Flag on Prospect Hill debate

| Part of a series on the |

| American Revolution |

|---|

|

|

|

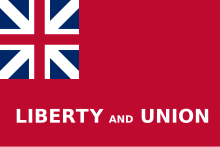

According to tradition, the first flag of the United States, the Grand Union Flag ("Continental Colours"), was raised by General George Washington at Prospect Hill in Somerville, Massachusetts, on 1 January 1776, in an attempt to raise the morale of the men of the Continental Army. There was a 76-foot liberty pole situated on Prospect Hill on 22 August 1775 that "was visible from most parts of the American lines, as well as from Boston".[1][note 1] The standard account has been questioned by modern researchers most notably Peter Ansoff, who in 2006 published a paper entitled "The Flag on Prospect Hill" where he advances the argument that Washington flew the Union Jack ("British Union Flag") and not the Continental Colours that bears 13 stripes.[3] Others, such as Byron DeLear, have argued in favour of the traditional version of events.[4][5][6]

There is a Prospect Hill Monument that was erected in 1903[7][note 2] and annual flag-raising ceremonies involving American Revolutionary War reenactors are held at Prospect Hill on New Year's Day.[9]

Background

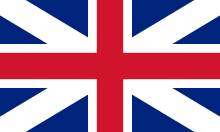

The British Union Flag featuring the crosses of Saint George and Saint Andrew was introduced in 1606 to symbolise the dual status of King James I as ruler of England and Scotland. It was flown at sea as a maritime flag and from forts and royal castles. It formed the basis of the "King's colours" bestowed on army regiments. In 1801, the red cross of Saint Patrick was added to herald Ireland's entry into the United Kingdom. Beginning in the 19th century, it achieved customary use as the UK national flag when it was "inscribed with slogans as a protest flag of the Chartist movement".[8][10]

The American revolutionaries continued to associate the British Union Flag with their cause before and after hostilities between the UK and the Thirteen American colonies erupted in April 1775 with the battles of Lexington and Concord.[12][note 3] Colonial propaganda generally made the distinction between the Crown, to which most colonists still remained loyal, and the parliament and the parliamentary executive, which was viewed as the cause of their grievances.[18] This sentiment finds expression in a verse affixed to the flag pole in Taunton, Massachusetts that mentions:

... Zeal for the Preservation of Their Rights as Men and American Englishmen ... Resentment of The Wrongs and Injuries offered to the English colonies in general, and This Province in particular ... Through unjust Claims of A British Parliament and the Machiaveilan Policy of a British Ministry ... [18][note 4]

The reference to "the English colonies in General" points to the way the British Union Flag was seen as a protest symbol in that "its very name hinted at the idea of a union among the colonies" being "a concept that was not viewed favorably in London".[19] Its use by the American revolutionaries was "in a sense a challenge to authority" as the concept of a national flag that represents both the government and the people is modern and did not prevail in the 18th century.[19]

In a speech given on 27 October 1775 at the opening of parliament, copies of which reached Boston by the end of December 1775, King George III "made it clear that he had no sympathy for the distinctions made by the colonists"[20] stating:

... [the colonies] now openly avow their revolt, hostility, and rebellion. They have raised troops, are collecting a naval force; they have seized public revenue, and assumed to themselves legislative, executive, and judicial powers. .. The authors and promoters of this deliberate conspiracy ... meant only to amuse by vague expressions of attachment to the Parent State, and the strongest protestations of loyalty to me, while they were preparing for a general revolt.[20]

The Continental Congress appointed George Washington as the commander-in-chief of the Continental Army on 15 June 1775 and dispatched him to Boston, where the British were under siege, to assume command of what he called "the Troops of the United Provinces of North America". He arrived at his post shortly after the Battle of Bunker Hill.[21]

It is not known for certain when the Continental Colours was designed or by whom. The design is nearly identical to the Flag of the British East India Company that was chartered in England in 1600 and played a pivotal role in the Boston Tea Party at the beginning of the American Revolution.[22][note 5] It was raised for the first recorded time aboard the USS Alfred on 3 December 1775 by Senior Lieutenant John Paul Jones who referred to it as the "Flag of Freedom" and the "Flag of America".[24] Construction of the specimen flown from the Alfred has been credited to Margaret Manny.[25] The Continental Colours were in use until late 1777.[26]

Arguments for the British Union Flag

All three known eyewitness accounts of the flag raising on Prospect Hill state that it was the "Union Flag". Peter Ansoff posits that the terms "Grand Union" and "Great Union" were not in use during the American Revolution "but were retrospectively applied to the striped union flag by 19th century historians".[7]

Primary sources

George Washington's letter to his friend and aide-de-camp Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Reed, dated 4 January 1776, states that:

...we had hoisted the Union Flag in compliment to the United Colonies; but behold! it was received in Boston as a token of the deep impression the Speech had made upon us, and as a signal of submission, so we learn by a person out of Boston last night. By the time, I presume, they begin to think it strange that we have not made a formal surrender of our lines. [...][27]

There appears to be no reason arising from Washington's words or the context to doubt that he was referring to anything other than the British Union Flag and that what he was conveying to Reed "was the irony of the Army's hoisting a symbol of the Crown just before receiving the King's message of hostility toward the colonies".[27] The Continental Colors was devised in Philadelphia for use by the nascent Continental Navy. At the time of the flag raising on Prospect Hill, it had never been formally adopted, and Washington may not have even been aware of the existence of the Continental Colors by then, which is not mentioned in any of his voluminous correspondence with the Continental Congress in the period July to December 1775.[27]

The second account comes from an anonymous captain of a British merchant ship that arrived in Boston on 1 January 1776. In a lengthy letter to the ship owners dated 17 January 1776, he states:

I can see the Rebels' camp very plain, whose colours, a little while ago, were entirely red;[note 6] but, on the receipt of the King's speech, (which they burnt,) they have hoisted the Union Flag, which is here supposed to intimate the union of the Provinces.[30]

Ansoff notes that his correspondents in London would have no knowledge of the Continental Colours and that if the flag raised on Prospect Hill differed from the British Union Flag, "it seems likely the captain would have further described it".[31] The anonymous author makes the same assumption Washington believed the British had made being "that raising the King's colours was a reaction to the King's speech".[31] However, whereas Washington had suggested to Reed in jest that it was interpreted as a sign of submission, the captain saw it as signalling colonial unity instead.[31]

There is a third eyewitness account contained in a letter by British Lieutenant William Carter of the 40th Regiment of Foot dated 26 January 1776, which states:

The King's speech was sent by a flag [of truce] to them on the 1st instant. In a short time after they received it, they hoisted a union flag (above the continental with the thirteen stripes) at Mount Pisga;[note 7] their citadel fired thirteen guns, and gave the like number of cheers.[31]

Unlike the other eyewitness accounts, Carter refers to "thirteen stripes" although he does not specify whether they are horizontal or vertical. According to Ansoff, "it seems fairly clear from his phrasing that he is talking about a Union Flag flying above another, striped flag". He speculates that if there was a flag hoisted beneath the British Union Flag, it may have been "one of the signal flags that were commonly flown on Prospect Hill". Amid the salutes and cheers, Carter may have assumed it was designed to represent the colonies. Washington may have "failed to mention it as it was not pertinent to the point he was making to Reed". Ansoff concedes that Carter may have been "giving a muddled description of a single flag with both the union crosses and thirteen stripes". However, if so, he considers it "extremely unlikely" that Washington and the anonymous ship captain would have referred to it as the Union Flag without any further qualification.[31]

Secondary sources

There are two secondary accounts that are frequently cited in the vexillological literature. The first appeared on 15 January 1776 in Philadelphia's Dunlap's Pennsylvania Packet or the General Advertiser which states:

Our advices conclude with the following anecdote:-That upon the King's Speech arriving in Boston, a great number of them were reprinted and sent out to our lines on the 2nd of January, which being also the day of forming the new army, the great Union Flag was hoisted on Prospect Hill, in compliment to the United Colonies.-this happening soon after the Speeches were delivered at Roxbury, but before they were received at Cambridge, the Boston gentry supposed it to be a token of the deep impression the Speech had made, and a signal of submission-That they were much disappointed at finding several days elapse without some formal measure leading to a surrender, with which they had begun to flatter themselves.[32]

Ansoff thinks it "very likely" the author has Washington's letter to Reed available to them given the similarity in phrasing. It appears that it was not uncommon for private correspondence to form the basis of newspaper articles and Washington complained about this in a previous letter to Reed. Ansoff believes that this account is the source of the term "Great Union" that historians subsequently used as the name for the striped Continental Colours.[33]

There was another secondary account that appeared in the 1776 edition of the British publication The Annual Register that states:

The arrival of a copy of the King's speech, with an account of the fate of the petition from the continental congress, is said to have excited the greatest degree of rage and indignation among them; as a proof of which, the former was publicly burnt in the camp; and they are said upon this occasion to have changed their colours, from a plain ground, which they had hitherto used, to a flag with thirteen stripes, as a symbol of the number and union of the colonies".[33]

