Bourbon Restoration in France

Kingdom of France Royaume de France (French) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1815–1830 | |||||||||

| Motto: Montjoie Saint Denis! | |||||||||

| Anthem: Le Retour des Princes français à Paris "The Return of the French Princes to Paris" | |||||||||

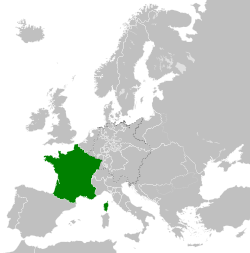

The Kingdom of France in 1818 | |||||||||

| Capital | Paris | ||||||||

| Common languages | French | ||||||||

| Religion | |||||||||

| Demonym(s) | French | ||||||||

| Government | Unitary parliamentary semi-constitutional monarchy | ||||||||

| King | |||||||||

• 1815–1824 | Louis XVIII | ||||||||

• 1824–1830 | Charles X | ||||||||

| President of the Council of Ministers | |||||||||

• 1815 | Charles de Talleyrand-Périgord | ||||||||

• 1829–1830 | Jules de Polignac | ||||||||

| Legislature | Parliament | ||||||||

| Chamber of Peers | |||||||||

| Chamber of Deputies | |||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Restoration | 1815 | ||||||||

• Charter of 1815 adopted | 1815 | ||||||||

| 6 April 1823 | |||||||||

| 26 July 1830 | |||||||||

| Currency | French franc | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| History of France |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

| Topics |

|

|

| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in France |

|---|

|

The Second Bourbon Restoration was the period of French history during which the House of Bourbon returned to power after the fall of Napoleon in 1815. The Second Bourbon Restoration lasted until the July Revolution of 26 July 1830. Louis XVIII and Charles X, brothers of the executed King Louis XVI, successively mounted the throne and instituted a conservative government intended to restore the proprieties, if not all the institutions, of the Ancien régime. Exiled supporters of the monarchy returned to France but were unable to reverse most of the changes made by the French Revolution. Exhausted by the Napoleonic Wars, the nation experienced a period of internal and external peace, stable economic prosperity and the preliminaries of industrialization.[3]

Background

Following the French Revolution (1789–1799), Napoleon Bonaparte became ruler of France. After years of expansion of his French Empire by successive military victories, a coalition of European powers defeated him in the War of the Sixth Coalition, ended the First Empire in 1814, and restored the monarchy to the brothers of Louis XVI. The First Bourbon Restoration lasted from about 6 April 1814. In July 1815 the First French Empire was succeeded by the Kingdom of France. This Kingdom existed until the popular uprisings of the July Revolution of 1830.[citation needed]

At the peace Congress of Vienna, the Bourbons were treated politely by the victorious monarchies, but had to give up nearly all the territorial gains made by revolutionary and Napoleonic France since 1789.[citation needed]

Constitutional monarchy

Unlike the absolutist Ancien Régime, the Restoration Bourbon regime was a constitutional monarchy, with some limits on its power. The new king, Louis XVIII, accepted the vast majority of reforms instituted from 1792 to 1814. Continuity was his basic policy. He did not try to recover land and property taken from the royalist exiles. He continued in peaceful fashion the main objectives of Napoleon's foreign policy, such as the limitation of Austrian influence. He reversed Napoleon regarding Spain and the Ottoman Empire, restoring the friendships that had prevailed until 1792.[4]

Politically, the period was characterized by a sharp conservative reaction, and consequent minor but persistent civil unrest and disturbances.[5] Otherwise, the political establishment was relatively stable until the subsequent reign of Charles X.[3] It also saw the reestablishment of the Catholic Church as a major power in French politics.[6] Throughout the Bourbon Restoration, France experienced a period of stable economic prosperity and the preliminaries of industrialisation.[3]

Permanent changes in French society

The eras of the French Revolution and Napoleon brought a series of major changes to France which the Bourbon Restoration did not reverse.[7][8][9]

Administration: First, France was now highly centralised, with all important decisions made in Paris. The political geography was completely reorganised and made uniform, dividing the nation into more than 80 départements which have endured into the 21st century. Each department had an identical administrative structure, and was tightly controlled by a prefect appointed by Paris. The thicket of overlapping legal jurisdictions of the old regime had all been abolished, and there was now one standardised legal code, administered by judges appointed by Paris, and supported by police under national control.[citation needed]

The church: The Revolutionary governments had confiscated all the lands and buildings of the Catholic Church, selling them to innumerable middle-class buyers, and it was politically impossible to restore them. The bishop still ruled his diocese (which was aligned with the new department boundaries) and communicated with the pope through the government in Paris. Bishops, priests, nuns and other religious were paid state salaries.[citation needed]

All the old religious rites and ceremonies were retained, and the government maintained the religious buildings. The Church was allowed to operate its own seminaries and to some extent local schools as well, although this became a central political issue into the 20th century. Bishops were much less powerful than before, and had no political voice. However, the Catholic Church reinvented itself with a new emphasis on personal piety that gave it a hold on the psychology of the faithful.[10]

Education: Public education was centralised, with the Grand Master of the University of France controlling every element of the national educational system from Paris. New technical universities were opened in Paris which to this day have a critical role in training the elite.[11]

The aristocracy: Conservatism was bitterly split into the returning old aristocracy and the new elites arising under Napoleon after 1796. The old aristocracy was eager to regain its land, but felt no loyalty to the new regime. The newer elite, the "noblesse d'empire", ridiculed the older group as an outdated remnant of a discredited regime that had led the nation to disaster. Both groups shared a fear of social disorder, but the level of distrust as well as the cultural differences were too great, and the monarchy too inconsistent in its policies, for political cooperation to be possible.[12]

The returning old aristocracy recovered much of the land they had owned directly. However, they lost all their old seigneurial rights to the rest of the farmland, and the peasants were no longer under their control. The pre-Revolutionary aristocracy had dallied with the ideas of the Enlightenment and rationalism. Now the aristocracy was much more conservative and supportive of the Catholic Church. For the best jobs, meritocracy was the new policy, and aristocrats had to compete directly with the growing business and professional class.[citation needed]

Citizens' rights: Public anti-clerical sentiment became stronger than ever before, but was now based in certain elements of the middle class and even the peasantry. The great masses of French people were peasants in the countryside or impoverished workers in the cities. They gained new rights and a new sense of possibilities. Although relieved of many of the old burdens, controls, and taxes, the peasantry was still highly traditional in its social and economic behaviour. Many eagerly took on mortgages to buy as much land as possible for their children, so debt was an important factor in their calculations. The working class in the cities was a small element, and had been freed of many restrictions imposed by medieval guilds. However, France was very slow to industrialise, and much of the work remained drudgery without machinery or technology to help. France was still split into localities, especially in terms of language, but now there was an emerging French nationalism that focused national pride in the Army and foreign affairs.[13]

Political overview

In April 1814, the Armies of the Sixth Coalition restored Louis XVIII of France to the throne, the brother and heir of the executed Louis XVI. A constitution was drafted: the Charter of 1814. It presented all Frenchmen as equal before the law,[14] but retained substantial prerogatives for the king and nobility and limited voting to those paying at least 300 Francs a year in direct taxes.

