Prehistoric Italy

| History of Italy |

|---|

|

|

|

The prehistory of Italy refers to the period before the emergence of written historical sources and Roman dominance on the Italian Peninsula, spanning from the early Paleolithic through the Iron Age and into the broader pre-Roman period. During this time, human presence evolved from the earliest known hominins to increasingly complex societies engaged in agriculture, metallurgy, and trade. Shaped by climatic shifts and geographic changes, prehistoric communities developed distinct regional cultures and laid the groundwork for later civilizations such as the Etruscans and Romans.

Paleolithic

In prehistoric times, the landscape of the Italian Peninsula was significantly different from its modern appearance. During glaciations, for example, the sea level was lower and the islands of Elba and Sicily were connected to the mainland. The Adriatic Sea began at what is now the Gargano Peninsula, and what is now its surface up to Venice was a fertile plain with a humid climate.

The arrival of the first known hominins was 850,000 years ago at Monte Poggiolo.[1]

The presence of Homo neanderthalensis has been demonstrated in archaeological findings dating to c. 50,000 years ago (late Pleistocene). There are about 20 unique sites, the most important being that of the Grotta Guattari at San Felice Circeo, on the Tyrrhenian Sea south of Rome; another is at the grotta di Fumane (province of Verona) and the Breuil grotto, also in San Felice.

Homo sapiens sapiens appeared in Italy during the upper Palaeolithic: the earliest site on the peninsula, dated to 48,000 years ago, is Riparo Mochi.[2] In November 2011, tests conducted at the Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit in England on what were previously thought to be Neanderthal baby teeth, which had been unearthed in 1964 from the Grotta del Cavallo, dated the teeth to between 43,000 and 45,000 years ago.[3]

In 2011, the most ancient Sardinian complete human skeleton (called Amsicora) was discovered at Pistoccu in Marina di Arbus, dated to 8500 years ago during the transition period between the Mesolithic and Neolithic.[4]

Neolithic

The Neolithic period in Italy (approximately 6000–3600 BCE) represents a crucial transition from hunting and gathering to farming societies. During this time, communities established permanent settlements, domesticated plants and animals, and developed sophisticated ceramic and architectural traditions that connected the Italian peninsula to broader Mediterranean cultural networks.[5]

Early Neolithic communities in Italy are particularly known for their distinctive pottery traditions. Cardium pottery is a Neolithic decorative style that gets its name from the practice of imprinting the clay with the shell of Cardium edulis, a marine mollusk. The alternative name Impressed Ware is used by some archaeologists to define this culture, because impressions can be with other sharp objects, such as a nail or comb.[6] This pottery style is associated with some of the earliest farming communities in Italy, who lived in small villages of wooden or stone structures and practiced mixed agriculture and animal husbandry.[7]

Cardium pottery is found in the zone "covering Italy to the Ligurian coast" as distinct from the more western Cardial beginning in Provence, France and extending to western Portugal. The main culture of the Mediterranean Neolithic, which eventually extended from the Adriatic sea to the Atlantic coasts of Portugal and south to Morocco, is also referred to as "cardial ware".[8] These widespread ceramic traditions demonstrate the maritime connections that linked Neolithic communities across the Mediterranean basin.

In the Middle and Late Neolithic (c. 5000-3500 BCE), more regionally distinct cultures emerged across Italy, including the elaborately decorated pottery of the Serra d'Alto culture in southern Italy and the Square-Mouthed Pottery culture in the north.[9] Social complexity increased during this period, with evidence for craft specialization, long-distance trade networks, and more pronounced social hierarchies.

Since the Late Neolithic, Aosta Valley, Piedmont, Liguria, Tuscany and Sardinia in particular were involved in the pan-Western European Megalithic phenomenon. These structures, including stone circles, menhirs, and dolmens, likely served ceremonial and funerary purposes, reflecting complex belief systems and social organization.[10] Later, in the Bronze Age, megalithic structures were built also in Latium, Puglia and Sicily.[11] Around the end of the third millennium BCE, Sicily imported from Sardinia typical cultural aspects of the Atlantic world, including the construction of small dolmen-shaped structures that reached all over the Mediterranean basin.[12] These developments illustrate how Italian communities participated in broader European cultural networks while developing distinctive regional traditions.

The increasing complexity of social structures, along with early experimentation in metallurgy, marked the gradual transition from the Neolithic way of life to the Copper Age across the Italian peninsula.

Copper Age

The Copper Age in the Italian Peninsula, is generally dated from c. 3600 BCE to c. 2200 BCE,[13][14] encompassing the emergence of metallurgy,[15][16] complex burial practices,[17][18] and transitional cultures like the Remedello,[19] Rinaldone[20] and Gaudo cultures.[21] They are sometimes described as Eneolithic cultures, due to their use of copper tools.

