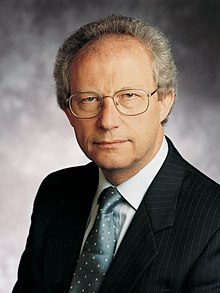

Premiership of Henry McLeish

| |

| Premiership of Henry McLeish 26 October 2000 – 8 November 2001 | |

| Monarch | Elizabeth II |

|---|---|

| Cabinet | McLeish government |

| Party | Labour Party in Scotland |

| Seat | Bute House |

|

| |

Henry McLeish's term as first minister of Scotland began on 26 October 2000 when he was formally sworn into office at the Court of Session. It followed the death of Donald Dewar. McLeish served as the second First Minister, and his premiership is the shortest of any officeholder. His term was dominated by his financial scandal, known as Officegate. The scandal resulted in McLeish's resignation on 8 November 2001.

McLeish entered office amid the mourning of his predecessor's death. As First Minister, he oversaw the introduction of free personal care for the elderly and initiated the Scottish Executive's response to the September 11 attacks in New York City.[1] He also implemented the McCrone Agreement for teachers in Scotland.[2] McLeish managed several task forces designed to improve the competitiveness of Scottish industry, especially the PILOT project for Scottish oil and gas supply chains.[3]

In his final months in office, McLeish was in a scandal involving allegations he sub-let part of his tax-subsidised Westminster constituency office without it having been registered in the register of interests kept in the Parliamentary office. Though McLeish could not have personally benefited financially from the oversight, he undertook to repay the £36,000 rental income. He resigned on 8 November 2001, having served only 1 year, 12 days.[4]

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Minister of State for Scotland (1997–1999)

Minister for Enterprise and Lifelong Learning (1999–2000)

First Minister of Scotland (1999–2000)

|

||

Bid for Scottish Labour leadership

The Inaugural First Minister, Donald Dewar, died on 11 October 2000 of a brain hemorrhage following a fall outside Bute House.[5][6] The office of First Minister was filled by Jim Wallace until the election of a new leader was elected.[7] The day after Dewar's funeral, McLeish launched his bid to be the next leader of the Labour Party in Scotland, with Jack McConnell later announcing his bid too.[8][9]

The ballot was held amongst a restricted electorate of Labour MSPs and members of Scottish Labour's national executive, because there was insufficient time for a full election to be held. McLeish defeated his rival Jack McConnell by 44 votes to 36 in the race to become the second first minister.[10][11][12][13]

Entering government

Nomination and appointment

On 26 October 2000, a vote to nominate a First Minister by the Scottish Parliament was held. McLeish won the parliament's approval for appointment, defeating John Swinney, leader of the Scottish National Party, David McLeitchie, leader of the Scottish Conservatives, and independent MSP, Dennis Canavan, by 68 to 33, 19 and 3, respectively. On the same day, McLeish was presented by Her Majesty the Queen with a Royal Warrant of Appointment and was officially sworn in at the Court of Session in Edinburgh.[14][15]

Cabinet

On the following day, McLeish formed his government. It was the continuation of the Labour-Liberal Democrat coalition that had existed under the Dewar government, with Jim Wallace remaining as Deputy First Minister. In the wake of the 2000 SQA exam controversy, he removed Sam Galbraith as education minister, replacing him with his leadership opponent McConnell. Wendy Alexander took over McLeish's former ministerial role, while Angus MacKay took McConnell's former finance portfolio.[16]

Tenure

Elderly care

Upon entering government as first minister, McLeish pledged that the Scottish Executive would fully embed a Royal Commission report on the care of elderly people which had recommended that the "state should pay all medical and personal care costs for older people". This was in contrast to the UK Government, who had previously ruled out similar proposals for similar to be implanted by the UK Government.[17] It was initially projected to cost an estimated £100 million per year for the Scottish Executive to pay for personal care of the elderly in Scotland, but it was deemed that it would "help prevent elderly people from having to spend their life savings or sell their homes to meet the cost of long term nursing bills".[17]

