Royal Hospital Haslar

| Royal Hospital Haslar | |

|---|---|

| Royal Navy Ministry of Defence Portsmouth Hospitals NHS Trust | |

Royal Hospital Haslar | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Gosport, Hampshire, England, United Kingdom |

| Coordinates | 50°47′10″N 1°07′26″W / 50.786°N 1.124°W |

| Organisation | |

| Care system | Naval / Military / NHS |

| Services | |

| Beds | Up to 350 |

| History | |

| Opened | 1753 |

| Closed | 2009 |

| Links | |

| Lists | Hospitals in England |

The Royal Hospital Haslar in Gosport, Hampshire, which was also known as the Royal Naval Hospital Haslar, was one of Britain's leading Royal Naval Hospitals (and latterly a tri-service MOD hospital) for over 250 years. Built in the 1740s, it was reputedly the largest hospital in the world when it opened,[1] and the largest brick-built building in Europe.[2]

In 1998 the closure of the hospital was announced, conditional on the establishment of an MOD Hospital Unit at a nearby civilian hospital. In 2007 the military withdrew; Haslar then continued to function for a short time under civilian management, before closing entirely in 2009. In 2018, the historic buildings began to be converted into retirement flats, and in 2020 the site reopened as Royal Haslar: a 'luxury waterfront residential village'.[3]

A significant number of Georgian, Victorian and Edwardian former hospital buildings are being preserved on the site; they are currently (2024) in the process of being converted to a variety of residential, business, retail and leisure uses.[4] The 18th-century quadrangle blocks are Grade II* listed,[5] as is the hospital chapel;[6] while around a dozen other buildings and structures on the site are listed at Grade II.[7] Most of the post-war hospital buildings have now been demolished.[8]

History

Background

At the start of the 18th century there was little provision for the medical care of naval personnel beyond the presence of surgeons on naval ships. If necessary, on-shore premises could be hired to serve as temporary 'sick quarters', beds might be reserved for naval use in the main London hospitals and civilian surgeons engaged under contract.[1]

The Fifth Commission for Sick, Wounded and Prisoners had lobbied for the establishment of dedicated naval hospitals as early as 1702, but although a number were established overseas no moves were made to build one in Britain. In a twelve-month period in 1739-40, however, nearly 17,000 sick and wounded seamen came ashore in Portsmouth and Plymouth as a result of the War of Jenkins' Ear, and the old systems of treatment and care were unable to cope. In 1741 the Commissioners for Sick and Hurt Seamen again petitioned the Admiralty to build hospitals to meet the pressing need. Eventually the Admiralty concurred that they would indeed be a good investment; and in 1744 an Order in Council was issued for the establishment of Naval Hospitals close to Portsmouth, Plymouth and Chatham.[1]

Construction

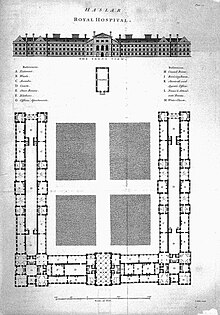

The Admiralty selected and acquired the site for the Portsmouth hospital in 1745: Haslar Farm (whose name came from Anglo-Saxon Hæsel-ōra English: Hazel Bank).[9] The building was designed by Theodore Jacobsen.[10]

Foundations were laid in 1746 and the main front building was completed in 1753. The first hundred patients were admitted on 23 October that year, but the hospital was still unfinished; construction continued until 1762, when the two parallel side wings were finished.[11]

Even then the hospital remained incomplete: the planned fourth side of the quadrangle was never built. Instead a detached chapel, dedicated to St Luke, was constructed at what would have been its centre-point;[12] (within its pediment an original hour-striking clock by Colley of London, dated 1762, continues to do service).[2]

Each wing consisted of a double row of buildings, with wards on three storeys and within the attic spaces (except that the ground floor of the inner buildings formed an arcaded walkway, opening on to the centre ground).[5] The tall centrepiece of the main front, which was aligned with the main entrance, was topped with a sculpted pediment in Portland stone, while an archway below led to the courtyard beyond.[5] The side wings were of a plainer design, with low pavilions at the centre on each side (which were used as store rooms in the early years).[5] The corner blocks initially contained apartments for the officers of the hospital.[13]