Recent scholarship has identified significant social transformations during this period, with evidence suggesting the emergence of early forms of social inequality and specialized craft production.[22][23] Metallographic analyses of copper artifacts reveal that artisans employed sophisticated casting, annealing, and cold-working techniques, indicating specialized knowledge transmission networks across communities.[24][25] These technological developments challenged earlier assumptions about 'primitive' metallurgy and contributed to changing social dynamics.[15]

Copper mining began in the middle of the 4th millennium BC in Liguria with the Libiola and Monte Loreto mines, which are dated to 3700 BCE. These are the oldest copper mines in the western Mediterranean basin.[26]

Regional Cultural Expressions

The Italian Copper Age exhibits considerable regional diversity while maintaining certain shared characteristics. Key regional expressions include the Laterza culture in southern Apulia and Basilicata, characterized by distinctive ceramic forms and burial practices; the Abealzu-Filigosa culture in Sardinia with its megalithic architecture; the Conelle-Ortucchio culture in Abruzzo and Marche, known for fortified settlements; the Serraferlicchio culture in Sicily with its painted ceramics; and the Spilamberto group in Emilia-Romagna, distinguished by its elaborate burial practices.[27] The Remedello culture in northern Italy shows distinct influences from Central European traditions, while the Rinaldone and Gaudo cultures share certain burial practices despite their geographic separation.[28]

Regional diversity in material culture reflects complex patterns of exchange networks spanning the Italian peninsula and beyond, with evidence of long-distance trade in Alpine copper, flint, and obsidian.[29] These networks facilitated not only the movement of raw materials and finished objects but also the transmission of technological knowledge and social practices, contributing to both regional distinctiveness and broader cultural connections.[30]

Social Organization and Settlement Patterns

Settlement patterns during the Italian Copper Age show increased territorial control and social stratification, with evidence of fortified hilltop settlements emerging alongside dispersed farming communities.[31][32] Subsistence strategies reflect diversification, with specialized animal husbandry focusing on secondary products (milk, wool) complementing intensified cereal agriculture, as demonstrated by archaeozoological and archaeobotanical analyses from sites across the peninsula.[33] These developments coincided with population growth and environmental modifications, including forest clearance and early forms of landscape management that would accelerate during the subsequent Bronze Age.

Mortuary evidence demonstrates increasing social differentiation, with elite burials containing copper daggers, stone battle-axes, and ornaments made of exotic materials suggesting the emergence of warrior identities and status competition.[34][35] At sites like Ponte San Pietro and Fontanella Mantovana, spatial organization of graves and differential treatment of individuals further indicates complex social hierarchies developing alongside new ideological expressions.[36][37]

Statue Menhirs and External Connections

The earliest Statue menhirs in northern Italy and Sardinia date to the Copper Age and frequently depict stylized anthropomorphic figures bearing weapons such as daggers and axes. These carved stones are interpreted as expressions of emerging social identities, possibly linked to warrior elites. Some scholars have proposed distant iconographic parallels with sculptural traditions from the Pontic–Caspian steppe, including the Yamna culture, although direct cultural transmission remains debated.[38] The statue menhir tradition persisted in parts of the Italian peninsula into the Bronze Age and, in some cases, into the Iron Age.[39]

The Italian Copper Age developed in parallel with similar phenomena across Europe, though with distinctive regional characteristics. While Central European metallurgical traditions likely influenced northern Italian developments, the emergence of metalworking in peninsular Italy appears to have followed somewhat independent trajectories.[40] The Italian peninsula's position at the center of Mediterranean exchange networks facilitated contacts with the Balkans, Central Europe, and possibly the Eastern Mediterranean, contributing to the mosaic of cultural traditions visible in the archaeological record.[41]

Environmental data from lake sediments and archaeobotanical remains indicate targeted forest clearance episodes and intensified agricultural strategies during the mid-third millennium BCE, suggesting demographic pressure and territorial competition that likely contributed to social transformations.[42][43] These ecological changes coincided with shifting settlement patterns, possibly reflecting adaptation strategies to changing resource availability and social pressures.

The Bell Beaker culture marks the transition between the Copper Age and the early Bronze Age.