Although this account refers to a "flag with thirteen stripes", Ansoff points out that "it is not an original account". It was not published until 25 September 1777 which was "long after the striped Continental Flag had become known to the British" and by which time it "had been superseded by the stars and stripes". The plain ground changing to a field of thirteen stripes faithfully "recalls the transition from the British red ensign to the American Continental colors". Absent is any reference to the Union Flag and Ansoff concludes that the editors "probably conflated this with accounts of the event at Prospect Hill".[33]

Origin of the terms "Great Union" and "Grand Union"

Ansoff asserts the idea that the Continental Colours was raised on Prospect Hill had originated in a footnote in a history of the Siege of Boston published by Richard Frothingham in 1849. The relevant extract which relies on several previous primary sources states that:

Another flag alluded to in 1775 [sic], called "The Union Flag" … Washington (Jan. 4) states … that it was raised in compliment to the United Colonies. Also, that without knowing or intending it, it gave great joy to the enemy, as it was regarded as a response to the king's speech. The Annual Register (1776) says the Americans, so great was their rage and indignation, burnt the speech and "charged their colors from a plain red ground, which they had hitherto used, to a flag with thirteen stripes, as a symbol of the number and union of the colonies". Lieut. Carter, however, is still a better authority for the device on the union flag. He was on Charlestown Heights, and says, January 26: "The king's speech was sent by a flag to them on the 1st instant. In a short time after they received it, they hoisted a union flag (above a continental with thirteen stripes) at Mount Pisgah; their citadel fired thirteen guns, and gave the like number of cheers." This union flag also was hoisted at Philadelphia in February, when the American fleet sailed under Admiral Hopkins.[note 8] A letter says that it sailed 'amidst the acclamations of thousands assembled on the joyful occasion, under the display of a union flag, with thirteen stripes in the field, emblematical of the thirteen united colonies".[35]

Schuyler Hamilton reinforces the idea that a singular flag was flown on Prospect Hill in his 1853 history of the American flag. Quoting Carter's letter Hamilton remarks:

... we may expect inaccuracies in the description of a flag newly presented to [British observers], and which, even to an offer on Charlestown Heights, who, appears, was at some pains to describe it, appeared to be two flags … [34]

Hamilton also refers to a Philadelphia newspaper account dated 15 January 1776 that used the term "Great Union Flag" stating:

We observe [that] … in the extract from the newspaper account of this, that the flag was displayed on Prospect Hill, and that it must have been a peculiarly marked Union flag, to be called the Great Union Flag. As this was the name given to the national banner of Great Britain, this indicates this flag as the national banner of the United Colonies … they were British colonies: and, as we have shown, they used the British Union but now, they were to distinguish their flag by its color would naturally be suggested as being striking, as enabling them to show the number and union of the colonies … Hence, probably the name The Great Union Flag, given to it by the writer in the Philadelphia Gazette, before quoted … indicated, as respecting the Colonies, precisely what the Great Union Flag of Great Britain indicated respecting the mother country.[36]

Ansoff notes that it is "somewhat misleading" for Hamilton to say that "Great Union Flag" was the "name given to the national banner of Great Britain". The term "great union" is found in a 1768 royal warrant concerning the colours carried by British infantry regiments and applies "generically to the design of the combined English and Scottish crosses, rather than to a particular flag". The reference in the newspaper report to the "great union" flag is probably a description rather than the name of the flag and "supports the idea that it was a union flag with the combined English and Scottish crosses overall".[37] Hamilton's statement that the flag raised on Prospect Hill "must have been a peculiarly marked Union flag, to be called the Great Union Flag" is unsubstantiated yet his "use of the term as a proper name has been perpetuated by later historians, and is often used to refer to the Continental Colors".[38]

According to Ansoff's 2006 paper, the first reference to the Continental Colours as the "Grand Union" comes from page 218 of the 1872 first edition of George Preble's History of the Flag of the United States of America, which states:

A letter from Boston, in the 'Pennsylvania Gazette,' says "The grand union was raised on the 2d, in compliment to the United Colonies".[38]

He stated that Preble evidently substitutes the word "grand" for "great" which appeared in the letter published in the Pennsylvania Gazette on 17 January 1776 and given his work is accepted as the seminal history of the American flag "his mistake has been perpetrated in vexillological and general literature ever since".[38]

However, in his response to Byron DeLear in 2015, Ansoff makes a correction that the first recorded use of the term "Grand Union" is actually by historian Thompson Westcott in 1852. Responding to a query Westcott states:

A letter from Boston ... published in the Penna Gazette for January 1776, says: 'The grand union flag was raised on the 2nd (of January) in compliment to the united colonies.'[39]

Ansoff says this "almost certainly" refers to the account in the Pennsylvania Gazette, with the word "grand" accidentally used in place of "great". Preble then cites Westcott as a source "and probably copied the quote without checking it against the original".[40]

Arguments for the Continental Colours

Byron DeLear has argued in favour of the conventional history based on a review of "eighteenth-century linguistic standards, contextual historical trends, and additional primary and secondary sources".[41]

Continental Colours as a "Union Flag"

In his 2014 paper "Revisiting the Flag at Prospect Hill: Grand Union or Just British", DeLear lists a number of additional primary sources where the Continental Colours are contemporaneously referred to using the descriptor "union".