The announcement by McLeish highlighted the stark differences in policy between both the Scottish Executive and UK Government since the Scottish Parliament was re–established in 1999. Age Concern and Help the Aged charities welcomed the announcement by McLeish, with Help the Aged saying that "this bold move from Henry McLeish will encourage the government to reassess the viability and fairness of its current stance".[17]

Scotland's response to 9/11

McLeish led the Scottish Executive's response to the September 11 attacks in the United States.[18] He was initially concerned about Scotland's defence strategy and feared the country's major cities, such as Glasgow, Edinburgh and Aberdeen, would be targets based on their economic strength and significance to the Scottish, UK and European economies.[18]

In the immediate aftermath of the attacks in the United States, McLeish instructed all airports in Scotland to be on alert and tighten their security measures.[19] McLeish focussed on strengthening security, protection and defence systems in Scotland to ensure the country was equipped to deal with a large scale terrorist attack. McLeish led the then Scottish Executive to working with the UK Government to ensure appropriate measures and strengthen security was in place within Scotland.[18]

On September 13, 2001, McLeish moved a motion in the Scottish Parliament to send condolences to the people of the United States and New York.[19] Through the motion, McLeish said "the Parliament condemns the senseless and abhorrent acts of terrorism carried out in the United States yesterday and extends our deepest sympathies to those whose loved ones have been killed or injured".[20]

McLeish initially supported the War on Terror, however, twenty years on he regrets that the war ultimately turned out as a "war on Islam".[18]

Education

In 2001, McLeish pledged £10 million in education spending to provide books, equipment as well as providing homework materials for children across Scotland who were under looked after accommodation orders by local authorities. Additionally, McLeish committed to ensuring there was mainstream provision across Scotland's schools during his tenure as First Minister, stating that "part of our task is to provide mainstream provision, but it is also part of our task to top up provision, where we can, to reach children who suffer from a number of disadvantages", during a speech to the Scottish Parliament chamber on 25 November 2001.[21]

On education policy, one of the major achievements of McLeish's tenure as First Minister was the introduction of the McCrone agreement, the framework and agreement policy paper on teachers pay and working conditions across Scottish education and Scottish schools.[22]

Executive policy

McLeish failed in his attempt to rebrand the Scottish Executive as the Scottish Government. In 2007, the Scottish Executive did, however, later become known as the Scottish Government following the election victory of the SNP under Alex Salmond.[23]

Europe

During his tenure as First Minister, McLeish sought for Scotland to have a closer relationship and stronger voice in Europe, as well as the European Union.[24] McLeish appointed Jack McConnell, his eventual successor as First Minister, to further promote Scottish interests and Scotland in Europe and for external affairs across the European Union. A Scottish Executive press release highlighted "it is a top priority of the executive to engage constructively and thoroughly with the European Union, and with devolution, we are determined to make a step change in our level of engagement".[25]

Healthcare

McLeish claimed in September 2001 that "Scotland compares favourably with any other part of the United Kingdom. We have an important commitment to bringing down the average waiting time to nine months and an important commitment to planning ahead. If a situation arises in which it is appropriate to use private facilities, the Minister for Health and Community Care would want to do so". As First Minister, McLeish was highly critical of what he claimed was plans by the Scottish Conservative party to privatise NHS Scotland, as well as the SNP for "having no private sector involvement". Additionally, he claimed that health in Scotland was "important to all of us", and pledged his executive to "use private facilities where appropriate", claiming "that is important, and I am sure that it is a view that the Scottish people support".[26]

During his tenure as First Minister, McLeish long said that the Scottish Executive was in regular contact with Her Majesty's Government in London over the issue of personal care for the elderly. He made a commitment in 2001 that the Scottish Executive would "deliver full personal care to the people of Scotland". He further added "because of the publication of the report, we will be able to move soon to announcing the Executive's response to what I regard as an excellent paper. Discussions are on-going on a number of issues relating to the care development group report. Those discussions with Westminster are constructive and helpful".[27]

