Dúnedain

| Dúnedain | |

|---|---|

| In-universe information | |

| Other name(s) | Men of the West, Men of Westernesse |

| Creation date | S.A. 1 |

| Home world | Middle-earth |

| Capital | Armenelos, Annúminas, Fornost Erain, Osgiliath, Minas Tirith |

| Base of operations | Númenor, Arnor and Gondor |

| Language | Adûnaic, Westron, Sindarin, Quenya |

| Leader | Kings of the Dúnedain |

In J. R. R. Tolkien's Middle-earth writings, the Dúnedain (/ˈduːnɛdaɪn/; singular: Dúnadan, "Man of the West") were a race of Men, also known as the Númenóreans or Men of Westernesse (translated from the Sindarin term). Those who survived the sinking of their island kingdom and came to Middle-earth, led by Elendil and his sons, Isildur and Anárion, settled in Arnor and Gondor.

After the Downfall of Númenor, the name Dúnedain was reserved to Númenóreans who were friendly to the Elves: hostile survivors of the Downfall were called Black Númenóreans.

The Rangers were two secretive, independent groups of Dúnedain of the North (Arnor) and South (Ithilien, in Gondor) in the Third Age. Like their Númenórean ancestors, they had qualities like those of the Elves, with keen senses and the ability to understand the language of birds and beasts.[1] They were trackers and hardy warriors who defended their respective areas from evil forces.

History

Númenóreans

The Dúnedain were descended from the Edain, the Elf-friends: the few tribes of Men of the First Age who sided with the Noldorin Elves in Beleriand. The original leader of the Edain was Bëor the Old, a vassal of the Elf lord Finrod. His people settled in Eldar lands. At the beginning of the Second Age, the Valar gave the Edain Númenor to live on. Númenor was an island-continent located far to the west of Middle-earth, and hence these Edain came to be called Dúnedain: Edain of the West. Their first King was Lord Elros, a half-Elf, and also a descendant of Bëor.[3]

These first Dúnedain are the Númenóreans. They became a great civilization, and began maritime pursuits for exploration, trade and power. Some returned to Middle-earth, creating fortress-cities along its western coasts, dominating the lesser men of these areas. In time the Númenóreans split into two rival factions: the Faithful, remaining loyal to the Valar and Elves, and the King's Men, who were eventually seduced by the Dark Lord, Sauron.[3]

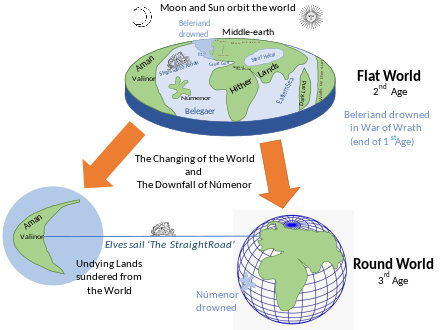

Ultimately Númenor was drowned in a great cataclysm,[2] but a remnant of the Faithful escaped in nine ships. Led by Elendil, they established the Dúnedain kingdoms of Arnor and Gondor in Middle-earth.[T 1] There is a suggestion, voiced by Faramir, son of the Steward of Gondor, that these descendants of Númenóreans are higher than other Men; but his speech on the matter has been described as "arrogant" and as such not necessarily to be taken literally.[3]

Sauron's spirit also escaped, and fled back to Middle-earth, where he again raised mighty armies to challenge Gondor and Arnor. With the aid of Gil-galad and the Elves, Sauron was defeated, and the Third Age began. Sauron vanished into the East for many centuries, and Gondor and Arnor prospered. As Sauron re-formed and gathered strength, a series of deadly plagues came from the East. These struck harder in the North than the South, causing a population decline in Arnor. Arnor fractured into three kingdoms. The chief of the Nine Ringwraiths, the Witch-king of Angmar, assaulted and destroyed the divided Northern Dúnedain kingdoms from his mountain stronghold of Carn Dûm. After their fall, a remnant of the northern Dúnedain became the Rangers of the North, doing what they could to keep the peace in the near-empty lands of their Fathers. The surviving Dúnedain of Arnor retreated to the Angle south of Rivendell, while smaller populations settled in far western Eriador. The fragmentation of the kingdoms has been compared to that of the early Frankish kingdoms.[3]

Over the centuries, many southern Dúnedain of Gondor intermarried with other Men. Their lifespan became shorter with each generation. Eventually, even the Kings of Gondor married non-Dúnedain women occasionally. Only in regions such as Dol Amroth did their bloodline remain pure. In the Fourth Age, the Dúnedain of Gondor and Arnor were reunited under King Aragorn II Elessar (the Dúnadan), a direct descendant of Elros and Elendil. He married Arwen, reintroducing Elf-blood into his family line.[3] In addition to the Faithful, Men in the South manned Númenórean garrisons at places like Umbar. Many of these folk were turned toward evil by Sauron's teachings, and became known as the Black Númenóreans.[3]

