Religion in Timor-Leste

Religion in Timor-Leste (2016 survey the Demographic and Health Surveys)[1]

| Religion by country |

|---|

|

|

The majority of the population of Timor-Leste is Christian, and the Catholic Church is the dominant religious institution, although it is not formally the state religion.[2] There are also small Protestant and Sunni Muslim communities.[2]

The constitution of Timor-Leste protects the freedom of religion, and representatives of the Catholic, Protestant, and Muslim communities in the country report generally good relations, although members of community groups occasionally face bureaucratic obstacles, particularly with respect to obtaining marriage and birth certificates.[3][2]

Overview

The 2015 census showed that 97.6% of the population was Catholic, 2% were Protestant, and less than 1% Muslim; Protestant denominations included the Assemblies of God, Baptists, Presbyterians, Methodists, Seventh-day Adventists, Pentecostals, Jehovah's Witnesses, and the Christian Vision Church.[2] Many citizens also retain some vestiges of animistic beliefs and practices, alongside monotheistic religion.[2]

The number of churches has grown from 100 in 1974 to over 800 in 1994,[4] with Church membership having grown considerably under Indonesian rule as Pancasila, Indonesia's state ideology, requires all citizens to believe in one God. East Timorese animist belief systems did not fit with Indonesia's constitutional monotheism, resulting in mass conversions to Christianity. Portuguese clergy were replaced with Indonesian priests and Latin and Portuguese mass was replaced by Indonesian mass.[5] Before the invasion, only 20 percent of East Timorese were Roman Catholics, and by the 1980s, 95 percent were registered as Catholics.[5][6] With over 90 percent Catholic population, Timor-Leste is currently one of the most densely Catholic countries in the world.[7]

The number of Protestants and Muslims declined significantly after September 1999 because these groups were disproportionately represented among supporters of integration with Indonesia and among the Indonesian civil servants assigned to work in the province from other parts of Indonesia, many of whom left the country in 1999.[8] The Indonesian military forces formerly stationed in the country included a significant number of Protestants, who played a major role in establishing Protestant churches in the territory.[8] Fewer than half of those congregations existed after September 1999, and many Protestants were among those who remained in West Timor.[8] In the early 2000s, the Assemblies of God was the largest and most active of the Protestant denominations.[8]

The country had a significant Muslim population during the Indonesian and Arabic rule, composed mostly of ethnic Malay immigrants from Indonesian islands.[8] There were also a few ethnic East Timorese converts to Islam, as well as a small number descended from Arab Muslims living in the country while it was under Portuguese authority.[8] The latter group was well integrated into society, but ethnic Malay Muslims at times were not.[8] Only a small number of ethnic Malay Muslims remained.[8]

Domestic and foreign missionary groups operated freely.[2]

The Constitution provides for freedom of religion; societal abuses or discrimination based on religious belief or practice occur, but they are relatively infrequent.[2]

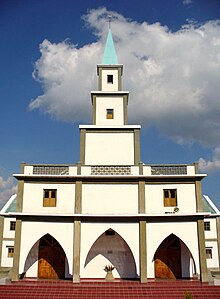

Catholicism

The Catholic Church in Timor-Leste is part of the worldwide Catholic Church, under the spiritual leadership of the Pope in Rome. In 2015, there were over 1,000,000 Catholics in Timor-Leste, a legacy of its status as a former Portuguese colony. Since its independence from Indonesia, Timor-Leste became only the second predominantly Catholic country in Asia (after the Philippines) - approximately 97.3% of the population is Catholic.[9]

The country is divided into three dioceses; Dili, Maliana and Baucau, all of which are immediately subject to the Holy See.

The Apostolic Nunciature to East Timor is Marco Sprizzi,[10] who took over from Wojciech Załuski in 2022.