The king was the supreme head of the state. He commanded the land and sea forces, declared war, made treaties of peace, alliance and commerce, appointed all public officials, and made the necessary regulations and ordinances for the execution of the laws and the security of the state.[15] Louis was relatively liberal, choosing many centrist cabinets.[16]

Louis XVIII died in September 1824 and was succeeded by his brother, who reigned as Charles X. The new king pursued a more conservative form of governance than Louis. His more reactionary laws included the Anti-Sacrilege Act (1825–1830). Exasperated by public resistance and disrespect, the king and his ministers attempted to manipulate the general election of 1830 through their July Ordinances. This sparked a revolution in the streets of Paris, Charles abdicated, and on 9 August 1830 the Chamber of Deputies affirmed Louis Phillipe d'Orleans as King of the French, ushering in the July Monarchy.

Louis XVIII, 1814–1824

First Restoration (1814)

Louis XVIII's restoration to the throne in 1814 was effected largely through the support of Napoleon's former foreign minister, Talleyrand, who convinced the victorious Allied Powers of the desirability of a Bourbon Restoration.[17] The Allies had initially split on the best candidate for the throne: Britain favoured the Bourbons, the Austrians considered a regency for Napoleon's son, the King of Rome, and the Russians were open to either the duc d'Orléans, Louis Philippe, or Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte, Napoleon's former Marshal, who was heir-presumptive to the Swedish throne. Napoleon was offered to keep the throne in February 1814, on the condition that France return to its 1792 frontiers, but he refused.[17] The feasibility of the Restoration was in doubt, but the allure of peace to a war-weary French public, and demonstrations of support for the Bourbons in Paris, Bordeaux, Marseille, and Lyon, helped reassure the Allies.[18]

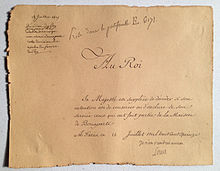

Louis, in accordance with the Declaration of Saint-Ouen,[19] granted a written constitution, the Charter of 1814, which guaranteed a bicameral legislature with a hereditary/appointive Chamber of Peers and an elected Chamber of Deputies – their role was consultative (except on taxation), as only the King had the power to propose or sanction laws, and appoint or recall ministers.[20] The franchise was limited to men with considerable property holdings, and just 1% of people could vote.[20] Many of the legal, administrative, and economic reforms of the revolutionary period were left intact; the Napoleonic Code,[20] which guaranteed legal equality and civil liberties, the peasants' biens nationaux, and the new system of dividing the country into départments were not undone by the new king. Relations between church and state remained regulated by the Concordat of 1801. However, in spite of the fact that the Charter was a condition of the Restoration, the preamble declared it to be a "concession and grant", given "by the free exercise of our royal authority".[21]

After a first sentimental flush of popularity, Louis' gestures towards reversing the results of the French Revolution quickly lost him support among the disenfranchised majority. Symbolic acts such as the replacement of the tricolore flag with the white flag, the titling of Louis as the "XVIII" (as successor to Louis XVII, who never ruled) and as "King of France" rather than "King of the French", and the monarchy's recognition of the anniversaries of the deaths of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette were significant. A more tangible source of antagonism was the pressure applied to possessors of biens nationaux (the lands confiscated by the revolution) by the Catholic Church and the returning émigrés' attempts to repossess their former lands.[22] Other groups bearing ill-feeling towards Louis included the army, non-Catholics, and workers hit by a post-war slump and British imports.[1]

The Hundred Days

Napoleon's emissaries informed him of this brewing discontent,[1] and, on 20 March 1815, he returned to Paris from Elba. On his Route Napoléon, most troops sent to stop his march, including some that were nominally royalist, felt more inclined to join the former Emperor than to stop him.[23] Louis fled from Paris to Ghent on 19 March.[24][25]

After Napoleon was defeated in the Battle of Waterloo and sent again into exile, Louis returned. During his absence a small revolt in the traditionally pro-royalist Vendée was put down but there were otherwise few subversive acts favouring the Restoration, even though Napoleon's popularity began to flag.[26]

Second Restoration (1815)

Talleyrand was again influential in seeing that the Bourbons were restored to power, as was Joseph Fouché,[27][28] Napoleon's minister of police during the Hundred Days. This Second Restoration saw the beginning of the Second White Terror, largely in the south, when unofficial groups supporting the monarchy sought revenge against those who had aided Napoleon's return: about 200–300 were killed, while thousands fled. About 70,000 government officials were dismissed. The pro-Bourbon perpetrators were often known as the Verdets because of their green cockets, which was the colour of the comte d'Artois – this being the title of Charles X at the time, who was associated with the hardline ultra-royalists, or Ultras. After a period in which local authorities looked on helplessly at the violence, the King and his ministers sent out officials to restore order.[29]

A new Treaty of Paris was signed on 20 November 1815, which had more punitive terms than the 1814 treaty. France was ordered to pay 700 million francs in indemnities, and the country's borders were reduced to their 1790 status, rather than 1792 as in the previous treaty. Until 1818, France was occupied by 1.2 million foreign soldiers, including around 200,000 under the command of the Duke of Wellington, and France was made to pay the costs of their accommodation and rations, on top of the reparations.[30][31] The promise of tax cuts, prominent in 1814, was impracticable because of these payments. The legacy of this, and the White Terror, left Louis with a formidable opposition.[30]

Louis's chief ministers were at first moderate,[32] including Talleyrand, the Duc de Richelieu, and Élie, duc Decazes; Louis himself followed a cautious policy.[33] The chambre introuvable, elected in 1815, given the nickname "unobtainable" by Louis, was dominated by an overwhelming ultra-royalist majority which quickly acquired the reputation of being "more royalist than the king". The legislature threw out the Talleyrand-Fouché government and sought to legitimize the White Terror, passing judgement against enemies of the state, sacking 50,000–80,000 civil servants, and dismissing 15,000 army officers.[30] Richelieu, an émigré who had left in October 1789, who " had nothing at all to do with the new France",[33] was appointed Prime Minister. The chambre introuvable, meanwhile, continued to aggressively uphold the place of the monarchy and the church, and called for more commemorations for historical royal figures.[b] Over the course of the parliamentary term, the ultra-royalists increasingly began to fuse their brand of politics with state ceremony, much to Louis' chagrin.[35] Decazes, perhaps the most moderate minister, moved to stop the politicisation of the National Guard (many Verdets had been drafted in) by banning political demonstrations by the militia in July 1816.[36]

Owing to tension between the King's government and the ultra-royalist Chamber of Deputies, the latter began to assert their rights. After they attempted to obstruct the 1816 budget, the government conceded that the chamber had the right to approve state expenditure. However, they were unable to gain a guarantee from the King that his cabinets would represent the majority in parliament.[37]