The Dúnedain among the Half-elven

| Half-elven family tree[T 2][T 3] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Rangers of the North

The Rangers were grim in life, appearance, and dress, choosing to wear rustic green and brown. The Rangers of the Grey Company were dressed in dark grey cloaks and openly wore a silver brooch shaped like a pointed star during the War of the Ring. They rode rough-haired, sturdy horses, were helmeted and carried shields. Their weapons included spears and bows. They spoke Sindarin in preference to the Common Speech. They were led by Chieftains, the heirs and direct descendants of Elendil, the first King of Arnor and Gondor; Elendil in turn was descended from Kings of Númenor and the Elf-kings of the First Age.

During the War of the Ring, the Rangers of the North were led by Aragorn, but the northern Dúnedain were a dwindling folk: when Halbarad gathered as many Rangers as he could and led them south to Aragorn's aid, he could only muster thirty men to form the Grey Company.

Aranarth would have been King of Arnor at the death of his father Arvedui. When Aranarth was still a youth, the Witch-king of Angmar destroyed the Northern Kingdom, overrunning Fornost. Most of the people, including Aranarth, fled to Lindon, but King Arvedui went north to the Ice-Bay of Forochel. At Aranarth's urging, Círdan sent a ship to rescue Arvedui, but it sank with Arvedui on board. Aranarth was then by right King of Arnor, but since the Kingdom had been destroyed, he did not claim the title. Instead, he rode with the army of Gondor under Eärnur and saw the destruction of Angmar. Aranarth's people became known as the Rangers of the North, and he was the first of their Chieftains. The Rangers defended Arnor from the remnants of Angmar's evil, and so began the Watchful Peace. Aranarth's successors were raised in Rivendell by Elrond while their fathers lived in the wild; each was given a name with the Kingly prefix of Ar(a)-, to signify his right to the Kingship of Arnor.[T 4]

Aranarth's line descended father to son to Aragorn II, a protagonist in The Lord of the Rings. His father Arathorn was killed two years after his birth. He assumed lordship of the Dúnedain of Arnor when he came of age. He was a member of the Fellowship of the Ring and fought in the War of the Ring. He was crowned King Elessar of the Reunited Kingdom of Gondor and Arnor. That same year, Aragorn married Arwen, daughter of Elrond. Their son, Eldarion, succeeded him as king. In Eldarion the two bloodlines of the Half-elven were reunited, Arwen being the daughter of the immortal Elrond and Aragorn the 60th-generation descendant of Elrond's mortal twin brother, Elros.

Rangers of Ithilien

The Rangers of Ithilien, also known as the Rangers of the South and Rangers of Gondor, were an elite group who scouted in and guarded the land of Ithilien. They were formed late in the Third Age by a decree of the Ruling Steward of Gondor, for Ithilien was subject to attack from Mordor and Minas Morgul. One of their chief bases was Henneth Annûn, the Window of the Sunset. These were descendants of those who lived in Ithilien before it was overrun. Like the Rangers of the North, they spoke Sindarin as opposed to the Common Speech. They wore camouflaging green and brown clothing, secretly crossing the Anduin to assault the Enemy. They were skilled with swords and bows or spears.

Analysis

The Rangers of Arnor and their lost realm have been compared to medieval tribes and societies of the real world. Like the Franks after the fall of the Western Roman Empire or the Christianized Anglo-Saxons, the northern Rangers inhabit a "romanized nobility" and keep protecting the borders of the "realms of good" while Gondor in the south is decaying and finally arrives on the verge of destruction.[5] This protection of the weak from evil by Aragorn and his rangers has been identified as an inherently Christian motif in Tolkien's design of his legendarium.[6]

The Rangers have been compared to the 'Spoonbills' in John Buchan's 1923 novel Midwinter, while the Ranger-like 'Lakewalkers' in the 2006–2019 The Sharing Knife series by Lois McMaster Bujold have been seen as part of a deliberate commentary on Middle-earth.[7][8]

Thomas Kullmann and Dirk Siepmann comment that Aragorn's pathfinding lifestyle and style of speech resembles that of the ranger Natty Bumppo in James Fenimore Cooper's 1823–1841 Leatherstocking Tales, suggesting that Aragorn's "If I read the sign back yonder rightly" could easily have been spoken by Bumppo.[4] On the other hand, they write, Aragorn's awareness of "a historical and mythological past", and his continuity with those, is "emphatically lacking" in Cooper's writings.[4]

