Elisabeth of Romania

| Elisabeth of Romania | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Queen consort of the Hellenes | |||||

| Tenure | 27 September 1922 – 25 March 1924 | ||||

| Born | 12 October 1894 Peleş Castle, Sinaia, Kingdom of Romania | ||||

| Died | 14 November 1956 (aged 62) Villa Rose Alba, Cannes, France | ||||

| Burial | Hedinger Church, Sigmaringen, Baden-Württemberg, Germany | ||||

| Spouse | |||||

| |||||

| House | Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen | ||||

| Father | Ferdinand I of Romania | ||||

| Mother | Marie of Edinburgh | ||||

Elisabeth of Romania (Elisabeth Charlotte Josephine Alexandra Victoria) Romanian: Elisabeta, Greek: Ελισάβετ; 12 October 1894 – 14 November 1956) was the second child and eldest daughter of King Ferdinand I and Queen Marie of Romania. She was Queen of the Hellenes from 27 September 1922 until 25 March 1924 as the wife of King George II.

Elisabeth was born when her parents were crown prince and crown princess of Romania. She was raised by her great-uncle and great-aunt, King Carol I and Queen Elisabeth. Princess Elisabeth was an introvert and socially isolated. She became crown princess of Greece when she married George in 1921, but she felt no passion for him and underwent the political turmoil in her adopted country after World War I. When her husband succeeded to the Greek throne in 1922, Elisabeth was involved in assisting refugees who arrived to Athens after the disaster of the Greco-Turkish War. The rise of the revolutionary climate, however, affected her health and with great relief she left the Kingdom of Greece with her husband in December 1923. The royal couple then settled in Bucharest, and George was deposed on 25 March 1924, upon the abolition of the Greek monarchy.

In Romania, Elisabeth and George's relationship deteriorated, and they divorced in 1935. Very close to her brother Carol II of Romania, the former queen amassed an important fortune, partly due to financial advice given by her lover, the banker Alexandru Scanavi. After the death of her mother in 1938 and the abdication of King Carol II in 1940, Elisabeth took up the role of First Lady of Romania. At the end of World War II, she established close links with the Romanian Communist Party and openly conspired against her nephew, the young King Michael I, earning the nickname of "Red Aunt" of the sovereign. However, her communist links did not prevent her from being expelled from the country when the Romanian People's Republic was proclaimed in 1947. Elisabeth moved to Switzerland and then to Cannes, in southern France. She had a romantic relationship with Marc Favrat, a would-be artist almost thirty years younger, whom she finally adopted just before her death in 1956.[1]

Early years

Second child and first daughter of Crown Prince Ferdinand and Crown Princess Marie of Romania, Elisabeth (nicknamed Lisabetha or Lizzy by her family) was born on 12 October 1894 at Peleş Castle, Sinaia.[2] Named after her paternal great-aunt, Queen Elisabeth of Wied,[3] shortly after birth she was removed from her parents, as King Carol I and Queen Elizabeth thought Crown Prince Ferdinand and Crown Princess Marie were too young, liberate and inexperienced to give their own children a real, proper, royal upbringing. With her older brother Prince Carol, she was raised by King Carol I and his wife.[4][5] In her memoirs, Marie described her eldest daughter as "a lovely solemn-faced child who had a strong sense of rectitude." Over the years, Elisabeth developed a cold character and a volatile temperament which socially isolated her. Considered "vulgar" by her mother, she was, however, considered a classic beauty.[2]

Marriage

An undesired engagement

In 1911, Prince George of Greece, then second-in-line to the throne and his future wife's second cousin, met Elisabeth for the first time.[6] After the Balkan Wars, during which Greece and Romania were allied, the Greek prince asked for the hand of Elisabeth, but, advised by her great-aunt, she declined the offer, saying that her suitor was too small and too English in his manners. Disdainful, the princess even said on the occasion, that "God began the prince but forgot to finish him" (1914).[7][8]

During World War I, Elisabeth was involved in helping wounded soldiers. She made daily visits to the hospitals and distributed cigarettes and comforting words to the victims of the fighting.[9]