In September 1816, the chamber was dissolved by Louis for its reactionary measures, and electoral manipulation[citation needed] resulted in a more liberal chamber in 1816. Richelieu served until 29 December 1818, followed by Jean-Joseph, Marquis Dessolles until 19 November 1819, and then Decazes (in reality the dominant minister from 1818 to 1820)[38][39] until 20 February 1820. This was the era in which the Doctrinaires dominated policy, hoping to reconcile the monarchy with the French Revolution and power with liberty. The following year, the government changed the electoral laws, resorting to gerrymandering, and altering the franchise to allow some rich men of trade and industry to vote,[40] in an attempt to prevent the ultras from winning a majority in future elections. Press censorship was clarified and relaxed, some positions in the military hierarchy were made open to competition, and mutual schools were set up that encroached on the Catholic monopoly of public primary education.[41][42] Decazes purged a number of ultra-royalist prefects and sub-prefects, and in by-elections, an unusually high proportion of Bonapartists and republicans were elected, some of whom were backed by ultras resorting to tactical voting.[38] The ultras were strongly critical of the practice of giving civil service employment or promotions to deputies, as the government continued to consolidate its position.[43]

By 1820, the opposition liberals—who, with the ultras, made up half the chamber—proved unmanageable, and Decazes and the king were looking for ways to revise the electoral laws again, to ensure a more tractable conservative majority. In February 1820, the assassination by a Bonapartist of the Duc de Berry, the ultrareactionary son of Louis' ultrareactionary brother and heir-presumptive, the future Charles X, triggered Decazes' fall from power and the triumph of the Ultras.[44]

Richelieu returned to power for a short interval, from 1820 to 1821. The press was more strongly censored, detention without trial was reintroduced, and Doctrinaire leaders, such as François Guizot, were banned from teaching at the École Normale Supérieure.[44][45] Under Richelieu, the franchise was changed to give the wealthiest electors a double vote, in time for the November 1820 election. After a resounding victory, a new Ultra ministry was formed, headed by Jean-Baptiste de Villèle, a leading Ultra who served for six years. The ultras found themselves back in power in favourable circumstances: Berry's wife, the duchesse de Berry, gave birth to a "miracle child", Henri, seven months after the duc's death; Napoleon died on Saint Helena in 1821, and his son, the duc de Reichstadt, remained interned in Austrian hands. Literary figures, most notably Chateaubriand, but also Hugo, Lamartine, Vigny, and Nodier, rallied to the ultras' cause. Both Hugo and Lamartine later became republicans, whilst Nodier was formerly.[46][47] Soon, however, Villèle proved himself to be nearly as cautious as his master, and, so long as Louis lived, overtly reactionary policies were kept to a minimum.[citation needed]

The ultras broadened their support, and put a stop to growing military dissent in 1823, when intervention in Spain, in favour of Spanish Bourbon King Ferdinand VII, and against the Liberal Spanish Government, fomented popular patriotic fervour. Despite British backing for the military action, the intervention was widely seen as an attempt to win back influence in Spain, which had been lost to the British under Napoleon. The French expeditionary army, called the Hundred Thousand Sons of Saint Louis, was led by the duc d'Angoulême, the comte d'Artois's son. The French troops marched to Madrid and then to Cádiz, ousting the Liberals with little fighting (April to September 1823), and would remain in Spain for five years. Support for the ultras amongst the voting rich was further strengthened by doling out favours in a similar fashion to the 1816 chamber, and fears over the charbonnerie, the French equivalent of the carbonari. In the 1824 election, another large majority was secured.[48]

Louis XVIII died on 16 September 1824 and was succeeded by his brother, the Comte d'Artois, who took the title of Charles X.[citation needed]

Charles X

1824–1830: Conservative turn

The accession to the throne of Charles X, the leader of the ultra-royalist faction, coincided with the ultras' control of power in the Chamber of Deputies; thus, the ministry of the comte de Villèle was able to continue. The restraint Louis had exercised on the ultra-royalists was removed.[citation needed]

As the country underwent a Christian revival in the post-revolutionary years, the ultras worked to raise the status of the Roman Catholic Church once more. The Church and State Concordat of 11 June 1817 was set to replace the Concordat of 1801, but, despite being signed, it was never validated. The Villèle government, under pressure from the Chevaliers de la Foi including many deputies, voted in the Anti-Sacrilege Act in January 1825, which punished by death the theft of consecrated hosts. The law was unenforceable and only enacted for symbolic purposes, though the act's passing caused a considerable uproar, particularly among the Doctrinaires.[49] Much more controversial was the introduction of the Jesuits, who set up a network of colleges for elite youth outside the official university system. The Jesuits were noted for their loyalty to the Pope and gave much less support to Gallican traditions. Inside and outside the Church they had enemies, and the king ended their institutional role in 1828.[50]

New legislation paid an indemnity to royalists whose lands had been confiscated during the Revolution. Although this law had been engineered by Louis, Charles was influential in seeing that it was passed. A bill to finance this compensation, by converting government debt (the rente) from 5% to 3% bonds, which would save the state 30 million francs a year in interest payments, was also put before the chambers. Villèle's government argued that rentiers had seen their returns grow disproportionately to their original investment, and that the redistribution was just. The final law allocated state funds of 988 million francs for compensation (le milliard des émigrés), financed by government bonds at a value of 600 million francs at 3% interest. Around 18 million francs were paid per year.[51] Unexpected beneficiaries of the law were some one million owners of biens nationaux, the old confiscated lands, whose property rights were now confirmed by the new law, leading to a sharp rise in its value.[52]

On 29 May 1825 the Coronation of Charles X took place at Reims Cathedral, the traditional site of French coronations. In 1826, Villèle introduced a bill reestablishing the law of primogeniture, at least for owners of large estates, unless they chose otherwise. The liberals and the press rebelled, as did some dissident ultras, such as Chateaubriand. Their vociferous criticism prompted the government to introduce a bill to restrict the press in December, having largely withdrawn censorship in 1824. This only inflamed the opposition even more, and the bill was withdrawn.[53]

The Villèle cabinet faced increasing pressure in 1827 from the liberal press, including the Journal des débats, which sponsored Chateaubriand's articles. Chateaubriand, the most prominent of the anti-Villèle ultras, had combined with other opponents of press censorship (a new law had reimposed it on 24 July 1827) to form the Société des amis de la liberté de la presse; Choiseul-Stainville, Salvandy and Villemain were among the contributors.[54] Another influential society was the Société Aide-toi, le ciel t'aidera, which worked within the confines of legislation banning the unauthorized meetings of more than 20 members. The group, emboldened by the rising tide of opposition, was of a more liberal composition (associated with Le Globe) and included members such as Guizot, Rémusat, and Barrot.[55] Pamphlets were sent out which evaded the censorship laws, and the group provided organizational assistance to liberal candidates against pro-government state officials in the November 1827 election.[56]

In April 1827, the King and Villèle were confronted by an unruly National Guard. The garrison which Charles reviewed, under orders to express deference to the king but disapproval of his government, instead shouted derogatory anti-Jesuit remarks at his devoutly Catholic niece and daughter in law, Marie Thérèse, Madame la Dauphine. Villèle suffered worse treatment, as liberal officers led troops to protest at his office. In response, the Guard was disbanded.[56] Pamphlets continued to proliferate, which included accusations in September that Charles, on a trip to Saint-Omer, was colluding with the Pope and planned to reinstate the tithe, and had suspended the Charter under the protection of a loyal garrison army.[57]

