Ransom

| Part of a series on |

| Kidnapping |

|---|

|

| Types |

| By country |

Ransom is the practice of holding a prisoner or item to extort money or property to secure their release, or the sum of money involved in such a practice.

When ransom means "payment", the word comes via Old French rançon from Latin redemptio, 'buying back';[1] compare "redemption".

Ransom cases

Julius Caesar was captured by pirates near the island of Pharmacusa, and held until someone paid 50 talents to free him.[2]

In Europe during the Middle Ages, ransom became an important custom of chivalric warfare. An important knight, especially nobility or royalty, was worth a significant sum of money if captured, but nothing if he was killed. For this reason, the practice of ransom contributed to the development of heraldry, which allowed knights to advertise their identities, and by implication their ransom value, and made them less likely to be killed out of hand. Examples include Richard the Lion Heart and Bertrand du Guesclin.

In 1532, Francisco Pizarro was paid a ransom amounting to a roomful of gold by the Inca Empire before having their leader Atahualpa, his victim, executed in a rigged trial. The ransom payment received by Pizarro is recognized as the largest ever paid to a single individual, probably over $2 billion in today's economic markets.[citation needed]

Modern

The abduction of Charley Ross on July 1, 1874, is considered to be the first American kidnapping for ransom.

East Germany, which built the Inner German border to stop emigration, practised ransom with people. East German citizens could emigrate through the semi-secret route of being ransomed by the West German government in a process termed Freikauf (literally the buying of freedom).[3] Between 1964 and 1989, 33,755 political prisoners were ransomed. West Germany paid over 3.4 billion DM—nearly $2.3 billion at 1990 prices—in goods and hard currency.[4] Those ransomed were valued on a sliding scale, ranging from around 1,875 DM for a worker to around 11,250 DM for a physician. For a while, payments were made in kind using goods that were in short supply in East Germany, such as oranges, bananas, coffee, and medical drugs. The average prisoner was worth around 4,000 DM worth of goods.[5]

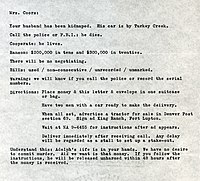

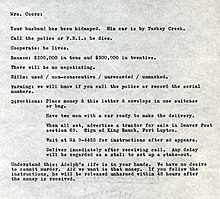

Ransom notes

A request for ransom may be conveyed to the target of the effort by a ransom note, a written document outlining the demands of the kidnappers. In some instances, however, the note itself can be used as forensic evidence to discover the identities of unknown kidnappers,[6] or to convict them at trial. For example, if a ransom note contains misspellings, a suspect might be asked to write a sample of text to determine if they make the same spelling errors.[6]

Following cases where forensic evidence pinpointed particular typewriters to typed ransom notes, kidnappers started to use pre-printed words assembled from different newspapers. In popular culture, ransom notes are often depicted as being made from words in different typefaces clipped from different sources (typically newspapers), in order to disguise the handwriting of the kidnapper,[7] leading to the phrase ransom note effect being used to describe documents containing jarringly mixed fonts. An early use of this technique in film is in the 1952 film The Atomic City.

In some instances, a person may forge a ransom note in order to falsely collect a ransom despite not having an actual connection to the kidnapper.[8] On other occasions, a ransom note has been used as a ploy to convince family members that a person is being held for ransom when that person has actually left of their own volition or was already dead before the note was sent.

Variations

There were numerous instances in which towns paid to avoid being plundered, an example being Salzburg which, under Paris Lodron, paid a ransom to Bavaria to prevent its being sacked during the Thirty Years' War. As late as the Peninsular War (1808–14), it was the belief of the English soldiers that a town taken by storm was liable to sack for three days, and they acted on their conviction at Ciudad Rodrigo, Badajoz and San Sebastian.

In the early 18th century, the custom was that the captain of a captured vessel gave a bond or "ransom bill", leaving one of his crew as a hostage or "ransomer" in the hands of the captor. Frequent mention is made of the taking of French privateers which had in them ten or a dozen ransomers. The owner could be sued on his bond. Payment of ransom was banned by the Parliament of Great Britain in 1782[9] although this was repealed in 1864.[10] It was generally allowed by other nations.

In the Russo-Japanese War, though no mention was made of ransom, the contributions levied by invading armies might still be accurately described by the name.

Although ransom is usually demanded only after the kidnapping of a person, it is not unheard of for thieves to demand ransom for the return of an inanimate object or body part. In 1987, thieves broke into the tomb of Argentinian president Juan Perón and then severed and stole his hands; they later demanded $8 million US for their return. The ransom was not paid.[11]

The practice of towing vehicles and charging towing fees for the vehicles' release is often dysphemised as "ransoming" by opponents of towing. In Scotland, booting vehicles on private property is outlawed as extortion. In England, the clamping of vehicles is theoretically the Common law offence of "holding property to ransom".

Warring international military groups have demanded ransom for any personnel they can capture from their opposition or their opposition's supporters. Ransom paid to these groups can encourage more hostage-taking.[12]

See also

References

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 22 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 895.

- ^ Plutarch, "The Life of Julius Caesar" in The Parallel Lives, Loeb Classical Library edition, 1919, Vol. VII, p. 445. The pirates originally demanded 20 talents, but Caesar felt he was worth more. After he was freed he came back, captured the pirates, took their money and eventually crucified all of them, a fate he had threatened the incredulous pirates with during his captivity.

- ^ Buckley (2004), p. 104

- ^ Hertle (2007), p. 117.

- ^ Buschschluter (1981-10-11).

- ^ a b D. P. Lyle, Howdunit Forensics (2008), p. 378.

- ^ Walter S. Mossberg, The Wall Street Journal Book of Personal Technology (1995), p. 92.

- ^ John Townsend, Fakes and Forgeries (2005), p. 13.

- ^ Ransom Act 1782 (22 Geo. 3. c. 25)

- ^ Naval Prize Acts Repeal Act 1864 (27 & 28 Vict. c. 23)

- ^ "Peron Hands: Police Find Trail Elusive." The New York Times, September 6, 1987. Accessed October 16, 2009.

- ^ "Paying ransom for journalists encourages more kidnapping" The Washington Post, September 22, 2014