried Lorenz, Edith Wiens and Mauro Peter.[168] In 2009 the Royal College of Music in London inaugurated the Joan Chissell Schumann Prize for singers and pianists.[169]

In 2005 the German federal government launched the online Schumann Network in collaboration with cultural institutions in Zwickau, Leipzig, Düsseldorf and Bonn. The site aims to offer the public the most comprehensive coverage of the life and works of Robert and Clara Schumann.[170]

Notes, references and sources

Notes

- ^ a b Many sources from the 19th century onwards state that Schumann had the middle name Alexander,[1] but according to the 2001 edition of Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians and a 2005 biography by Eric Frederick Jensen there is no evidence that he had a middle name and it is possibly a misreading of his teenage pseudonym "Skülander". His birth and death certificates and all other existing official documents give "Robert Schumann" as his only names.[2][3]

- ^ It is not known why Schumann picked those names for his alter egos, although there has been much conjecture over the years.[26] Another of his inventions was "Master Raro", a wise musician of sound judgement, neither so dreamy as Eusebius nor so impetuous as Florestan, sometimes invoked to arbitrate between the two.[27]

- ^ Wieck believed the damage was done by Schumann's use of a chiroplast – a finger-stretching device then favoured by pianists; the biographer Eric Sams has theorised that the affliction was caused by mercury poisoning as a side effect of treatment for syphilis, a hypothesis subsequently discounted by neurologists.[29] Another possible cause may have been dystonia, a condition afflicting several musicians over the years.[30]

- ^ A♭, C, B or in German musical notation "As-C-H"[37]

- ^ The Schubert symphony is not quite as long as Beethoven's Choral Symphony but is much longer than most purely orchestral symphonies to that date, playing for an hour if all the marked repeats are taken. Many performances cut some of the repeats, but, for example, Sir Colin Davis's 1996 complete recording with the Dresden Staatskapelle takes 61 minutes and 50 seconds.[48] None of Schumann's four symphonies play for more than about 35 minutes in typical performances.[49]

- ^ Zeus, Greek god of thunder, known to the Romans as Jupiter, which is the nickname of Mozart's last symphony.[53]

- ^ According to Walker, Emilie's death in 1826 was suicide due to depression and August was unable to recover from the shock of losing his daughter.[55]

- ^ The work was published as Brahms's Second Piano Sonata although it was composed before the other two.[70]

- ^ As with the hand ailment earlier in his life, Schumann's decline and death have been the subject of much conjecture. One theory is that tertiary syphilis, long dormant, was the cause, and the official certification as death from pneumonia was intended to spare Clara's feelings. This view is given varying degrees of credence by Joan Chissell, Alan Walker, John Daverio and Tim Dowley,[75][76][77][78] and is not endorsed by Eric Frederick Jensen, Martin Geck and Ugo Rauchfleisch, who regard the evidence for syphilis as unconvincing.[79][80][81] Another theory is an atrophy of the brain, linked to congenital bipolar disorder: in a 2010 symposium John C. Tibbetts quotes the psychiatrist Peter F. Ostwald: "Did the man have diabetes, did he have liver disease? We don’t know. Did he have an infection? Did he have tuberculosis? We don’t know. These conditions could be remedied today. We could take X-rays of the chest, we could do a test for syphilis, we could treat those conditions with antibiotics. A bipolar affective disorder is eminently treatable today".[82]

- ^ Aspects of Schumann's orchestration for which he has been criticised include (i) string parts that are awkward to play – showing his lack of familiarity with string technique, (ii) a frequent failure to secure a satisfactory balance between melodic and harmonic lines, and, most seriously (iii) his tendency to have string, brass and wind sections playing together most of the time, giving what the composer and musicologist Adam Carse calls a "full-bodied but monotonously rich tint" to the colouring instead of letting the sections of the orchestra be heard on their own at suitable points;[108] the analyst Scott Burnham refers to "an indistinct, muffled quality, in which bass lines can be difficult to discern".[109]

