Punic Wars

| Punic Wars | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Territory controlled by Rome and Carthage at different times during the Punic Wars Carthaginian possessions Roman possessions | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Rome | Carthage | ||||||||

The Punic Wars were a series of wars between 264 and 146 BC fought between the Roman Republic and Ancient Carthage. Three wars took place, on both land and sea, across the western Mediterranean region and involved a total of forty-three years of warfare. The Punic Wars are also considered to include the four-year-long revolt against Carthage which started in 241 BC. Each war involved immense materiel and human losses on both sides.

The First Punic War broke out on the Mediterranean island of Sicily in 264 BC as Rome's expansion began to encroach on Carthage's sphere of influence on the island. At the start of the war Carthage was the dominant power of the western Mediterranean, with an extensive maritime empire, while Rome was a rapidly expanding power in Italy, with a strong army but no navy. The fighting took place primarily on Sicily and its surrounding waters, as well as in North Africa, Corsica, and Sardinia. It lasted 23 years, until 241 BC, when the Carthaginians were defeated. By the terms of the Treaty of Lutatius (241, amended 237 BC), Carthage paid large reparations and Sicily was annexed as a Roman province. The end of the war sparked a major but eventually unsuccessful revolt within Carthaginian territory known as the Mercenary War.

The Second Punic War began in 218 BC and witnessed the Carthaginian general Hannibal's crossing of the Alps and invasion of mainland Italy. This expedition enjoyed considerable early success and campaigned in Italy for 14 years before the survivors withdrew. There was also extensive fighting in Iberia (modern Spain and Portugal), Sicily, Sardinia, and North Africa. The successful Roman invasion of the Carthaginian homeland in Africa in 204 BC led to Hannibal's recall. He was defeated in the battle of Zama in 202 BC and Carthage sued for peace. A treaty was agreed in 201 BC which stripped Carthage of its overseas territories and some of its African ones, imposed a large indemnity, severely restricted the size of its armed forces, and prohibited Carthage from waging war without Rome's express permission. This caused Carthage to cease to be a military threat.

In 151 BC, Carthage attempted to defend itself against Numidian encroachments and Rome used this as a justification to declare war in 149 BC, starting the Third Punic War. This conflict was fought entirely on Carthage's territories in what is now Tunisia and centred on the siege of Carthage. In 146 BC, the Romans stormed the city of Carthage, sacked it, slaughtered or enslaved most of its population, and completely demolished the city. The Carthaginian territories were taken over as the Roman province of Africa. The ruins of the city lie east of modern Tunis on the North African coast.

Primary sources

The most reliable source for the Punic Wars[note 1] is the historian Polybius (c. 200 – c. 118 BC), a Greek sent to Rome in 167 BC as a hostage.[2] He is best known for The Histories, written sometime after 146 BC.[2][3] Polybius's work is considered broadly objective and largely neutral between Carthaginian and Roman points of view.[4][5] Polybius was an analytical historian and wherever possible interviewed participants from both sides in the events he wrote about.[2][6][7] Modern historians consider Polybius to have treated the relatives of Scipio Aemilianus, his patron and friend, unduly favourably, but the consensus is to accept his account largely at face value.[2][8] The modern historian Andrew Curry sees Polybius as being "fairly reliable";[9] Craige Champion describes him as "a remarkably well-informed, industrious, and insightful historian".[10] The details of the war in modern sources are largely based on interpretations of Polybius's account.[2][8][11]

The account of the Roman historian Livy is commonly used by modern historians where Polybius's account is not extant. Livy relied heavily on Polybius, but wrote in a more structured way, with more details about Roman politics, as well as being openly pro-Roman.[12][13][14] His accounts of military encounters are often demonstrably inaccurate; the classicist Adrian Goldsworthy says Livy's "reliability is often suspect",[15] and the historian Philip Sabin refers to Livy's "military ignorance".[16]

Later ancient histories of the wars also exist in fragmentary or summary form.[17] Modern historians usually take into account the writings of various Roman annalists, some contemporary; the Sicilian Greek Diodorus Siculus; and the later Roman historians[14] Plutarch, Appian,[note 2] and Dio Cassius.[19] Goldsworthy writes "Polybius' account is usually to be preferred when it differs with any of our other accounts".[note 3][2] Other sources include coins, inscriptions, archaeological evidence and empirical evidence from reconstructions, such as the trireme Olympias.[20]

Background and origin

The Roman Republic had been aggressively expanding in the southern Italian mainland for a century before the First Punic War.[21] It had conquered peninsular Italy south of the Arno River by 270 BC, when the Greek cities of southern Italy (Magna Graecia) submitted after the conclusion of the Pyrrhic War.[22] During this period of Roman expansion Carthage, with its capital in what is now Tunisia, had come to dominate southern Iberia, much of the coastal regions of North Africa, the Balearic Islands, Corsica, Sardinia and the western half of Sicily in a thalassocracy.[23]

Beginning in 480 BC Carthage fought a series of inconclusive wars against the Greek city-states of Sicily, led by Syracuse.[24] By 264 BC Carthage was the dominant external power on the island, and Carthage and Rome were the preeminent powers in the western Mediterranean.[25] Relationships were good, and the two states had several times declared their mutual friendship in formal alliances: in 509 BC, 348 BC and around 279 BC. There were strong commercial links. During the Pyrrhic War of 280–275 BC, against a king of Epirus who alternately fought Rome in Italy and Carthage on Sicily, Carthage provided materiel to the Romans and on at least one occasion provided its navy to ferry a Roman force.[26][27] According to the classicist Richard Miles, Rome had an expansionary attitude after its conquest of southern Italy, while Carthage had a proprietary approach to Sicily. The conflict between these policies pushed the two powers to stumble into war more by accident than design.[28] The spark that ignited the First Punic War in 264 BC was the issue of control of the independent Sicilian city state of Messana (modern Messina).[29][30]

Opposing forces

Armies

Most male Roman citizens were liable for military service and would serve as infantry, with a better-off minority providing a cavalry component. Traditionally, when at war the Romans would raise two legions, each of 4,200 infantry[note 4] and 300 cavalry. Approximately 1,200 members of the infantry – poorer or younger men unable to afford the armour and equipment of a standard legionary – served as javelin-armed skirmishers known as velites; they each carried several javelins, which would be thrown from a distance, as well as a short sword and a 90-centimetre (3 ft) shield.[33] The rest of the soldiers were equipped as heavy infantry, with body armour, a large shield and short thrusting swords. They were divided into three ranks: the front rank also carried two javelins, while the second and third ranks had a thrusting spear instead. Both legionary sub-units and individual legionaries fought in relatively open order. It was the long-standing Roman procedure to elect two men each year as senior magistrates, known as consuls, who in a time of war would each lead an army. An army was usually formed by combining a Roman legion with a similarly sized and equipped legion provided by their Latin allies; allied legions usually had a larger attached complement of cavalry than Roman ones.[34][35]

Carthaginian citizens only served in their army if there was a direct threat to the city of Carthage.[36][37] When they did they fought as well-armoured heavy infantry armed with long thrusting spears, although they were notoriously ill-trained and ill-disciplined. In most circumstances Carthage recruited foreigners to make up its army.[note 5] Many were from North Africa and these were frequently referred to as "Libyans". The region provided several types of fighters, including: close order infantry equipped with large shields, helmets, short swords and long thrusting spears; javelin-armed light infantry skirmishers; close order shock cavalry[note 6] (also known as "heavy cavalry") carrying spears; and light cavalry skirmishers who threw javelins from a distance and avoided close combat; the latter were usually Numidians.[40][41] The close order African infantry and the citizen-militia both fought in a tightly-packed formation known as a phalanx.[42] On occasion some of the infantry would wear captured Roman armour, especially among the troops of the Carthaginian general Hannibal.[43] In addition both Iberia and Gaul provided many experienced infantry and cavalry. The infantry from these areas were unarmoured troops who would charge ferociously, but had a reputation for breaking off if a combat was protracted.[40][44] The Gallic cavalry, and possibly some of the Iberians, wore armour and fought as close order troops; most or all of the mounted Iberians were light cavalry.[45] Slingers were frequently recruited from the Balearic Islands.[46][47] The Carthaginians also employed war elephants; North Africa had indigenous African forest elephants at the time.[note 7][44][49]