- Bell Beaker culture ceramic vessel

- Anthropomorphic stele from St-Martin-de-Corléans, Bell Beaker culture

- Engravings of Remedello-type daggers at Valcamonica

- Axe, Rinaldone culture

Bronze Age

The Italian Bronze Age is conditionally divided into four periods:

| The Early Bronze Age | 2300–1700 B.C |

| The Middle Bronze Age | 1700–1350 B.C |

| The Recent Bronze Age | 1350–1150 B.C |

| The Final Bronze Age | 1150–950 B.C |

Bell Beaker Culture in Italy

The Bell Beaker culture, which spread across much of Western and Central Europe during the late 3rd millennium BCE, is also attested in various parts of the Italian Peninsula. Archaeological evidence shows that Bell Beaker materials appeared primarily in the northwestern and southwestern regions of Italy, including Liguria, Tuscany, and parts of Sicily.[44]

In Italy, the Bell Beaker phenomenon is characterized by distinctive pottery forms, archery-related grave goods, and metallurgy. Burial practices tend to follow individual inhumation patterns often accompanied by wristguards, copper daggers, and bell-shaped vessels, although regional variations exist.[45] Sites such as Fontanella Mantovana and Ponte San Pietro in northern Italy have yielded diagnostic Beaker-style ceramics and associated metal artifacts.[46]

Genetic studies suggest that the Bell Beaker expansion in Central and Western Europe was associated with significant population movements linked to Steppe-related ancestry, particularly carriers of the Y-DNA haplogroup R-M269.[47] However, the demographic impact in Italy appears to have been more complex. Recent archaeogenetic research shows more continuity with earlier Neolithic populations in central and southern Italy, with a modest influx of Steppe ancestry, particularly in northern regions.[48][49]

This pattern suggests that while the Bell Beaker culture in Italy shared material traits with broader European Beaker networks, its spread was shaped by a combination of cultural diffusion and selective migration, rather than a large-scale population replacement seen in other regions.[50]

The Early Bronze Age shows the beginning of a new culture in Northern Italy and is distinguished by the Polada culture. Polada settlements were mainly widespread in wetland locations such as around the large lakes and hills along the Alpine margin. The cities of Toppo Daguzzo and La Starza were known as the center of the Proto-Apennine stage of Palma Campania culture spread in southern Italy at this time.[51]

The Middle Bronze Age known as the Apennine Bronze Age in Central and Southern Italy was the period when settlements were established both on lowland and upland areas. Hierarchy among the social groups was experienced during this period according to the evidence of the tombs. The two-tier grave found at Toppo Daguzzo is an example of elite groups growth. On the top level, nearly 10 fractured skeletons have been found without any grave objects, while at the lower level eleven burials were found accompanied by different valuable pieces: 6 males with bronze weapons, 4 females with beads and a child.[51][52] The Middle Bronze Age in Northern Italy was characterised by the Terramare culture.

The Recent Bronze Age, known as the Sub-Apennine period in Central Italy, is a frame of time when sites relocated to defended locations. At this time settlement hierarchy obviously appeared in cities such as Latium and Tuscany.[51]

The Final Bronze Age is the period during which the majority of the Italian peninsula was united in the Proto-Villanovan culture. Pianello di Genga is an exception to the small cemeteries characterized for the Protov-Villanovan culture. More than 500 burials were found in this cemetery which is known for its two centuries of usage by different communities.[51][53]

Polada culture

The Polada culture (Polada is a locality near Brescia) was a cultural horizon extended from eastern Lombardy and Veneto to Emilia and Romagna, formed in the first half of 2nd millennium BC perhaps for the arrival of new people from the transalpine regions of Switzerland and Southern Germany.[54]

The settlements were usually made up of stilt houses; the economy was characterized by agricultural and pastoral activities, hunting and fishing were also practiced as well as the metallurgy of copper and bronze (axes, daggers, pins etc.). Pottery was coarse and blackish.[55]

It was followed in the Middle Bronze Age by the facies of the pile dwellings and of the dammed settlements.[56]

Nuragic civilization

Located in Sardinia (with ramifications in southern Corsica), the Nuragic civilization, who lasted from the early Bronze Age (18th century B.C.) to the second century A.D. when the island was already Romanized, evolved during the Bonnanaro period from the preexisting megalithic cultures that built dolmens, menhirs, more than 2,400 Domus de Janas and also the imponent altar of Monte d'Accoddi.

It takes its name from the characteristic Nuraghe. The nuraghe towers are unanimously considered the best-preserved and largest megalithic remains in Europe. Their effective use is still debated; while most scholars considered them as fortresses, others see them as temples.

A warrior and mariner people, the ancient Sardinians held flourishing trades with the other Mediterranean peoples. This is shown by numerous remains contained in the nuraghe, such as amber coming from the Baltic Sea, small bronze figures portraying African beasts, oxhide ingots and weapons from Eastern Mediterranean, Mycenaean ceramics. It has been hypothesized that the ancient Sardinians, or part of them, could be identified with the Sherden, one of the so-called People of the Sea who attacked ancient Egypt and other regions of eastern Mediterranean.[57]

Other original elements of the Sardinian civilization include the temples known as "Holy wells", dedicated to the cult of the holy waters, the Giants' graves,[58] the Megaron temples, several structures for juridical and leisure functions and numerous bronze statuettes, which were discovered even in Etruscan tombs, suggesting a strong relationships between the two peoples. Another important element of this civilization are the Giants of Mont'e Prama,[59] perhaps the oldest anthropomorphic statues of the western Mediterranean sea.