Around the hospital were some 33 acres (13 ha) of 'airing grounds' (where patients could walk and take the air); the site as a whole, of around 46 acres (19 ha), was enclosed within high brick walls. Building works cost more than £100,000, nearly double the cost of the Admiralty headquarters in London.[14] In its early years it was known as the Royal Hospital Haslar.[9]

Operation

18th century

Patients usually arrived by boat, at a jetty directly opposite the main gate (it was not until 1795 that a bridge was built over Haslar Creek, providing a direct link to Gosport;[9] up to this date the hospital employed a ferryman).[13] Built on a peninsula, the hospital's guard towers, high brick walls, and bars and railings throughout the site were all designed to stop patients, many of whom had been press ganged, from going absent without leave.[15]

The hospital had been designed to accommodate 1,500 patients, but as early as 1755 it was reconfigured to make room for up to 1,800. By 1790 overcrowding had become a serious problem, there now being 2,100 patients in the main building, and others accommodated on board hulks in Portsmouth Harbour.[12]

In the mid-18th century the hospital was administered by a 'Physician and Council': the Physician was the hospital's Senior Medical Officer; the Council consisted of two master Surgeons, the Steward and the Agent (who was responsible to the Sick and Hurt Board for assessment of new arrivals, among other duties). Accommodation was provided for the senior medical staff in two pairs of semi-detached houses, standing to either side of the main front.[16][17]

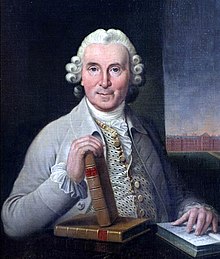

Dr James Lind (1716–1794), the 'Father of Naval Medicine',[11] served as leading physician at Haslar from 1758 till 1785. In that time he played a major part in discovering a cure for scurvy, not least through his pioneering use of a double blind methodology with Vitamin C supplements (limes).[9]

In 1794, in order to improve discipline within the hospital, its management was taken out of the hands of the clinicians and vested in serving naval officers. They were housed in a grand terrace of nine new residences, built at the south-west end of the site (beyond the chapel), facing the main quadrangle,[18] the Governor (the officer in charge) being housed in the large residence in the centre of the terrace.[19] At the same time 12 ft (3.7 m) high railings were installed across the fourth (open) side of the quadrangle to prevent desertions, and the ground floor windows of the wards were barred.[7]

Robert Dods, who was Surgeon at Haslar in the 1790s, set up a separate operating room in the Royal Hospital Haslar (which was the first in any naval hospital). Prior to this innovation, surgery had been performed on the wards in front of the other patients.[20]

The hospital treated foreign nationals as well as British service personnel. There are records of Portuguese sailors suffering from typhus being treated in the hospital in the 1790s, as well as French prisoners of war (who were being held on prison hulks nearby).[11]

By the end of the century the senior staff at Haslar are listed as a Governor and three Lieutenants, three Physicians, three Surgeons, the Agent, the Steward, a Dispenser and a Chaplain.[11] Women were employed as nurses, and there was also a support staff of labourers, cooks and other workers.[9]

19th century

In 1805 the medical staff of the naval hospitals became somewhat more integrated into Royal Navy as a whole: they were given a uniform and relative rank, and clearer conditions of appointment.[20] Notable physicians associated with Haslar in the 19th century included Sir John Richardson, Thomas Henry Huxley and William Balfour Baikie, while Sir Edward Parry served as captain-superintendent for a time in the 1840s-50s.[12]

Although it was a naval hospital, Haslar also treated large numbers of wounded soldiers, particularly between 1803 and 1815 (during the Napoleonic Wars)[9] and during the Crimean War in the 1850s.[12] During such times Army medical personnel were drafted in to work alongside their naval counterparts.[21]