Spending on the NHS in Scotland during his time in office had been increased by £1.8 billion over the last three years. His executive invested in health services across Scotland, with McLeish advocating during First Ministers Questions in September 2001 "we are providing record sums to health authorities in Scotland. It is for health authorities to ensure equality of service, investment in staff and continuing refurbishment of infrastructure and buildings. That is what is happening. I repeat: the Executive is providing the health service with formidable sums of money. A massive commitment has been made by a coalition that believes in the NHS".[28]

Homelessness and mental health

As First Minister, McLeish appointed a health and homelessness co-ordinator. In September 2001, the Scottish Executive issued guidance to NHS Scotland that outlined their actions and views on how the NHS in Scotland "must take to address the health needs of homeless people, including those who have mental health problems". McLeish committed an increase in spending for NHS Scotland health boards to meet the demands of mental health, with health boards in Scotland receiving on average a 5.5% increase in spending in 2001. During a parliamentary speech in September 2001, McLeish stated that "greater priority is being given to mental health in Scotland, and the assumption is being made that people who are homeless have more problems than most. Over the next three years we intend to tackle both issues".[29]

Officegate scandal and resignation

In April 2001, reports emerged of McLeish receiving £4,000 annually from 1998 from the law firm Digby Brown, who were sub letting his constituency office in Glenrothes, Fife. Although the House of Commons Standards Commissioner questioned the reports, his spokesperson stated: "The matter has been dealt with. The income in question was not for Mr McLeish's personal use, it went straight into covering the costs of running the office.[30] The scandal would become known as theOfficegate scandal.[31]

In later October, McLeish released a statement in relation to paying £9,000 to the Fees Office at the House of Commons and the Presiding Officer of the Scottish Parliament, Sir David Steel, banned the debate of McLeish's financial records.[32] Steel had highlighted the situation was a matter of Westminster, not the Scottish Parliament. On 28 October, the Fife Constabulary announced its launch of an investigation following complaints made against McLeish and he refused to answer questions from reporters.[33]

By 2 November, the Leader of the Opposition at Holyrood, John Swinney, calls for McLeish's resignation after a "humiliating" appearance on the BBC's Question Time, when he admits he was unaware of the total sum of money involved.[34][35] On 6 November, it is emerged that the rental income for sub letting the office from 1987 was £36,122. McLeish claimed it was an "honest mistake" and offered to pay the remaining fees.[36] A survey by Scotland Today revealed, 77% of Scots believed he should resign as a result of the scandal.[37][31][38]

On the early hours of 8 November, McLeish tendered his resignation as First Minister of Scotland.[39][40] In a speech to the Scottish Parliament, McLeish admitted to making "mistakes" and that he "was at fault" for the Officegate scandal. During his resignation speech, McLeish was highly critical of the media and their role in his resignation, stating "what has surprised and dismayed me is how my family, friends, staff and colleagues have been brought into matters that are my responsibility alone". He further added that, despite being First Minister for just over twelve months, that he "would accept I have made no personal gain from any of this".[41]

Following his resignation as First Minister, McLeish continued to sit as an MSP in the Scottish Parliament for the Central Fife constituency.[41]

International visits

During his time in office, McLeish conducted a total of eight international visits.[42]

- One visit to: Italy (December 2000), United States (April 2001), Finland (September 2001), Taiwan (October 2001) and Japan (October 2001)

- Three visits to: Belgium (December 2000, May 2001 and October 2001)

See also

References

- ^ "Who have been Scotland's first ministers?". BBC News. 16 May 2016. Archived from the original on 20 May 2016.

- ^ "Henry McLeish's statement in full". The Guardian. 5 September 2002. Archived from the original on 14 September 2016.

- ^ Dewar's successor to seek more power for parliament Archived 21 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine, The Guardian, 23 October 2000.

- ^ "Scottish first minister resigns". the Guardian. 8 November 2001. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ "Donald Dewar dies after fall". The Independent. 10 October 2000. Retrieved 12 May 2022.