In 1919, Elisabeth and her sisters Maria and Ileana accompanied their mother, now Queen Marie, to Paris at the Peace Conference. The sovereign hoped that during her stay there she could find suitable husbands for her daughters, especially Elisabeth, already aged twenty-five.[10] After a few months in France, the Queen and her daughters decided to return to Romania in early 1920. On the way back, they made a brief stop in Switzerland, where they found the Greek royal family, who lived in exile since the deposition of King Constantine I during the Great War. Elisabeth then met again Prince George (now Diadochos and heir of the throne), who asked again her hand. Now more aware of her own imperfections (her mother described her as fat and of very limited intelligence), Elisabeth decided to accept the marriage. However, at that time the future of the Diadochos was far from certain: displaced from the throne with his father and replaced by his younger brother, now King Alexander I, George was forbidden to stay in his country, penniless and without any prospects.[6][11]

Nevertheless, the engagement satisfied both Elisabeth and George's parents. Delighted to have finally found a husband for her eldest daughter, the Queen of Romania soon invited the prince to travel to Bucharest in order to publicly announce the engagement.[11] George agreed but soon after his arrival in the country of his fiancée, he learned of the accidental death of Alexander I and the ensuing political turmoil that erupted in Greece.[12][13]

Life in Greece

Restoration of the Greek royal family. Wedding of George and Elisabeth

On 5 December 1920 a referendum of disputed results[a] called the Greek royal family to return home.[14] King Constantine I, Queen Sophia and Diadochos George therefore returned to Athens on 19 December. Their return was accompanied by a significant jubilation. A huge crowd surrounded the sovereign and the heir to the throne through the streets of the capital. Once at the palace, they appeared repeatedly on the balcony to greet the people who cheered them.[15][16]

Wedding

However, a few weeks later George returned to Romania to marry Elisabeth. The wedding took place with great pomp in Bucharest on 27 February 1921.[17] Shortly after on March 10, Crown Prince Carol of Romania, Elisabeth's elder brother, married George's younger sister, Princess Helen of Greece.[2][12]>[18]

Crown princess

In Greece, Elisabeth had great difficulty integrating into the royal family, and her relationship with Queen Sophia was particularly awkward.[2][19] From an introverted temperament that could be mistaken as arrogance,[20][21] Elisabeth felt displaced by her in-laws, who regularly spoke in Greek in her presence, because she had not yet mastered the language.[2][22] Only King Constantine I and his sister, the Grand Duchess Maria Georgievna of Russia, found favor in her eyes.[2][21] Indeed, even the shy Diadochos disappointed his wife, who wanted to share with him a more passionate relationship.[23][24]

Regretting not having her own home and being forced to constantly live with her in-laws, Elisabeth spent the already little revenues of her husband into redecorating their apartments. In addition, her family delayed in paying her dowry[23] and the savings that she left in Romania were soon lost because of the poor investments made by the manager of her fortune.[25]

Facing a very difficult political situation, due to the Greco-Turkish War, Elisabeth quickly understood that her space to maneuver was limited in her new country. However, she integrated the Red Cross, which was overwhelmed by the arrival of wounded coming from Anatolia.[21][26] The Crown Princess also occupied her free time practicing gardening, painting and drawing. She illustrated a book of poems written by the Belgian author Emile Verhaeren. She also liked writing and producing some new books of low value.[23][27] Finally, she spent long hours studying the Modern Greek, a language that was extremely hard for her to learn.[25]

Disappointed by the mediocrity of her daily routine, Elisabeth began to nourish jealousy for her sister Maria, married to King Alexander I of Yugoslavia, and her sister-in-law Helen of Greece, wife of her brother Crown Prince Carol of Romania.[23][28] With the war and the revolution, the everyday life of the Greek royal family was indeed increasingly difficult, and the pension received by the Diadochos George didn't allow her to buy the clothes and jewelry that she wanted.[23]