By the time of the election, the moderate royalists (constitutionalists) were also beginning to turn against Charles, as was the business community, in part due to a financial crisis in 1825, which they blamed on the government's law of indemnification.[58][59] Hugo and a number of other writers, dissatisfied with the reality of life under Charles X, also began to criticize the regime.[60] In preparation for the 30 September registration cut-off for the election, opposition committees worked furiously to get as many voters as possible signed up, countering the actions of préfects, who began removing certain voters who had failed to provide up-to-date documents since the 1824 election. 18,000 voters were added to the 60,000 on the first list; despite préfect attempts to register those who met the franchise and were supporters of the government, this can mainly be attributed to opposition activity.[61] Organization was mainly divided behind Chateaubriand's Friends and the Aide-toi, which backed liberals, constitutionnels, and the contre-opposition (constitutional monarchists).[62]

The new chamber did not result in a clear majority for any side. Villèle's successor, the vicomte de Martignac, who began his term in January 1828, tried to steer a middle course, appeasing liberals by loosening press controls, expelling Jesuits, modifying electoral registration, and restricting the formation of Catholic schools.[63] Charles, unhappy with the new government, surrounded himself with men from the Chevaliers de la Foi and other ultras, such as the Prince de Polignac and La Bourdonnaye. Martignac was deposed when his government lost a bill on local government. Charles and his advisers believed a new government could be formed with the support of the Villèle, Chateaubriand, and Decazes monarchist factions, but chose a chief minister, Polignac, in November 1829 who was repellent to the liberals and, worse, Chateaubriand. Though Charles remained nonchalant, the deadlock led some royalists to call for a coup, and prominent liberals for a tax strike.[64]

At the opening of the session in March 1830, the King delivered a speech that contained veiled threats to the opposition; in response, 221 deputies (an absolute majority) condemned the government, and Charles subsequently prorogued and then dissolved parliament. Charles retained a belief that he was popular amongst the unenfranchised mass of the people, and he and Polignac chose to pursue an ambitious foreign policy of colonialism and expansionism, with the assistance of Russia. France had intervened in the Mediterranean a number of times after Villèle's resignation, and expeditions were now sent to Greece and Madagascar. Polignac also initiated the French conquest of Algeria; victory was announced over the Dey of Algiers in early July. Plans were drawn up to invade Belgium, which was shortly to undergo its own revolution. However, foreign policy did not prove sufficient to divert attention from domestic problems.[65][66]

Charles's dissolution of the Chamber of Deputies, his July Ordinances which set up rigid control of the press, and his restriction of suffrage resulted in the July Revolution of 1830. The major cause of the regime's downfall, however, was that, while it managed to keep the support of the aristocracy, the Catholic Church and even much of the peasantry, the ultras' cause was deeply unpopular outside of parliament and with those who did not hold the franchise,[67] especially the industrial workers and the bourgeoisie.[68] A major reason was a sharp rise in food prices, caused by a series of bad harvests 1827–1830. Workers living on the margin were very hard-pressed, and angry that the government paid little attention to their urgent needs.[69]

Charles abdicated in favor of his grandson, the Comte de Chambord, and left for England. However, the liberal, bourgeois-controlled Chamber of Deputies refused to confirm the Comte de Chambord as Henry V. In a vote largely boycotted by conservative deputies, the body declared the French throne vacant, and elevated Louis-Philippe, Duke of Orléans, to power.[citation needed]

1827–1830: Tensions

There is still considerable debate among historians as to the actual cause of the downfall of Charles X. What is generally conceded, though, is that between 1820 and 1830, a series of economic downturns combined with the rise of a liberal opposition within the Chamber of Deputies, ultimately felled the conservative Bourbons.[70]

Between 1827 and 1830, France faced an economic downturn, industrial and agricultural, that was possibly worse than the one that sparked the revolution. A series of progressively worsening grain harvests in the late 1820s pushed up the prices on various staple foods and cash crops.[71] In response, the rural peasantry throughout France lobbied for the relaxation of protective tariffs on grain to lower prices and ease their economic situation. However, Charles X, bowing to pressure from wealthier landowners, kept the tariffs in place. He did so based upon the Bourbon response to the "Year Without a Summer" in 1816, during which Louis XVIII relaxed tariffs during a series of famines, caused a downturn in prices, and incurred the ire of wealthy landowners, who were the traditional source of Bourbon legitimacy. Thus, between 1827 and 1830, peasants throughout France faced a period of relative economic hardship and rising prices.

At the same time, international pressures, combined with weakened purchasing power from the provinces, led to decreased economic activity in urban centers. This industrial downturn contributed to the rising poverty levels among Parisian artisans. Thus, by 1830, multiple demographics had suffered from the economic policies of Charles X.[citation needed]

While the French economy faltered, a series of elections brought a relatively powerful liberal bloc into the Chamber of Deputies. The 17-strong liberal bloc of 1824 grew to 180 in 1827, and 274 in 1830. This liberal majority grew increasingly dissatisfied with the policies of the centrist Martignac and the ultra-royalist Polignac, seeking to protect the limited protections of the Charter of 1814. They sought both the expansion of the franchise, and more liberal economic policies. They also demanded the right, as the majority bloc, to appoint the Prime Minister and the Cabinet.[citation needed]

Also, the growth of the liberal bloc within the Chamber of Deputies corresponded roughly with the rise of a liberal press within France. Generally centered around Paris, this press provided a counterpoint to the government's journalistic services, and to the newspapers of the right. It grew increasingly important in conveying political opinions and the political situation to the Parisian public, and can thus be seen as a crucial link between the rise of the liberals and the increasingly agitated and economically suffering French masses.[citation needed]

By 1830, the Restoration government of Charles X faced difficulties on all sides. The new liberal majority clearly had no intention of budging in the face of Polignac's aggressive policies. The rise of a liberal press within Paris which outsold the official government newspaper indicated a general shift in Parisian politics towards the left. And yet, Charles' base of power was certainly toward the right of the political spectrum, as were his own views. He simply could not yield to the growing demands from within the Chamber of Deputies. The situation would soon come to a head.[citation needed]

1830: The July Revolution

The Charter of 1814 had made France a constitutional monarchy. While the king retained extensive power over policy-making, as well as the sole power of the Executive, he was, nonetheless, reliant upon the Parliament to accept and pass his legal decrees.[72] The Charter also fixed the method of election of the Deputies, their rights within the Chamber of Deputies, and the rights of the majority bloc. Thus, in 1830, Charles X faced a significant problem. He could not overstep his constitutional bounds, and yet, he could not pursue his policies with a liberal majority within the Chamber of Deputies. He was ready for stark action and made his move after a final no-confidence vote by the liberal house majority, in March 1830. He set about to alter the Charter of 1814 by decree. These decrees, known as the "Four Ordinances", dissolved the Chamber of Deputies, suspended the liberty of the press, excluded the more liberal commercial middle-class from future elections, and called for new elections.[73]