Dated between December 1775 and March 1776[42] they are:

- "Union Flag" (Account book of Philadelphia ship chandler, James Wharton, 12 December 1775)[43]

- "UNION FLAG of the American States" (The Virginia Gazette, 17 May 1776)[44]

- "Union flag, and striped red and white in the field" (Letter to Delegates to Congress from Richard Henry Lee, 5 January 1776)[45][note 9]

- "Continental Union Flag" (Resolution of the Convention of Virginia, 11 May 1776, published in the Virginia Gazette, 18 May 1776 edition)[47]

- "1 Union Flag 13 Stripes Broad Buntg and 33 feet fly" (Bill for purchase of Continental Colours as itemised in James Wharton's day book, 8 February 1776)[48]

- "union flag with thirteen stripes in the field emblematical of the thirteen United Colonies" (Account of sailing of the first American fleet, Newborn [sic], 9 February 1776)[49]

- "a Continental Union Flag" (The Virginia Gazette, 20 April 1776)[50]

- "striped under the union with thirteen strokes" (Taken from several publications in different forms between March and July 1776)[51]

DeLear cites further primary sources that show the term "union flag" also being applied to the British red, blue and white ensigns that all bear the British Union Flag in the canton.[21] He argues that it was suitable for Washington and others to have referred to the Continental Colours in this way, given that "At the time of the introduction of the new striped union flag was the best abbreviated way to describe it".[52] The three contemporary accounts cited by Ansoff might have been prompted by "the most prominent feature of the flag, the British Union Jack or by the thirteen stripes intimating the union of the colonies-or both".[21] It is possible that Washington chose to employ the term "union" for a different reason than the other two, British eyewitnesses.[21]

Ansoff has subsequently replied that DeLear has misrepresented the evidence of 18th-century use of the term "union flag".[53] He notes that in seven of the eight examples given by DeLear, "the writer qualified his description to make it clear that he was not referring to a normal British union flag, but to an 'American' or 'Continental' version and/or one that contained stripes".[54] In relation to the Wharton account book entry of 12 December 1775 that refers to a "Union Flag" without any further qualification, Ansoff cites a later invoice dated 23 December 1775 that "lists delivery to the Columbus of "1 Ensign 18 feet by 30" that "was presumably the Continental Colors for that vessel". Ansoff believes "It is quite likely that the flag mentioned in DeLear's citation was a normal British union flag, or possibly a British red ensign" noting it was a "common practice in the eighteenth century for warships to carry flags of potential opponents for deceptive purposes".[55] Ansoff asserts that DeLear's implication the term "union flag" is "strictly modern" is questionable. He says it was more prevalent in the 18th century than it is in modern times where the term "Union Jack" is frequently used.[56]

When did Washington know about the Continental Colours?

Concerning Ansoff's assertion that Washington "was probably not aware" of the Continental Colours that were unofficial at the time he wrote to Reed and were solely for "use by the embryonic Continental Navy", DeLear asserts that given the lack of direct evidence of its origins, the original purpose of the Continental Colours should not be narrowly confined to a maritime role. The Continental Colours was used as the garrison flag at Fort Mifflin in February 1776 and was hoisted by American forces at New York in July 1776.[57] Whilst there is no direct evidence it was officially adopted prior to the flag-raising ceremony on Prospect Hill "its promulgation throughout the colonies is self-evident".[57][note 10] The earliest known British reference to the Continental Colours is a letter by a British informer to Lord Dartmouth dated 20 December 1775.[61] British spy James Brattle makes a detailed report on the Continental Navy dated 4 January 1776. He described the new Continental Colours as "English Colours But More Striped".[62] In a message to Sir Grey Cooper dated 10 January 1776 a British spy in Philadelphia Gilbert Barkly, refers to the Continental Colours as being "what they call the Ammerican flag".[63] DeLear states that at the very least "it is not too far of a stretch to presume-at the very least-that knowledge of that flag (and what it evidently represented) had passed from Philadelphia to Cambridge among principals of the American war effort".[64] It was a stage in the American Revolution amid escalating British violence "with ships and stores seized, forts captured, and cities burned".[65] DeLear argues that "notions of nationhood were clearly maturing in this exact time and space" and notes the earliest surviving documentary evidence of the term "United States of America" was written at Washington's headquarters just after the New Year's Day flag raising ceremony.[66][note 11] DeLear notes that the latest example provided by Ansoff of the American revolutionaries still identifying with the British Union Flag is the diary entry of the British officer based in Boston dated 1 May 1775, after the battles of Lexington and Concord, but "before the bloody escalation at Bunker Hill". Along with Washington being commissioned as the army commander in chief, these were "two developments that necessitated heightened levels of military discipline, seriousness, and formality". DeLear compares the "relatively ad hoc manner" of such displays, as cited by Ansoff, with the ceremonies when the Continental Colours debuted aboard the Alfred or the flag-raising on Prospect Hill.[67] Coming soon after the inauguration of the Continental Navy, DeLear maintains it would have been "wholly uncharacteristic" for Washington to hoist the British Union Flag to mark the establishment of the Continental Army.[68][note 12] In what became later known as the "Revolutionary Year" the New Year's Day ceremony was the "perfect opportunity" to unveil the Continental Colours.[69] DeLear says "it seems unimaginable that he would fly the enemy's colors on this historic occasion".[68] Historian Pauline Maier concurs, stating "You wouldn't want a flag that was the same flag as the people [you were fighting]".[70] That it had achieved customary use as the national flag of the thirteen American colonies was amply demonstrated in October and November 1776 when Denmark and the United Netherlands became the first respective foreign nations to perform a gun salute upon a ship wearing the Continental Colours entering port.[71]