- ^ Dahlhaus regards Brahms's symphonies as in direct descent from Beethoven's, rather than drawing on Schumann.[156]

References

- ^ Liliencron, p. 44; Spitta, p. 384; Slonimsky and Kuhn, p. 3234; and Wolff p. 1702

- ^ a b c Daverio and Sams, p. 760

- ^ Jensen, p. 2

- ^ a b c Perrey, Schumann's lives, p. 6

- ^ Dowley, p. 7

- ^ Chissell, p. 3

- ^ Geck, p. 8

- ^ a b c d e f g h Hall, p. 1125

- ^ Wasielewski, p. 11

- ^ Geck, p. 49

- ^ Chissell, p. 4

- ^ "Schumann around 1826". Schumann Portal. Archived from the original on 5 July 2023. Retrieved 9 June 2024.

- ^ a b Daverio and Sams, p. 761

- ^ Chissell, p. 16

- ^ Jensen, p. 22

- ^ Dowley, p. 27

- ^ Taylor, p. 58

- ^ "Robert Schumann" Archived 13 May 2024 at the Wayback Machine, The Musical Times, Vol. 51, No. 809 (1 July 1910), p. 426

- ^ Jensen, p. 34

- ^ Jensen, p. 37

- ^ Geck, p. 62; and Jensen, p. 97

- ^ Taylor, p. 72

- ^ Jensen, p. 64

- ^ Taylor, p. 74

- ^ Dowley, p. 46

- ^ Sams, Eric. "What's in a Name?" Archived 20 May 2024 at the Wayback Machine, The Musical Times, February 1967, pp. 131–134

- ^ Walker, pp. 55 and 58

- ^ Schumann, p. 15

- ^ a b Ostwald, pp. 23 and 25

- ^ Geck, p. 30; and Hallarman, Lynn. "When I Tried to Play, my Hand Spasmed and Shook" Archived 20 May 2024 at the Wayback Machine, The Guardian, 17 October 2023

- ^ a b c d Slonimsky and Kuhn, pp. 3234–3235

- ^ Daverio and Sams, p. 764

- ^ Daverio and Sams, p. 766

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Hall, p. 1126

- ^ Perrey, Chronology, p. xiv

- ^ Abraham, p. 56

- ^ a b Jones, p. 155

- ^ Davario and Sams, p. 767

- ^ Chissell, p. 36

- ^ Walker, p. 42

- ^ a b Chissell, p. 37

- ^ Chissell, p. 38

- ^ Geck, p. 98

- ^ Daverio and Sams, p. 770

- ^ a b c Perrey, Chronology, p. xv

- ^ Marston, p. 51

- ^ Maintz, p. 100; and Marston, p. 51

- ^ Notes to RCA CD set 09026-62673-2 (1996) OCLC 1378641722

- ^ Notes to: DG CD set 00028948629619 (2022) conducted by Daniel Barenboim OCLC 1370948560; Pye LP set GGCD 302 1–2 (1957) conducted by Sir Adrian Boult OCLC 181675364; EMI CD set 5099909799356 (2011) conducted by Riccardo Muti OCLC 1184268709; and DG CD set 00028947779322 (2009) conducted by Herbert von Karajan OCLC 951273040

- ^ Dowley, p. 66

- ^ Dowley, p. 74

- ^ Schumann, p. 94

- ^ "Jupiter Symphony", The Oxford Companion to Music, Oxford University Press, 2011. Retrieved 20 May 2024 (subscription required) "'Jupiter' Symphony". The Oxford Companion to Music. Oxford University Press. January 2011. ISBN 978-0-19-957903-7. Archived from the original on 20 May 2024. Retrieved 20 May 2024.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Schumann, pp. 94–95

- ^ Walker, p. 21

- ^ Browne Conor. "Robert Schumann's Das Paradies und die Peri and its early performances" Archived 13 May 2024 at the Wayback Machine, Thomas Moore in Europe, Queen's University Belfast, 31 May 2017; and "Philharmonic Concerts", The Times, 24 June 1856, p. 12