In 1818 the southernmost block of the main hospital was set aside for the treatment of officers and seamen with psychiatric disorders.[22] Haslar Naval Lunatic Asylum was at the time the only such institution for naval personnel in the UK (apart from some provision at Greenwich Hospital); previously, affected personnel had been sent to Hoxton House. An early superintending psychiatrist (from 1830-38) was the phrenologist, Dr James Scott (1785–1859), a member of the influential Edinburgh Phrenological Society.[23] Under the supervision of Dr James Anderson (who was at Haslar from 1842 until his death in 1853) Haslar Asylum became known for its pioneering humane approach in treating mental illness: he abolished chains and restraints, removed the iron bars from the windows and reformed the practices of the attendants. Under him, patients were given use of the hospital grounds; they partook of music and dancing, and were also regularly taken on boating trips in Portsmouth Harbour.[24] To give them a view of the Solent, which lay beyond the high walls of the airing ground adjacent to the Asylum, Anderson created two grass-covered mounds topped by summer houses[25] (one of which still survives). In 1863 the Naval Asylum was removed from Haslar to the Royal Naval Hospital in Great Yarmouth.[26]

In the 1820s a library was established at Haslar and a museum of specimens from around the world, both created at the instigation of Sir William Burnett, which the Admiralty continued to add to over the years. The Librarian was also required to offer a course of lectures twice a year.[20] Dr James Scott was the first 'Librarian, Lecturer and Curator of the Museum'; appointed in 1827, he continued in this role alongside his work at the Asylum. Sir John Richardson succeeded him in 1838; under his curation the museum was regarded as a scientific institution of national importance, but following his resignation in 1855 much of the collection was dispersed (with several items going to Kew Gardens and the British Museum).[27] The museum was gradually restocked, but later destroyed by bombing in the Second World War. (The Library, however, survived; it has since been amalgamated into the collections of the Institute of Naval Medicine.)[12]

In the 18th and early 19th century deceased patients were buried (usually in unmarked graves) over a wide area at the south-west end of the site (later known as the Paddock). In 1826 part of it (to the north-west of the Terrace) was enclosed behind walls and consecrated as a burial ground. Burials therein ceased in 1859 when a new naval cemetery was opened a quarter of a mile away at Clayhall.[20]

In 1840 the title of Physician was abolished in the Royal Navy. That same year, the title of the senior officer of the hospital changed (having already changed from 'Governor' to 'Resident Commissioner' in 1820): it now became 'Captain-superintendent'.[20] By the early 1850s the staff consisted of:[28]

- The Captain Superintendent

- Two Lieutenants

- Two Medical Inspectors (Richardson and Anderson)

- One Deputy Medical Inspector

- The Agent & Steward (now a combined role)

- A 'Surgeon and Medical Storekeeper'

- One Assisting and eight Assistant Surgeons

- One Chaplain

- Four Clerks

To provide fresh water for the hospital a 146 ft (45 m) well had been sunk in the 18th century (on what later became the site of an adjacent naval facility: Haslar Gunboat Yard).[20] The water was raised by horse engine until 1855, when a steam engine was installed. Four years later a second well was sunk, to a depth of 340 feet (100 m). As well as driving the pumps for the wells, the engine provided water, steam and motive power for a new hospital laundry, which was built within the hospital grounds directly opposite the engine house (and connected to it via a tunnel under Haslar Road).[29] The water pumped from the wells was stored in a water tower (which was rebuilt in the 1880s),[30] while hot water from the engine was sent to a separate tank on the roof of the laundry.[11]

In 1854 the use of female nurses in the naval hospitals ceased; for the next thirty years their place was taken by men (most of whom were pensioners, discharged from active service). A new system was however instituted across the Royal Navy in 1884, with the pensioners being replaced by Sick Berth Staff (most of whom initially were boys recruited directly from Greenwich Royal Hospital School). They followed a course of training while at Haslar, and on passing an examination were rated as Sick Berth Attendants.[20] The Sick Berth Staff were overseen by a Chief Petty Officer called the Wardmaster. Working alongside the Sick Berth Staff, and supervising them in their duties, were a new female corps of trained and experienced Nursing Sisters, recruited from civilian service.[20] (The Royal Navy's Nursing Sisters were later given the designation Queen Alexandra's Royal Naval Nursing Service, in 1902.)[31]

When Greenwich Hospital closed in 1869, several of the in-pensioners moved in to the hospital at Haslar, and were accommodated in their own dedicated wards. Out-pensioners could also apply for entry. A handful of ex-Greenwich pensioners were still living there in the early 20th century.[20]

