Railway post office

In Canada and the United States, a railway post office, commonly abbreviated as RPO, was a railroad car that was normally operated in passenger service and used specifically for staff to sort mail en route, in order to speed delivery. The RPO was staffed by highly trained Railway Mail Service postal clerks, and was off-limits to the passengers on the train.

From the middle of the 19th century, many American railroads earned substantial revenues through contracts with the U.S. Post Office Department (USPOD) to carry mail aboard high-speed passenger trains. The Railway Mail Service enforced various standardized designs on RPOs. A number of railway companies maintained nominally unprofitable passenger routes, having found that their financial losses from moving people were more than offset by transporting the mail on such passenger routes.

History

The world's first official carriage of mail by rail was by the United Kingdom's General Post Office in November 1830, using adapted railway carriages on the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. Sorting of mail en-route first occurred in the United Kingdom with the introduction of the travelling post office in 1838 on the Grand Junction Railway,[1][2] following the introduction of the Railways (Conveyance of Mails) Act 1838.

In the United States, some references suggest that the first shipment of mail carried on a train (sorted at the endpoints and carried in a bag on the train with other baggage) occurred in 1831 on the South Carolina Rail Road. Other sources state that the first official contract to regularly carry mail on a train was made with the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad in either 1834 or 1835. The United States Congress officially designated all railroads as official postal routes on July 7, 1838.[2] Similar services were introduced on Canadian railroads in 1859.[3]

The railway post office was introduced in the United States on July 28, 1862, using converted baggage cars on the Hannibal and St. Joseph Railroad (which also delivered the first letter to the Pony Express). Purpose-built Railway Post Office (RPO) cars entered service on this line a few weeks after the service was initiated. They were used by staff to separate mail for connection with a westbound stagecoach departing soon after the train's arrival at St. Joseph. This service lasted approximately one year.[4]

The first permanent Railway Post Office route was established on August 28, 1864, between Chicago, Illinois, and Clinton, Iowa.[5] This service is distinguished from the 1862 operation because mail was sorted to and received from each post office along the route, as well as major post offices beyond the route's end-points.

George B. Armstrong, assistant postmaster at Chicago, originally came up with the idea of having mail processed and distributed while the mail was on board, en route in mail cars. With the assistance of Schuyler Colfax, Speaker of the House at the time, and A. N. Zevely, Third Assistant Postmaster General, Armstrong was authorized to test his ideas.[6]

In 1869, the Railway Mail Service (RMS), headed by George B. Armstrong, was officially inaugurated to handle the transportation and sorting of mail aboard trains. Armstrong was promoted from a supervisory position in the Chicago post office following his experiments in 1864 with a converted route agent's car on runs between Chicago and Clinton, Iowa.[7]

RPO car interiors, which at first consisted of solid wood furniture and fixtures, were soon redesigned to support their new purpose. In 1879, an RMS employee named Charles R. Harrison developed a new set of fixtures that soon gained widespread use. Harrison's design consisted of hinged, cast-iron fixtures that could be unfolded and set up in a number of configurations to hold mail pouches, racks and a sorting table as needed for specific routes. The fixtures were also designed so they could be folded away completely to provide a wholly open space to carry general baggage and express shipments as needed by the railroads. Harrison followed through with manufacturing his design at a factory he opened in Fond du Lac, Wisconsin in 1881.[8]

The July 1, 1862, Pacific Railroad Act signed by President Lincoln established government funding for the construction of a railroad from the Missouri River to the Pacific Ocean in order to open a main line mail route across the western frontier. The act was officially entitled "AN ACT to aid in the construction of a railroad and telegraph line from the Missouri river to the Pacific Ocean, and to secure to the government the use of the same for postal, military, and other purposes". The Act authorized government-funded railroad mail routes across the American continent.[9]

By the 1880s, railway post office routes were operating on the vast majority of passenger trains in the United States. A complex network of interconnected routes allowed mail to be transported and delivered in a remarkably short time. As many as a dozen clerks might work in a single RPO car, although fewer would be required if part of the car was used for transport of previously sorted mail or (often in a separate compartment) express and baggage.[10]