In adaptations

In film

With the exception of Aragorn, the Rangers of the North are virtually omitted in Peter Jackson's The Lord of the Rings film trilogy, save for a few mentions in the extended cuts. Arnor is mentioned only in one line in the extended edition of The Two Towers, when Aragorn explains to Éowyn that he is a "Dúnedain Ranger", of whom few remain because "the North-kingdom was destroyed". There is however an original Ranger of Ithilien named Madril, played by John Bach.[9] He serves as Faramir's lieutenant. He helps defend Osgiliath, but is fatally injured and is eventually killed by Gothmog by a spear-thrust. New Zealand actor Alistair Browning played another Ranger of Ithilien, Damrod.[10]

The Rangers are shown as a village community in the 2009 fan film Born of Hope. The film centres on the relationship of Arathorn and Gilraen, and the infancy of their son Aragorn.[11]

In games

In the game The Lord of the Rings: The Third Age there is an original Ranger character called Elegost.[12] In The Lord of the Rings: The Battle for Middle-earth II, there are both Northern Dúnedain and Ithilien Rangers.[13] Halbarad is featured in The Lord of the Rings Trading Card Game,[14] and, together with his fellow Rangers, in The Lord of the Rings Strategy Battle Game.[15] Rangers of the North appear in The Lord of the Rings Online, with Ranger camps and named characters such as Calenglad.[16] Tolkien's Rangers are the primary inspiration for the Dungeons & Dragons character class called "Ranger".[17]

References

Primary

- ^ Tolkien 1955, Appendix A, I (i) "Númenor"

- ^ Tolkien 1977, "Of the Rings of Power and the Third Age": Family Trees I and II: "The house of Finwë and the Noldorin descent of Elrond and Elros", and "The descendants of Olwë and Elwë"

- ^ Tolkien 1955, Appendix A: Annals of the Kings and Rulers, I The Númenórean Kings

- ^ Tolkien 1955, Appendix A, I (ii) "The Realms in Exile"

Secondary

- ^ Chance, Jane (2001). Lord of the Rings: The Mythology of Power. University Press of Kentucky. p. 39.

- ^ a b Shippey, Tom (2005) [1982]. The Road to Middle-Earth (Third ed.). The Lost Straight Road: HarperCollins. pp. 324–328. ISBN 978-0261102750.

- ^ a b c d e f Straubhaar, Sandra Ballif (2013) [2007]. "Men, Middle-earth". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 414–417. ISBN 978-1-135-88034-7.

- ^ a b c Kullmann & Siepmann 2021, p. 269.

- ^ Birzer, Bradley J. (2014). J. R. R. Tolkien's Sanctifying Myth: Understanding Middle-earth. Open Road Media. ISBN 978-1-49764-891-3.

- ^ Rutledge, Fleming (2004). The Battle for Middle-earth: Tolkien's Divine Design in The Lord of the Rings. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-80282-497-4.

- ^ Hooker, Mark T. (2011). "Reading John Buchan in Search of Tolkien". In Fisher, Jason (ed.). Tolkien and the Study of His Sources: Critical Essays. McFarland. p. 165. ISBN 978-0-78648-728-8.

- ^ James, Edward (2015). Lois McMaster Bujold. University of Illinois Press. pp. 71–72. ISBN 978-0-25209-737-9.

- ^ Mathijs, Ernest; Pomerance, Murray, eds. (2006). "Dramatis personae". From Hobbits to Hollywood: Essays on Peter Jackson's 'Lord of the Rings'. Editions Rodopi. pp. ix–xii. ISBN 90-420-1682-5.

- ^ "Alistair Browning - Actor Profile & Biography". Archived from the original on 3 June 2019. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- ^ Martin, Nicole (27 October 2008). "Orcs are back in Lord of the Rings-inspired Born of Hope". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on October 29, 2008. Retrieved 13 June 2016.

- ^ "The Lord of the Rings, The Third Age Player Reviews". The Gamer's Temple. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- ^ "The Lord of the Rings, The Battle for Middle-earth II Walkthrough". GameSpot. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- ^ "Lord of the Rings: Expanded Middle Earth - Halbarad Deluxe Draft Box (54 cards)". InMint. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- ^ Harman, Joshua. "Where do I find...? Characters" (PDF). DC Hobbit League. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- ^ "Rangers of the North Quest". GamePressure.com. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- ^ Tresca, Michael J. (2011). The Evolution of Fantasy Role-Playing Games. McFarland & Company. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-7864-5895-0.

Sources

- Kullmann, Thomas; Siepmann, Dirk (2021). Tolkien as a Literary Artist. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-3-030-69298-8.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1955). The Return of the King. The Lord of the Rings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 519647821.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1977). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The Silmarillion. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-25730-2.