- ^ Perrey, Chronology, p. xvi

- ^ a b c d Daverio and Sams, p. 777

- ^ Daverio, p. 286

- ^ Daverio, p. 299

- ^ Daverio, p. 305

- ^ Daverio, p. 298

- ^ Walker, p. 93

- ^ Daverio and Sams, p. 779

- ^ Jensen, p. 235

- ^ Jensen, pp. 316–317

- ^ Harewood, pp. 718–719

- ^ a b c Hall, p. 1127

- ^ a b Perrey, Chronology, p. xvii

- ^ Jensen, p. 271

- ^ Walker, p. 110

- ^ Schumann, pp. 252–254

- ^ a b Daverio and Sams, pp. 788–789

- ^ Daverio, p. 568

- ^ Chissell, p. 77

- ^ Walker, p. 117

- ^ Daverio, p. 484

- ^ Dowley, p. 117

- ^ Jensen, p. 329

- ^ Geck, p. 251

- ^ Rauchfleisch, pp. 164–170

- ^ Tibbetts, pp. 388–389

- ^ Slonimsky and Kuhn, p. 3234

- ^ Slonimsky and Kuhn, p. 3236

- ^ Dahlhaus (1987), p. 214

- ^ Tibbetts, p. 413

- ^ Dahlhaus (1985), pp. 47–48

- ^ Jensen, p. 283

- ^ Batka, p. 77

- ^ Hiekel, p. 261

- ^ Daverio and Sams, p. 762

- ^ Solomon, pp. 41–42

- ^ Fuller Maitland, p. 52

- ^ Daverio and Sams, pp. 755 and 768

- ^ Chissell, p. 88

- ^ Jensen, p. 170

- ^ a b Sackville-West and Shawe-Taylor, p. 686

- ^ Sams, p. vii

- ^ Böker-Heil, Norbert, David Fallows, John H. Baron, James Parsons, Eric Sams, Graham Johnson, and Paul Griffiths. "Lied" Archived 7 October 2022 at the Wayback Machine, Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, 2001 (subscription required)

- ^ a b Johnson, pp. 5–24

- ^ a b c Hall, pp. 1126–1127

- ^ Daverio, p. 191

- ^ Daverio and Sams, pp. 797 and 799

- ^ Finson (2007), p. 21

- ^ Sams, p. 50

- ^ a b Reich p. 222

- ^ Daverio and Sams, pp. 789 and 792; and Burnham, pp. 152–153

- ^ Carse, p. 264

- ^ Burnham, p. 152

- ^ Frank, p. 200; Heyworth, p. 36; Kapp, p. 239; and "Schumann Symphonies; Manfred – Overture", Gramophone, February 1997 (registration required) Archived 16 May 2024 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Harrison, p. 249

- ^ Finson (1989), p. 1

- ^ Abraham, Gerald, quoted in Burnham, p. 152

- ^ Harrison, p. 247

- ^ March, et al, pp. 1139–1140

- ^ Harrison, pp. 252–253

- ^ Harrison, p. 255

- ^ Burnham, p. 157; and Abraham, p. 53

- ^ Burnham, p. 158

- ^ Burnham, pp. 163–164

- ^ a b c d Tomes, p. 126

- ^ Sackville-West and Shawe-Taylor, p. 678

- ^ March et al, pp. 1134, 1138 and 1140

- ^ March et al, p. 1137

- ^ a b Roesner, p. 133

- ^ "List of Compositions for Piano Quintet" Archived 9 January 2024 at the Wayback Machine, International Music Score Library Project. Retrieved 17 May 2024

- ^ Dahlhaus (1989), p. 78

- ^ Roesner, p. 123

- ^ a b Daverio and Sams, p. 794

- ^ a b Tibbetts, p. 308

- ^ Cowan, Rob. "Schumann Genoveva" Archived 17 May 2024 at the Wayback Machine, Gramophone, January 1998 (registration required)

- ^ "Schumann: Genoveva" Archived 18 May 2024 at the Wayback Machine, Nikolaus Harnoncourt. Retrieved 18 May 2024

- ^ Жизнь Петра Ильича Чайковского, том 1 (1997), p. 229–230.

