Mesh generation

Mesh generation is the practice of creating a mesh, a subdivision of a continuous geometric space into discrete geometric and topological cells. Often these cells form a simplicial complex. Usually the cells partition the geometric input domain. Mesh cells are used as discrete local approximations of the larger domain. Meshes are created by computer algorithms, often with human guidance through a GUI, depending on the complexity of the domain and the type of mesh desired. A typical goal is to create a mesh that accurately captures the input domain geometry, with high-quality (well-shaped) cells, and without so many cells as to make subsequent calculations intractable. The mesh should also be fine (have small elements) in areas that are important for the subsequent calculations.

Meshes are used for rendering to a computer screen and for physical simulation such as finite element analysis or computational fluid dynamics. Meshes are composed of simple cells like triangles because, e.g., we know how to perform operations such as finite element calculations (engineering) or ray tracing (computer graphics) on triangles, but we do not know how to perform these operations directly on complicated spaces and shapes such as a roadway bridge. We can simulate the strength of the bridge, or draw it on a computer screen, by performing calculations on each triangle and calculating the interactions between triangles.

A major distinction is between structured and unstructured meshing. In structured meshing the mesh is a regular lattice, such as an array, with implied connectivity between elements. In unstructured meshing, elements may be connected to each other in irregular patterns, and more complicated domains can be captured. This page is primarily about unstructured meshes. While a mesh may be a triangulation, the process of meshing is distinguished from point set triangulation in that meshing includes the freedom to add vertices not present in the input. "Facetting" (triangulating) CAD models for drafting has the same freedom to add vertices, but the goal is to represent the shape accurately using as few triangles as possible and the shape of individual triangles is not important. Computer graphics renderings of textures and realistic lighting conditions use meshes instead.

Many mesh generation software is coupled to a CAD system defining its input, and simulation software for taking its output. The input can vary greatly but common forms are Solid modeling, Geometric modeling, NURBS, B-rep, STL or a point cloud.

Terminology

The terms "mesh generation," "grid generation," "meshing," " and "gridding," are often used interchangeably, although strictly speaking the latter two are broader and encompass mesh improvement: changing the mesh with the goal of increasing the speed or accuracy of the numerical calculations that will be performed over it. In computer graphics rendering, and mathematics, a mesh is sometimes referred to as a tessellation.

Mesh faces (cells, entities) have different names depending on their dimension and the context in which the mesh will be used. In finite elements, the highest-dimensional mesh entities are called "elements," "edges" are 1D and "nodes" are 0D. If the elements are 3D, then the 2D entities are "faces." In computational geometry, the 0D points are called vertices. Tetrahedra are often abbreviated as "tets"; triangles are "tris", quadrilaterals are "quads" and hexahedra (topological cubes) are "hexes."

Techniques

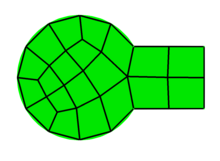

Many meshing techniques are built on the principles of the Delaunay triangulation, together with rules for adding vertices, such as Ruppert's algorithm. A distinguishing feature is that an initial coarse mesh of the entire space is formed, then vertices and triangles are added. In contrast, advancing front algorithms start from the domain boundary, and add elements incrementally filling up the interior. Hybrid techniques do both. A special class of advancing front techniques creates thin boundary layers of elements for fluid flow. In structured mesh generation the entire mesh is a lattice graph, such as a regular grid of squares. In block-structured meshing, the domain is divided into large subregions, each of which is a structured mesh. Some direct methods start with a block-structured mesh and then move the mesh to conform to the input; see Automatic Hex-Mesh Generation based on polycube. Another direct method is to cut the structured cells by the domain boundary; see sculpt based on Marching cubes.

Some types of meshes are much more difficult to create than others. Simplicial meshes tend to be easier than cubical meshes. An important category is generating a hex mesh conforming to a fixed quad surface mesh; a research subarea is studying the existence and generation of meshes of specific small configurations, such as the tetragonal trapezohedron. Because of the difficulty of this problem, the existence of combinatorial hex meshes has been studied apart from the problem of generating good geometric realizations; see Combinatorial Techniques for Hexahedral Mesh Generation. While known algorithms generate simplicial meshes with guaranteed minimum quality, such guarantees are rare for cubical meshes, and many popular implementations generate inverted (inside-out) hexes from some inputs.