Already strained by the war, the relations of the Diadochos and his wife were clouded by their inability to give an heir to the Kingdom of Greece. Elisabeth became pregnant a few months after her marriage, but she suffered a miscarriage during an official trip to Smyrna.[b] Deeply affected by her miscarriage, the crown princess became sick with typhoid soon followed by pleurisy and worsened by depression. She found refuge with her family in Bucharest, but despite the efforts of her mother and husband, neither Elisabeth's health nor her marriage fully recovered from the loss of her child.[31][32][33]

Queen of the Hellenes

Meanwhile, the disaster of the Greco-Turkish War forced King Constantine I to abdicate, which pushed George on to the throne (27 September 1922).[32] The new king, however, had no power, and he and his queen were unable to resolve the repression organized by revolutionaries who took power against the representatives of the old regime. The new royal couple saw with anguish the near execution of Prince Andrew (the king's uncle) at the Trial of the Six.[34][35]

Despite this difficult context, Elisabeth tried to make herself useful to her adopted country. To respond to the influx of refugees originating from Anatolia, the Queen had built shacks on the outskirts of Athens. To carry out her projects, she mobilized her family and asked her mother, Queen Marie, to send wood and other materials.[34][36]

However, Elisabeth found it increasingly difficult to cope with Greece and its revolutionary climate. Her love for George II was over, and her letters to her mother show how much she worried for her future.[36][37] Her correspondence also revealed that she had no desire to have children.[38]

After an attempted monarchist coup d'état in October 1923, the situation of the royal couple became even more precarious. On 19 December 1923 King George II and his wife were forced into exile by the revolutionary government. With Prince Paul (the king's brother and heir-presumptive to the throne), they then departed for Romania, where they learned of the proclamation of the Second Hellenic Republic on 25 March 1924.[39][40][41]

Return to Romania

Queen in exile

In Romania, George II and Elizabeth moved to Bucharest, where King Ferdinand I and Queen Marie gave to them a wing of Cotroceni Palace. After a few weeks, the couple moved to a modest villa in the Calea Victoriei. Regular guests of the Romanian sovereigns, the exiled Greek royal couple participated in court ceremonies. But despite the kindness shown by his mother-in-law, the exiled King of Greece in Bucharest felt aimless and barely concealed the boredom that he felt at the Romanian court.[39][42][43]

Unlike her husband, Elisabeth was delighted with her return to Romania. Her relationship with her mother was sometimes stormy, even if their literary collaborations were successful. In the mid 1920s, Elisabeth illustrated the latest work of her mother, The Country That I Love (1925).[c][44] The links with Crown Princess Helen of Romania (wife of Crown Prince Carol of Romania and sister of King George II of Greece) remained complicated due to the jealousy that the exiled Queen of the Hellenes still continued to feel against her sister-in-law.[45]

Exacerbated by the humiliations of exile, financial difficulties and the lack of offspring, the relations between George II and Elisabeth deteriorated. After initially alleviating her weariness with too much rich food and gambling, the former Queen of the Hellenes began a series of extramarital relationships with several married men. She even flirted with her brother-in-law King Alexander I of Yugoslavia when she visited her sister Queen Maria during an illness in Belgrade. Later, she entered into an affair with the banker of her husband, a Greek-Romanian named Alexandru Scanavi, who was appointed her chamberlain to cover up the scandal. However, Elisabeth was not the only one responsible for the failure of her marriage: over the years, George II spent less time with his wife and gradually settled his residence in the United Kingdom, where he also entered into an adulterous relationship.[46][47][48][49]

In May 1935, Elisabeth heard from a Greek diplomat that the Second Hellenic Republic was on the verge of collapse and that the restoration of the monarchy was imminent.[49] Frightened by this news, the exiled Queen of the Hellenes then launched divorce proceedings without informing her husband. Charged with "desertion from the family home", George II saw his marriage dissolved by a Bucharest court without being really invited to speak on the matter (6 July 1935).[39][48][49][50][51]