- ^ a b c "Schumann: Das Paradies und die Peri" Archived 18 March 2024 at the Wayback Machine, London Symphony Orchestra. Retrieved 18 May 2024

- ^ a b Jensen, p. 233

- ^ a b c March et al, p. 1150

- ^ March et al, pp. 1133–1150

- ^ Kapp, pp. 242 and 247

- ^ "Robert Schumann", Naxos Music Library. Retrieved 17 May 2024 (subscription required) Archived 20 May 2024 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b March et al, pp. 1138–1139

- ^ "Robert Schumann: Complete Symphonies", Harmonia Mundi, 2007 OCLC 1005955733

- ^ Gammond, p. 191

- ^ Sackville-West and Shawe-Taylor, pp. 688–689; and March et al, p. 1148

- ^ Sackville-West and Shawe-Taylor, p. 687

- ^ March et al, pp. 1147–1149; and "Robert Schumann", Naxos Music Library. Retrieved 17 May 2024 (subscription required) Archived 20 May 2024 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ March et al, pp. 1144–1147; and "Robert Schumann", Naxos Music Library. Retrieved 17 May 2024 (subscription required) Archived 20 May 2024 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Robert Schumann: 12 Gramophone Award-winning Recordings", Gramophone, 15 May 2023 (registration required) Archived 17 May 2024 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Schumann Genoveva", Gramophone, January 1998 (registration required) Archived 17 May 2024 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Stuart, Philip. Decca Classical, 1929–2009 Archived 4 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine, AHRC Research Centre for the History and Analysis of Recorded Music. Retrieved 30 May 2024

- ^ Nectoux, p. 277

- ^ a b Daverio and Sams, p. 792

- ^ Brody, p. 206

- ^ Moore, p. 97

- ^ Kapp, p. 237

- ^ The second concert of the Russian Musical Society. mr Slavyansky’s Russian concert. The Second Concert of the Russian Musical Society. Mr Slavyansky’s Russian Concert - Tchaikovsky Research. (n.d.). https://en.tchaikovsky-research.net/pages/The_Second_Concert_of_the_Russian_Musical_Society._Mr_Slavyansky%27s_Russian_Concert

- ^ a b Dahlhaus (1989), p. 153

- ^ Kapp, p. 245

- ^ Williams, p. 379

- ^ Williams, p. 380

- ^ Williams, pp. 384–385

- ^ Anderson, Robert. "Shaw, (George) Bernard", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, 2001 (subscription required) "Shaw, (George) Bernard". Archived from the original on 20 May 2024. Retrieved 20 May 2024.; and Larkin, pp. 85–86, 88 and 91

- ^ Dahlhaus (1989), p. 265

- ^ Obituary, J. A. Fuller Maitland, The Times 31 March 1936, p. 11

- ^ Krehbiel, p. 226

- ^ a b Tibbetts, pp. 413–414

- ^ "Robert Schumann: New Edition of Complete Works" Archived 20 May 2024 at the Wayback Machine, Schott Music Group. Retrieved 20 May 2024

- ^ Robert Schumann House Archived 12 August 2021 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 16 May 2024

- ^ "Internationaler Robert-Schumann-Wettbewerb" Archived 3 February 2022 at the Wayback Machine, Robert Schumann Haus, Zwickau (in German). Retrieved 21 May 2024

- ^ Warrack, John. "Chissell, Joan Olive (1919–2007), Music Critic", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2011 (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- ^ "Welcome to the Schumann Network!" Archived 28 September 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Schumann Netzwerk. Retrieved 20 May 2024; and "Clara und Robert Schumann" Archived 28 May 2024 at the Wayback Machine, City of Bonn (in German). Retrieved 28 May 2024

Sources

- Abraham, Gerald (1974). A Hundred Years of Music. London: Duckworth. OCLC 3074351.

- Batka, Richard (1891). Schumann (in German). Leipzig: Reclam. OCLC 929462354.