Meshes are often created in serial on workstations, even when subsequent calculations over the mesh will be done in parallel on super-computers. This is both because of the limitation that most mesh generators are interactive, and because mesh generation runtime is typically insignificant compared to solver time. However, if the mesh is too large to fit in the memory of a single serial machine, or the mesh must be changed (adapted) during the simulation, meshing is done in parallel.

Algebraic methods

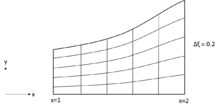

The grid generation by algebraic methods is based on mathematical interpolation function. It is done by using known functions in one, two or three dimensions taking arbitrary shaped regions. The computational domain might not be rectangular, but for the sake of simplicity, the domain is taken to be rectangular. The main advantage of the methods is that they provide explicit control of physical grid shape and spacing. The simplest procedure that may be used to produce boundary fitted computational mesh is the normalization transformation.[1]

For a nozzle, with the describing function the grid can easily be generated using uniform division in y-direction with equally spaced increments in x-direction, which are described by

where denotes the y-coordinate of the nozzle wall. For given values of (, ), the values of (, ) can be easily recovered.

Differential equation methods

Like algebraic methods, differential equation methods are also used to generate grids. The advantage of using the partial differential equations (PDEs) is that the solution of grid generating equations can be exploited to generate the mesh. Grid construction can be done using all three classes of partial differential equations.

Elliptic schemes

Elliptic PDEs generally have very smooth solutions leading to smooth contours. Using its smoothness as an advantage Laplace's equations can preferably be used because the Jacobian found out to be positive as a result of maximum principle for harmonic functions. After extensive work done by Crowley (1962) and Winslow (1966)[2] on PDEs by transforming physical domain into computational plane while mapping using Poisson's equation, Thompson et al. (1974)[3] have worked extensively on elliptic PDEs to generate grids. In Poisson grid generators, the mapping is accomplished by marking the desired grid points on the boundary of the physical domain, with the interior point distribution determined through the solution of equations written below

where, are the co-ordinates in the computational domain, while P and Q are responsible for point spacing within D. Transforming above equations in computational space yields a set of two elliptic PDEs of the form,

where

These systems of equations are solved in the computational plane on uniformly spaced grid which provides us with the co-ordinates of each point in physical space. The advantage of using elliptic PDEs is the solution linked to them is smooth and the resulting grid is smooth. But, specification of P and Q becomes a difficult task thus adding it to its disadvantages. Moreover, the grid has to be computed after each time step which adds up to computational time.[4]

Hyperbolic schemes

This grid generation scheme is generally applicable to problems with open domains consistent with the type of PDE describing the physical problem. The advantage associated with hyperbolic PDEs is that the governing equations need to be solved only once for generating grid. The initial point distribution along with the approximate boundary conditions forms the required input and the solution is the then marched outward. Steger and Sorenson (1980)[5] proposed a volume orthogonality method that uses Hyperbolic PDEs for mesh generation. For a 2-D problem, Considering computational space to be given by , the inverse of the Jacobian is given by,

where represents the area in physical space for a given area in computational space. The second equation links the orthogonality of grid lines at the boundary in physical space which can be written as

For and surfaces to be perpendicular the equation becomes

The problem associated with such system of equations is the specification of . Poor selection of may lead to shock and discontinuous propagation of this information throughout the mesh. While mesh being orthogonal is generated very rapidly which comes out as an advantage with this method.

Parabolic schemes

The solving technique is similar to that of hyperbolic PDEs by advancing the solution away from the initial data surface satisfying the boundary conditions at the end. Nakamura (1982) and Edwards (1985) developed the basic ideas for parabolic grid generation. The idea uses either of Laplace or the Poisson's equation and especially treating the parts which controls elliptic behavior. The initial values are given as the coordinates of the point along the surface and the advancing the solutions to the outer surface of the object satisfying the boundary conditions along edges.