Railway mail clerks were subjected to stringent training and regular testing of details regarding their handling of the mail. On a given RPO route, each clerk was expected to know not only the post offices and rail junctions along the route, but also specific local delivery details within each of the larger cities served by the route. Periodic testing demanded both accuracy and speed in sorting mail, and a clerk scoring only 96% accuracy would likely receive a warning from the Railway Mail Service division superintendent. Interurban and Streetcar systems were also known to operate RPOs. The Boston Elevated Railway car was noted for making circuits of the city to pick up mail.[11]

In the United States, RPO cars (also known as mail cars or postal cars) were equipped and staffed to handle most back-end postal processing functions. First class mail, magazines and newspapers were all sorted, cancelled when necessary, and dispatched to post offices in towns along the route. Registered mail was also handled. The foreman in charge was required to carry a regulation pistol while on duty to discourage theft of the mail.

Standardization

Because of the physical and mental demands placed on RPO clerks, the Railway Mail Service pushed the adoption of standardized floor plans and fixtures for all RPO cars, with the first plans published in 1885. The RMS also pressed for improved lighting fixtures to help the clerks see the addresses on the mail they sorted, first by improving the reflectors in the 1880s, then calling for discontinuance of oil lamps in the 1890s and the first experiments with electric lighting in 1912. Clerks' safety was also of great concern to the RMS, with the first comprehensive statistics on work-related injuries published in 1877.[12]

Through the second half of the 19th century, most RPO cars were painted in a somewhat uniform color scheme regardless of the railroad that owned or operated them. Most were painted white with trim in either buff, red or blue, which made the cars stand out from the other cars. By the 1890s, this practice had waned as railroads painted their RPO cars to match the rest of their passenger equipment. One RPO car that was displayed at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago is one of the last known examples of the early white color scheme.[13]

As the development of passenger cars progressed, so too did the development of RPO cars. The first plans for RPO car designs were based on light baggage car frames and bodies, which sometimes resulted in catastrophe for RMS employees when the trains were involved in accidents. From 1900 to 1906 some 70 workers were killed in train wrecks while on duty in the RPOs, leading to demands for stronger steel cars.[14] The RMS developed its first standards for car design in 1891 to address some of these issues.[15]

In 1912, the Railway Mail Service developed a set of strength requirements for new cars in an effort to push the car building companies into using steel for the cars' major structural components and underframes. The core of the requirements was that each car should be able to withstand a buffer force of at least 400,000 pounds. This requirement was doubled to 800,000 pounds in a 1938 revision of the standards. The requirements were again strengthened in 1945 with specifications that precluded the use of aluminium for framing and major structural components. The 1945 revisions also included a requirement for end posts to prevent telescoping in the event of a collision. Railway car manufacturers adopted these requirements and carried them through to all other models of passenger cars that they built.[16]

The 800,000-lb buffer load and end post requirements were later adopted by the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) for all passenger MU locomotives as of April 1, 1956.[17] They were extended to all passenger cars and locomotives in 1999 by the USDOT.[18]

An interesting feature of most RPO cars was a hook that could be used to snatch a leather or canvas pouch of outgoing mail hanging on a track-side mail crane at smaller towns where the train did not stop. The first US patent for such a device (U.S. patent 61,584) was awarded to L. F. Ward of Elyria, Ohio, on January 29, 1867.[19] This was about a year after apparatus for picking up and setting down mailbags without stopping was installed for equivalent UK TPOs at Slough and Maidenhead, having first been patented in UK in 1838 by Nathaniel Worsdell.