Sicily

Among the most important cultural expressions born in Sicily during the Bronze Age the cultures of Castelluccio (Ancient Bronze Age) and of Thapsos (Middle Bronze Age) are worth noting. Both originated in the southeastern part of the island. In these cultures, in particular in the Castelluccio phase, there are obvious influences from the Aegean Sea, where the Helladic civilization was flourishing.

Some small monuments date back to this phase, used as tombs and found almost everywhere, both inland and along the coasts of this region.[60]

Belonging to a western (Iberian-Sardinian) type is the Bell Beaker culture known from sites on the northwestern and southwestern coasts of Sicily, previously occupied by the Conca d'Oro culture, while in the late Bronze Age there are signs in northeastern Sicily of cultural osmosis with the people of the peninsula that led to the appearance of Proto-Villanovan culture at Milazzo, perhaps linked to the arrival of Sicels.[61]

The nearby Aeolian Islands hosted the flourishing of the Capo Graziano and Milazzo cultures in the Bronze Age, and subsequently that of Ausonio (divided into two phases, I and II).[62]

Palma Campania culture

The Palma Campania culture took shape at the end of the third millennium BCE and represents the Early Bronze Age of Campania. It is named for the locality of Palma Campania where the first findings were made.

Many villages belonging to this culture were buried under volcanic ash after an eruption of Mount Vesuvius that took place around or after 2000 BCE.[63]

Apennine culture

The Apennine culture is a cultural complex of central and southern Italy that, in its broadest sense (including the preceding Protoapennine B and following Subapennine facies), spans the Bronze Age. In the narrower sense more commonly used today, it refers only to the later phase of the Middle Bronze Age in the 15th and 14th centuries BCE.[64]

The people of the Apennine culture were, at least in part, cattle herdsmen grazing their ungulates over the meadows and groves of mountainous central Italy, including on the Capitoline Hill at Rome, as shown by the presence of their pottery in the earliest layers of occupation. The primary picture is of a population that lived in small hamlets located in defensible places. There is evidence that herdsmen, when traveling between summer pastures, built temporary camps or lived in caves and rock shelters. However, their range was not confined to the hills, nor was their culture confined to herding cattle, as shown by sites like Coppa Nevigata, a well-defended and somewhat sizeable coastal site where a variety of subsistence strategies were practiced alongside advanced industries such as dye production.

Terramare

The Terramare was a Middle and Recent Bronze Age culture, between the 16th and the 12th centuries B.C., in the area of what is now Pianura Padana (specially along the Panaro river, between Modena and Bologna).[65] Their total population probably reached an impressive peak of more than 120,000 individuals near the beginning of the Recent Bronze Age.[66] In the early period they lived in villages with an average population of about 130 people living in wooden stilt houses: they had a square shape, built on land but generally near a stream, with roads that crossed each other at right angles. Over the lifetime of the Terramare culture, these settlements developed into stratified zones with larger settlements of up to 15-20Ha (approximately 1500-2000 people) surrounded by smaller villages. Especially in the later period, the proportion of settlements that were fortified approaches 100%.

Around the 12th century BC the Terramare system collapsed, the settlements were abandoned and the populations moved southward, where they mingled with the Apennine peoples.[65] The influence of this population abandoning the Po valley and moving south may have formed the basis of the Tyrrhenian culture, ultimately leading to the historic Etruscans, based on a surprising level of correspondence between archeological evidence and early legends recorded by the Greeks.[65]

Castellieri

The Castellieri culture developed in Istria during the developed Early and Middle Bronze Age, and later expanded into Friuli, the modern Venezia Giulia, Dalmatia and the neighbouring areas.[67] It lasted for more than a millennium, from the 15th century BC until the Roman conquest in the third century BC. It takes its name from the fortified boroughs (Castellieri, Friulian cjastelir) which characterized the culture.

The ethnicity of the Castellieri civilization is uncertain, although it was most likely of Pre-Indoeuropean stock, coming from the sea. The first Castellieri were indeed built along the Istrian coast and show a similar Cyclopean masonry which is also characterizing in the Mycenaean civilization at the time.The best researched Castelliere in Istria is Monkodonja near Rovinj. Hypotheses about an Illyrian origin of the people are not confirmed.