The control of the grid spacing has not been suggested until now. Nakamura and Edwards, grid control was accomplished using non uniform spacing. The parabolic grid generation shows an advantage over the hyperbolic grid generation that, no shocks or discontinuities occur and the grid is relatively smooth. The specifications of initial values and selection of step size to control the grid points is however time-consuming, but these techniques can be effective when familiarity and experience is gained.

Variational methods

This method includes a technique that minimizes grid smoothness, orthogonality and volume variation. This method forms mathematical platform to solve grid generation problems. In this method an alternative grid is generated by a new mesh after each iteration and computing the grid speed using backward difference method. This technique is a powerful one with a disadvantage that effort is required to solve the equations related to grid. Further work needed to be done to minimize the integrals that will reduce the CPU time.

Unstructured grid generation

The main importance of this scheme is that it provides a method that will generate the grid automatically. Using this method, grids are segmented into blocks according to the surface of the element and a structure is provided to ensure appropriate connectivity. To interpret the data flow solver is used. When an unstructured scheme is employed, the main interest is to fulfill the demand of the user and a grid generator is used to accomplish this task. The information storage in structured scheme is cell to cell instead of grid to grid and hence the more memory space is needed. Due to random cell location, the solver efficiency in unstructured is less as compared to the structured scheme.[6]

Some points are needed to be kept in mind at the time of grid construction. The grid point with high resolution creates difficulty for both structured and unstructured. For example, in case of boundary layer, structured scheme produces elongated grid in the direction of flow. On the other hand, unstructured grids require a higher cell density in the boundary layer because the cell needs to be as equilateral as possible to avoid errors.[7]

We must identify what information is required to identify the cell and all the neighbors of the cell in the computational mesh. We can choose to locate the arbitrary points anywhere we want for the unstructured grid. A point insertion scheme is used to insert the points independently and the cell connectivity is determined. This suggests that the point be identified as they are inserted. Logic for establishing new connectivity is determined once the points are inserted. Data that form grid point that identifies grid cell are needed. As each cell is formed it is numbered and the points are sorted. In addition the neighbor cell information is needed.

Adaptive grid

A problem in solving partial differential equations using previous methods is that the grid is constructed and the points are distributed in the physical domain before details of the solution is known. So the grid may or may not be the best for the given problem.[8]

Adaptive methods are used to improve the accuracy of the solutions. The adaptive method is referred to as ‘h’ method if mesh refinement is used, ‘r’ method if the number of grid point is fixed and not redistributed and ‘p’ if the order of solution scheme is increased in finite-element theory. The multi dimensional problems using the equidistribution scheme can be accomplished in several ways. The simplest to understand are the Poisson Grid Generators with control function based on the equidistribution of the weight function with the diffusion set as a multiple of desired cell volume. The equidistribution scheme can also be applied to the unstructured problem. The problem is the connectivity hampers if mesh point movement is very large.

Steady flow and the time-accurate flow calculation can be solved through this adaptive method. The grid is refined and after a predetermined number of iteration in order to adapt it in a steady flow problem. The grid will stop adjusting to the changes once the solution converges. In time accurate case coupling of the partial differential equations of the physical problem and those describing the grid movement is required.

Image-based meshing

Cell topology

Usually the cells are polygonal or polyhedral and form a mesh that partitions the domain. Important classes of two-dimensional elements include triangles (simplices) and quadrilaterals (topological squares). In three-dimensions the most-common cells are tetrahedra (simplices) and hexahedra (topological cubes). Simplicial meshes may be of any dimension and include triangles (2D) and tetrahedra (3D) as important instances. Cubical meshes is the pan-dimensional category that includes quads (2D) and hexes (3D). In 3D, 4-sided pyramids and 3-sided prisms appear in conformal meshes of mixed cell type.

Cell dimension

The mesh is embedded in a geometric space that is typically two or three dimensional, although sometimes the dimension is increased by one by adding the time-dimension. Higher dimensional meshes are used in niche contexts. One-dimensional meshes are useful as well. A significant category is surface meshes, which are 2D meshes embedded in 3D to represent a curved surface.