Origin

In the early 16th century, Portuguese and Dutch traders made contact with Timor-Leste. Missionaries maintained a sporadic contact until 1642 when Portugal took over and maintained control until 1974, with a brief occupation by Japan during World War II.[11]

Pope John Paul II visited Timor-Leste in October 1989. Pope John Paul II had spoken out against violence in East Timor, and called for both sides to show restraint, imploring the East Timorese to "love and pray for their enemies."[12] Retired bishop Carlos Ximenes Belo is a winner of the Nobel Peace Prize along with José Ramos-Horta in 1996 for their attempts to free East Timor from Indonesia.[13] The Catholic Church remains very involved in politics, with its 2005 confrontations with the government over religious education in school and the foregoing of war crimes trials for atrocities against East Timorese by Indonesia.[14] They have also endorsed the new prime minister in his efforts to promote national reconciliation.[15] In June 2006 Catholic Relief Services received aid from the United States to help victims of months of unrest in the country.[16]

Minority religions

Islam

Islam is a minority religion in Timor-Leste. Timor-Leste's first prime minister, Mari Alkatiri, is a Muslim.[17] Islam was not traditionally practiced in Timor-Leste; much of the Muslim population are descendants of immigrants during the eras of Portuguese colonialism and Indonesian occupation.

The main mosque in Timor-Leste is the An-Nur Mosque in Dili, constructed in 1955 for the Sunni Muslim population.[18][19]

The U.S. State Department and the CIA World Factbook estimated in 2015 that Muslims made up 0.2% of the population.[20]

In 2020, the Association of Religion Data Archives reported that Sunni Muslims made up 3.6% of the population. It also reported that 0.5% of the population identified as agnostic, and that Buddhism, Chinese folk religion, Baháʼí Faith, Hinduism and Neoreligions together made up about 0.55% of the population.[21]

Hinduism

Timor-Leste was in the Indian sphere of cultural influence, known as Greater India, and was the home of some Indianized kingdoms, although Hinduism was not generally practiced in Timor-Leste. Most of the Hindu population are Balinese Hindus who migrated to Timor during the era of Indonesian occupation; following the end of the Indonesian occupation in 1999 and Timor-Leste's independence in 2002, the vast majority of Balinese Hindus left the country. Pura Girinatha, a Balinese Hindu temple, is the only Hindu place of worship in Timor-Leste.[22]

Chinese folk religion

Chinese folk religion, as well as Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism in Timor-Leste, are mainly practiced by the Hakka Chinese minority. Timor-Leste's sole Chinese temple is the Chinese Temple of Dili, founded in 1926, used by the Hakka population who profess Chinese folk religion, Buddhism, Taoism, or Confucianism, featuring shrines to Guan Yu and Guan Yin.[23][24]

Indigenous religions

Prior to the Indonesian invasion in 1975, the Austronesian people of Timor were animist polytheists with practices similar to those seen in Madagascar and Polynesia.[25] A few prominent myths remain, such as the island's conception as an aging crocodile,[26] but today practitioners of indigenous religions constitute a very small minority. Under Indonesia's religion law, Timorese had to list one of the approved monotheistic religions and a great majority listed the Catholic religion of Portugal, the Church also won Timorese over with its campaign to help them get their freedom from Indonesia.

Religious freedom

The constitution of Timor-Leste establishes the freedom of religion, and specifies that there is no state religion and that religious entities are separate from the state. Nevertheless, the constitution commends the Catholic Church for its role in securing the country's independence, and a concordat with the Holy See grants the Catholic Church certain privileges. The government routinely provides funding to the Catholic Church, and other religious organizations may apply for funding.[2]

Religious organizations are not required to register with the government, and can apply for tax-exemption status from the Ministry of Finance. Should an organization wish to run private schools or provide other community services, registration with the Ministry of Justice is required.[2]

Religious leaders have reported incidents where individual public servants have denied service to members of religious minorities, but do not consider this to be a systematic problem. The government has, however, routinely rejected birth and marriage certificates from religious organizations other than the Catholic Church. Civil certificates are the only option that religious minorities have for government recognition of marriages and births.[2]

In 2023, the country was scored 3 out of 4 for religious freedom.[27]

See also

References

- ^ "Timor-Leste: Demographic and Health Survey, 2016" (PDF). General Directorate of Statistics, Ministry of Planning and Finance & Ministry of Health. p. 35. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j US State Dept 2021 report

- ^ International Religious Freedom Report 2017 Timor-Leste, US Department of State: Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor.