Garrison duty and land blockades were the most common operations.[50][51] When armies were campaigning, surprise attacks, ambushes and stratagems were common.[42][52] More formal battles were usually preceded by the two armies camping two–twelve kilometres (1–7 miles) apart for days or weeks; sometimes both forming up in battle order each day. If either commander felt at a disadvantage, they might march off without engaging. In such circumstances it was difficult to force a battle if the other commander was unwilling to fight.[53][54] Forming up in battle order was a complicated and premeditated affair, which took several hours. Infantry were usually positioned in the centre of the battle line, with light infantry skirmishers to their front and cavalry on each flank.[55] Many battles were decided when one side's infantry force was attacked in the flank or rear and they were partially or wholly enveloped.[42][56]

Navies

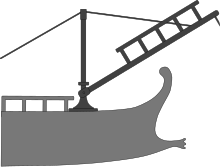

Quinqueremes, meaning "five-oarsmen",[57] provided the workhorses of the Roman and Carthaginian fleets throughout the Punic Wars.[58] So ubiquitous was the type that Polybius uses it as a shorthand for "warship" in general.[59] A quinquereme carried a crew of 300: 280 oarsmen and 20 deck crew and officers.[60] It would also normally carry a complement of 40 marines;[61] if battle was thought to be imminent this would be increased to as many as 120.[62][63]

In 260 BC Romans set out to construct a fleet and used a shipwrecked Carthaginian quinquereme as a blueprint for their own.[64] As novice shipwrights, the Romans built copies that were heavier than the Carthaginian vessels; thus they were slower and less manoeuvrable.[65] Getting the oarsmen to row as a unit, let alone to execute more complex battle manoeuvres, required long and arduous training.[66] At least half of the oarsmen would need to have had some experience if the ship was to be handled effectively.[67] As a result, the Romans were initially at a disadvantage against the more experienced Carthaginians. To counter this, the Romans introduced the corvus, a bridge 1.2 metres (4 feet) wide and 11 metres (36 feet) long, with a heavy spike on the underside, which was designed to pierce and anchor into an enemy ship's deck.[62] This allowed Roman legionaries acting as marines to board enemy ships and capture them, rather than employing the previously traditional tactic of ramming.[68]

All warships were equipped with rams, a triple set of 60-centimetre-wide (2 ft) bronze blades weighing up to 270 kilograms (600 lb) positioned at the waterline. In the century prior to the Punic Wars, boarding had become increasingly common and ramming had declined, as the larger and heavier vessels adopted in this period increasingly lacked the speed and manoeuvrability necessary to ram effectively, while their sturdier construction reduced a ram's effect on them even in case of a successful attack. The Roman adaptation of the corvus was a continuation of this trend and compensated for their initial disadvantage in ship-manoeuvring skills. The added weight in the prow compromised both the ship's manoeuvrability and its seaworthiness, and in rough sea conditions the corvus became useless; part way through the First Punic War the Romans ceased using it.[68][69][70]

First Punic War, 264–241 BC

Course

Much of the First Punic War was fought on, or in the waters near, Sicily.[71] Away from the coasts its hilly and rugged terrain made manoeuvring large forces difficult and so encouraged defensive strategies. Land operations were largely confined to raids, sieges and interdiction; in 23 years of war on Sicily there were only two full-scale pitched battles.[72]

Sicily, 264–257 BC

The war began with the Romans gaining a foothold on Sicily at Messana (modern Messina) in 264 BC.[73] They then pressed Syracuse, the only significant independent power on the island, into allying with them[74] and laid siege to Carthage's main base at Akragas on the south coast.[75] A Carthaginian army of 50,000 infantry, 6,000 cavalry and 60 elephants attempted to lift the siege in 262 BC, but was badly defeated at the battle of Akragas. That night the Carthaginian garrison escaped and the Romans seized the city and its inhabitants, selling 25,000 of them into slavery.[76]

After this the land war on Sicily reached a stalemate as the Carthaginians focused on defending their well-fortified towns and cities; these were mostly on the coast and so could be supplied and reinforced without the Romans being able to use their superior army to interfere.[77][78] The focus of the war shifted to the sea, where the Romans had little experience; on the few occasions they had previously felt the need for a naval presence they had usually relied on small squadrons provided by their Latin or Greek allies.[75][79][80] The Romans built a navy to challenge Carthage's,[81] and using the corvus inflicted a major defeat at the battle of Mylae in 260 BC.[82][83][84] A Carthaginian base on Corsica was seized, but an attack on Sardinia was repulsed; the base on Corsica was then lost.[85] In 258 BC a Roman fleet defeated a smaller Carthaginian fleet at the battle of Sulci off the western coast of Sardinia.[83]

Africa, 256–255 BC

Taking advantage of their naval victories the Romans launched an invasion of North Africa in 256 BC,[86] which the Carthaginians intercepted at the battle of Cape Ecnomus off the southern coast of Sicily. The Carthaginian's superior seamanship was not as effective as they had hoped, while the Romans' corvus gave them an edge as the battle degenerated into a shapeless brawl.[63][87] The Carthaginians were again beaten;[88] this was possibly the largest naval battle in history by the number of combatants involved.[note 8][89][90][91] The invasion initially went well and in 255 BC the Carthaginians sued for peace; the proposed terms were so harsh they decided to fight on.[92] At the battle of Tunis in spring 255 BC a combined force of infantry, cavalry and war elephants under the command of the Spartan mercenary Xanthippus crushed the Romans.[93] The Romans sent a fleet to evacuate their survivors and the Carthaginians opposed it at the battle of Cape Hermaeum (modern Cape Bon); the Carthaginians were again heavily defeated.[94] The Roman fleet, in turn, was devastated by a storm while returning to Italy, losing most of its ships and more than 100,000 men.[95][96][97] It is possible that the presence of the corvus, making the Roman ships unusually unseaworthy, contributed to this disaster; there is no record of them being used again.[98][99]

Sicily, 255–241 BC

The war continued, with neither side able to gain a decisive advantage.[100] The Carthaginians attacked and recaptured Akragas in 255 BC, but not believing they could hold the city they razed and abandoned it.[101][102] The Romans rapidly rebuilt their fleet, adding 220 new ships, and captured Panormus (modern Palermo) in 254 BC.[103] The next year they lost another 150 ships to a storm.[104] On Sicily the Romans avoided battle in 252 and 251 BC, according to Polybius because they feared the war elephants which the Carthaginians had shipped to the island.[105][106] In 250 BC the Carthaginians advanced on Panormus, but in a battle outside the walls the Romans drove off the Carthaginian elephants with javelins. The elephants routed through the Carthaginian infantry, who were then charged by the Roman infantry to complete their defeat.[106][107]

Slowly the Romans had occupied most of Sicily; in 250 BC they besieged the last two Carthaginian strongholds – Lilybaeum and Drepana in the extreme west.[108] Repeated attempts to storm Lilybaeum's strong walls failed, as did attempts to block access to its harbour, and the Romans settled down to a siege which was to last nine years.[109][110] They launched a surprise attack on the Carthaginian fleet, but were defeated at the battle of Drepana; Carthage's greatest naval victory of the war.[111] Carthage turned to the maritime offensive, inflicting another heavy naval defeat at the battle of Phintias and all but swept the Romans from the sea.[112] It was to be seven years before Rome again attempted to field a substantial fleet, while Carthage put most of its ships into reserve to save money and free up manpower.[113][114]

Roman victory, 243–241 BC

After more than 20 years of war, both states were financially and demographically exhausted.[115] Evidence of Carthage's financial situation includes their request for a 2,000-talent loan[note 9] from Ptolemaic Egypt, which was refused.[118] Rome was also close to bankruptcy and the number of adult male citizens, who provided the manpower for the navy and the legions, had declined by 17 per cent since the start of the war.[119] Historian Adrian Goldsworthy (2006) has described Roman manpower losses as "appalling".[120]

The Romans rebuilt their fleet again in 243 BC after the Senate approached Rome's wealthiest citizens for loans to finance the construction of one ship each, repayable from the reparations to be imposed on Carthage once the war was won.[121] This new fleet effectively blockaded the Carthaginian garrisons.[117] Carthage assembled a fleet which attempted to relieve them, but it was destroyed at the battle of the Aegates Islands in 241 BC,[122][123] forcing the cut-off Carthaginian troops on Sicily to negotiate for peace.[117][124]