The Castellieri were fortified settlements, usually located on hills or mountains or, more rarely (such as in Friuli), in plains. They were constituted by one or more concentric series of walls, of rounded or elliptical shape in Istria and Venezia Giulia, or quadrangular in Friuli, within which was the inhabited area.

Some hundred Castellieri have been discovered in Istria, Friuli, and Venezia Giulia, such as that of Leme, in west-central Istria, of Elerji, near Muggia, of Monte Giove near Prosecco (Trieste) and San Polo, not far from Monfalcone. However, the largest castelliere was perhaps that of Nesactium, in southern Istria, not far from Pula.

Canegrate culture

The Canegrate culture developed from the mid-Bronze Age (13th century BC) until the Iron Age in the Pianura Padana, in what is now western Lombardy, eastern Piedmont and Ticino. It takes its name from the township of Canegrate where, in the 20th century, some fifty tombs with ceramics and metal objects were found. It represents the first migratory wave of the proto-Celtic[68] population from the northwest part of the Alps that, through the Alpine passes, had already penetrated and settled in the western Po valley between Lake Maggiore and Lake Como (Scamozzina culture). They brought a new funerary practice—cremation—which supplanted inhumation.[69]

Canegrate terracotta is very similar to that known from the same period north to the Alps (Provence, Savoy, Isère, Valais, the area of Rhine-Switzerland-eastern France). The members of the culture have been described as a warrior population who had descended to Pianura Padana from the Swiss Alps passes and the Ticino.

Proto-Villanovan culture

It was a culture of the end of the Bronze Age (12th-10th century BC), widespread in much of the Italian peninsula and north-eastern Sicily (including the Aeolian Islands), characterized by the funeral ritual of incineration. The ashes of the deceased were placed into biconical urns decorated with geometric patterns. Their settlements were often located on the top of the hills and protected by stone walls.[70]

Luco-Meluno culture

The Luco-Meluno culture emerged during the transitional period between the Bronze Age and Iron Age, and occupied Trentino and part of South Tyrol. It was succeeded in the Iron Age by the Fritzens-Sanzeno culture.

Iron Age

Villanova culture

The name of this Iron Age civilization derives from a locality in the frazione Villanova of Castenaso, Città metropolitana di Bologna, in Emilia, where a necropolis was discovered by Giovanni Gozzadini in 1853–1856. It succeeded the Proto-Villanovan culture during the Iron Age in the territory of Tuscany and northern Lazio and spread in parts of Romagna, Campania and Fermo in the Marche.

The main characteristic of the Villanovans (with some similarities with the Proto-Villanovan period of the late Bronze Age) were cremation burials, in which the deceased's ashes were housed in bi-conical urns and buried. The burial characteristics relate the Villanovan culture to the Central European Urnfield culture (c. 1300–750 BCE) and the successive Hallstatt culture.

The Villanovans were initially devoted to agriculture and animal husbandry, with a simplified social order. Later, specialized craftsmanship activities such as metallurgy and ceramics caused the accumulation of wealth, which resembled the appearance of social stratification.

Latial culture

The Latial culture ranged approximately over ancient Old Latium. The Iron Age Latial culture coincided with the arrival in the region of a people who spoke Old Latin. The culture was likely therefore to identify a phase of the socio-political self-consciousness of the Latin tribe, during the period of the kings of Alba Longa and the foundation of the Roman Kingdom.

Este culture

The Este culture or Atestine culture was an Iron Age archaeological culture existing from the late Italian Bronze Age (10th-9th century BCE, proto-Venetic phase) to the Roman period (1st century BCE). It was located in the present territory of Veneto in Italy and derived from the earlier and more extensive Proto-Villanovan culture.[71] It is also called "civilization of situlas", or paleo-Venetic.

Golasecca culture

The Golasecca culture emerged during the early Iron Age in the northwestern Po plain. It takes its name from Golasecca, a locality next to the Ticino where, in the early 19th century, abbot Giovanni Battista Giani excavated its first findings (some fifty tombs with ceramics and metal objects). Remains of the Golasecca culture span an area of roughly 20,000 square kilometers south of the Alps and between the Po, Sesia and Serio rivers, dating from the ninth to the fourth century BCE.

Their origins can be directly traced from that of Canegrate and to the so-called Proto-Golasecca culture (12th–10th centuries BC). The Golasecca culture traded with the Etruscans and the Hallstatt culture on the north, later reaching the Greek world (oil, wine, bronze objects, ceramics and others) and northern Europe (tin and amber from the Baltic coast).

In a Golasecca culture tomb in Pombia, researchers found the oldest known remains of common hop beer in the world.