Opinion was outraged. On 10 July 1830, before the king had even made his declarations, a group of wealthy, liberal journalists and newspaper proprietors, led by Adolphe Thiers, met in Paris to decide upon a strategy to counter Charles X. It was decided then, nearly three weeks before the Revolution, that in the event of Charles' expected proclamations, the journalistic establishment of Paris would publish vitriolic criticisms of the king's policies in an attempt to mobilise the masses. Thus, when Charles X made his declarations on 25 July 1830, the liberal journalism machine mobilised, publishing articles and complaints decrying the despotism of the king's actions.[74]

The urban mobs of Paris also mobilised, driven by patriotic fervour and economic hardship, assembling barricades and attacking the infrastructure of Charles X. Within days, the situation escalated beyond the ability of the monarchy to control it. As the Crown moved to shut down liberal periodicals, the radical Parisian masses defended those publications. They also launched attacks against pro-Bourbon presses, and paralysed the coercive apparatus of the monarchy. Seizing the opportunity, the liberals in Parliament began drafting resolutions, complaints, and censures against the king. The king finally abdicated on 30 July 1830. Twenty minutes later, his son, Louis Antoine, Duke of Angoulême, who had nominally succeeded as Louis XIX, also abdicated. The Crown nominally then fell upon the son of Louis Antoine's younger brother, Charles X's grandson, who was in line to become Henry V. However, the newly empowered Chamber of Deputies declared the throne vacant, and on 9 August, elevated Louis-Philippe, to the throne. Thus, the July Monarchy began.[75]

Louis-Philippe and the House of Orléans

Louis-Philippe ascended the throne on the strength of the July Revolution of 1830, and ruled, not as "King of France" but as "King of the French", marking the shift to national sovereignty. The Orléanists remained in power until 1848. Following the ousting of the last king to rule France during the February 1848 Revolution, the French Second Republic was formed with the election of Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte as President (1848–1852). In the French coup of 1851, Napoleon declared himself Emperor Napoleon III of the Second Empire, which lasted from 1852 to 1870.[citation needed]

Political parties under Restoration

Political parties saw substantial changes of alignment and membership under the Restoration. The Chamber of Deputies oscillated between repressive ultra-royalist phases and progressive liberal phases. The repression of the White Terror excluded opponents of the monarchy from the political scene, but individuals of influence who had different visions of the French constitutional monarchy still clashed.[76][77]

All parties remained fearful of the common people, who had no voting rights and whom Adolphe Thiers later referred to by the term "cheap multitude". Their political sights were set on a class favoritism. Political changes in the Chamber were due to abuse by the majority tendency, involving a dissolution and then an inversion of the majority, or critical events; for example, the assassination of the Duc de Berry in 1820.[citation needed]

Disputes were a power struggle between the powerful (royalty against deputies) rather than a fight between royalty and populism. Although the deputies claimed to defend the interests of the people, most had an important fear of common people, of innovations, of socialism and even of simple measures, such as the extension of voting rights.[citation needed]

The principal political parties during the Restoration are described below.

Ultra-royalists

The Ultra-royalists wished for a return to the Ancien Régime which prevailed before 1789: absolute monarchy, domination by the nobility, and the monopoly of politics by "devoted Christians". They were anti-Republican, anti-democratic, and preached Government on High. Although they tolerated vote censitaire, a form of democracy limited to those paying taxes above a high threshold, they found the Charter of 1814 to be too revolutionary. They wanted a re-establishment of privileges, a major political role for the Catholic Church, and a politically active, rather than ceremonial, king: Charles X.[78]

Prominent ultra-royalist theorists were Louis de Bonald and Joseph de Maistre. Their parliamentary leaders were François Régis de La Bourdonnaye, comte de La Bretèche and, in 1829, Jules de Polignac. The main royalist newspapers were La Quotidienne and La Gazette, supplemented by the Drapeau Blanc, named after the Bourbon white flag, and the Oriflamme, named after the battle standard of France.[citation needed]

Doctrinaires

The Doctrinaires were mostly rich and educated middle-class men: lawyers, senior officials of the Empire, and academics. They feared the triumph of the aristocracy, as much as that of the democrats. They accepted the Royal Charter as a guarantee of freedom and civil equality which nevertheless reined in the ignorant and excitable masses. Ideologically they were classical liberals who formed the centre-right of the Restoration's political spectrum: they upheld both capitalism and Catholicism, and attempted to reconcile parliamentarism (in an elite, wealth-based form) and monarchism (in a constitutional, ceremonial form), while rejecting both the absolutism and clericalism of the Ultra-Royalists, and the universal suffrage of the liberal left and republicans. Important personalities were Pierre Paul Royer-Collard, François Guizot, and the count of Serre. Their newspapers were Le Courrier français and Le Censeur.[79]

Liberal Left

The Liberals were mostly petite-bourgeoisie: doctors and lawyers, men of law, and, in rural constituencies, merchants and traders of national goods. Electorally they benefitted from the slow emergence of a new middle-class elite, due to the start of the Industrial Revolution.[citation needed]

Some of them accepted the principle of monarchy, in a strictly ceremonial and parliamentary form, while others were moderate republicans. Constitutional issues aside, they agreed on seeking to restore the democratic principles of the French Revolution, such as the weakening of clerical and aristocratic power, and therefore thought the constitutional Charter was not sufficiently democratic, and disliked the peace treaties of 1815, the White Terror and the return to pre-eminence of clergy and of nobility. They wished to lower the taxable quota to support the middle-class as a whole, to the detriment of the aristocracy, and thus they supported universal suffrage or at least a wide opening-up of the electoral system to the modest middle-classes such as farmers and craftsmen. Important personalities were parliamentary monarchist Benjamin Constant, officer of the Empire Maximilien Sebastien Foy, republican lawyer Jacques-Antoine Manuel, and the Marquis de Lafayette. Their newspapers were La Minerve, Le Constitutionnel, and Le Globe.[80]

Republicans and Socialists

The only active Republicans were on the left to far-left, based among the workers. Workers had no vote and were not listened to. Their demonstrations were repressed or diverted, causing, at most, a reinforcement of parliamentarism, which did not mean democratic evolution, only wider taxation. For some, such as Blanqui, revolution seemed the only solution. Garnier-Pagès, and Louis-Eugène and Éléonore-Louis Godefroi Cavaignac considered themselves to be Republicans, while Cabet and Raspail were active as socialists. Saint-Simon was also active during this period, and made direct appeals to Louis XVIII before his death in 1824.[81]

Religion

By 1800 the Catholic Church was poor, dilapidated and disorganised, with a depleted and aging clergy. The younger generation had received little religious instruction, and was unfamiliar with traditional worship.[82] However, in response to the external pressures of foreign wars, religious fervour was strong, especially among women.[83] Napoleon's Concordat of 1801 provided stability and ended attacks on the Church.