Duality

Dual graphs have several roles in meshing. One can make a polyhedral Voronoi diagram mesh by dualizing a Delaunay triangulation simplicial mesh. One can create a cubical mesh by generating an arrangement of surfaces and dualizing the intersection graph; see spatial twist continuum. Sometimes both the primal mesh and its dual mesh are used in the same simulation; see Hodge star operator. This arises from physics involving divergence and curl (mathematics) operators, such as flux & vorticity or electricity & magnetism, where one variable naturally lives on the primal faces and its counterpart on the dual faces.

Mesh type by use

Three-dimensional meshes created for finite element analysis need to consist of tetrahedra, pyramids, prisms or hexahedra. Those used for the finite volume method can consist of arbitrary polyhedra. Those used for finite difference methods consist of piecewise structured arrays of hexahedra known as multi-block structured meshes. 4-sided pyramids are useful to conformally connect hexes to tets. 3-sided prisms are used for boundary layers conforming to a tet mesh of the far-interior of the object.

Surface meshes are useful in computer graphics where the surfaces of objects reflect light (also subsurface scattering) and a full 3D mesh is not needed. Surface meshes are also used to model thin objects such as sheet metal in auto manufacturing and building exteriors in architecture. High (e.g., 17) dimensional cubical meshes are common in astrophysics and string theory.

Mathematical definition and variants

What is the precise definition of a mesh? There is not a universally-accepted mathematical description that applies in all contexts. However, some mathematical objects are clearly meshes: a simplicial complex is a mesh composed of simplices. Most polyhedral (e.g. cubical) meshes are conformal, meaning they have the cell structure of a CW complex, a generalization of a simplicial complex. A mesh need not be simplicial because an arbitrary subset of nodes of a cell is not necessarily a cell: e.g., three nodes of a quad does not define a cell. However, two cells intersect at cells: e.g. a quad does not have a node in its interior. The intersection of two cells may be several cells: e.g., two quads may share two edges. An intersection being more than one cell is sometimes forbidden and rarely desired; the goal of some mesh improvement techniques (e.g. pillowing) is to remove these configurations. In some contexts, a distinction is made between a topological mesh and a geometric mesh whose embedding satisfies certain quality criteria.

Important mesh variants that are not CW complexes include non-conformal meshes where cells do not meet strictly face-to-face, but the cells nonetheless partition the domain. An example of this is an octree, where an element face may be partitioned by the faces of adjacent elements. Such meshes are useful for flux-based simulations. In overset grids, there are multiple conformal meshes that overlap geometrically and do not partition the domain; see e.g., Overflow, the OVERset grid FLOW solver. So-called meshless or meshfree methods often make use of some mesh-like discretization of the domain, and have basis functions with overlapping support. Sometimes a local mesh is created near each simulation degree-of-freedom point, and these meshes may overlap and be non-conformal to one another.

Implicit triangulations are based on a delta complex: for each triangle the lengths of its edges, and a gluing map between face edges. (please expand)

High-order elements

Many meshes use linear elements, where the mapping from the abstract to realized element is linear, and mesh edges are straight segments. Higher order polynomial mappings are common, especially quadratic. A primary goal for higher-order elements is to more accurately represent the domain boundary, although they have accuracy benefits in the interior of the mesh as well. One of the motivations for cubical meshes is that linear cubical elements have some of the same numerical advantages as quadratic simplicial elements. In the isogeometric analysis simulation technique, the mesh cells containing the domain boundary use the CAD representation directly instead of a linear or polynomial approximation.

Mesh improvement

Improving a mesh involves changing its discrete connectivity, the continuous geometric position of its cells, or both. For discrete changes, for simplicial elements one swaps edges and inserts/removes nodes. The same kinds of operations are done for cubical (quad/hex) meshes, although there are fewer possible operations and local changes have global consequences. E.g., for a hexahedral mesh, merging two nodes creates cells that are not hexes, but if diagonally-opposite nodes on a quadrilateral are merged and this is propagated into collapsing an entire face-connected column of hexes, then all remaining cells will still be hexes. In adaptive mesh refinement, elements are split (h-refinement) in areas where the function being calculated has a high gradient. Meshes are also coarsened, removing elements for efficiency. The multigrid method does something similar to refinement and coarsening to speed up the numerical solve, but without actually changing the mesh.