Ansoff says that DeLear's analysis of the primary sources ignores key contextual factors firstly being the official stance of the United Colonies with regards to the King and the parliamentary executive and secondly Washington's propensity to follow the lead of the Congress in regards to political matters.[72]

Joseph Reed authored an earlier flag directive

Reed is the author of one of the few known flag directives of the period in a message to Colonel John Glover and Stephen Moylan dated 20 October 1775. He suggests the Pine Tree Flag be used so that "our vessels may know one another" describing the "particular colour" as being a flag "with a white ground, a Tree in the Middle, the motto (Appeal to Heaven)[.] This is the Flag of our floating Batteries".[73] This reveals that Washington and Reed did concern themselves with deciding what flags the Continental forces were flying. When Washington relayed the news of the Prospect Hill flag-raising ceremony to his aide-de-camp, "it can be safely assumed that Reed knew to what Washington was referring to" and that "Their close working relationship on these matters may have obviated the need for additional clarifying detail".[74] In his Standards and Colors of the American Revolution, flag historian Edward W. Richardson states that Washington does not describe the flag to Reed and "He speaks of it only as 'the union flag' which indicates that Reed knew the design".[75]

Washington, in his surviving letters to Reed, mentions additional prior correspondence, the whereabouts of which are unknown. His personal secretary was Tobias Lear V, who served Washington from 1784-1799 and was there to record his famous last words, "tis well". Lear has been accused of mishandling Washington's papers, for which he had custody for a year after Washington's death. Supreme Court Justice John Marshall then took possession of these documents from Lear after volunteering to write a biography of Washington. Marshall eventually discovered that "swaths of Washington's diary were missing, especially sections during the war and presidency, and that a handful of key letters has also vanished". In a letter to Marshall, Lear denied culling any of Washington's papers. However, in a letter to Alexander Hamilton, he refutes his own denial. "There are as you well know," Lear states, "among the several letters and papers, many which every public and private consideration should withhold from further inspection". Lear asks Hamilton if there are any documents of military significance that he would like removed. DeLear speculates that among "the twelve missing Reed letters from November to December 1775" and other items from Washington's archives that "may have been suppressed" there could "very plausibly" have been more information about the origin and proclamation of the Continental Colours.[76]

Other primary and secondary sources

DeLear finds Lieutenant Carter's eyewitness account illuminating as it is the only primary source that mentions a flag with thirteen stripes. Carter said that "they hoisted an union flag (above the continental with the thirteen stripes)" at Prospect Hill. As opposed to Ansoff who takes it to refer to two separate flags, DeLear gives contemporary examples where such terms were used as a "positioning convention" where the field of a flag is seen as below the canton or upper hoist quarter to argue that it refers to a single flag being the Continental Colours.[note 13] In any case Ansoff says that Carter's description is "the earliest known reference to a striped Continental flag in the Boston area" a month after the flag raising ceremony on the Alfred.[78] Ansoff acknowledges that "Carter's description is undeniably ambiguous" and that, taken on its own, there "would be a stronger case that the flag might actually have been the Continental Colors". However, Ansoff argues that "the cumulative evidence provided by all three [primary] accounts would appear to make this unlikely".[79] Carter did not publish his letter until 1784 when the war was over and Ansoff thinks "It is conceivable that he edited them retroactively to include information that was common knowledge by then".[53]