With the Restoration, the Catholic Church again became the state religion, supported financially and politically by the government. Its lands and financial endowments were not returned, but the government paid salaries and maintenance costs for normal church activities. The bishops regained control of Catholic affairs. The aristocracy before the Revolution was lukewarm to religious doctrine and practice, but the decades of exile created an alliance of throne and altar. The royalists who returned were much more devout, and much more aware of their need for a close alliance with the Church. They had discarded fashionable skepticism and now promoted the wave of Catholic religiosity that was sweeping Europe, with a new reverence for the Virgin Mary, the saints, and popular religious rituals such as praying the rosary. Devotion was far stronger and more visible in rural areas than in Paris and other cities. The population of 32 million included about 680,000 Protestants and 60,000 Jews, who were extended toleration. The anti-clericalism of Voltaire and the Enlightenment had not disappeared, but it was in abeyance.[84]

At the elite level, there was a dramatic change in intellectual climate from intellectual classicism to passionate romanticism. An 1802 book by François-René de Chateaubriand entitled Génie du christianisme ("The Genius of Christianity") had an enormous influence in reshaping French literature and intellectual life, emphasising the centrality of religion in creating European high culture. Chateaubriand's book "did more than any other single work to restore the credibility and prestige of Christianity in intellectual circles and launched a fashionable rediscovery of the Middle Ages and their Christian civilisation. The revival was by no means confined to an intellectual elite, however, but was evident in the real, if uneven, rechristianisation of the French countryside."[85]

Economy

With the restoration of the Bourbons in 1814, the reactionary aristocracy with its disdain for entrepreneurship returned to power. British goods flooded the market, and France responded with high tariffs and protectionism to protect its established businesses, especially handcrafts and small-scale manufacturing such as textiles. The tariff on iron goods reached 120%.[86] Agriculture had never needed protection, but now demanded it due to the lower prices of imported foodstuffs, such as Russian grain. French winegrowers strongly supported the tariff – their wines did not need it, but they insisted on a high tariff on the import of tea. One agrarian deputy explained: "Tea breaks down our national character by converting those who use it often into cold and stuffy Nordic types, while wine arouses in the soul that gentle gaiety that gives Frenchmen their amiable and witty national character."[87] The French government falsified official statistics to claim that exports and imports were growing – actually there was stagnation, and the economic crisis of 1826–29 disillusioned the business community and readied them to support the revolution in 1830.[88]

Art and literature

Romanticism reshaped art and literature.[89] It stimulated the emergence of a wide new middle class audience.[90] Among the most popular works were:

- Les Misérables, Victor Hugo's novel which is set in the 20 years after Napoleon's Hundred Days

- The Red and the Black, Stendhal's novel set in the final years of the regime

- La Comédie humaine, a sequence of almost 100 novels and plays by Honoré de Balzac, set during the Restoration and the July Monarchy

Paris

The city grew slowly in population from 714,000 in 1817 to 786,000 in 1831. During the period Parisians saw the first public transport system, the first gas street lights, and the first uniformed Paris policemen. In July 1830, a popular uprising in the streets of Paris brought down the Bourbon monarchy.[91]

Memory and historical evaluation

After two decades of war and revolution, the restoration brought peace and quiet, and general prosperity. Gordon Wright says, "Frenchmen were, on the whole, well governed, prosperous, contented during the 15-year period; one historian even describes the restoration era as 'one of the happiest periods in [France's] history.[92]

France had recovered from the strain and disorganization, the wars, the killings, the horrors, of two decades of disruption. It was at peace throughout the period. It paid a large war indemnity to the winners, but managed to finance that without distress; the occupation soldiers left peacefully. France's population increased by three million, and prosperity was strong from 1815 to 1825, with the depression of 1825 caused by bad harvests. The national credit was strong, there was significant increase in public wealth, and the national budget showed a surplus every year. In the private sector, banking grew dramatically, making Paris a world center for finance, along with London. The Rothschild family was world-famous, with the French branch led by James Mayer de Rothschild (1792–1868). The communication system was improved, as roads were upgraded, canals were lengthened, and steamboat traffic became common. Industrialization was delayed in comparison to Britain and Belgium. The railway system had yet to make an appearance. Industry was heavily protected with tariffs, so there was little demand for entrepreneurship or innovation.[93][94]

Culture flourished with the new romantic impulses. Oratory was highly regarded, and sophisticated debate flourished. Châteaubriand and Madame de Stael (1766–1817) enjoyed Europe-wide reputations for their innovations in romantic literature. She made important contributions to political sociology, and the sociology of literature.[95] History flourished; François Guizot, Benjamin Constant and Madame de Staël drew lessons from the past to guide the future.[96] The paintings of Eugène Delacroix set the standards for romantic art. Music, theater, science, and philosophy all flourished.[97] Higher learning flourished at the Sorbonne. Major new institutions gave France world leadership in numerous advanced fields, as typified by the École Nationale des Chartes (1821) for historiography, the École Centrale des Arts et Manufactures in 1829 for innovative engineering; and the École des Beaux-Arts for the fine arts, reestablished in 1830.[98]

Charles X repeatedly exacerbated internal tensions, and tried to neutralize his enemies with repressive measures. They totally failed and forced him into exile for the third time. However the government's handling of foreign affairs was a success. France kept a low profile, and Europe forgot its animosities. Louis and Charles had little interest in foreign affairs, so France played only minor roles. For example, it helped the other powers deal with Greece and Turkey. Charles X mistakenly thought that foreign glory would cover domestic frustration, so he made an all-out effort to conquer Algiers in 1830. He sent a massive force of 38,000 soldiers and 4,500 horses carried by 103 warships and 469 merchant ships. The expedition was a dramatic military success.[99] It even paid for itself with captured treasures. The episode launched the second French colonial empire, but it did not provide desperately needed political support for the King at home.[100]

Restoration in recent popular culture

The 2007 French historical film Jacquou le Croquant, directed by Laurent Boutonnat and starring Gaspard Ulliel and Marie-Josée Croze, is based on the Bourbon Restoration.

See also

- French Restoration style

- Pierre Louis Jean Casimir de Blacas

- Mathieu de Montmorency

- French Empire mantel clock

- French monarchs family tree

- France in the long nineteenth century

- French Republicans under the Restoration

Notes

- ^ The flag can be seen on top of government buildings in the following illustrations:

- Retour du Roi le 8 juillet 1815. parismuseescollections.paris.fr. 1815. Retrieved 12 December 2021.

- Attaque Des Tuileries (le 29 Juillet 1830). gallica.bnf.fr. 1830. Retrieved 25 November 2023.

- ^ Furet 1995, p. 282 This included blocking the budget over plans to guarantee bonds on the sale of 400,000 hectares of forest previously owned by the church, reintroducing prohibition of divorce, demanding the death penalty for individuals found with the tricolore, and attempting to hand civil registers back to the church.[34]

References

- ^ a b c Tombs 1996, p. 333.

- ^ Pinoteau, Hervé (1998). Le chaos français et ses signes: étude sur la symbolique de l'Etat français depuis la Révolution de 1789 (in French). Presses Sainte-Radegonde. p. 217. ISBN 978-2-9085-7117-2. OL 456931M.

- ^ a b c Sauvigny 1966.

- ^ Rooney, John W. Jr.; Reinerman, Alan J. (1986). "Continuity: French Foreign Policy Of The First Restoration". Consortium on Revolutionary Europe 1750–1850: Proceedings. 16: 275–288.

- ^ Davies 2002, pp. 47–54.

- ^ Furet 1995, p. 296.

- ^ Wolf 1962, pp. 4–27.