- Brody, Elaine (Summer 1974). "Schumann's Legacy in France". Studies in Romanticism. 13 (3): 189–212. doi:10.2307/25599933. JSTOR 25599933.(subscription required)

- Burnham, Scott (2007). "Novel Symphonies and Dramatic Overtures". In Beate Perrey (ed.). Cambridge Companion to Schumann. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-00154-0.

- Carse, Adam (1964). The History of Orchestration. New York: Dover. ISBN 978-0-48-621258-6.

- Chissell, Joan (1989). Schumann (Fifth ed.). London: Dent. ISBN 978-0-46-012588-8.

- Dahlhaus, Carl (1985). Realism in Nineteenth-Century Music. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52-126115-9.

- Dahlhaus, Carl (1987). Schoenberg and the New Music: Essays. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52-133251-4.

- Dahlhaus, Carl (1989). Nineteenth-Century Music. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-07644-0.

- Daverio, John (1997). Robert Schumann: Herald of a "New Poetic Age". New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-509180-9.

- Daverio, John; Eric Sams (2000). "Schumann, Robert". In Stanley Sadie (ed.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Vol. 22. London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-56159-239-5. OCLC 905948998.

- Dowley, Tim (1982). Schumann: His Life and Times. Neptune City: Paganiniana. ISBN 978-0-87-666634-0.

- Finson, Jon W. (1989). Robert Schumann and the Study of Orchestral Composition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-313213-9.

- Finson, Jon W. (2007). Robert Schumann. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-67-402629-2.

- Frank, Mortimer H. (2002). Arturo Toscanini: The NBC Years. Portland: Amadeus Press. ISBN 978-1-57-467069-1.

- Fuller Maitland, J. A. (1884). Schumann. London: S. Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington. OCLC 9892895.

- Gammond, Peter (1995). The Harmony Illustrated Encyclopedia of Classical Music. London: Salamander. ISBN 978-0-86-101400-2.

- Geck, Martin (2013) [2010]. Robert Schumann: The Life and Work of a Romantic Composer. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-22-628469-9.

- Hall, George (2002). "Robert Schumann". In Alison Latham (ed.). Oxford Companion to Music. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-866212-9.

- Harrison, Julius (1967). "Robert Schumann". In Robert Simpson (ed.). The Symphony: Haydn to Dvořák. Harmondsworth: Pelican Books. OCLC 221594461.

- Harewood, Earl of (2000). "Robert Schumann". In Earl of Harewood; Antony Peattie (eds.). The New Kobbé's Opera Book (eleventh ed.). London: Ebury Press. ISBN 978-0-09-181410-6.

- Heyworth, Peter (1985) [1973]. Conversations with Klemperer (second ed.). London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-57113-561-5.

- Hiekel, Jörn Peter (2007). "The Compositional Reception of Schumann's Music Since 1950". In Beate Perrey (ed.). Cambridge Companion to Schumann. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-00154-0.

- Jensen, Eric Frederick (2005). Schumann. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-983068-8.

- Johnson, Graham (2010). Schumann: The Complete Songs. London: Hyperion. OCLC 680498810.

- Jones, J. Barrie (1998). "Piano Music for Concert Hall and Salon c. 1830–1900". In David Rowland (ed.). Cambridge Companion to the Piano. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-00208-0.

- Kapp, Reinhard (2007). "Schumann in His Time and Since". In Beate Perrey (ed.). Cambridge Companion to Schumann. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-00154-0.

- Krehbiel, Henry (1911). The Pianoforte and its Music. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. OCLC 1264303.

- Larkin, David (2021). "The 'War' of the Romantics". In Joanne Cormac (ed.). Liszt in Context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-10-842184-3.

- Liliencron, Rochus von (1875). Allgemeine deutsche Biographie (in German). Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot. OCLC 311366924.

- Maintz, Marie Luise (1995). Franz Schubert in der Rezeption Robert Schumanns: Studien zur Ästhetik und Instrumentalmusik (in German). Kassel and New York: Bärenreiter. ISBN 978-3-76-181244-0.