DeLear concludes that in addition to all modern accounts of the event on Prospect Hill that have the Continental Colours flying there, all secondary sources "report the same conventional history, and, if erroneous, nowhere were they later corrected until Ansoff".[74][note 14]

See also

- Eureka Jack Mystery, debate over flag arrangements at the Eureka Stockade

- Prospect Hill (Massachusetts)

- Prospect Hill Monument

Notes

- ^ The flag pole on Prospect Hill was previously a mast taken from the British schooner HMS Diana following the Battle of Chelsea Creek on 27–28 May 1775.[2]

- ^ The Prospect Hill Monument has a plaque that reads: "From this aminence on January 1, 1776 The flag of the United Colonies Bearing thirteen stripes and the crosses of Saint George and Saint Andrew First waved defiance to a foe".[8]

- ^ The diary of Boston merchant John Rowe has an entry dated 14 August 1767 that states: "This day the Colours were displayed on the Tree of Liberty abt. Sixty Peopls Sons of Liberty met One of Clock & drank the King's Health ..." Then on 22 August 1767, he says, "Spent the Afternoon at the Ware-house & at Clarks Wharf. Mr. Hancocks Union Flagg was hoisted for the first time..."[8] George Preble mentions that British Union Flags were raised over a tent in Boston where a company had "assembled to celebrate the anniversary of the Stamp Act in 1773",[13] "on sleds carrying wood for the inhabitants of Boston in January 1775",[14] "in New York in March 1775", and "on a Liberty Pole in Savannah on 19 June 1775".[15] Preble comments that "No description of the union flags of these times has been preserved ... nevertheless, it is more than probable, and almost certain, that these flags were the familiar flags of the English and Scotch union ... and long known as union flags, inscribed with various popular and patriotic mottoes". Ansoff notes that he had not been able to verify Preble's sources.[16] The diary of a British officer in Boston dated 1 May 1775 states: "The Congress that's sitting at Concord has resolved to have an Army of 13000 Men … The Rebels have erected the Standard at Cambridge; they call themselves the King's Troops and us the Parliaments. Pretty Burlesque!"[17]

- ^ In the Boston Evening Post, 24 October 1774 edition, it was reported that intelligence had been received from Taunton "that on Friday last a Liberty Pole 112 Feet long was raised there, on which is a Vane, and a Union Flag flying, with the Words LIBERTY and UNION thereon..."[8] Ansoff disputes the traditional rendering of the Taunton flag as a defaced British red ensign. He notes that the newspaper description simply refers to it as a "union flag" and that the word "and" not being capitalised suggests it was not featured on the original Taunton flag. Ansoff states that it "seems reasonable" the Taunton flag followed a similar pattern to the British Union Flag in a well-known engraving of the battle of Lexington where the horizontal arm of the Saint George's cross bears the word "Liberty".[11]

- ^ DeLear makes a circumstantial case the two flags are related based on the "business interests and connections" between Robert Morris, Benjamin Franklin and key principals of the East India Company who "were in business together before and after the revolution" that "would at least seem to indicate the possibility of shared interest". The symbolism of the British East India Company "may have been seen as a desirable and transitional step" in the direction of "economic independence that made up a large portion of colonial grievances against parliament, and eventually, King George".[23]

- ^ Ansoff and others believe that this "entirely red" flag was possibly General Israel Putnam's regimental flag as flown on Prospect Hill on 18 July 1775.[28] It features the arms of Connecticut and an abbreviation for the words "Qui Trastulit Susinet" on one side and "An Appeal To Heaven" on the other. DeLear says that from a distance, it might have appeared to be "entirely red" and "functioned as such by both armies". It may have also been just a plain red flag which in ancient Rome served "as a military signal for the Comitia Centuriata to assemble on the Field of Mars" and as the enemy approached, "the flag would be struck as a signal to prepare for battle". There are examples of this practice in the American colonies. A 1768 letter by Governor Francis Bernard mentions the flying of a red flag from a "Liberty-Tree" in connection with a meeting of the Sons of Liberty. There is also a British report during the American Revolution stating "Pearson spied through the morning haze a red flag flying over the old Scarborough Castle on the Yorkshire coastline. The red flag signalled, 'Enemy on our Shores'". Hero of the American Revolution Marquis De Lafayette "raised a red flag at the Champ de Mars (Field of Mars) in 1791 in Paris to indicate a state of martial law". According to DeLear, it was because the red flag was established as a signal for "enemy on our shores" and "as a general signal for emergency, duress, or rebellion" that Putnam's predominantly red regimental flag "would have added import and be entirely appropriate" to be flown on Prospect Hill while the Continental Army was reforming and the rebellious colonists faced the "enemy on our shores" amid the ongoing siege of Boston.[29]