Fritzens-Sanzeno culture

The Fritzens-Sanzeno culture is attested in the late Iron Age, from the sixth to the first century BC, in the Alpine region of Trentino and South Tyrol; in the period of maximum expansion it reached into the Engadin region.

The Camuni

The Camuni were an ancient people of uncertain origin (according to Pliny the Elder, they were Euganei; according to Strabo, they were Rhaetians) who lived in Val Camonica – in what is now northern Lombardy – during the Iron Age, although human groups of hunters, shepherds and farmers are known to have lived in the area since the Neolithic.

They reached the height of their power during the Iron Age due to the presence of numerous iron mills in Val Camonica. Their historical importance is, however, mostly due to their legacy of carved rocks, c. 300,000 in number, which date from the Palaeolithic to the Middle Ages.

Pre-Roman period

Villanovan-Etruscan Development (950–500 BCE)

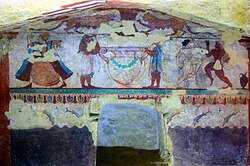

The Early Iron Age in Italy (c. 950–750 BCE) was marked by the emergence of the Villanovan culture, now widely recognized as the earliest phase of Etruscan civilization.[72] This culture, named after the archaeological site of Villanova near Bologna, was characterized by distinctive cremation burials, geometric pottery designs, and advanced bronze and iron metallurgy.[73] Starting from the 8th century BCE, this culture developed into the more urbanized Etruscan civilization, which created a network of powerful city-states across Etruria (modern Tuscany, western Umbria, and northern Lazio).[74]

The Etruscans developed sophisticated urban planning, hydraulic engineering (including drainage systems and aqueducts), and monumental architecture.[75] Their society was organized into independent city-states like Tarquinia, Veii, Caere (modern Cerveteri), and Vulci, which formed loose confederations for religious and military purposes.[76] Despite extensive archaeological evidence, the origins of this non-Indo-European people remain debated among scholars, with theories ranging from indigenous development to migration from Asia Minor.[77] From their original homeland on the Tyrrhenian coast of central Italy, they expanded to northern Italy (particularly the Po Valley) and south to Campania, establishing an extensive trade network and cultural influence that profoundly shaped early Rome and the Latin world.[78]

Greek Colonization and Mediterranean Connections

From the 8th century BCE, Greek colonists established numerous city-states along coastal southern Italy and Sicily in a region that became known as Magna Graecia (Greater Greece).[79] Major colonies included Syracuse, Naples (Neapolis), Tarentum, and Cumae, which maintained close connections with their mother cities while developing distinct local characteristics.[80] These colonies introduced urban planning based on the grid system, monumental temple architecture, coinage, and alphabetic writing to the Italian peninsula.[81]

The Greek presence fostered intensive cultural exchange with indigenous populations, particularly affecting the Etruscans who adopted and adapted Greek mythological themes, artistic styles, and technological innovations.[82] This led to the formation of extensive Mediterranean trade networks that connected Italy with Greece, North Africa, and the Near East, transforming the Italian peninsula from a relatively isolated region into a crossroads of Mediterranean cultures.[83]

The Phoenicians similarly established trading posts and colonies in western Sicily and Sardinia, creating further cultural connections and sometimes competing with Greek interests.[84]

Indigenous Peoples and Political Structures

While the Etruscans and Greeks created urban civilizations, numerous other peoples inhabited the Italian peninsula, mostly of Indo-European origin, organized in various political structures:[85]

- The Latins in Latium formed the Latin League, a religious and military confederation of about 30 communities sharing cultural and linguistic ties. From this group emerged the Roman civilization.[86]

- The Samnites in southern Abruzzo, Molise and Campania formed a powerful confederation of four tribes (Pentri, Caraceni, Caudini, and Hirpini) that would later challenge Roman expansion.[87]

- Umbri in Umbria and northern Abruzzo

- Sabellians, Falisci, Volsci and Aequi in Latium

- Piceni in the Marche and north-east Abruzzo

- Daunians, Messapii and Peucetii (forming the Apulian or Iapygian confederation) in Apulia

- Lucani and Bruttii in the southern tips of the peninsula

- The Sicels, Elymians and Sicani in Sicily[88]

- The Nuragic peoples, still inhabiting Sardinia

In northern Italy, populations included the Ligurians (an Indo-European people who lived in what is now Liguria, southern Piedmont and the southern French coast), the Lepontii, Insubres, Orobii and other Celtic tribes in Piedmont and Lombardy, and the Veneti of north-eastern Italy. Beginning in the 4th century BCE, new tribes of Celts (including the Senones, Boii, and Lingones) migrated into northern Italy, establishing settlements in the Po Valley and occasionally launching raids southward.[89]

This complex mosaic of peoples engaged in ever-changing relationships of trade, alliance, and conflict. Their interactions created a dynamic political landscape from which Rome would eventually emerge as the dominant power by the 3rd century BCE.[90]

See also

References

- ^ "Erano padani i primi abitanti d'Italia". National Geographic (in Italian). 20 January 2012. Archived from the original on 26 June 2019. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ^ 42.7–41.5 ka (1σ CI). Katerina Douka et al., A new chronostratigraphic framework for the Upper Palaeolithic of Riparo Mochi (Italy), Journal of Human Evolution 62(2), 19 December 2011, 286–299, doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2011.11.009.