The Treaty of Lutatius was agreed by which Carthage paid 3,200 talents of silver[note 10] in reparations and Sicily was annexed as a Roman province.[122] Polybius regarded the war as "the longest, most continuous and most severely contested war known to us in history".[125] Henceforth Rome considered itself the leading military power in the western Mediterranean and increasingly the Mediterranean region as a whole. The immense effort of repeatedly building large fleets of galleys during the war laid the foundation for Rome's maritime dominance, which was to last 600 years.[126]

Interbellum, 241–218 BC

Mercenary War

The Mercenary, or Truceless, War began in 241 BC as a dispute over the payment of wages owed to 20,000 foreign soldiers who had fought for Carthage on Sicily during the First Punic War. This erupted into full-scale mutiny under the leadership of Spendius and Matho; 70,000 Africans from Carthage's oppressed dependant territories flocked to join the mutineers, bringing supplies and finance.[127][128] War-weary Carthage fared poorly in the initial engagements, especially under the generalship of Hanno.[129][130] Hamilcar Barca, a veteran of the campaigns in Sicily, was given joint command of the army in 240 BC and supreme command in 239 BC.[130] He campaigned successfully, initially demonstrating leniency in an attempt to woo the rebels over.[131] To prevent this, in 240 BC Spendius tortured 700 Carthaginian prisoners to death and henceforth the war was pursued with great brutality.[132][133]

By early 237 BC, after numerous setbacks, the rebels were defeated and their cities brought back under Carthaginian rule.[134] An expedition was prepared to reoccupy Sardinia, where mutinous soldiers had slaughtered all Carthaginians. The Roman Senate stated they considered the preparation of this force an act of war and demanded Carthage cede Sardinia and Corsica and pay an additional 1,200-talent indemnity.[note 11][135][136] Weakened by 30 years of war, Carthage agreed rather than again enter into conflict with Rome.[137] Polybius considered this "contrary to all justice" and modern historians have variously described the Romans' behaviour as "unprovoked aggression and treaty-breaking",[135] "shamelessly opportunistic"[138] and an "unscrupulous act".[139] These events fuelled resentment of Rome in Carthage, which was not reconciled to Rome's perception of its situation. This breach of the recently signed treaty is considered by modern historians to be the single greatest cause of war with Carthage breaking out again in 218 BC in the Second Punic War.[140][141][142]

Carthaginian expansion in Iberia

With the suppression of the rebellion, Hamilcar understood that Carthage needed to strengthen its economic and military base if it were to again confront Rome.[144] After the First Punic War, Carthaginian possessions in Iberia (modern Spain and Portugal) were limited to a handful of prosperous coastal cities in the south.[145] Hamilcar took the army which he had led in the Mercenary War to Iberia in 237 BC and carved out a quasi-monarchial, autonomous state in its south east.[146] This gave Carthage the silver mines, agricultural wealth, manpower, military facilities such as shipyards, and territorial depth to stand up to future Roman demands with confidence.[147][148] Hamilcar ruled as a viceroy and was succeeded by his son-in-law, Hasdrubal, in the early 220s BC and then his son, Hannibal, in 221 BC.[149] In 226 BC the Ebro Treaty was agreed with Rome, specifying the Ebro River as the northern boundary of the Carthaginian sphere of influence.[150] At some time during the next six years Rome made a separate agreement with the city of Saguntum, which was situated well south of the Ebro.[151]

Second Punic War, 218–201 BC

In 219 BC a Carthaginian army under Hannibal besieged, captured and sacked Saguntum[note 12][140][152] and in spring 218 BC Rome declared war on Carthage.[153] There were three main military theatres in the war: Italy, where Hannibal defeated the Roman legions repeatedly, with occasional subsidiary campaigns in Sicily, Sardinia and Greece; Iberia, where Hasdrubal, a younger brother of Hannibal, defended the Carthaginian colonial cities with mixed success until moving into Italy; and Africa, where the war was decided.[154]

Italy

Hannibal crosses the Alps, 218–217 BC

In 218 BC there was some naval skirmishing in the waters around Sicily; the Romans defeated a Carthaginian attack[155][156] and captured the island of Malta.[157] In Cisalpine Gaul (modern northern Italy), the major Gallic tribes attacked the Roman colonies there, causing the Roman settlers to flee to their previously-established colony of Mutina (modern Modena), where they were besieged. A Roman relief force broke through the siege, but was then ambushed and besieged itself.[158] An army had previously been created by the Romans to campaign in Iberia and the Roman Senate detached one Roman and one allied legion from it to send to north Italy. Raising fresh troops to replace these delayed the army's departure for Iberia until September.[159]

Meanwhile, Hannibal assembled a Carthaginian army in New Carthage (modern Cartagena) in Iberia and led it northwards along the coast in May or June. It entered Gaul and took an inland route, to avoid the Roman allies to the south.[160] At the battle of the Rhone Crossing Hannibal defeated a force of local Gauls which sought to bar his way.[161] A Roman fleet carrying the Iberian-bound army landed at Rome's ally Massalia (modern Marseille) at the mouth of the Rhone,[162] but Hannibal evaded the Romans and they continued to Iberia.[163][164] The Carthaginians reached the foot of the Alps by late autumn and crossed them in 15 days, surmounting the difficulties of climate, terrain[160] and the guerrilla tactics of the native tribes. Hannibal arrived with 20,000 infantry, 6,000 cavalry and an unknown number of elephants – the survivors of the 37 with which he left Iberia[74][165] – in what is now Piedmont, northern Italy in early November; the Romans were still in their winter quarters. His surprise entry into the Italian peninsula led to the cancellation of Rome's planned campaign for the year: an invasion of Africa.[166]

Roman defeats, 217–216 BC

The Carthaginians captured the chief city of the hostile Taurini (in the area of modern Turin) and seized its food stocks.[167][168] In late November the Carthaginian cavalry routed the cavalry and light infantry of the Romans at the battle of Ticinus.[169] As a result, most of the Gallic tribes declared for the Carthaginian cause and Hannibal's army grew to 37,000 men.[170] A large Roman army was lured into combat by Hannibal at the battle of the Trebia, encircled and destroyed.[171][172] Only 10,000 Romans out of 42,000 were able to cut their way to safety. Gauls now joined Hannibal's army in large numbers.[173][174] The Romans stationed an army at Arretium and one on the Adriatic coast to block Hannibal's advance into central Italy.[175][176]

In early spring 217 BC, the Carthaginians crossed the Apennines unopposed, taking a difficult but unguarded route.[177] Hannibal attempted to draw the main Roman army under Gaius Flaminius into a pitched battle by devastating the area they had been sent to protect,[178] provoking Flaminius into a hasty pursuit without proper reconnaissance. Hannibal set an ambush and in the battle of Lake Trasimene completely defeated the Roman army, killing 15,000 Romans, including Flaminius, and taking 15,000 prisoners. A cavalry force of 4,000 from the other Roman army was also engaged and wiped out.[179][180] The prisoners were badly treated if they were Romans, but released if they were from one of Rome's Latin allies.[174] Hannibal hoped some of these allies could be persuaded to defect and marched south hoping to win over Roman allies among the ethnic Greek and Italic states.[175][181]

The Romans, panicked by these heavy defeats, appointed Quintus Fabius as dictator, with sole charge of the war effort.[182] Fabius introduced the Fabian strategy of avoiding open battle with his opponent, but constantly skirmishing with small detachments of the enemy. This was not popular with parts of the Roman army, public and senate, since he avoided battle while Italy was being devastated by the enemy.[175][183] Hannibal marched through the richest and most fertile provinces of Italy, hoping the devastation would draw Fabius into battle, but Fabius refused.[184]

In the 216 BC elections Gaius Varro and Lucius Paullus were elected as consuls; both were more aggressive-minded than Fabius.[185][186] The Roman Senate authorised the raising of a force of 86,000 men, the largest in Roman history to that point.[187][188] Paullus and Varro marched southward to confront Hannibal, who accepted battle on the open plain near Cannae. In the battle of Cannae the Roman legions forced their way through Hannibal's deliberately weak centre, but Libyan heavy infantry on the wings swung around their advance, menacing their flanks. Hasdrubal[note 13] led the Carthaginian cavalry on the left wing and routed the Roman cavalry opposite, then swept around the rear of the Romans to attack the cavalry on the other wing. He then charged into the legions from behind. As a result, the Roman infantry was surrounded with no means of escape.[190] At least 67,500 Romans were killed or captured.[191]