An ambitious princess

After the death of King Ferdinand I in 1927, Romania began a period of great instability. After Crown Prince Carol renounced his rights to be able to live with his mistress Magda Lupescu, his son ascended to the throne as King Michael I under the direction of a Council of Regency.[52] Nevertheless, a significant part of the population supported the rights of Carol,[53] who finally managed to take the crown in 1930.[54] Very close to her brother, Elisabeth actively supported his return to Romania. She kept him daily informed of the country's political life during his years of exile.[55]

Once on the throne, Carol II maintained stormy relations with the members of his family but retained his confidence in Elisabeth, who was the only member of the royal family who accepted his mistress.[56] Thanks to the inheritance received from her father,[57] the financial advice of her lover, the banker Alexandru Scanavi, and her good relations with her brother, the princess managed to live in great style in Romania.[58][59] In March 1935, she acquired the large domain of Banloc, near the border with Yugoslavia, a mansion in Sinaia and an elegant villa of Italian style, called Elisabeta Palace, located in the Șoseaua Kiseleff in Bucharest.[58]

After the death of the Queen Mother Marie in 1938 and the deposition of Carol II in 1940, Elisabeth played the role of First Lady of Romania. Ambitiously, the princess had indeed no remorse to follow her brother's policy, even when she showed herself tyrannical with other members of the royal family.[60] After the return to the throne of Michael I and the establishment of the dictatorship of Marshal Ion Antonescu, Elisabeth stayed out of politics.[61] However, from 1944, she forged links with the Romanian Communist Party and openly conspired against her nephew, who now considered her a spy.[60][62][63] In early 1947, she received in her domain of Banloc the Marshal Tito, who deposed another of her nephews, the young King Peter II of Yugoslavia.[64][65] Finally, through Alexandru Scanavi, the Princess participated in the financing of the guerrilla who fought against her former brother-in-law, the now King Paul I, in Greece.[60]

However, Elisabeth wasn't the only member of the Romanian royal family who had friendly relations with the communists: her sister Ileana did the same in the hope of putting her eldest son, Archduke Stefan of Austria, on the throne. For these reasons, the two princesses then received the nickname of "Red Aunts" of King Michael I.[66]

Last years

Despite her links with the Romanian Communist Party, Elisabeth was forced to leave the country after the proclamation of the Romanian People's Republic, on 30 December 1947. The new regime gave her three days to pack her belongings and the Elisabeta Palace was ransacked. However, before she went into exile, the princess had time to burn her archives in the domain of Banloc.[60] On 12 January 1948 she left Romania with her sister Ileana aboard a special train provided by the Communists. The Scanavi family accompanied them, but both princesses lost much of their property after being expelled from the country.[67]

Elisabeth settled firstly in Zürich and then in Cannes, at the Villa Rose Alba. In France, she met a handsome young seducer and would-be artist named Marc Favrat.[citation needed] Having fallen in love with the young man, the princess wished to marry him and asked her cousin, Frederick, Prince of Hohenzollern, to bestow a title on him, but Frederick refused.[1] The princess then decided to adopt her lover; which she did three months before her death. She died at her home on 14 November 1956.[68][69]

The body of the princess was transferred to the Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen crypt, the Hedinger Kirche of Sigmaringen.[citation needed]

Archives

Young Princess Elisabeth's letters to her grandfather, Leopold of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, are preserved in the Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen family archive, which is in the State Archive of Sigmaringen (Staatsarchiv Sigmaringen) in the town of Sigmaringen, Baden-Württemberg, Germany.[70]

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Elisabeth of Romania |

|---|

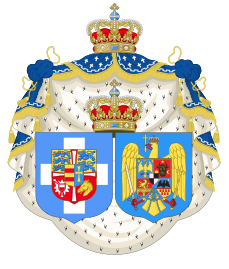

Arms and monogram

- Royal Monogram as Princess Elisabeth of Romania

- Coat of Arms of Queen Elisabeth of Greece

- Royal Monogram of Queen Elisabeth of Greece

Notes

- ^ 99% of voters would cast in favor of the deposed sovereign.[14]

- ^ In his biography of Elisabeth, John Wimbles doesn't mention this pregnancy and the miscarriage that followed. Other authors, like Michael Darlow, have a very different theory of this event. According to them, the Crown Princess became pregnant after an affair with the British diplomat Frank Rattigan, and the miscarriage was merely a disguised abortion to prevent the birth of an illegitimate child.[29][30]

- ^ See the illustrations in: The Country That I Love by Marie Queen of Rumania [retrieved 20 July 2016].