- March, Ivan; Edward Greenfield; Robert Layton; Paul Czajkowski (2008). The Penguin Guide to Recorded Classical Music 2009. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-141-03335-8.

- Marston, Philip (2007). "Schumann's Heroes". In Beate Perrey (ed.). Cambridge Companion to Schumann. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-00154-0.

- Moore, Jerrold Northrop (1984). Edward Elgar: a Creative Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-315447-6.

- Nectoux, Jean-Michel (1991). Gabriel Fauré: A Musical Life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52-123524-2.

- Ostwald, Peter (Summer 1980). "Florestan, Eusebius, Clara, and Schumann's Right Hand". 19th-Century Music. 4 (1): 17–31. doi:10.2307/3519811. JSTOR 3519811. Archived from the original on 12 May 2024. Retrieved 17 May 2024.(subscription required)

- Perrey, Beate (2007). "Chronology". In Beate Perrey (ed.). Cambridge Companion to Schumann. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-00154-0.

- Perrey, Beate (2007). "Schumann's lives, and afterlives". In Beate Perrey (ed.). Cambridge Companion to Schumann. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-00154-0.

- Rauchfleisch, Udo (1990). Robert Schumann: Werk und Leben (in German). Stuttgart: Kohlhammer. ISBN 978-3-17-010945-2.

- Reich, Nancy B. (1988). Clara Schumann: The Artist and the Woman. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-80-149388-1.

- Roesner, Linda Correll (2007). "The Chamber Works". In Beate Perrey (ed.). Cambridge Companion to Schumann. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-00154-0.

- Sackville-West, Edward; Desmond Shawe-Taylor (1955). The Record Guide. London: Collins. OCLC 500373060.

- Sams, Eric (1969). The Songs of Robert Schumann. London: Methuen. ISBN 978-0-41-610390-8.

- Schumann, Robert (1946). Konrad Wolff (ed.). On Music and Musicians. New York: Norton. OCLC 583002.

- Slonimsky, Nicolas; Laura Kuhn, eds. (2001). Baker's Biographical Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Vol. 5. New York: Schirmer. ISBN 978-0-02-865530-7.

- Solomon, Yonty (1972). "Solo Piano Music (I): The Sonatas and Fantasie". In Alan Walker (ed.). Robert Schumann: The Man and His Music. New York: Barnes & Noble. ISBN 978-0-06-497367-0. OCLC 1330614595.

- Spitta, Philipp (1879). "Schumann, Robert". In George Grove (ed.). A Dictionary of Music and Musicians. London and New York: Macmillan. OCLC 1043255406.

- Taylor, Ronald (1985) [1982]. Robert Schumann: His Life and Work. London: Panther. ISBN 978-0-58-605883-1.

- Tibbetts, John C. (2010). Schumann: A Chorus of Voices. New York: Amadeus Press. ISBN 978-1-57467-185-8.

- Tomes, Susan (2021). The Piano: A History in 100 Pieces. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-30-026286-5.

- Walker, Alan (1976). Schumann. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-57-110269-3.

- Wasielewski, Wilhelm Joseph von (1869). Robert Schumann: Eine Biographie (in German). Dresden: Kuntze. OCLC 492828443. Archived from the original on 20 May 2024. Retrieved 17 May 2024.

- Williams, Alastair (August 2006). "Swaying with Schumann: Subjectivity and Tradition in Wolfgang Rihm's "Fremde Szenen" I-III and Related Scores". Music and Letters. 87 (3): 379–397. doi:10.1093/ml/gci234. JSTOR 3876905.(subscription required)

- Wolff, Anita, ed. (2006). Britannica Concise Encyclopedia. Chicago: Britannica. ISBN 978-1-59339-492-9.

External links

- The Schumann Network – German government-sponsored site

- "Discovering Schumann". BBC Radio 3.

- The city of Robert Schumann

- Works by or about Robert Schumann at the Internet Archive (texts)

- Free scores by Robert Schumann at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Works by or about Robert Schumann at the Internet Archive (audio and video)

- Works by Robert Schumann at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)