- ^ Robinson, G. If you leave us here, we will die, Princeton University Press 2010, p. 72.

- ^ a b Taylor, Jean Gelman (2003). Indonesia: Peoples and Histories. Yale University Press. p. 381. ISBN 978-0-300-10518-6.

- ^ Head, Jonathan (5 April 2005). "East Timor mourns 'catalyst' Pope". BBC News.

- ^ East Timor slowly rises from the ashes ETAN 21 September 2001 Online at etan.org. Retrieved 22 February 2008

- ^ a b c d e f g h International Religious Freedom Report 2007: Timor Leste. United States Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor (14 September 2007). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Timor-Leste Demographic and Heath Survey 2016" (PDF).

- ^ Vatican News website, article dated August 22, 2022

- ^ "Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs : Asia: East Timor: Nobel-Winning Bishop Steps Down". United States Department of State. September 2005. Retrieved 18 June 2006.

- ^ "A courageous voice calling for help in East Timor". National Catholic Reporter. 11 October 1996. Archived from the original on 25 January 2013. Retrieved 18 June 2006.

- ^ "World Briefing: Asia: East Timor: Nobel-Winning Bishop Steps Down". New York Times. 27 November 2002. Retrieved 18 June 2006.

- ^ "E Timor may reconsider religious education ban". AsiaNews.it. 27 April 2005. Archived from the original on 13 November 2005. Retrieved 19 July 2006.

- ^ "Bishops encourage new premier in East Timor". Fides. 18 July 2006. Retrieved 19 July 2006.

- ^ Griffin, Elizabeth (6 June 2006). "New Supplies arrive in East Timor, more than 50,000 get relief". Catholic Relief Services. Archived from the original on 17 July 2006. Retrieved 19 July 2006.

- ^ Biographies.net website

- ^ "Sejarah Timor Leste Pernah Jadi Bagian Wilayah RI, Ini Jejak-jejak Indonesia di Bumi Lorosae - Semua Halaman - Intisari". intisari.grid.id (in Indonesian). Retrieved 8 February 2024.

- ^ "Mayoritas Agama Timor Leste adalah Katolik, Tapi Punya Masjid Bersejarah Ini, 'Rekam' Jejak Indonesia di Bumi Lorosae - Semua Halaman - Intisari". intisari.grid.id (in Indonesian). Retrieved 8 February 2024.

- ^ CIA World Factbook. Retrieved on 12 December 2015.

- ^ "The Association of Religion Data Archives | National Profiles". www.thearda.com. Retrieved 16 September 2023.

- ^ "Pastika Thanks Gusmao over Dili Temple". The Bali Times. 1 May 2009. Retrieved 8 February 2024.

- ^ "THE CHINESE TEMPLE | timor-tourism.tl". 25 November 2015. Archived from the original on 25 November 2015. Retrieved 8 February 2024.

- ^ "东帝汶:帝力关帝庙". 1 April 2018. Archived from the original on 1 April 2018. Retrieved 8 February 2024.

- ^ Lee Haring, Stars and Keys: Folktales and Creolization in the Indian Ocean, Indiana University Press, 19/07/2007

- ^ Wise, Amanda (2006), Exile and Return Among the East Timorese, Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 211–218, ISBN 0-8122-3909-1

- ^ Freedom House website, retrieved 2023-08-08

- United States Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor. East Timor: International Religious Freedom Report 2007. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.