With the train often operating at 70 mph or more, a postal clerk would have a pouch of mail ready to be dispatched as the train passed the station. In a co-ordinated movement, the catcher arm was swung out to catch the hanging mail pouch while the clerk stood in the open doorway. The mail pouch had a strap around the middle, and the strap was tightened in preparation for pickup with an approximately equivalent weight of mail in either end of the pouch to prevent the heavier end from pulling the lighter end off the catcher arm. As the inbound pouch slammed into the catcher arm, the clerk kicked the outbound mail pouch out of the car, making certain to kick it far enough that it was not sucked back under the train. Outbound pouches of first class mail were sealed with a locked strap for security. Larger sacks with optional provisions for locking were used for newspapers, magazines, and parcel post. An employee of the local post office would retrieve the pouches and sacks and deliver them to the post office.[10]

In the 1950s the Budd Company offered two versions of its self-propelled diesel RDC with RPO: the RDC-3 combine and the RDC-4 (a baggage/mail/express only unit). These models were purchased by the New York Central, Boston & Maine, New Haven Railroad, Rock Island, Pacific Great Eastern, Northern Pacific, Canadian Pacific Railway, Canadian National and Minneapolis & St. Louis.[20]

- Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad #1923, a heavyweight RPO preserved at the Illinois Railway Museum.

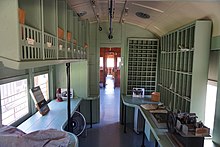

- The interior of an RPO on display at the National Railroad Museum in Green Bay, Wisconsin.

- A close-up view of the mail hook on CB&Q #1923.

- A view of the mail hook on GN #42, along with a track-side mail crane complete with mail bag.

- Belfast & Moosehead Lake RR #15 RPO, Belfast, ME 1947

- Former Richmond, Fredericksburg and Potomac Railroad post office (1916), on display at RF&P Park, Glen Allen, VA.

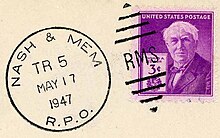

Cancellation stamps

Most RPO cars had a mail slot on the side of the car, so that mail could actually be deposited in the car, much like using the corner mail box, while the train was stopped at a station. Those desiring the fastest delivery would bring their letters to the train station for dispatch on the RPO, knowing that overnight delivery would be virtually assured. The mail handled in this manner received a cancellation just as if it had been mailed at a local post office, with the cancel giving the train number, endpoint cities of the RPO route, the date, and RMS Railway Mail Service or PTS Postal Transportation Service between the killer bars. Collecting such cancellations is a pastime of many philatelists and postal history researchers.

The Railway Mail Service organization within the Post Office Department existed between 1864 and September 30, 1948. It was renamed the Postal Transportation Service on October 1, 1948, and existed until 1960. After 1960, the management of railway post office routes as well as Highway Post Office routes, Air Mail Facility, terminal railway post offices, and transfer offices, were shifted to the Bureau of Transportation.

Decline and withdrawal

At their height, RPO cars were used on over 9,000 train routes covering more than 200,000 route miles in North America. While the majority of this service consisted of one or more cars at the head end of passenger trains, many railways operated solid mail trains between major cities; these solid mail trains would often carry 300 tons of mail daily.[2][A]

After 1948, the railway post office network began its decline although it remained the principal intercity mail transportation and distribution function within the Post Office Department (POD). There were 794 RPO lines operating over 161,000 miles of railroad in that year. Only 262 RPO routes were still operating by January 1, 1962. In 1942, the POD began experimenting with a highway version of the RPO to serve the same purposes along routes where passenger train service was not available. These highway post office (HPO) vehicles were initially intended to supplement RPO service, but in the 1950s and 1960s, HPOs often replaced railway post office cars after passenger train service was discontinued. The last interurban RPO service was operated by Pacific Electric Railway on its route between Los Angeles and San Bernardino, California.[22]

When the post office made a controversial policy change to process mail in large regional "sectional centers," mail was now sorted by large machines, not by people, and the remaining railway post office routes, along with all highway post office routes, were phased out of service. In September 1967 the POD cancelled all "mail by rail" contracts, electing to move all first class mail via air and other classes by road (truck) transport. This announcement had a devastating effect on passenger train revenues; the Santa Fe, for example, lost $35 million (US) in annual business, and led directly to the ending of many passenger rail routes.