The historian Richard Miles describes Cannae as "Rome's greatest military disaster".[192] Toni Ñaco del Hoyo describes the Trebia, Lake Trasimene and Cannae as the three "great military calamities" suffered by the Romans in the first three years of the war.[193] Brian Carey writes that these three defeats brought Rome to the brink of collapse.[194] Within a few weeks of Cannae a Roman army of 25,000 was ambushed by Boii Gauls at the battle of Silva Litana and annihilated.[195] Fabius was elected consul in 215 BC and was re-elected in 214 BC.[196][197]

Roman allies defect, 216–207 BC

Little survives of Polybius's account of Hannibal's army in Italy after Cannae and Livy is the best surviving source for this part of the war.[12][15][16] Several of the city states in southern Italy allied with Hannibal or were captured when pro-Carthaginian factions betrayed their defences. These included the large city of Capua and the major port city of Tarentum (modern Taranto). Two of the major Samnite tribes also joined the Carthaginian cause. By 214 BC the bulk of southern Italy had turned against Rome, although there were many exceptions. The majority of Rome's allies in central Italy remained loyal. All except the smallest towns were too well fortified for Hannibal to take by assault and blockade could be a long-drawn-out affair, or, if the target was a port, impossible. Carthage's new allies felt little sense of community with Carthage, or even with each other. The new allies increased the number of places that Hannibal's army was expected to defend from Roman retribution, but provided relatively few fresh troops to assist him in doing so. Such Italian forces as were raised resisted operating away from their home cities and performed poorly when they did.[198][199]

When the port city of Locri defected to Carthage in the summer of 215 BC it was immediately used to reinforce the Carthaginian forces in Italy with soldiers, supplies and war elephants.[200] It was the only time during the war that Carthage reinforced Hannibal.[201] A second force, under Hannibal's youngest brother Mago, was meant to land in Italy in 215 BC but was diverted to Iberia after the Carthaginian defeat there at the battle of Dertosa.[200][202]

Meanwhile, the Romans took drastic steps to raise new legions: enrolling slaves, criminals and those who did not meet the usual property qualification.[203] By early 215 BC they were fielding at least 12 legions; by 214 BC, 18; and by 213 BC, 22. By 212 BC the full complement of the legions deployed would have been in excess of 100,000 men, plus, as always, a similar number of allied troops. The majority were deployed in southern Italy in field armies of approximately 20,000 men each. This was insufficient to challenge Hannibal's army in open battle, but sufficient to force him to concentrate his forces and to hamper his movements.[196]

For 12 years after Cannae the war surged around southern Italy as cities went over to the Carthaginians or were taken by subterfuge and the Romans recaptured them by siege or by suborning pro-Roman factions.[204] Hannibal repeatedly defeated Roman armies, in 209 BC both consuls were killed in a cavalry skirmish. But wherever his main army was not active the Romans threatened Carthaginian-supporting towns or sought battle with Carthaginian or Carthaginian-allied detachments; frequently with success.[116][205] By 207 BC Hannibal had been confined to the extreme south of Italy and many of the cities and territories which had joined the Carthaginian cause had returned to their Roman allegiance.[206]

Greece, Sardinia and Sicily

During 216 BC the Macedonian king, Philip V, pledged his support to Hannibal,[207] initiating the First Macedonian War against Rome in 215 BC. In 211 BC Rome contained this threat by allying with the Aetolian League, a coalition of Greek city states which was already at war against Macedonia. In 205 BC this war ended with a negotiated peace.[208]

A rebellion in support of the Carthaginians broke out on Sardinia in 213 BC, but it was quickly put down by the Romans.[209]

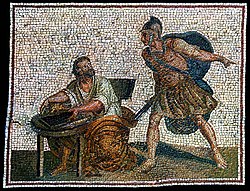

Up to 215 BC Sicily remained firmly in Roman hands, blocking the ready seaborne reinforcement and resupply of Hannibal from Carthage. Hiero II, the tyrant of Syracuse for the previous forty-five years and a staunch Roman ally, died in that year and his successor Hieronymus was discontented with his situation. Hannibal negotiated a treaty whereby Syracuse defected to Carthage, in exchange for making the whole of Sicily a Syracusan possession. The Syracusan army proved no match for a Roman army led by Claudius Marcellus and by spring 213 BC Syracuse was besieged.[210][211] The siege was marked by the ingenuity of Archimedes in inventing war machines to counteract the traditional siege warfare methods of the Romans.[212]

A large Carthaginian army led by Himilco was sent to relieve the city in 213 BC.[209][213] It captured several Roman-garrisoned towns on Sicily; many Roman garrisons were either expelled or massacred by Carthaginian partisans. In spring 212 BC the Romans stormed Syracuse in a surprise night assault and captured several districts of the city. Meanwhile, the Carthaginian army was crippled by plague. After the Carthaginians failed to resupply the city, Syracuse fell that autumn; Archimedes was killed by a Roman soldier.[213]

Carthage sent more reinforcements to Sicily in 211 BC and went on the offensive. A fresh Roman army attacked the main Carthaginian stronghold on the island, Agrigentum, in 210 BC and the city was betrayed to the Romans by a discontented Carthaginian officer. The remaining Carthaginian-controlled towns then surrendered or were taken through force or treachery[214][215] and the Sicilian grain supply to Rome and its armies was secured.[216]

Italy, 207–203 BC

In the spring of 207 BC Hasdrubal Barca repeated the feat of his elder brother by marching an army of 35,000 men across the Alps and invading Italy. His aim was to join his forces with those of Hannibal, but Hannibal was unaware of his presence. The Romans facing Hannibal in southern Italy tricked him into believing the whole Roman army was still in camp, while a large portion marched north under the consul Claudius Nero and reinforced the Romans facing Hasdrubal, who were commanded by the other consul, Marcus Salinator. The combined Roman force attacked Hasdrubal at the battle of the Metaurus and destroyed his army, killing Hasdrubal. This battle confirmed Roman dominance in Italy and marked the end of their Fabian strategy.[217][218]

In 205 BC, Mago landed in Genua in north-west Italy with the remnants of his Spanish army (see § Iberia below) where it received Gallic and Ligurian reinforcements. Mago's arrival in the north of the Italian peninsula was followed by Hannibal's inconclusive battle of Crotona in 204 BC in the far south of the peninsula. Mago marched his reinforced army towards the lands of Carthage's main Gallic allies in the Po Valley, but was checked by a large Roman army and defeated at the battle of Insubria in 203 BC.[219]

After Publius Cornelius Scipio invaded the Carthaginian homeland in 204 BC, defeating the Carthaginians in two major battles and winning the allegiance of the Numidian kingdoms of North Africa, Hannibal and the remnants of his army were recalled.[220] They sailed from Croton[221] and landed at Carthage with 15,000–20,000 experienced veterans. Mago was also recalled; he died of wounds on the voyage and some of his ships were intercepted by the Romans,[222] but 12,000 of his troops reached Carthage.[223]

Iberia

Iberia, 218–209 BC

The Roman fleet continued on from Massala in the autumn of 218 BC, landing the army it was transporting in north-east Iberia, where it won support among the local tribes.[163] A rushed Carthaginian attack in late 218 BC was beaten back at the battle of Cissa.[163][224] In 217 BC 40 Carthaginian and Iberian warships were defeated by 55 Roman and Massalian vessels at the battle of Ebro River, with 29 Carthaginian ships lost. The Romans' lodgement between the Ebro and the Pyrenees blocked the route from Iberia to Italy and greatly hindered the despatch of reinforcements from Iberia to Hannibal.[224] The Carthaginian commander in Iberia, Hannibal's brother Hasdrubal, marched into this area in 215 BC, offered battle and was defeated at Dertosa, although both sides suffered heavy casualties.[225]

The Carthaginians suffered a wave of defections of local Celtiberian tribes to Rome.[163] The Roman commanders captured Saguntum in 212 BC and in 211 BC hired 20,000 Celtiberian mercenaries to reinforce their army. Observing that the three Carthaginian armies were deployed apart from each other, the Romans split their forces.[225] This strategy resulted in two separate battles in 211 BC, usually referred to jointly as the battle of the Upper Baetis. Both battles ended in complete defeat for the Romans, as Hasdrubal had bribed the Romans' mercenaries to desert. The Romans retreated to their coastal stronghold north of the Ebro, from which the Carthaginians again failed to expel them.[163][225] Claudius Nero brought over reinforcements in 210 BC and stabilised the situation.[225]