In 1870 the placing of naval officers in charge of hospitals was discontinued. In place of the Captain-superintendent and Lieutenants, the senior medical officer of the hospital (who was now called the Inspector General) regained administrative oversight.[32]

From 1881, newly-admitted naval surgeons began to be sent routinely to Haslar for a course of initial instruction (previously they had been sent to the Army's hospital at Netley).[20] A laboratory was set up for their use in the ground floor of one of the ward blocks,[11] which was used until 1899 when a purpose-built laboratory block was constructed (this is the only building on the site which is not on the same axis as the main hospital blocks; its south-facing windows were designed to provide the best light for microscopy work).[8] By this time the new recruits were receiving instruction over a four-month course in 'hygiene, the diseases of foreign stations, bacteriology and naval surgery'.[11]

20th century

In 1901 two new blocks were opened which provided staff accommodation (freeing up space within the main building): the Surgeons' Quarters (also called the Medical Officers' Mess) provided bedrooms, a dining room and social facilities for the junior medical officers; while the nearby Nursing Sisters' Mess (which was later renamed Eliza MacKenzie House) provided similarly for the staff of Queen Alexandra's Royal Naval Nursing Service up until 1996.[8] A separate hall for the labourers was opened a few years later, containing a dormitory and kitchen facilities;[20] and in 1917 the Canada Block was opened, which provided mess facilities for the Sick Berth Staff.[8]

Between 1899 and 1902 a new zymotic hospital was built in the south corner of the site, where patients with infectious diseases could be isolated. Consisting of four ward blocks connected by a covered way, with a separate administration block in the middle, it was enclosed within its own boundary wall.[20]

A separate block was opened in May 1904 for the treatment of sick officers; previously they had been treated in their own designated rooms within the main hospital building. (It was later put to other uses, and latterly functioned as the hospital's administration block.)[8]

In 1905 a set of dynamos was installed in the engine house; as well as generating electricity for the pumps and the laundry, they provided power for electric lighting, which was installed throughout the hospital (replacing the gas lamps previously employed).[11]

A new psychiatric unit was built in 1908-10, consisting of two twelve-bed wards and a padded cell; it served as an assessment unit from which patients, following diagnosis, would be sent to RNH Great Yarmouth.[33]

The hospital was kept busy during the First World War.[12] In 1918 officers of the Royal Navy Medical Service were given naval rank; until the 1970s the Medical Officer in Charge of the hospital was a Surgeon Rear-Admiral. Between the wars Haslar continued to provide preliminary training to new surgeon lieutenants, and instruction to new Sick Berth Staff.[34]

During the Second World War the hospital established the country's first blood bank, treated casualties from the Normandy landings and deployed clinicians to field hospitals in Europe and in the Far East.[9] It was also a key medical supplies centre for the fleet and for the various shore stations and auxiliary hospitals of Portsmouth Command.[34] During 1940 and 1941 there were frequent air raids: on one occasion 80% of the medical stores were destroyed by incendiary bombs; on another the library and museum (which was housed in one of the side pavilions) was completely destroyed.[35]

In 1954 Royal Hospital Haslar was renamed the Royal Naval Hospital Haslar (a designation which had already been used interchangeably at times in the 19th century) to reflect its naval traditions.[9]

A series of new extensions were begun in 1976, built over what had once been the 'airing ground' of the Asylum: the Galley, General Stores, Junior Rates Mess, Senior Rates Mess and West Wing.[36] In 1984 a new building lying between the two wings of the original hospital was opened; housing operating theatres and various patient support services, it was known as the Crosslink.[8]

In 1993, following on from the Options for Change review at the end of the Cold War, a decision was taken to cut the number of military hospitals in the UK from seven to three (one for each Service).[37] The following year, as part of Front Line First, it was announced that two more hospitals would close, leaving only Haslar (which would be reconstituted as a Joint Services institution).[37] The hospital's remit duly became tri-service in 1996 (whereupon it reverted to being called the Royal Hospital Haslar).[9] A hyperbaric medicine unit was established at the hospital at that time.[38]