- ^ Leonard, Richard (11 October 2020). "Donald Dewar died 20 years ago today but his vision of social justice lives on". Daily Record. Retrieved 12 May 2022.

- ^ agencies, Staff and (11 October 2000). "Donald Dewar dies". the Guardian. Retrieved 12 May 2022.

- ^ "BBC NEWS | In Depth | Donald Dewar | Two in fight to succeed Dewar". news.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 12 May 2022.

- ^ "BBC NEWS | In Depth | Donald Dewar | Henry McLeish: Campaign statement". news.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ^ "BBC NEWS | UK | Scotland | McLeish faces first minister challenge". news.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 12 May 2022.

- ^ "BBC News | DONALD DEWAR | McLeish was leader in waiting". news.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 12 May 2022.

- ^ "BBC NEWS | In Depth | Donald Dewar | Leadership win for McLeish". news.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 12 May 2022.

- ^ "BBC NEWS | In Depth | Donald Dewar | McLeish aiming to steady ship". news.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 12 May 2022.

- ^ "BBC News | SCOTLAND | McLeish wins first minister title". news.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ "Scotland gets new First Minister". The Irish Times. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ "McLeish moves exam fiasco minister as he names new Scottish cabinet". The Independent. 30 October 2000. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ a b c Christie, Bryan (11 November 2000). "Older Scots to get free, long term care". BMJ: British Medical Journal. 321 (7270): 1176. PMC 1173469.

- ^ a b c d Ross, Calum (10 September 2021). "Henry McLeish feared Scotland was 'at risk' as September 11 attacks unfolded".

- ^ a b "*". www.parliament.scot.

- ^ "On this 9/11 anniversary, the need to become 'patriots of humanity' has never been more important - Henry McLeish". www.scotsman.com. 11 September 2021.

- ^ "Meeting of the Parliament: 25/10/2001". www.parliament.scot. Retrieved 4 May 2024.

- ^ "Meeting of the Parliament: 10/05/2001". www.parliament.scot. Retrieved 4 May 2024.

- ^ Cairney, Paul (2011). The Scottish Political System Since Devolution From New Politics to the New Scottish Government (PDF). Imprint Academic. ISBN 9781845402020. Retrieved 4 May 2024.

- ^ Cairney, Paul (2011). The Scottish Political System Since Devolution From New Politics to the New Scottish Government (PDF). Imprint Academic. ISBN 9781845402020. Retrieved 4 May 2024.

- ^ Cairney, Paul (2011). The Scottish Political System Since Devolution From New Politics to the New Scottish Government (PDF). Imprint Academic. ISBN 9781845402020. Retrieved 4 May 2024.

- ^ "Meeting of the Parliament: 20/09/2001". www.parliament.scot. Retrieved 4 May 2024.

- ^ "Meeting of the Parliament: 20/09/2001". www.parliament.scot. Retrieved 4 May 2024.

- ^ "Meeting of the Parliament: 20/09/2001". www.parliament.scot. Retrieved 4 May 2024.

- ^ "Meeting of the Parliament: 20/09/2001". www.parliament.scot. Retrieved 4 May 2024.

- ^ "McLeish standards inquiry dropped". 13 June 2001. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ a b "Q&A: Officegate". 6 November 2001. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ "McLeish pays back expenses". 23 October 2001. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ "Labour admits McLeish office 'error'". 30 October 2001. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ "McLeish fails to quell expenses row". 2 November 2001. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ "Pressure builds on first minister". 30 October 2001. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ "Taxman to probe 'Officegate'". 4 November 2001. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ "McLeish's exit: Timetable of events". 8 November 2001. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ "MPs' expenses at a glance". 7 November 2001. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ "BBC NEWS | In Depth | McLeish resignation". news.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ Millar, Frank. "Scottish leader quits in 'muddle not a fiddle'". The Irish Times. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ a b Glover, Julian; Tempest, Matthew (8 November 2001). "Scottish first minister resigns". The Guardian.

- ^ "International visits undertaken by First Ministers: FOI release". www.gov.scot. Retrieved 8 November 2024.