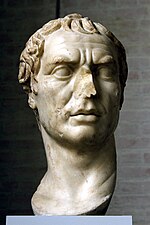

In 210 BC Publius Cornelius Scipio,[note 14] arrived in Iberia with further Roman reinforcements.[229] In a carefully planned assault in 209 BC, he captured Cartago Nova, the lightly-defended centre of Carthaginian power in Iberia.[229][230] Scipio seized a vast booty of gold, silver and siege artillery, but released the captured population. He also liberated the Iberian hostages who had been held there by the Carthaginians to ensure the loyalty of their tribes.[229][231] Even so, many of them later fought against the Romans.[229]

Roman victory in Iberia, 208–205 BC

In the spring of 208 BC Hasdrubal moved to engage Scipio at the battle of Baecula.[232] The Carthaginians were defeated, but Hasdrubal was able to withdraw the majority of his army and prevent any Roman pursuit; most of his losses were among his Iberian allies. Scipio was not able to prevent Hasdrubal from leading his depleted army through the western passes of the Pyrenees into Gaul. In 207 BC, after recruiting heavily in Gaul, Hasdrubal crossed the Alps into Italy in an attempt to join his brother, Hannibal, but was defeated before he could.[232][233][234]

In 206 BC at the Battle of Ilipa, Scipio with 48,000 men, half Italian and half Iberian, defeated a Carthaginian army of 54,500 men and 32 elephants. This sealed the fate of the Carthaginians in Iberia.[229][235] The last Carthaginian-held city in Iberia, Gades, defected to the Romans.[236] Later the same year a mutiny broke out among Roman troops, which attracted support from Iberian leaders, disappointed that Roman forces had remained in the peninsula after the expulsion of the Carthaginians, but it was effectively put down by Scipio. In 205 BC a last attempt was made by Mago to recapture New Carthage when the Roman occupiers were shaken by another mutiny and an Iberian uprising, but he was repulsed. Mago left Iberia for Cisalpine Gaul with his remaining forces.[231] In 203 BC Carthage succeeded in recruiting at least 4,000 mercenaries from Iberia, despite Rome's nominal control.[237]

Africa

In 213 BC Syphax, a powerful Numidian king in North Africa, declared for Rome. In response, Roman advisers were sent to train his soldiers and he waged war against the Carthaginian ally Gala.[225] In 206 BC the Carthaginians ended this drain on their resources by dividing several Numidian kingdoms with him. One of those disinherited was the Numidian prince Masinissa, who was thus driven into the arms of Rome.[238]

Scipio's invasion of Africa, 204–201 BC

In 205 BC Publius Scipio was given command of the legions in Sicily and allowed to enrol volunteers for his plan to end the war by an invasion of Africa.[239] After landing in Africa in 204 BC, he was joined by Masinissa and a force of Numidian cavalry.[240] Scipio gave battle to and destroyed two large Carthaginian armies.[220] After the second of these Syphax was pursued and taken prisoner by Masinissa at the battle of Cirta; Masinissa then seized most of Syphax's kingdom with Roman help.[241]

Rome and Carthage entered into peace negotiations and Carthage recalled Hannibal from Italy.[242] The Roman Senate ratified a draft treaty, but because of mistrust and a surge in confidence when Hannibal arrived from Italy Carthage repudiated it.[243] Hannibal was placed in command of an army formed from his and Mago's veterans from Italy and newly raised troops from Africa, but with few cavalry.[244] The decisive battle of Zama followed in October 202 BC.[245][246] Unlike most battles of the Second Punic War, the Romans had superiority in cavalry and the Carthaginians in infantry.[244] Hannibal attempted to use 80 elephants to break into the Roman infantry formation, but the Romans countered them effectively and they routed back through the Carthaginian ranks.[247] The Roman and allied Numidian cavalry then pressed their attacks and drove the Carthaginian cavalry from the field. The two sides' infantry fought inconclusively until the Roman cavalry returned and attacked the Carthaginian rear. The Carthaginian formation collapsed; Hannibal was one of the few to escape the field.[245]

The new peace treaty dictated by Rome stripped Carthage of all of its overseas territories and some of its African ones; an indemnity of 10,000 silver talents[note 15] was to be paid over 50 years; hostages were to be taken; Carthage was forbidden to possess war elephants and its fleet was restricted to 10 warships; it was prohibited from waging war outside Africa and in Africa only with Rome's express permission. Many senior Carthaginians wanted to reject it, but Hannibal spoke strongly in its favour and it was accepted in spring 201 BC.[249] Henceforth it was clear that Carthage was politically subordinate to Rome.[250] Scipio was awarded a triumph and received the agnomen "Africanus".[251]

Under the pressure of the war, the Romans developed an increasingly effective system of logistics to equip and feed the unprecedented numbers of soldiers they field. During the last three years of the war this was extended to the transporting by sea from Sicily to Africa of almost all of the requirements of Scipio's large army. These developments made possible the subsequent Roman overseas wars of conquest.[252]

Interbellum, 201–149 BC

At the end of the war, Masinissa emerged as by far the most powerful ruler among the Numidians.[253] Over the following 48 years he repeatedly took advantage of Carthage's inability to protect its possessions. Whenever Carthage petitioned Rome for redress, or permission to take military action, Rome backed its ally, Masinissa, and refused.[254] Masinissa's seizures of and raids into Carthaginian territory became increasingly flagrant. In 151 BC Carthage raised an army, the treaty notwithstanding, and counterattacked the Numidians. The campaign ended in disaster for the Carthaginians and their army surrendered.[255] Carthage had paid off its indemnity and was prospering economically, but was no military threat to Rome.[256][257] Elements in the Roman Senate had long wished to destroy Carthage and with the breach of the treaty as a casus belli, war was declared in 149 BC.[255]

Third Punic War, 149–146 BC

In 149 BC a Roman army of approximately 50,000 men, jointly commanded by both consuls, landed near Utica, 35 kilometres (22 mi) north of Carthage.[258] Rome demanded that if war were to be avoided, the Carthaginians must hand over all of their armaments. Vast amounts of materiel were delivered, including 200,000 sets of armour, 2,000 catapults and a large number of warships.[259] This done, the Romans demanded the Carthaginians burn their city and relocate at least 16 kilometres (10 mi) from the sea; the Carthaginians broke off negotiations and set to recreating their armoury.[260]

Siege of Carthage

As well as manning the walls of Carthage, the Carthaginians formed a field army under Hasdrubal the Boetharch, which was based 25 kilometres (16 mi) to the south.[262][263] The Roman army moved to lay siege to Carthage, but its walls were so strong and its citizen-militia so determined it was unable to make any impact, while the Carthaginians struck back effectively. Their army raided the Roman lines of communication,[263] and in 148 BC Carthaginian fire ships destroyed many Roman vessels. The main Roman camp was in a swamp, which caused an outbreak of disease during the summer.[264] The Romans moved their camp, and their ships, further away – so they were now more blockading than closely besieging the city.[265] The war dragged on into 147 BC.[263]

In early 147 BC, Scipio Aemilianus, an adopted grandson of Scipio Africanus who had distinguished himself during the previous two years' fighting, was elected consul and took control of the war.[255][266] The Carthaginians continued to resist vigorously: they constructed warships and, during the summer, twice gave battle to the Roman fleet, losing both times.[266] The Romans launched an assault on the walls; after confused fighting they broke into the city, but, lost in the dark, withdrew. Hasdrubal and his army retreated into the city to reinforce the garrison.[267] Hasdrubal had Roman prisoners tortured to death on the walls, in view of the Roman army. He was reinforcing the will to resist in the Carthaginian citizens; from this point there could be no possibility of negotiations. Some members of the city council denounced his actions and Hasdrubal had them put to death and took control of the city.[266][268] With no Carthaginian army in the field, those cities which had remained loyal went over to the Romans or were captured.[269]

Scipio moved back to a close blockade of the city and built a mole which cut off supply from the sea.[270] In the spring of 146 BC, the Roman army managed to secure a foothold on the fortifications near the harbour.[271][272] Scipio launched a major assault which quickly captured the city's main square, where the legions camped overnight.[273] The next morning, the Romans started systematically working their way through the residential part of the city, killing everyone they encountered and firing the buildings behind them.[271] At times, the Romans progressed from rooftop to rooftop, to prevent missiles being hurled down on them.[273] It took six days to clear the city of resistance; only on the last day did Scipio take prisoners. The last holdouts, including Roman deserters in Carthaginian service, fought on from the Temple of Eshmoun and burnt it down around themselves when all hope was gone.[274] There were 50,000 Carthaginian prisoners, a small proportion of the pre-war population, who were sold into slavery.[275] There is a tradition that Roman forces then sowed the city with salt, but this has been shown to have been a 19th-century invention.[276][277]