- ^ Prospect Hill was derisively dubbed "Mount Pisgah" by the British as it commanded a view of their defensive lines on the Charlestown Peninsula. As with Moses who ascended the summit so referred to in the Bible, the Americans could also see the inaccessible "promised land" of Charlestown.[1]

- ^ In fact the Continental fleet under the command of Hopkins actually departed from Philadelphia in January 1776.[34]

- ^ DeLear states that "as Ansoff mentions, there is evidence to suggest that this letter was written in December 1775, perhaps as early as 2 December, the day before the Grand Union's unveiling".[46]

- ^ In a letter dated 10 February 1776 the North Carolina Council of Safety mentions the shipment "by the wagon" of "Drums, Colours, Fifes, Pamphlets and a quantity of powder". The colors referred to were purchased by Joseph Hewes from ship chandler James Wharton with the itemised bill stating "1 Union Flag 13 Stripes Broad Buntg and 33 feet fly" and may have been flown in Edenton, North Carolina. The Continental Colours were then featured on a North Carolina seven-and-a-half dollar note dated 2 April 1776.[58] The earliest surviving artwork featuring the Continental Colours is a powderhorn belonging to Major Samuel Selden labelled "SHIP.AMARACA" that seems to bear "a coarse rendering" of the design.[59] There is also a watercolour of Captain Wynkoop's Royal Savage by royal marine lieutenant John Calderwood that dates from the summer of 1776.[60]

- ^ The first time the words "United States of America" appeared in a newspaper was the Virginia Gazette, 6 April 1776 edition.[60]

- ^ DeLear notes that Washington was a well-known Freemason who understood that "strict adherence to ritual and ceremony as not only being a question of virtue, but one of honor".[69] Historian Robert Allison takes issue with Ansoff's revisionism arguing that "Enlistments for the all-volunteer army expired Dec. 31, 1775; Washington was issuing a call to arms for the forces to keep them all from going home". He sees the flying of the Continental Colours as a sign "of differentiation and change in this context". Allison says that "Washington, probably more than any of his contemporaries, knew the importance of symbols". It was "During the siege of Boston, the rebels made the mental transition from angry Brits to independent Americans".[70]

- ^ DeLear cites a description dated 3 March 1776 that the colours of the American fleet "were striped under the Union with 13 strokes, called the Thirteen United Colonies". Also, the readers of London Ladies Magazine, July 1776 edition, were told of a letter, possibly from the same source in New Providence, Bahamas, after the raid by Hopkins, where it is stated, "The colors of the American fleet were striped under the Union, with thirteen strokes called the United Colonies, and their standard, a rattlesnake; motto–Don't Tread on Me!"[77]

- ^ Ansoff notes that despite DeLear stating that his paper would introduce "additional primary and secondary sources" he fails to cite any primary sources for the Prospect Hill raising other than those discussed in Ansoff's original 2006 paper.[80] Ansoff acknowledges there is still more research to be done and claims that his hypothesis is still viable as "DeLear did not fully address the arguments presented in my original paper, and that the evidence he presented fails to support his conclusions and in some cases actually contradicts them".[81]

References

- ^ a b Ansoff 2006, p. 81.

- ^ DeLear 2014, p. 61, note 39.

- ^ Ansoff 2006.

- ^ DeLear 2014.

- ^ DeLear 2018.

- ^ Orchard, Chris (30 December 2013). "Research upholds traditional Prospect Hill flag story". Patch. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- ^ a b Ansoff 2006, p. 77.

- ^ a b c d Ansoff 2006, p. 78.

- ^ DeLear 2018, p. 2.

- ^ Smith 1975, p. 188.

- ^ a b Ansoff 2006, p. 96.

- ^ Ansoff 2006, pp. 78–80.

- ^ Preble 1880, p. 196.

- ^ Preble 1880, p. 197.

- ^ Preble 1880, p. 201.

- ^ Ansoff 2006, p. 96, note 3.

- ^ Ansoff 2006, p. 80.

- ^ a b Ansoff 2006, p. 79.

- ^ a b Ansoff 2006, pp. 79–80.

- ^ a b Ansoff 2006, p. 83.

- ^ a b c d DeLear 2014, p. 37.

- ^ DeLear 2018, p. 63.

- ^ DeLear 2018, p. 76.

- ^ DeLear 2018, p. 13.

- ^ DeLear 2014, pp. 57–58.

- ^ DeLear 2018, p. 3.

- ^ a b c Ansoff 2006, p. 84.

- ^ Ansoff 2006, p. 98, note 16.