- ^ McPhee, Peter (1992). A Social History of France 1780–1880. Routledge. pp. 93–173. ISBN 0-4150-1616-9. OL 15032217M.

- ^ Charle, Christophe (1994). A Social History of France in the 19th Century. Berg Publishers. pp. 7–27. ISBN 978-0-8549-6913-5. OL 1107847M.

- ^ McMillan, James F. (2014). "Catholic Christianity in France from the Restoration to the separation of church and state, 1815–1905". In Gilley, Sheridan; Stanley, Brian (eds.). The Cambridge History of Christianity. Vol. 8. pp. 217–232.

- ^ Barnard, H.C. (1969). Education and French Revolution. Cambridge University press. p. 223. ISBN 0-5210-7256-5. OL 21492257M.

- ^ Anderson, Gordon K. (1994). "Old Nobles and Noblesse d'Empire, 1814–1830: In Search of a Conservative Interest in Post-Revolutionary France". French History. 8 (2): 149–166. doi:10.1093/fh/8.2.149.

- ^ Wolf 1962, pp. 9, 19–21.

- ^ The Charter of 1814, Public Law of the French: Article 1

- ^ The Charter of 1814, Form of the Government of the King: Article 14

- ^ Price 2008, p. 93.

- ^ a b Tombs 1996, p. 329.

- ^ Tombs 1996, pp. 330–331.

- ^ Furet 1995, p. 271.

- ^ a b c Furet 1995, p. 272.

- ^ Tombs 1996, p. 332.

- ^ Tombs 1996, pp. 332–333.

- ^ Ingram 1998, p. 43

- ^ Tombs 1996, p. 334.

- ^ Furet 1995, p. 278.

- ^ Alexander 2003, pp. 32, 33.

- ^ Tombs 1996, p. 335.

- ^ Furet 1995, p. 279.

- ^ Tombs 1996, p. 336.

- ^ a b c Tombs 1996, p. 337.

- ^ EM staff 1918, p. 161.

- ^ Bury 2003, p. 19.

- ^ a b Furet 1995, p. 281.

- ^ Alexander 2003, pp. 37, 38.

- ^ Alexander 2003, p. 39.

- ^ Alexander 2003, pp. 54, 58.

- ^ Alexander 2003, p. 36.

- ^ a b Tombs 1996, p. 338.

- ^ Furet 1995, p. 289.

- ^ Furet 1995, pp. 289, 290.

- ^ Furet 1995, p. 290.

- ^ Alexander 2003, p. 99.

- ^ Alexander 2003, p. 81.

- ^ a b Tombs 1996, p. 339.

- ^ Furet 1995, p. 291.

- ^ Tombs 1996, p. 340.

- ^ Furet 1995, p. 295.

- ^ Tombs 1996, pp. 340–341; Crawley 1969, p. 681

- ^ Tombs 1996, pp. 341–342.

- ^ BN (Barbara Neave, comtesse de Courson) (1879). The Jesuits: their foundation and history. New York: Benziger Brothers. p. 305.

- ^ Price 2008, pp. 116–117.

- ^ Tombs 1996, pp. 342–343.

- ^ Tombs 1996, pp. 344–345.

- ^ Kent 1975, pp. 81–83.

- ^ Kent 1975, pp. 84–89.

- ^ a b Tombs 1996, p. 345.

- ^ Kent 1975, p. 111.

- ^ Tombs 1996, p. 344.

- ^ Kent 1975, pp. 107–110.

- ^ Tombs 1996, pp. 346–347.

- ^ Kent 1975, p. 116.

- ^ Kent 1975, p. 121.

- ^ Tombs 1996, p. 348.

- ^ Tombs 1996, pp. 348–349.

- ^ Tombs 1996, pp. 349–350.

- ^ Bury 2003, pp. 39, 42.

- ^ Bury 2003, p. 34.

- ^ Hudson 1973, pp. 182, 183

- ^ Pinkney, David H. (1961). "A new look at the French revolution of 1830". Review of Politics. 23 (4): 490–506. doi:10.1017/S003467050002307X.

- ^ Pilbeam 1999, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Bury 2003, p. 38.

- ^ Bury 2003, pp. 33–44.

- ^ Leepson, Marc (2011). Lafayette: Lessons in Leadership from the Idealist General. St. Martin's Press. p. 167. ISBN 978-0-2301-0504-1. OCLC 651011968. OL 26007181M.

- ^ Schroeder, Paul W. (1996). The Transformation of European Politics, 1763–1848. Clarendon Press. pp. 666–670. ISBN 978-0-1982-0654-5. OL 28536287M.

- ^ Waller, Sally (2002). France in Revolution, 1776–1830. Heinemann Advanced History. Heinemann Educational Publishers. pp. 134–135. ISBN 978-0-4353-2732-3. OL 7508502M.

- ^ Artz 1931, pp. 9–99.

- ^ Bury 2003, pp. 18–44.

- ^ Hudson 1973.

- ^ Johnson, Douglas (1963). Guizot: Aspects of French History, 1787–1874. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8371-8566-8. OCLC 233745. OL 5875905M.

- ^ Dennis Wood, Benjamin Constant: A Biography (1993).

- ^ Kirkup 1892, p. 21.

- ^ History Review 68 (2010): 16–21.

- ^ Tombs 1996, p. 241.

- ^ Artz 1931, pp. 99–171.

- ^ McMillan 2014, pp. 217–232.

- ^ Caron, François (1979). An economic history of modern France. pp. 95–96.

- ^ Wright, Gordon (1995). France in Modern Times: From the Enlightenment to the Present. W. W. Norton. p. 147. ISBN 978-0-3939-6705-0. OL 1099419M.

- ^ Milward, Alan S.; Saul, S. Berrick (1973). Economic Development of Continental Europe, 1780–1870. Allen & Unwin. pp. 307–364. OL 5476145M.

- ^ Stewart, Restoration Era (1968), pp. 83–87.

- ^ James Smith Allen, Popular French Romanticism: Authors, Readers, and Books in the 19th Century (1981)

- ^ Colin Jones, Paris: The Biography of a City (2006) pp 263–299.

- ^ Wright 1995, p. 105, quoting Sauvigny 1966

- ^ Bury 2003, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Clapham, John H. (1936). The Economic Development of France and Germany 1815–1914. pp. 53–81, 104–107, 121–127.

- ^ Germaine de Stael and Monroe Berger, Politics, Literature, and National Character (2000)

- ^ Lucian Robinson, "Accounts of early Christian history in the thought of François Guizot, Benjamin Constant and Madame de Staël 1800–c. 1833." History of European Ideas 43#6 (2017): 628–648.

- ^ Michael Marrinan, Romantic Paris: histories of a cultural landscape, 1800–1850 (2009).

- ^ Pierre Bourdieu (1998). The State Nobility: Elite Schools in the Field of Power. Stanford UP. pp. 133–135. ISBN 9780804733465. Archived from the original on 2023-09-28. Retrieved 2018-07-02.

- ^ Nigel Falls, "The Conquest of Algiers," History Today (2005) 55#10 pp 44–51.

- ^ Bury 2003, pp. 43–44.

Works cited

- Alexander, Robert (2003). Re-Writing the French Revolutionary Tradition: Liberal Opposition and the Fall of the Bourbon Monarchy. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-5218-0122-2.