For continuous changes, nodes are moved, or the higher-dimensional faces are moved by changing the polynomial order of elements. Moving nodes to improve quality is called "smoothing" or "r-refinement" and increasing the order of elements is called "p-refinement." Nodes are also moved in simulations where the shape of objects change over time. This degrades the shape of the elements. If the object deforms enough, the entire object is remeshed and the current solution mapped from the old mesh to the new mesh.

Research community

Practitioners

The field is highly interdisciplinary, with contributions found in mathematics, computer science, and engineering. Meshing R&D is distinguished by an equal focus on discrete and continuous math and computation, as with computational geometry, but in contrast to graph theory (discrete) and numerical analysis (continuous). Mesh generation is deceptively difficult: it is easy for humans to see how to create a mesh of a given object, but difficult to program a computer to make good decisions for arbitrary input a priori. There is an infinite variety of geometry found in nature and man-made objects. Many mesh generation researchers were first users of meshes. Mesh generation continues to receive widespread attention, support and funding because the human-time to create a mesh dwarfs the time to set up and solve the calculation once the mesh is finished. This has always been the situation since numerical simulation and computer graphics were invented, because as computer hardware and simple equation-solving software have improved, people have been drawn to larger and more complex geometric models in a drive for greater fidelity, scientific insight, and artistic expression.

Journals

Meshing research is published in a broad range of journals. This is in keeping with the interdisciplinary nature of the research required to make progress, and also the wide variety of applications that make use of meshes. About 150 meshing publications appear each year across 20 journals, with at most 20 publications appearing in any one journal. There is no journal whose primary topic is meshing. The journals that publish at least 10 meshing papers per year are in bold.

- Advances in Engineering Software

- American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics Journal (AIAAJ)

- Algorithmica

- Applied Computational Electromagnetics Society Journal

- Applied Numerical Mathematics

- Astronomy and Computing

- Computational Geometry: Theory and Applications

- Computer-Aided Design, often including a special issue devoted to extended papers from the IMR (see conferences below)

- Computer Aided Geometric Design (CAGD)

- Computer Graphics Forum (Eurographics)

- Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering

- Discrete and Computational Geometry

- Engineering with Computers

- Finite Elements in Analysis and Design

- International Journal for Numerical Methods in Engineering (IJNME)

- International Journal for Numerical Methods in Fluids

- International Journal for Numerical Methods in Biomedical Engineering

- International Journal of Computational Geometry & Applications

- Journal of Computational Physics (JCP)

- Journal on Numerical Analysis

- Journal on Scientific Computing (SISC)

- Transactions on Graphics (ACM TOG)

- Transactions on Mathematical Software (ACM TOMS)

- Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics (IEEE TVCG)

- Lecture Notes in Computational Science and Engineering (LNCSE)

- Computational Mathematics and Mathematical Physics (CMMP)

Conferences

(Conferences whose primary topic is meshing are in bold.)

- Aerospace Sciences Meeting AIAA (15 meshing talks/papers)

- Canadian Conference on Computational Geometry CCCG

- CompIMAGE: International Symposium Computational Modeling of Objects Represented in Images

- Computational Fluid Dynamics Conference AIAA

- Computational Fluid Dynamics Conference ECCOMAS

- Computational Science & Engineering CS&E

- Conference on Numerical Grid Generation ISGG

- Eurographics Annual Conference (Eurographics)] (proceedings in Computer Graphics Forum)

- Geometric & Physical Modeling SIAM

- International Conference on Isogeometric Analysis IGA

- International Symposium on Computational Geometry SoCG

- Numerical Geometry, Grid Generation and Scientific Computing (NUMGRID) (proceedings in Lecture Notes in Computational Science and Engineering)

- International Meshing Roundtable, SIAM IMR workshop. (Refereed proceedings and special journal issue.)