- ^ DeLear 2018, p. 42, note 61.

- ^ Ansoff 2006, pp. 84–85.

- ^ a b c d e Ansoff 2006, p. 85.

- ^ Ansoff 2006, pp. 86–87.

- ^ a b c Ansoff 2006, p. 87.

- ^ a b Ansoff 2006, p. 89.

- ^ Ansoff 2006, pp. 88–89.

- ^ Ansoff 2006, pp. 89–90.

- ^ Ansoff 2006, p. 90.

- ^ a b c Ansoff 2006, p. 91.

- ^ Ansoff 2015, pp. 19, 26, note 60.

- ^ Ansoff 2015, p. 19.

- ^ DeLear 2014, p. 19.

- ^ DeLear 2014, p. 35.

- ^ DeLear 2014, pp. 42, 61, note 42.

- ^ DeLear 2014, pp. 42, 62, note 43.

- ^ DeLear 2014, pp. 42, 63, note 44.

- ^ DeLear 2014, p. 62.

- ^ DeLear 2014, pp. 42, 62–63, note 45.

- ^ DeLear 2014, pp. 42, 63, note 46.

- ^ DeLear 2014, pp. 42, 63, note 47.

- ^ DeLear 2014, pp. 42, 63, note 48.

- ^ DeLear 2014, pp. 42, 63, note 49.

- ^ DeLear 2014, p. 36.

- ^ a b Ansoff 2015, p. 11.

- ^ Ansoff 2015, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Ansoff 2015, p. 4.

- ^ Ansoff 2015, pp. 5, 20, note 5.

- ^ a b DeLear 2018, p. 54.

- ^ DeLear 2018, p. 21.

- ^ DeLear 2018, pp. 24–27.

- ^ a b DeLear 2018, p. 22.

- ^ Ansoff 2006, p. 98, note 18.

- ^ DeLear 2018, p. 17.

- ^ DeLear 2018, p. 19.

- ^ DeLear 2018, pp. 54–55.

- ^ DeLear 2018, p. 51.

- ^ DeLear 2018, p. 60.

- ^ DeLear 2018, pp. 50–51.

- ^ a b DeLear 2018, p. 53.

- ^ a b DeLear 2018, p. 52.

- ^ a b Dreilinger, Danielle (31 December 2009). "Unfurling History of Prospect Hill". Boston Globe. Boston.

- ^ DeLear 2018, p. 61.

- ^ Ansoff 2015, pp. 10–11.

- ^ DeLear 2014, pp. 39, 64, note 56.

- ^ a b DeLear 2014, p. 39.

- ^ Richardson 1982, p. 267.

- ^ DeLear 2018, pp. 57–58.

- ^ DeLear 2018, p. 48.

- ^ Ansoff 2015, p. 22, note 19.

- ^ Ansoff 2015, p. 8.

- ^ Ansoff 2015, p. 21.

- ^ Ansoff 2015, p. 1.

Bibliography

Books

- DeLear, Byron (2018). The First American Flag: Revisiting the Grand Union at Prospect Hill. Talbot Publishers. ISBN 978-1-94-683102-6.

- Hamilton, Schuyler (1853). History of the National Flag of the United States of America. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo & Co.

- Preble, George Henry (1880). History of the Flag of the United States of America (second revised ed.). Boston: A. Williams and Co.

- Richardson, Edward W. (1982). Standards and Colors of the American Revolution. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-81-227839-2.

- Smith, Whitney (1975). Flags Through the Ages and Across the World. Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-059093-9.

Journals

- Ansoff, Peter (2006). "The Flag on Prospect Hill". Raven: A Journal of Vexillology. 13: 77–100. doi:10.5840/raven2006134. ISSN 1071-0043.

- Ansoff, Peter (2015). "The Flag on Prospect Hill: A Response to Byron DeLear" (PDF). Raven: A Journal of Vexillology. 22: 1–26. doi:10.5840/raven2015221. ISSN 1071-0043.

- DeLear, Byron (2014). "Revisiting the Flag at Prospect Hill: Grand Union or Just British?" (PDF). Raven: A Journal of Vexillology. 21: 19–70. doi:10.5840/raven2014213.

Newspaper reports

- Dreilinger, Danielle (31 December 2009). "Unfurling History of Prospect Hill". Boston Globe. Boston.

- Orchard, Chris (30 December 2013). "Research upholds traditional Prospect Hill flag story". Patch Media. New York. Retrieved 26 May 2024.

Further reading

- Bell, John (2012). The Siege of Boston. US National Park Service.

- Philbrick, Nathaniel (2013). Bunker Hill: A City, A Siege, A Revolution (1st ed.). New York: Viking Books. ISBN 978-0-67-002544-2.