Aftermath

The remaining Carthaginian territories were annexed by Rome and reconstituted to become the Roman province of Africa with Utica as its capital.[278] The province became a major source of grain and other foodstuffs.[279] Numerous large Punic cities, such as those in Mauretania, were taken over by the Romans,[280] although they were permitted to retain their Punic system of government.[281] A century later, the site of Carthage was rebuilt as a Roman city by Julius Caesar; it became one of the main cities of Roman Africa by the time of the Empire.[282][283] Rome still exists as the capital of Italy;[284] the ruins of Carthage lie 24 kilometres (15 mi) east of Tunis on the North African coast.[285][286]

See also

Notes, citations, and sources

Notes

- ^ The term Punic comes from the Latin word Punicus (or Poenicus), meaning "Carthaginian" and is a reference to the Carthaginians' Phoenician ancestry.[1]

- ^ Whose account of the Third Punic War is especially valuable.[18]

- ^ Sources other than Polybius are discussed by Bernard Mineo in "Principal Literary Sources for the Punic Wars (apart from Polybius)".[19]

- ^ This could be increased to 5,000 in some circumstances,[31] or, rarely, even more.[32]

- ^ Roman and Greek sources refer to these foreign fighters derogatively as "mercenaries", but the modern historian Adrian Goldsworthy describes this as "a gross oversimplification". They served under a variety of arrangements; for example, some were the regular troops of allied cities or kingdoms seconded to Carthage as part of formal treaties, some were from allied states fighting under their own leaders, many were volunteers from areas under Carthaginian control who were not Carthaginian citizens. (Which was largely reserved for inhabitants of the city of Carthage.)[38]

- ^ "Shock" troops are those trained and used to close rapidly with an opponent, with the intention of breaking them before, or immediately upon, contact.[39]

- ^ These elephants were typically about 2.5 m (8 ft 2 in) high at the shoulder and should not be confused with the larger African bush elephant.[48]

- ^ Polybius gives 140,000 personnel in the Roman fleet and 150,000 in the Carthaginian; these figures are broadly accepted by historians of the conflict.[89][90][91]

- ^ Several different "talents" are known from antiquity. The ones referred to in this article are all Euboic (or Euboeic) talents, of approximately 26 kilograms (57 lb).[116][117] 2,000 talents was approximately 52,000 kilograms (51 long tons) of silver.[116]

- ^ 3,200 talents was approximately 82,000 kg (81 long tons).[116]

- ^ 1,200 talents was approximately 30,000 kg (30 long tons) of silver.[116]

- ^ There is scholarly debate as to whether Saguntum was a formal Roman ally, in which case attacking it may have been a breach of the clause in the Treaty of Lutatius prohibiting attacking each others allies; or whether the city had less formally requested Rome's protection, and possibly been granted it. In either case, the Carthaginians argued that relationships entered into after the signing of the treaty were not covered by it.[151]

- ^ Not the same man as Hasdrubal Barca, one of Hannibal's younger brothers.[189]

- ^ Publius Scipio was the bereaved son of the previous Roman co-commander in Iberia, also named Publius Scipio, and the nephew of the other co-commander, Gnaeus Scipio.[228]

- ^ 10,000 talents was approximately 269,000 kg (265 long tons) of silver.[248]

Citations

- ^ Sidwell & Jones 1998, p. 16.

- ^ a b c d e f Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Walbank 1990, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Lazenby 1996, pp. x–xi.

- ^ Hau 2016, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Shutt 1938, p. 55.

- ^ Champion 2015, pp. 98, 101.

- ^ a b Lazenby 1996, pp. x–xi, 82–84.

- ^ Curry 2012, p. 34.

- ^ Champion 2015, p. 102.

- ^ Tipps 1985, p. 432.

- ^ a b Lazenby 1998, p. 87.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 22.

- ^ a b Champion 2015, p. 95.

- ^ a b Goldsworthy 2006, p. 222.

- ^ a b Sabin 1996, p. 62.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 21–23.

- ^ Le Bohec 2015, p. 430.

- ^ a b Mineo 2015, pp. 111–127.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 23, 98.

- ^ Miles 2011, pp. 157–158.

- ^ Bagnall 1999, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 29–30.

- ^ Miles 2011, pp. 115, 132.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Miles 2011, pp. 94, 160, 163, 164–165.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Miles 2011, pp. 175–176.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 74–75.

- ^ Warmington 1993, p. 168.

- ^ Bagnall 1999, p. 23.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 287.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 48.

- ^ Bagnall 1999, pp. 22–25.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 50.

- ^ Lazenby 1998, p. 9.

- ^ Scullard 2006, p. 494.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 33.

- ^ Jones 1987, p. 1.

- ^ a b Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 32–34.

- ^ Koon 2015, pp. 79–87.

- ^ a b c Koon 2015, p. 93.

- ^ Rawlings 2015, p. 305.

- ^ a b Bagnall 1999, p. 9.

- ^ Carey 2007, p. 13.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 32.

- ^ Bagnall 1999, p. 8.

- ^ Miles 2011, p. 240.

- ^ Lazenby 1996, p. 27.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 82, 311, 313–314.

- ^ Bagnall 1999, p. 237.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 55.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 56.

- ^ Sabin 1996, p. 64.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 57.

- ^ Sabin 1996, p. 66.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 98.

- ^ Lazenby 1996, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 104.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 100.

- ^ Tipps 1985, p. 435.

- ^ a b Casson 1995, p. 121.

- ^ a b Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 102–103.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 97, 99–100.

- ^ Murray 2011, p. 69.

- ^ Casson 1995, pp. 278–280.

- ^ de Souza 2008, p. 358.

- ^ a b Miles 2011, p. 178.

- ^ Wallinga 1956, pp. 77–90.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 100–101, 103.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 310.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 82.

- ^ Bagnall 1999, pp. 52–53.

- ^ a b Erdkamp 2015, p. 71.

- ^ a b Miles 2011, p. 179.

- ^ Miles 2011, pp. 179–180.

- ^ Bagnall 1999, pp. 64–66.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 97.

- ^ Bagnall 1999, p. 66.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 91–92, 97.

- ^ Miles 2011, pp. 180–181.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 109–110.

- ^ a b Bagnall 1999, p. 65.

- ^ Lazenby 1996, pp. 73–74.

- ^ Bagnall 1999, pp. 63–65.

- ^ Rankov 2015, p. 155.

- ^ Tipps 1985, pp. 435, 459.

- ^ Rankov 2015, pp. 155–156.

- ^ a b Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 110–111.

- ^ a b Lazenby 1996, p. 87.

- ^ a b Tipps 1985, p. 436.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 87.

- ^ Miles 2011, p. 188.

- ^ Tipps 2003, p. 382.

- ^ Tipps 1985, p. 438.

- ^ Miles 2011, p. 189.

- ^ Erdkamp 2015, p. 66.

- ^ Scullard 2006, p. 557.

- ^ Lazenby 1996, pp. 112, 117.

- ^ Scullard 2006, p. 559.

- ^ Lazenby 1996, pp. 114–116, 169.

- ^ Rankov 2015, p. 158.

- ^ Bagnall 1999, p. 80.

- ^ Miles 2011, pp. 189–190.

- ^ Lazenby 1996, p. 118.

- ^ a b Rankov 2015, p. 159.

- ^ Lazenby 1996, p. 169.

- ^ Miles 2011, p. 190.

- ^ Lazenby 1996, p. 127.

- ^ Bagnall 1999, pp. 84–86.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 117–121.

- ^ Bagnall 1999, pp. 88–91.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 121–122.

- ^ Rankov 2015, p. 163.

- ^ Bringmann 2007, p. 127.

- ^ a b c d e Lazenby 1996, p. 158.

- ^ a b c Scullard 2006, p. 565.

- ^ Bagnall 1999, p. 92.

- ^ Bagnall 1999, p. 91.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 131.

- ^ Lazenby 1996, p. 49.

- ^ a b Miles 2011, p. 196.

- ^ Bagnall 1999, p. 96.

- ^ Lazenby 1996, p. 157.

- ^ Scullard 2002, p. 178.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 128–129, 357, 359–360.

- ^ Bagnall 1999, pp. 112–114.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 133–134.

- ^ Eckstein 2017, p. 6.

- ^ a b Bagnall 1999, p. 115.