Finally in December 1998, following on from the Strategic Defence Review of that year,[37] the government announced its intention to close Royal Hospital Haslar, which was by that time the UK's last remaining military hospital.[39]

21st century

In 2001 Royal Hospital Haslar began to be run by the Ministry of Defence and Portsmouth Hospitals NHS Trust in partnership; but in March 2007 the MOD withdrew its involvement.[12] To mark the handover of control to the National Health Service the military medical staff "marched out" of the hospital, exercising the unit's rights of the freedom of Gosport.[40]

Closure

All remaining medical facilities at the site were closed in 2009.[41] After services were transferred to the Ministry of Defence Hospital Unit at Queen Alexandra Hospital in Cosham, Portsmouth, the hospital closed in 2009.[9] The 25-hectare hospital site was sold to developers for £3 million later that year.[42]

On 17 May 2010 an investigation of the hospital's burial ground, by archaeologists from Cranfield Forensic Institute, was featured on Channel 4's television programme Time Team. It established that a large number of individuals (calculated as approximately 7,785[43]) had been buried in unmarked graves.[44]

Redevelopment

Plans were released in 2014 for a £152 million redevelopment scheme involving housing, commercial space, a retirement home and a hotel.[45] The hospital was converted into retirement flats to the designs of Graham Reid Architects and Heber-Percy and Parker Architects between 2018 and 2020.[46][47]

See also

- List of hospitals in England

- Royal Naval Hospital

- Royal Naval Hospital, Stonehouse (a contemporary establishment in Plymouth)

References

- ^ a b c Coad, Jonathan G. (1989). The Royal Dockyards1690-1850. Aldershot, Hants.: Scolar Press. pp. 295–297.

- ^ a b "Welcome to Haslar Heritage Group". Haslar Heritage Group. Retrieved 19 March 2024.

- ^ "History: Grand in conception, magnificent in design". Royal Haslar. Retrieved 12 March 2024.

- ^ "Site Plan". Royal Haslar. Retrieved 19 March 2024.

- ^ a b c d Historic England. "Ward blocks A, B, C, D, E, F and Centre at Royal Naval Hospital, Haslar (1233242)". National Heritage List for England.

- ^ Historic England. "Chapel of St Luke, Royal Naval Hospital, Haslar (1233560)". National Heritage List for England.

- ^ a b Historic England. "The Royal Hospital, Haslar (1001558)". National Heritage List for England.

- ^ a b c d e f "The Buildings of Haslar". Haslar Heritage Group. Retrieved 19 March 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Royal Hospital Haslar". Qaranc. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- ^ Borg, Alan (2003). "Theodore Jacobsen and the building of the Foundling Hospital" (PDF). The Georgian Group Journal. p. 12.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Sichel, Gerald (1903). Historical Notes on Haslar and the Naval Medical Profession (PDF). London: Ash & Co.

- ^ a b c d e f g Birbeck, Eric. "The Royal Hospital Haslar: from Lind to the 21st century". The James Lind Library. JLL Bulletin: Commentaries on the history of treatment evaluation. Retrieved 12 March 2024.

- ^ a b MacQueen Buchanan, Emmakate (2005). "An enlightened age: Building the naval hospitals". International Journal of Surgery. 3 (3): 221–228. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2005.03.018. PMID 17462287. Retrieved 14 April 2024.

- ^ Rodger 1986, p. 110

- ^ Brown 2016

- ^ Historic England. "Nos. 13 and 14 MOIC's Residence and attached Railings, Royal Naval Hospital, Haslar (1276719)". National Heritage List for England.

- ^ Historic England. "Nos. 11 and 12 and attached railings, Royal Naval Hospital, Haslar (1233472)". National Heritage List for England.

- ^ Historic England. "Haslar Terrace, Royal Naval Hospital, Haslar (1233482)". National Heritage List for England.

- ^ Coad, Jonathan G. (2013). Support for the Fleet: Architecture and Engineering of the Royal Navy's Bases 1700-1914. Swindon, Wilts.: English Heritage. pp. 358–362.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Tait, William (1906). A History of Haslar Hospital. Portsmouth: Griffin & Co.

- ^ Sichel, Gerald (1903). "Historical notes on Haslar and the naval medical profession" (PDF). p. 20.