References

- ^ a b Smith, Connell (5 December 2017). "How this painting by a 'toy boy' to a Romanian princess ended up in a Saint John auction". CBC News. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f Mateos Sáinz de Medrano 2004, p. 183.

- ^ Marcou 2002, p. 42.

- ^ Gelardi 2006, p. 76.

- ^ Marcou 2002, p. 43.

- ^ a b Marcou 2002, p. 122.

- ^ Queen Marie of Romania 2006, p. 61.

- ^ Van der Kiste 1994, p. 121.

- ^ Wimbles 2002, p. 137 and 140.

- ^ Marcou 2002, p. 112.

- ^ a b Van der Kiste 1994, p. 122.

- ^ a b Van der Kiste 1994, p. 130.

- ^ Marcou 2002, pp. 117–118.

- ^ a b Van der Kiste 1994, p. 126.

- ^ Van der Kiste 1994, pp. 128–129.

- ^ Gelardi 2006, pp. 295–296.

- ^ "Wedding Of Princess Elizabeth Of Romania To The Crown Prince Of Greece 1921". British Pathe News. Retrieved 27 September 2021.

- ^ Palmer and Greece 1990, p. 63.

- ^ Wimbles 2002, p. 136, 138 and 141.

- ^ Gelardi 2006, p. 309.

- ^ a b c Wimbles 2002, p. 137.

- ^ Wimbles 2002, p. 136.

- ^ a b c d e Mateos Sáinz de Medrano 2004, p. 185.

- ^ Wimbles 2002, p. 137–138.

- ^ a b Wimbles 2002, p. 138.

- ^ Mateos Sáinz de Medrano| 2004, p. 184.

- ^ Wimbles 2002, p. 139.

- ^ Wimbles 2002, p. 140 and 141–142.

- ^ Michael Darlow, Terence Rattigan: The Man and his Work, Quartet Books 2010, p. 51.

- ^ Geoffrey Wansell, Terence Rattigan (London: Fourth Estate, 1995) ISBN 978-1-85702-201-8

- ^ Palmer and Greece 1990, p. 65.

- ^ a b Mateos Sáinz de Medrano 2004, pp. 185–186.

- ^ Van der Kiste 1994, p. 138.

- ^ a b Mateos Sáinz de Medrano 2004, p. 186.

- ^ Wimbles 2002, p. 168.

- ^ a b Wimbles 2002, p. 169

- ^ Mateos Sáinz de Medrano 2004, pp. 186–187.

- ^ Wimbles 2002, p. 171.

- ^ a b c Mateos Sáinz de Medrano 2004, p. 187.

- ^ Van der Kiste 1994, p. 144.

- ^ Wimbles 2002, pp. 173–174.

- ^ Van der Kiste 1994, pp. 145, 148.

- ^ Gelardi 2006, p. 310.

- ^ Wimbles 2003, p. 200.

- ^ Wimbles 2003, p. 203.

- ^ Mateos Sáinz de Medrano 2004, pp. 187–188.

- ^ Van der Kiste 1994, p. 145.

- ^ a b Vickers 2000, p. 263

- ^ a b c Wimbles 2003, p. 204.

- ^ Palmer and Greece 1990, p. 70.

- ^ Van der Kiste 1994, p. 151.

- ^ Marcou 2002, pp. 144–146.

- ^ Marcou 2002, pp. 156–164.

- ^ Marcou 2002, p. 197.

- ^ Marcou 2002, pp. 164, 172, 197.

- ^ Marcou 2002, pp. 222–223.

- ^ Wimbles 2003, p. 202.

- ^ a b Mateos Sáinz de Medrano 2004, p. 191.

- ^ Gelardi 2006, pp. 361–362.

- ^ a b c d Mateos Sáinz de Medrano 2004, p. 192.