- ^ Bagnall 1999, p. 118.

- ^ Miles 2011, p. 208.

- ^ Eckstein 2017, p. 7.

- ^ Hoyos 2000, p. 377.

- ^ a b Scullard 2006, p. 569.

- ^ Miles 2011, pp. 209, 212–213.

- ^ Lazenby 1996, p. 175.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 136.

- ^ Bagnall 1999, p. 124.

- ^ a b Collins 1998, p. 13.

- ^ Hoyos 2015, p. 211.

- ^ Miles 2011, p. 213.

- ^ Miles 2011, pp. 226–227.

- ^ Hoyos 2015, p. 77.

- ^ Hoyos 2015, p. 80.

- ^ Miles 2011, p. 220.

- ^ Miles 2011, pp. 219–220, 225.

- ^ Eckstein 2006, pp. 173–174.

- ^ Miles 2011, pp. 222, 225.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 143–144.

- ^ a b Goldsworthy 2006, p. 144.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 144–145.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 145.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 310–311.

- ^ Briscoe 2006, p. 61.

- ^ Edwell 2015, p. 327.

- ^ Castillo 2006, p. 25.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 151.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 151–152.

- ^ a b Mahaney 2008, p. 221.

- ^ Bagnall 1999, pp. 161–162.

- ^ Fronda 2011, p. 252.

- ^ a b c d e Zimmermann 2011, p. 291.

- ^ Edwell 2015, p. 321.

- ^ Hoyos 2015b, p. 107.

- ^ Zimmermann 2011, pp. 283–284.

- ^ Bagnall 1999, p. 171.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 168.

- ^ Fronda 2011, p. 243.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 177–178.

- ^ Fronda 2011, pp. 243–244.

- ^ Bagnall 1999, pp. 175–176.

- ^ Bagnall 1999, pp. 175–176, 193.

- ^ a b Miles 2011, p. 270.

- ^ a b c Zimmermann 2011, p. 285.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 182.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 184.

- ^ Liddell Hart 1967, p. 45.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 189–190.

- ^ Fronda 2011, p. 244.

- ^ Lazenby 1998, p. 86.

- ^ Bagnall 1999, p. 183.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 195–196.

- ^ Bagnall 1999, pp. 184–188.

- ^ Zimmermann 2011, p. 286.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 199–200.

- ^ Bagnall 1999, pp. 191, 194.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 198–199.

- ^ Carey 2007, p. 64.

- ^ Fronda 2011, p. 245.

- ^ Bagnall 1999, pp. 192–194.

- ^ Miles 2011, p. 279.

- ^ Ñaco del Hoyo 2015, p. 377.

- ^ Carey 2007, p. 2.

- ^ Roberts 2017, pp. vi–1x.

- ^ a b Goldsworthy 2006, p. 227.

- ^ Lazenby 1998, pp. 94, 99.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 222–226.

- ^ Rawlings 2015, p. 313.

- ^ a b Lazenby 1998, p. 98.

- ^ Erdkamp 2015, p. 75.

- ^ Barceló 2015, p. 370.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 226.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 222–235.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 236.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 237–238.

- ^ Bagnall 1999, pp. 199–200.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 253–260.

- ^ a b Miles 2011, p. 288.

- ^ Edwell 2011, p. 327.

- ^ Bagnall 1999, p. 200.

- ^ Edwell 2011, p. 328.

- ^ a b Edwell 2011, p. 329.

- ^ Edwell 2011, p. 330.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 266–267.

- ^ Rawlings 2015, p. 311.

- ^ Zimmermann 2011, p. 290.

- ^ Miles 2011, pp. 304–306.

- ^ Bagnall 1999, pp. 286–287.

- ^ a b Miles 2011, p. 310.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 244.

- ^ Miles 2011, p. 312.

- ^ Bagnall 1999, p. 289.

- ^ a b Edwell 2011, p. 321.

- ^ a b c d e Edwell 2011, p. 322.

- ^ Coarelli 2002, pp. 73–74.

- ^ Etcheto 2012, pp. 274–278.

- ^ Miles 2011, pp. 268, 298–299.

- ^ a b c d e Edwell 2011, p. 323.

- ^ Zimmermann 2011, p. 292.

- ^ a b Barceló 2015, p. 362.

- ^ a b Edwell 2015, p. 323.

- ^ Carey 2007, pp. 86–90.

- ^ Bagnall 1999, p. 211.

- ^ Zimmermann 2011, p. 293.

- ^ Miles 2011, p. 303.

- ^ Edwell 2011, p. 333.

- ^ Barceló 2015, p. 372.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 286–288.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 291–292.

- ^ Bagnall 1999, pp. 282–283.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 298–300.

- ^ Bagnall 1999, pp. 287–291.

- ^ a b Goldsworthy 2006, p. 302.

- ^ a b Miles 2011, p. 315.

- ^ Carey 2007, p. 119.

- ^ Bagnall 1999, pp. 291–293.

- ^ Lazenby 1996, p. 179.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 308–309.

- ^ Eckstein 2006, p. 176.

- ^ Miles 2011, p. 318.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 359–360.

- ^ Kunze 2015, p. 398.

- ^ Kunze 2015, pp. 398, 407.

- ^ a b c Kunze 2015, p. 407.

- ^ Kunze 2015, p. 408.

- ^ Le Bohec 2015, p. 434.

- ^ Le Bohec 2015, pp. 436–437.

- ^ Le Bohec 2015, p. 438.

- ^ Bagnall 1999, pp. 309–310.

- ^ Coarelli 1981, p. 187.

- ^ Le Bohec 2015, p. 439.

- ^ a b c Miles 2011, p. 343.

- ^ Bagnall 1999, p. 314.

- ^ Bagnall 1999, p. 315.

- ^ a b c Le Bohec 2015, p. 440.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 348–349.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 349.

- ^ Bagnall 1999, p. 318.

- ^ Miles 2011, p. 2.

- ^ a b Le Bohec 2015, p. 441.

- ^ Miles 2011, p. 346.

- ^ a b Miles 2011, p. 3.

- ^ Miles 2011, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Scullard 2002, p. 316.

- ^ Ridley 1986, pp. 144–145.

- ^ Baker 2014, p. 50.

- ^ Scullard 2002, pp. 310, 316.

- ^ Whittaker 1996, p. 596.

- ^ Pollard 2015, p. 249.

- ^ Fantar 2015, pp. 455–456.

- ^ Richardson 2015, pp. 480–481.

- ^ Miles 2011, pp. 363–364.

- ^ Mazzoni 2010, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 296.

- ^ UNESCO 2020.

Sources

- Bagnall, Nigel (1999). The Punic Wars: Rome, Carthage and the Struggle for the Mediterranean. London: Pimlico. ISBN 978-0-7126-6608-4.

- Baker, Heather D. (2014). "'I burnt, razed (and) destroyed those cities': The Assyrian accounts of deliberate architectural destruction". In Mancini, JoAnne; Bresnahan, Keith (eds.). Architecture and Armed Conflict: The Politics of Destruction. New York: Routledge. pp. 45–57. ISBN 978-0-415-70249-2.

- Barceló, Pedro (2015) [2011]. "Punic Politics, Economy, and Alliances, 218–201". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley. pp. 357–375. ISBN 978-1-119-02550-4.

- Le Bohec, Yann (2015) [2011]. "The "Third Punic War": The Siege of Carthage (148–146 BC)". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley. pp. 430–446. ISBN 978-1-1190-2550-4.

- Bringmann, Klaus (2007). A History of the Roman Republic. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Polity Press. ISBN 978-0-7456-3370-1.

- Briscoe, John (2006). "The Second Punic War". In Astin, A. E.; Walbank, F. W.; Frederiksen, M. W.; Ogilvie, R. M. (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History: Rome and the Mediterranean to 133 B.C. Vol. VIII. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 44–80. ISBN 978-0-521-23448-1.

- Carey, Brian Todd (2007). Hannibal's Last Battle: Zama & the Fall of Carthage. Barnslet, South Yorkshire: Pen & Sword. ISBN 978-1-84415-635-1.

- Casson, Lionel (1995). Ships and Seamanship in the Ancient World. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-5130-8.

- Castillo, Dennis Angelo (2006). The Maltese Cross: A Strategic History of Malta. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-32329-4.

- Champion, Craige B. (2015) [2011]. "Polybius and the Punic Wars". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley. pp. 95–110. ISBN 978-1-1190-2550-4.