- Artz, Frederick Binkerd (1931). France Under the Bourbon Restoration, 1814-1830. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-8462-0380-3. OL 26840286M.

- Bury, J.P.T. (2003) [1949]. France, 1814–1940. Routledge. ISBN 0-4153-1600-6.

- Crawley, C. W. (1969). The New Cambridge Modern History. Volume IX: War and Peace in an Age of Upheaval, 1793–1830. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-5210-4547-6.

- Davies, Peter (2002). The Extreme Right in France, 1789 to the Present: From De Maistre to Le Pen. Routledge. ISBN 0-4152-3982-6.

- EM staff (January 1918). "State Papers". The European Magazine, and London Review. Philological Society (Great Britain): 161.

- Furet, François (1995). Revolutionary France 1770-1880. pp. 269–325. survey of political history by leading scholar

- Hudson, Nora Eileen (1973). Ultra-Royalism and the French Restoration. Octagon Press. ISBN 0-3749-4027-4.

- Ingram, Philip (1998). Napoleon and Europe. Nelson Thornes. ISBN 0-7487-3954-8.

- Kent, Sherman (1975). The Election of 1827 in France. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-6742-4321-8. OL 5185010M.

- Kirkup, T. (1892). A History of Socialism. London: Adam and Charles Black.

- Pilbeam, Pamela (1999). Alexander, Martin S. (ed.). French History Since Napoleon. Arnold. ISBN 0-3406-7731-7.

- Price, Munro. (2008). The Perilous Crown: France between Revolutions. Pan. ISBN 978-0-3304-2638-1.

- Sauvigny, Guillaume de Bertier de (1966). The Bourbon Restoration.

- Tombs, Robert (1996). France 1814–1914. London: Longman. ISBN 0-5824-9314-5.

- Wolf, John B. (1962). France: 1814–1919: The Rise of a liberal-Democratic Society (France, 1815 to the present) (2nd ed.). pp. 4–27.

Further reading

- Artz, Frederick B. (1929). "The Electoral System in France during the Bourbon Restoration, 1815–30". Journal of Modern History. 1 (2): 205–218. doi:10.1086/235451. JSTOR 1872004.

- —— (1934). Reaction and Revolution, 1814–1832.

- Beach, Vincent W. (1971) Charles X of France: His Life and Times (Boulder: Pruett, 1971) 488 pp

- Brogan, D. W. (January 1956). "The French Restoration: 1814–1830 (Part 1)". History Today. 6 (1): 28–36.

- —— (February 1956). "The French Restoration: 1814–1830 (Part 2)". History Today. 6 (2): 104–109.

- Charle, Christophe. (1994) A Social History of France in the 19th Century (1994) pp 1–52

- Collingham, Hugh A. C. (1988). The July Monarchy: A Political History of France, 1830–1848. London: Longman. ISBN 0-5820-2186-3.

- Counter, Andrew J. "A Nation of Foreigners: Chateaubriand and Repatriation." Nineteenth-Century French Studies 46.3 (2018): 285–306. online Archived 2018-07-01 at the Wayback Machine

- Fenby, Jonathan (October 2015). "Return of the King". History Today. 65 (10): 49–54.

- Fortescue, William. (1988) Revolution and Counter-revolution in France, 1815–1852 (Blackwell, 1988).

- Fozzard, Irene (1951). "The Government and the Press in France, 1822 to 1827". English Historical Review. 66 (258): 51–66. doi:10.1093/ehr/LXVI.CCLVIII.51. JSTOR 556487.

- Hall, John R. The Bourbon Restoration (1909) online free

- Haynes, Christine. Our Friends the Enemies. The Occupation of France after Napoleon (Harvard University Press, 2018) online reviews Archived 2020-02-25 at the Wayback Machine

- Jardin, Andre; Tudesq, Andre-Jean (1988). Restoration and Reaction 1815–1848.

- Kelly, George A. "Liberalism and aristocracy in the French Restoration." Journal of the History of Ideas 26.4 (1965): 509–530. Online Archived 30 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- Kieswetter, James K. "The Imperial Restoration: Continuity in Personnel and Policy under Napoleon I and Louis XVIII." Historian 45.1 (1982): 31–46. online

- Knapton, Ernest John. (1934) "Some Aspects of the Bourbon Restoration of 1814." Journal of Modern History (1934) 6#4 pp: 405–424. in JSTOR Archived 2016-03-12 at the Wayback Machine

- Kroen, Sheryl T. (Winter 1998). "Revolutionizing Religious Politics during the Restoration". French Historical Studies. 21 (1): 27–53. doi:10.2307/286925. JSTOR 286925.

- Lucas-Dubreton, Jean (1929). The Restoration and the July Monarchy. pp. 1–173.

- Merriman, John M. ed. 1830 in France (1975). 7 long articles by scholars.

- Newman, Edgar Leon (March 1974). "The Blouse and the Frock Coat: The Alliance of the Common People of Paris with the Liberal Leadership and the Middle Class during the Last Years of the Bourbon Restoration". The Journal of Modern History. 46 (1): 26–59. doi:10.1086/241164. S2CID 153370679.

- Pilbeam, Pamela (June 1982). "The Growth of Liberalism and the Crisis of the Bourbon Restoration, 1827–1830". The Historical Journal. 25 (2): 351–366. doi:10.1017/S0018246X00011596. S2CID 154630064.

- —— (June 1989). "The Economic Crisis of 1827–32 and the 1830 Revolution in Provincial France". The Historical Journal. 32 (2): 319–338. doi:10.1017/S0018246X00012176. S2CID 154412637.

- Pinkney, David H. (1972). The French Revolution of 1830.

- Rader, Daniel L. (1973). The Journalists and the July Revolution in France. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff. ISBN 9-0247-1552-0.

- Stewart, John Hall. The restoration era in France, 1814–1830 (1968) 223pp

- Wolf, John B. (1940). France: 1815 to the Present. pp. 1–75. OCLC 1908475. OL 6409578M.

Historiography

- Haynes, Christine. "Remembering and Forgetting the First Modern Occupations of France", Journal of Modern History 88:3 (2016): 535–571 online Archived 2020-02-25 at the Wayback Machine

- Sauvigny, G. de Bertier de (Spring 1981). "The Bourbon Restoration: One Century of French Historiography". French Historical Studies. 12 (1): 41–67. doi:10.2307/286306. JSTOR 286306.

Primary sources

- Anderson, F.M. (1904). The constitutions and other select documents illustrative of the history of France, 1789–1901. The H. W. Wilson company 1904., complete text online

- Collins, Irene, ed. Government and society in France, 1814–1848 (1971) pp 7–87. Primary sources translated into English.

- Lindsann, Olchar E. ed. Liberté, Vol. II: 1827–1847 (2012) original documents in English translation regarding politics, literature, history, philosophy, and art. online free; 430pp

- Stewart, John Hall ed. The Restoration Era in France, 1814–1830 (1968) 222pp; excerpts from 68 primary sources, plus 87pp introduction

External links

Media related to Restauration period at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Restauration period at Wikimedia Commons