- ^ Bowden-Dan, Jane (2 December 2013). "Manacles or Moral Management? Treating Insanity at Haslar Naval Lunatic Asylum". Global Maritime History. British Commission for Maritime History Seminar Series. Retrieved 20 March 2024.

- ^ The Lancet London: A Journal of British and Foreign Medicine, Surgery, Obstetrics, Physiology, Chemistry, Pharmacology, Public Health And News. Vol. 2. 1830. p. 831.

- ^ Fifteenth Report of the Commissioners in Lunacy. London: UK Parliament. 31 March 1861. pp. 11–13.

- ^ Cumming, W. F. (1852). Notes on Lunatic Asylums in Germany and other parts of Europe. London: John Churchill. p. 66.

- ^ Eighteenth Report of the Commissioners in Lunacy. London: UK Parliament. 14 June 1864. pp. 52–53.

- ^ Simpson, Daniel. "Medical Collecting on the Frontiers of Natural History: The Rise and Fall of Haslar Hospital Museum (1827-1855)" (PDF). Royal Holloway, University of London. Retrieved 22 March 2024.

- ^ Allen, Joseph (1852). The New Navy List. London: Parker, Furnivall and Parker. p. 266.

- ^ Historic England. "Laundry to the Royal Naval Hospital, Haslar (1424209)". National Heritage List for England.

- ^ Historic England. "Water Tower, Royal Naval Hospital, Haslar (1276601)". National Heritage List for England.

- ^ "Queen Alexandra's Royal Naval Nursing Service". Royal Navy. Archived from the original on 9 July 2007.

- ^ "Haslar Hospital". Hansard. 4 July 1899. Retrieved 20 March 2024.

- ^ Jones, E.; Greenberg, N. (May 2006). "Royal Naval Psychiatry: Organization, Methods and Outcomes, 1900-1945". The Mariner's Mirror. 92 (2): 190–203. doi:10.1080/00253359.2006.10656993.

- ^ a b Coulter, J. L. S. (1954). The Royal Naval Medical Service: Administration. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. pp. 310–321.

- ^ Brown, Kevin (21 December 2019). "Fittest of the fit: health and morale in the Royal Navy, 1939-1945". Journal of the Royal Naval Medical Service. 105 (3): 215. doi:10.1136/jrnms-105-215. Retrieved 25 March 2024.

- ^ "Outline Planning, Listed Building and Variation/Removal of Condition Applications for former Haslar Hospital (July 2014)" (PDF). Gosport Borough Council. Retrieved 25 March 2024.

- ^ a b c "The Strategic Defence Review: Defence Medical Services". UK Parliament. Retrieved 26 March 2024.

- ^ Glover, M (2012). "Hyperbaric Medicine Unit, Past, Present and Future". Journal of the Royal Naval Medical Service. 98 (2): 30–2. doi:10.1136/jrnms-98-30. PMID 22970644. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- ^ Henbest, Marian (30 November 2006). "Continuing fight to save Haslar". BBC News. Retrieved 20 March 2024.

- ^ "Haslar Hospital closure march". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. 29 March 2007. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- ^ "A history of Haslar hospital". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. 24 September 2014. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- ^ Fishwick, Ben (16 July 2014). "Milestone in Gosport Haslar redevelopment as plan gets green light". Portsmouth News. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- ^ Fillask (9 September 2012), Time Team Special 38 (2010) - Nelsons Hospital (Gosport, Hampshire), retrieved 9 April 2019[dead YouTube link]

- ^ "Nelson's Hospital: A Time Team Special". Radio Times. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- ^ "Regeneration Project: The Royal Haslar Gosport (GDV£152m)". Department for International Trade. 12 February 2015. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- ^ "Royal Haslar Gosport". Graham Reid Architects. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- ^ "First show homes ready to view at historic Royal Haslar". Get Surrey. 28 August 2020. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

Bibliography

- Brown, Paul (2016). Maritime Portsmouth. Stroud, Gloucestershire: The History Press. ISBN 9780750965132.

- Rodger, N. A. M. (1986). The Wooden World: An Anatomy of the Georgian Navy. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0870219871.