- Coarelli, Filippo (1981). "La doppia tradizione sulla morte di Romolo e gli auguracula dell'Arx e del Quirinale". In Pallottino, Massimo (ed.). Gli Etruschi e Roma : atti dell'incontro di studio in onore di Massimo Pallottino : Roma, 11-13 dicembre 1979 (in Italian). Rome: G. Bretschneider. pp. 173–188. ISBN 978-88-85007-51-2.

- Coarelli, Filippo (2002). "I ritratti di 'Mario' e 'Silla' a Monaco e il sepolcro degli Scipioni". Eutopia Nuova Serie (in Italian). II (1): 47–75. ISSN 1121-1628.

- Collins, Roger (1998). Spain: An Oxford Archaeological Guide. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-285300-4.

- Curry, Andrew (2012). "The Weapon That Changed History". Archaeology. 65 (1): 32–37. JSTOR 41780760.

- Eckstein, Arthur (2006). Mediterranean Anarchy, Interstate War, and the Rise of Rome. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24618-8.

- Eckstein, Arthur (2017). "The First Punic War and After, 264–237 BC". The Encyclopedia of Ancient Battles. Wiley Online Library. pp. 1–14. doi:10.1002/9781119099000.wbabat0270. ISBN 978-1-4051-8645-2.

- Edwell, Peter (2011). "War Abroad: Spain, Sicily, Macedon, Africa". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley. pp. 320–338. ISBN 978-1-119-02550-4.

- Edwell, Peter (2015) [2011]. "War Abroad: Spain, Sicily, Macedon, Africa". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley. pp. 320–338. ISBN 978-1-119-02550-4.

- Erdkamp, Paul (2015) [2011]. "Manpower and Food Supply in the First and Second Punic Wars". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley. pp. 58–76. ISBN 978-1-1190-2550-4.

- Etcheto, Henri (2012). Les Scipions. Famille et pouvoir à Rome à l'époque républicaine (in French). Bordeaux: Ausonius Éditions. ISBN 978-2-35613-073-0.

- Fantar, M’hamed-Hassine (2015) [2011]. "Death and Transfiguration: Punic Culture after 146". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley. pp. 449–466. ISBN 978-1-1190-2550-4.

- Fronda, Michael P. (2011). "Hannibal: Tactics, Strategy, and Geostrategy". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 242–259. ISBN 978-1-405-17600-2.

- Goldsworthy, Adrian (2006). The Fall of Carthage: The Punic Wars 265–146 BC. London: Phoenix. ISBN 978-0-304-36642-2.

- Hau, Lisa (2016). Moral History from Herodotus to Diodorus Siculus. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-1-4744-1107-3.

- Hoyos, Dexter (2000). "Towards a Chronology of the 'Truceless War', 241–237 B.C.". Rheinisches Museum für Philologie. 143 (3/4): 369–380. JSTOR 41234468.

- Hoyos, Dexter (2015) [2011]. A Companion to the Punic Wars. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley. ISBN 978-1-1190-2550-4.

- Hoyos, Dexter (2015b). Mastering the West: Rome and Carthage at War. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-986010-4.

- Koon, Sam (2015) [2011]. "Phalanx and Legion: the "Face" of Punic War Battle". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley. pp. 77–94. ISBN 978-1-1190-2550-4.

- Jones, Archer (1987). The Art of War in the Western World. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-01380-5.

- Kunze, Claudia (2015) [2011]. "Carthage and Numidia, 201–149". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley. pp. 395–411. ISBN 978-1-1190-2550-4.

- Lazenby, John (1996). The First Punic War: A Military History. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-2673-3.

- Lazenby, John (1998). Hannibal's War: A Military History of the Second Punic War. Warminster: Aris & Phillips. ISBN 978-0-85668-080-9.

- Liddell Hart, Basil (1967). Strategy: The Indirect Approach. London: Penguin. OCLC 470715409.

- Mahaney, W.C. (2008). Hannibal's Odyssey: Environmental Background to the Alpine Invasion of Italia. Piscataway, New Jersey: Gorgias Press. ISBN 978-1-59333-951-7.

- Mazzoni, Cristina (2010). "Capital City: Rome 1870–2010". Annali d'Italianistica. 28: 13–29. JSTOR 24016385.

- Miles, Richard (2011). Carthage Must be Destroyed. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-101809-6.

- Mineo, Bernard (2015) [2011]. "Principal Literary Sources for the Punic Wars (apart from Polybius)". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley. pp. 111–128. ISBN 978-1-1190-2550-4.

- Murray, William (2011). The Age of Titans: The Rise and Fall of the Great Hellenistic Navies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-993240-5.

- Pollard, Elizabeth (2015). Worlds Together Worlds Apart. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-92207-3.

- Ñaco del Hoyo, Toni (2015) [2011]. "Roman Economy, Finance, and Politics in the Second Punic War". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley. pp. 376–392. ISBN 978-1-1190-2550-4.

- Rankov, Boris (2015) [2011]. "A War of Phases: Strategies and Stalemates". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley. pp. 149–166. ISBN 978-1-4051-7600-2.

- Rawlings, Louis (2015) [2011]. "The War in Italy, 218–203". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley. pp. 58–76. ISBN 978-1-1190-2550-4.

- Richardson, John (2015) [2011]. "Spain, Africa, and Rome after Carthage". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley. pp. 467–482. ISBN 978-1-1190-2550-4.

- Ridley, Ronald (1986). "To Be Taken with a Pinch of Salt: The Destruction of Carthage". Classical Philology. 81 (2): 140–146. doi:10.1086/366973. JSTOR 269786. S2CID 161696751.

- Roberts, Mike (2017). Hannibal's Road: The Second Punic War in Italy 213–203 BC. Pen & Sword: Barnsley, South Yorkshire. ISBN 978-1-47385-595-3.

- Rosselló Calafell, Gabriel. Relaciones exteriores y praxis diplomática cartaginesa. El periodo de las guerras púnicas. Prensas de la universidad de Zaragoza. ISBN 9788413405513.

- Sabin, Philip (1996). "The Mechanics of Battle in the Second Punic War". Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies. Supplement. 41 (67): 59–79. doi:10.1111/j.2041-5370.1996.tb01914.x. JSTOR 43767903.

- Scullard, Howard H. (2002). A History of the Roman World, 753 to 146 BC. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-30504-4.

- Scullard, Howard H. (2006) [1989]. "Carthage and Rome". In Walbank, F. W.; Astin, A. E.; Frederiksen, M. W. & Ogilvie, R. M. (eds.). Cambridge Ancient History: Volume 7, Part 2, 2nd Edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 486–569. ISBN 978-0-521-23446-7.

- Shutt, Rowland (1938). "Polybius: A Sketch". Greece & Rome. 8 (22): 50–57. doi:10.1017/S001738350000588X. JSTOR 642112. S2CID 162905667.

- Sidwell, Keith C.; Jones, Peter V. (1998). The World of Rome: an Introduction to Roman Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-38600-5.

- de Souza, Philip (2008). "Naval Forces". In Sabin, Philip; van Wees, Hans & Whitby, Michael (eds.). The Cambridge History of Greek and Roman Warfare, Volume 1: Greece, the Hellenistic World and the Rise of Rome. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 357–367. ISBN 978-0-521-85779-6.

- Tipps, G.K. (1985). "The Battle of Ecnomus". Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte. 34 (4): 432–465. JSTOR 4435938.

- Tipps, G. K. (2003). "The Defeat of Regulus". The Classical World. 96 (4): 375–385. doi:10.2307/4352788. JSTOR 4352788.

- "Archaeological Site of Carthage". UNESCO. 2020. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- Walbank, F.W. (1990). Polybius. Vol. 1. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-06981-7.

- Wallinga, Herman (1956). The Boarding-bridge of the Romans: Its Construction and its Function in the Naval Tactics of the First Punic War. Groningen: J.B. Wolters. OCLC 458845955.

- Warmington, Brian (1993) [1960]. Carthage. New York: Barnes & Noble, Inc. ISBN 978-1-56619-210-1.

- Whittaker, C. R. (1996). "Roman Africa: Augustus to Vespasian". In Bowman, A.; Champlin, E.; Lintott, A. (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. X. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 595–96. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521264303.022. ISBN 978-1-139-05438-6.

- Zimmermann, Klaus (2011). "Roman Strategy and Aims in the Second Punic War". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Oxford: John Wiley. pp. 280–298. ISBN 978-1-405-17600-2.