- SIGGRAPH (proceedings in ACM Transactions on Graphics)

- Symposium on Geometry Processing SGP (Eurographics) (proceedings in Computer Graphics Forum)

- World Congress on Engineering

Workshops

Workshops whose primary topic is meshing are in bold.

- Conference on Geometry: Theory and Applications CGTA

- European Workshop on Computational Geometry EuroCG

- Fall Workshop on Computational Geometry

- Finite Elements in Fluids FEF

- MeshTrends Symposium (in WCCM or USNCCM alternate years)

- Polytopal Element Methods in Mathematics and Engineering

- Tetrahedron workshop

See also

- Delaunay triangulation – Triangulation method

- Fortune's algorithm – Voronoi diagram generation algorithm

- Grid classification

- Mesh parameterization

- Meshfree methods

- Parallel mesh generation

- Principles of grid generation

- Polygon mesh

- Regular grid

- Ruppert's algorithm – Algorithms for mesh generation

- Stretched grid method

- Tessellation (computer graphics)

- Types of mesh

- Unstructured grid

References

- ^ Anderson, Dale (2012). Computational Fluid Mechanics and Heat Transfer, Third Edition Series in Computational and Physical Processes in Mechanics and Thermal Sciences. CRC Press. pp. 679–712. ISBN 978-1591690375.

- ^ Winslow, A (1966). "Numerical Solution of Quasi-linear Poisson Equation". J. Comput. Phys. 1 (2): 149–172. doi:10.1016/0021-9991(66)90001-5.

- ^ Thompson, J.F.; Thames, F.C.; Mastin, C.W. (1974). "Automatic Numerical Generation of Body-fitted Curvilinear Coordinate System for Field Containing any Number of Arbitrary Two-Dimensional Bodies". J. Comput. Phys. 15 (3): 299–319. Bibcode:1974JCoPh..15..299T. doi:10.1016/0021-9991(74)90114-4.

- ^ Young, David (1954). "Iterative methods for solving partial difference equations of elliptic type". Transactions of the American Mathematical Society. 76 (1): 92–111. doi:10.2307/1990745. ISSN 1088-6850. JSTOR 1990745.

- ^ Steger, J.L; Sorenson, R.L (1980). "Use of hyperbolic partial differential equation to generate body fitted coordinates, Numerical Grid Generation Techniques" (PDF). NASA Conference Publication 2166: 463–478.

- ^ Venkatakrishnan, V; Mavriplis, D. J (May 1991). "Implicit solvers for unstructured meshes". Journal of Computational Physics. 105 (1): 23. doi:10.1006/jcph.1993.1055. hdl:2060/19910014812. S2CID 123202432.

- ^ Weatherill, N.P (September 1992). "Delaunay triangulation in computational fluid dynamics". Computers & Mathematics with Applications. 24 (5–6): 129–150. doi:10.1016/0898-1221(92)90045-j.

- ^ Anderson, D.A; Sharpe H.N. (July 1993). "Orthogonal Adaptive Grid Generation with Fixed Internal Boundaries for Oil Reservoir Simulation". SPE Advanced Technology Series. 2. 1 (2): 53–62. doi:10.2118/21235-PA.

Bibliography

- Edelsbrunner, Herbert (2001), "Geometry and Topology for Mesh Generation", Applied Mechanics Reviews, 55 (1), Cambridge University Press: B1 – B2, Bibcode:2002ApMRv..55B...1E, doi:10.1115/1.1445302, ISBN 978-0-521-79309-4.

- Frey, Pascal Jean; George, Paul-Louis (2000), Mesh Generation: Application to Finite Elements, Hermes Science, ISBN 978-1-903398-00-5.

- P. Smith and S. S. Sritharan (1988), "Theory of Harmonic Grid Generation" (PDF), Complex Variables, 10 (4): 359–369, doi:10.1080/17476938808814314

- S. S. Sritharan (1992), "Theory of Harmonic Grid Generation-II", Applicable Analysis, 44 (1): 127–149, doi:10.1080/00036819208840072

- Thompson, J. F.; Warsi, Z. U. A.; Mastin, C. W. (1985), Numerical Grid Generation: Foundations and Applications, North-Holland, Elsevier.