- ^ John Noble, Wilford (2 November 2011). "Fossil Teeth Put Humans in Europe Earlier Than Thought". New York Times. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- ^ "Stone Pages Archaeo News: Found Amsicora: the oldest Sardinian". www.stonepages.com. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ^ Malone, Caroline (2003). "The Italian Neolithic: A Synthesis of Research". Journal of World Prehistory. 17 (3): 235–312. doi:10.1023/B:JOWO.0000012729.36053.42.

- ^ Fagan, Brian M., ed. (1996). The Oxford Companion to Archaeology. Oxford University Press. pp. 89–90. ISBN 978-0195076189.

- ^ Pessina, Andrea; Tiné, Vincenzo (2018). "Recent developments in the study of the Italian Neolithic". Documenta Praehistorica. 45: 58–67. doi:10.4312/dp.45.6.

- ^ A. Gilman, 1974, Neolithic of Northwest Africa, Antiquity,vol 48, no. 192, pp 273-282.

- ^ Whitehouse, Ruth (1992). Underground Religion: Cult and Culture in Prehistoric Italy. University of London. pp. 45–67.

- ^ Renfrew, Colin (1990). Before Civilization: The Radiocarbon Revolution and Prehistoric Europe. Cambridge University Press. pp. 123–144. ISBN 978-0521387323.

- ^ "Artepreistorica.com | MEGALITISMO DOLMENICO DEL SUD-EST ITALIA NELL´ETA´ DEL BRONZO". Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ^ S. Piccolo, Ancient Stones: The Prehistoric Dolmens of Sicily, 2018, Abacus Academic Press, pp. 31 onwards.

- ^ Dolfini, A. (2020). "From the Neolithic to the Bronze Age in central Italy: Settlement, burial, and social change at the dawn of metal production". Journal of Archaeological Research, 28(2), 229-287. doi:10.1007/s10814-019-09134-9

- ^ Maggi, R., & Pearce, M. (2005). "Mid fourth-millennium copper mining in Liguria, north-west Italy: The earliest known copper mines in Western Europe". Antiquity, 79(303), 66-77. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00113705

- ^ a b Dolfini, A. (2013). "The emergence of metallurgy in the central Mediterranean region: A new model". European Journal of Archaeology, 16(1), 21-62. doi:10.1179/1461957112Y.0000000023

- ^ Giardino, C. (2019). "Pre-Roman mining and metallurgy in Italy: State of research and recent advances". In G. Artioli, M. Pearce, & P. Piccardo (Eds.), Metals, Metalloids and Minerals in Prehistoric Italy (pp. 55-74). Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-11622-2_4

- ^ Miari, M. (2014). "Le necropoli eneolitiche della Romagna". In D. Cocchi Genick (Ed.), Critères de définition des faciès culturels de l'Âge du cuivre en Italie (pp. 137-148). Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria.

- ^ Dolfini, A. (2006). "Embodied inequalities: Burial and social differentiation in Copper Age central Italy". Archaeological Review from Cambridge, 21(2), 58-77.

- ^ De Marinis, R. C. (2013). "La necropoli di Remedello Sotto e l'età del Rame nella pianura padana a nord del Po". In R. C. De Marinis (Ed.), L'età del Rame: La pianura padana e le Alpi al tempo di Ötzi (pp. 301-351). Compagnia della Stampa.

- ^ Negroni Catacchio, N. (2006). "La cultura di Rinaldone". In N. Negroni Catacchio (Ed.), Pastori e guerrieri nell'Etruria del IV e III millennio a.C. (pp. 31-45). Centro Studi di Preistoria e Archeologia.

- ^ Bailo Modesti, G., & Salerno, A. (1998). Pontecagnano II.5. La necropoli eneolitica. Istituto Universitario Orientale.

- ^ Dolfini, A. (2020). "From the Neolithic to the Bronze Age in Central Italy: Settlement, Burial, and Social Change at the Dawn of Metal Production". Journal of Archaeological Research, 28(3), 229-287.

- ^ Pearce, M. (2019). "The 'Copper Age'—A History of the Concept". Journal of World Prehistory, 32(3), 229-250.