After 113 years of railway post office operation, the last surviving railway post office running on rails between New York and Washington, D.C. was discontinued on June 30, 1977. The last route with a railway post office title was actually a boat run that lasted a year longer. This boat railway post office was the Lake Winnipesaukee RPO operating between The Weirs, New Hampshire, and Bear Island on Lake Winnipesaukee. The final date it operated with a postmark was September 30, 1978.

Preservation

Many RPO cars have been preserved in railroad museums across North America; some of the cars are kept in operational condition. In 1933, Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad rebuilt one of its baggage cars into a replica of the first RPOs that were used on the Hannibal and St. Joseph Railroad in 1862. The railroad displayed the car in several cities along the railroad; it now resides at the Patee House Museum in St. Joseph, Missouri.[5]

The Minnesota Transportation Museum (MTM) maintains Northern Pacific #1102, a 1914 Mail RPO, that is classed as a "combine" car, having sections for the RPO, Railway Express Agency and twenty seats for paying passengers. Currently, it is the only Railway Post Office car known to be operational and currently certified for operation on commercial rail. The Osceola and St Croix Valley Railway (division of MTM/reporting mark MNTX) operates the car as part of its tour line, actually "catching the mail on the fly" as a part of its regular runs.[citation needed]

As part of the 40th anniversary of the end of RPO service, Minnesota Transportation Museum will be placing #1102 on display at Saint Paul Union Depot as part of its "Last Mail Train" for National Train Day, 6 May 2017. At the end of the day, Great Northern 400, Northern Pacific Railway RPO #1102 and two coaches will be departing Union Depot as Train #1 bound for Osceola, Wisconsin. It will be hauling commemorative envelopes and cards to be sent all across the United States, following which it will operate in regular service as part of the Museum operations out of Osceola, WI.[citation needed]

Steamtown National Historic Site in Scranton, PA has RPO car #1100, Louisville & Nashville, on display. It is an all-steel car built in 1914 by the American Car and Foundry Company. The Oil Creek and Titusville Railroad operates a post office car and all mail posted there gets an official USPS OC&T postmark.[23]

See also

- Boat railway post office

- Catcher pouch

- Mail bag

- Mail hook

- Mail pouch

- Mail sack

- Mobile post office

- Owney (dog)

- Post Office sorting van

- Railway mail service library

- SNCF TGV La Poste French Post Office dedicated TGV sets

- Terminal railway post office

- Transfer office

- Travelling post office — the term for cars in British use that served similar functions.

Notes

- ^ As the United States Postal Service undergoes its fiscal crisis in the second decade of the 21st Century, it is well to note that these are not entirely new problems. A national pick up and delivery system to remote and small locales is a fiscally challenging model. "A Congressional Investigation of the United States Post Office Department in 1900 disclosed that postal expenditures were not and, in some cases, could not be apportioned to revenues. A remarkable anomaly in Maine, at the intersection of mail bags and a printing press, provided, at the time, a basis for costing questions of policy and regulation and, for us now, an understanding of the postal commons in its Golden Age." DeBlois, Diane; Harris, Robert Dalton. "It's in the Bag" – The Shape of Turn-of-the-Century Mail" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 15, 2013. Retrieved August 16, 2012.

References

Citations

- ^ Johnson 1995.

- ^ a b c White, p 472.

- ^ White, p 473

- ^ White, p 475.

- ^ a b "First as well as fast". Classic Trains. Vol. 7, no. 3. Fall 2006. p. 27. ISSN 1527-0718.

- ^ "Mail Post Office". www.catskillarchive.com.

- ^ White, pp 475–476.

- ^ White, pp 481–482.

- ^ "Pacific Railroad Act – Transcontinental Railroad and Land Grants". www.cprr.org.

- ^ a b Mosher, Willard C. (1982). "Railway Postal Service – Revisted". The 470 (March 1982). The 470 Railroad Club: 11 & 12.