- CGAL The Computational Geometry Algorithms Library

- Oden, J.Tinsley; Cho, J.R. (1996), "Adaptive hpq-Finite Element Methods of Hierarchical Models for Plate- and Shell-like Structures", Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering, 136 (3): 317–345, Bibcode:1996CMAME.136..317O, doi:10.1016/0045-7825(95)00986-8

- Steven J. Owen (1998), A Survey of Unstructured Mesh Generation Technology, International Meshing Roundtable, pp. 239–267, S2CID 2675840

- Shimada, Kenji; Gossard, David C. (1995). Bubble Mesh: Automated Triangular Meshing of Non-Manifold Geometry by Sphere Packing. ACM Symposium on Solid Modeling and Applications, SMA. ACM. pp. 409-419. doi:10.1145/218013.218095. ISBN 0-89791-672-7. S2CID 1282987.

- Jan Brandts, Sergey Korotov, Michal Krizek: "Simplicial Partitions with Applications to the Finite Element Method", Springer Monographs in Mathematics,ISBN 978-3030556761 (2020). url="https://www.springer.com/gp/book/9783030556761"

- Grid Generation Methods - Liseikin, Vladimir D.

External links

- Periodic Table of the Finite Elements

- Literature on Mesh Generation

- Conferences, Workshops, Summerschools

- Mesh generators

Many commercial product descriptions emphasize simulation rather than the meshing technology that enables simulation.

- Lists of mesh generators (external):

- ANSA Pre-processor

- ANSYS

- CD-adapco and Siemens DISW

- Comet Solutions

- CGAL Computational Geometry Algorithms Library

- CUBIT

- Ennova

- Gmsh

- Hextreme meshes

- MeshLab

- MSC Software

- Omega_h Tri/Tet Adaptivity

- Open FOAM Mesh generation and conversion

- Salome Mesh module

- TetGen

- TetWild

- TRIANGLE Mesh generation and Delaunay triangulation

- Multi-domain partitioned mesh generators

These tools generate the partitioned meshes required for multi-material finite element modelling.

- MDM(Multiple Domain Meshing) generates unstructured tetrahedral and hexahedral meshes for a composite domain made up of heterogeneous materials, automatically and efficiently

- QMDM (Quality Multi-Domain Meshing) produces a high quality, mutually consistent triangular surface meshes for multiple domains

- QMDMNG, (Quality Multi-Domain Meshing with No Gap), produces a quality meshes with each one a two-dimensional manifold and no gap between two adjacent meshes.

- SOFA_mesh_partitioning_tools generates partitioned tetrahedral meshes for multi-material FEM, based on CGAL.

- Articles

- Another Fine Mesh, MeshTrends Blog, Pointwise

- Mesh Generation & Grid Generation on the Web

- Mesh Generation group on LinkedIn

- Research groups and people

- Mesh Generation people on Google Scholar

- David Bommes, Computer Graphics Group, University of Bern

- David Eppstein's Geometry in Action, Mesh Generation

- Jonathan Shewchuk's Meshing and Triangulation in Graphics, Engineering, and Modeling

- Scott A. Mitchell

- Robert Schneiders

- Models and meshes

Useful models (inputs) and meshes (outputs) for comparing meshing algorithms and meshes.

- HexaLab has models and meshes that have been published in research papers, reconstructed or from the original paper.

- Princeton Shape Benchmark Archived 2021-07-03 at the Wayback Machine

- Shape Retrieval Contest SHREC has different models each year, e.g.,

- Thingi10k meshed models from the Thingiverse

- CAD models

Modeling engines linked with mesh generation software to represent the domain geometry.

- Mesh file formats

Common (output) file formats for describing meshes.

- NetCDF

- Genesis/Exodus

- XDMF

- VTK/VTU

- MEDIT

- MED/Salome

- Gmsh

- ANSYS mesh

- OFF

- Wavefront OBJ

- PLY

- STL

- meshio can convert between all of the above formats.

- Mesh visualizers

- Tutorials