- ^ Wimbles 2003, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Wimbles 2003, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Porter 2005, p. 152 and 155.

- ^ Wimbles 2003, p. 15.

- ^ Porter 2005, pp. 169–170.

- ^ Besse 2010, pp. 117–118.

- ^ Mateos Sáinz de Medrano 2004, pp. 192–193.

- ^ Mateos Sáinz de Medrano 2004, p. 193.

- ^ Wimbles 2003, p. 16.

- ^ "Briefe von Prinz Carol und Prinzessin Elisabeta von Rumänien an Fürst Leopold von Hohenzollern". Staatsarchiv Sigmaringen. Retrieved 1 October 2021.

Bibliography

- Mateos Sáinz de Medrano, Ricardo (2004). La familia de la reina Sofía : la dinastía griega, la Casa de Hannover y los reales primos de Europa (1. ed.). Madrid: La Esfera de los Libros. ISBN 84-9734-195-3. OCLC 55595158.

- Gelardi, Julia P. (2006). Born to rule : granddaughters of Victoria, queens of Europe : Maud of Norway, Sophie of Greece, Alexandra of Russia, Marie of Romania, Victoria Eugenie of Spain. London: Review. ISBN 0-7553-1392-5.

- Marcou, Lilly (2002). Le roi trahi : Carol II de Roumanie. Paris: Pygmalion/G. Watelet. ISBN 2-85704-743-6. OCLC 49567918.

- Queen Marie of Romania, Însemnari zilnice, vol. 3, Editura Historia, 2006

- Van der Kiste, John (1994). Kings of the Hellenes: The Greek Kings, 1863–1974. Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0-7509-2147-1.

- Hannah Pakula, The Last Romantic: A Biography of Queen Marie of Roumania, Weidenfeld & Nicolson History, 1996 ISBN 1-85799-816-2

- Prince of Greece, Michel; Palmer, Alan (1990). The Royal House of Greece. London: Weidenfeld Nicolson Illustrated. ISBN 0-297-83060-0. OCLC 59773890.

- John Wimbles, Elisabeta of the Hellenes: Passionate Woman, Reluctant Queen - Part 1: Crown Princess, Royalty Digest, vol. 12#5, no 137, November 2002, pp. 136–144 ISSN 0967-5744

- John Wimbles, Elisabeta of the Hellenes: Passionate Woman, Reluctant Queen - Part. 2: Crown Princess, Royalty Digest, vol. 12#6, no 138, December 2002, pp. 168–174 ISSN 0967-5744

- John Wimbles, Elisabeta of the Hellenes: Passionate Woman, Reluctant Queen - Part. 3: Exile at Home 1924–1940, Royalty Digest, vol. 12#7, no 139, January 2003, pp. 200–205 ISSN 0967-5744

- John Wimbles, Elisabeta of the Hellenes: Passionate Woman, Reluctant Queen - Part. 4: Treachery and Death , Royalty Digest, vol. 13#1, no 145, July 2003, pp. 13–16 ISSN 0967-5744

- Ivor Porter, Michael of Romania: The King and the Country, Sutton Publishing Ltd, 2005 ISBN 0-7509-3847-1

- Jean-Paul Besse, Ileana: l'archiduchesse voilée, Versailles, Via Romana, 2010 ISBN 978-2-916727-74-5

- The Romanovs: The Final Chapter (Random House, 1995) by Robert K. Massie, pgs 210–212, 213, 217, and 218ISBN 0-394-58048-6 and ISBN 0-679-43572-7

- Ileana, Princess of Romania. I Live Again. New York: Rinehart, 1952. First edition.

- Lillian Hellman: A Life with Foxes and Scoundrels (2005), by Deborah Martinson, PhD. (Associate Professor and Chair of English Writing at Occidental College)

External links

- Elisabeta de România, prinţesa capricioasă care s-a retras la conacul din Banloc, article by Ștefan Both in Adevărul, 2013

- Ileana of Romania Is Dead at 82; Princess Founded Convent in U.S., article by Eric Pace in The New York Times, 1991