- ^ Trolley Car Treasury' by Frank Rowsome Jr. McGraw-Hill, New York, 1956 -Library of Congress 56-11054

- ^ White, p 482.

- ^ White, p 480.

- '^ Daily Mirror, March 16, 1906, p6, Last night's news

- ^ White, p 483.

- ^ White, p 190.

- ^ 49 CFR Part 229.141, 2015 edition (10-1-2015) https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CFR-2015-title49-vol4/xml/CFR-2015-title49-vol4-sec229-141.xml

- ^ 49 CFR Part 238, Subpart C, U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Railroad Administration, 2015 edition https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CFR-2015-title49-vol4/xml/CFR-2015-title49-vol4-part238-subpartC.xml

- ^ White, p 476

- ^ Budd Company Red Lion Plant Order List, Philadelphia Chapter of the National Railway Historical Society. http://www.trainweb.org/phillynrhs/BuddCarOrders.html

- ^ Nashville, Chattanooga & St. Louis Railway: The Dixie Line by Charles B. Castner, Jr. page 92 ISBN 0-911868-87-9

- ^ Demoro, Harre W. (1986). California's Electric Railways. Glendale, California: Interurban Press. p. 19. ISBN 0-916374-74-2.

- ^ "Oil Creek and Titusville Railroad – Titusville Pennsylvania". octrr.org.

Sources

- Johnson, Peter. (1995) Mail by Rail – The History of the TPO & Post Office Railway, Ian Allan Publishing, London. ISBN 0-7110-2385-9

- White, John H. (1978). The American Railroad Passenger Car. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0801819652. OCLC 2798188.

Further reading

- Bergman, Edwin B. (1980) 29 Years to Oblivion, The Last Years of Railway Mail Service in the United States, Mobile Post Office Society, Omaha, Nebraska.

- Crissy, Forrest (December 1902). "The Traveling Post-Office". The World's Work: A History of Our Time. V: 2873–2880. Retrieved 2009-07-10.

- Culbreth, Ken (2007). The railway mail clerk and the highway post office: when the mail really worked: the story of the postal service's elite. Victoria, B.C, Canada: Trafford Publishing. ISBN 9781412202275.

- Cushing, Marshall (1893). The Story of Our Post Office: The Greatest Government Department in all its Phases. Boston, Massachusetts: A.M. Thayer & Co. at Internet archive

- Long, Bryant Alden (1951). Mail by Rail. New York: Simmons-Boardman Publishing Corporation.

- Melius, Louis (1917). The American postal service: history of the postal service from the earliest times. The American system described with full details of operation. Washington, D.C.: National Capital Press. Retrieved August 15, 2012. at Internet Archive

- National Postal Transport Association. (1956) MAIL IN MOTION, Railway Mail Service Library, Boyce, Virginia. Portion available as a video clip at [1]

- Romanski, Fred J. The Fast Mail, History of the Railway Mail Service, Prologue Vol. 37 No. 3, Fall 2005, College Park, Maryland.

- Pennypacker, Bert The Evolution of Railway Mail, National Railway Bulletin Vol. 60 No. 2, 1995, Philadelphia.

- Towle, Charles L.; Meyer, Henry A. (1958). "Railroad Postmarks of the U.S.], 1861–1886". Archived from the original on November 18, 2011. Retrieved August 21, 2012.

- U.S. Post Office Department. (1956) MEN AND MAIL IN TRANSIT, Railway Mail Service Library, Boyce, Virginia. Portion available as a video clip at [2]

- Wilking, Clarence R. (1985). The Railway Mail Service United States Mail Railway Post Office (MSWord). Marietta, OH: Railway Mail Service Library, Boyce, Virginia.

External links

- Great Northern Railway Post Office Car No. 42 — photographs and short history of an RPO built in 1950.

- A film clip of a train picking up a mail bag is available for viewing at the Internet Archive

- Mobile Post Office Society

- TPO and Seapost Society