- ^ Dolfini, A., Angelini, I., & Artioli, G. (2021). "Copper to Tuscany–Coals to Newcastle? The dynamics of metalwork exchange in early Italy". PLOS ONE, 16(1), e0227259.

- ^ Artioli, G., Angelini, I., Nimis, P., & Villa, I. M. (2017). "A lead-isotope database of copper ores from the Southeastern Alps: A tool for the investigation of prehistoric copper metallurgy". Journal of Archaeological Science, 75, 27-39.

- ^ "Monte Loreto. Fourth-millennium cal BC mineshaft (ML6)". Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ^ Negroni Catacchio, N. (2014). "Italy during the Copper Age". In C. Fowler, J. Harding, & D. Hofmann (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Neolithic Europe (pp. 573-594). Oxford University Press.

- ^ Cocchi Genick, D. (2008). "La tipologia in funzione della ricostruzione storica. Le forme vascolari dell'età del rame dell'Italia centrale". Rivista di Scienze Preistoriche, 58, 125-186.

- ^ Pearce, M. (2015). "The spread of early copper mining and metallurgy in Europe: An assessment of the diffusionist model". In J. Kerner, J. K. Dann, & P. Bangsgaard (Eds.), Climate and Ancient Societies (pp. 181-195). Museum Tusculanum Press.

- ^ Dolfini, A., & Giardino, C. (2015). "The role of metal weapons and tools in constructing social identities in final Neolithic/Copper Age Italy". Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology, 28(1), 3-22. doi:10.1558/jmea.v28i1.27503

- ^ Barfield, L. H. (2001). "Beaker lithics in northern Italy". In F. Nicolis (Ed.), Bell Beakers Today: Pottery, People, Culture, Symbols in Prehistoric Europe (pp. 507-518). Provincia Autonoma di Trento.

- ^ Cazzella, A., & Guidi, A. (2011). "The chronology of the Copper and Bronze Ages in central and southern Italy". Rivista di Scienze Preistoriche, 61, 201-252.

- ^ Pessina, A., & Tiné, V. (2008). Archeologia del Neolitico: L'Italia tra VI e IV millennio a.C. Carocci Editore.

- ^ Keates, S. (2002). "The Flashing Blade: Copper, Colour and Luminosity in North Italian Copper Age Society". In A. Jones & G. MacGregor (Eds.), Colouring the Past: The Significance of Colour in Archaeological Research (pp. 109-125). Oxford: Berg.

- ^ De Marinis, R. C. (2013). "La necropoli di Remedello Sotto e l'età del Rame nella pianura padana a nord del Po". In R. C. De Marinis (Ed.), L'età del Rame: La Pianura Padana e le Alpi al tempo di Ötzi (pp. 301-351). Brescia: Compagnia della Stampa.

- ^ Dolfini, A. (2015). "Neolithic and Copper Age mortuary practices in the Italian peninsula: Change of meaning or change of medium?". In C. Fowler, I. Harding, & D. Hofmann (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Neolithic and Bronze Age Europe (pp. 325-346). Oxford University Press.

- ^ Anzidei, A. P., Carboni, G., & Mieli, G. (2018). "The Eneolithic necropolis of Osteria del Curato-via Cinquefrondi: new data from Rome (Italy)". In H. Meller, D. Gronenborn, & R. Risch (Eds.), Überschuss ohne Staat–Politische Formen in der Vorgeschichte (pp. 397-418). Halle: Landesamt für Denkmalpflege und Archäologie Sachsen-Anhalt.

- ^ "La società dell'età del Rame nell'area alpina e prealpina (2013)". www.academia.edu. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ^ "Museo delle Statue Stele Lunigianesi – Le statue stele in Italia e in Europa". Archived from the original on 13 May 2014. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ^ Pearce, M. (2007). "Bright blades and red metal: Essays on north Italian prehistoric metalwork". Accordia Specialist Studies on Italy, 14.

- ^ Robb, J. (2007). The Early Mediterranean Village: Agency, Material Culture, and Social Change in Neolithic Italy. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Cremaschi, M., Mercuri, A. M., Torri, P., Florenzano, A., Pizzi, C., Marchesini, M., & Zerboni, A. (2016). "Climate change versus land management in the Po Plain (Northern Italy) during the Bronze Age: New insights from the VP/VG sequence of the Terramara Santa Rosa di Poviglio". Quaternary Science Reviews, 136, 153-172.

- ^ Mercuri, A. M., Florenzano, A., Burjachs, F., Giardini, M., Kouli, K., Masi, A., Picornell-Gelabert, L., Revelles, J., Sadori, L., Servera-Vives, G., Torri, P., & Fyfe, R. (2019). "From influence to impact: The multifunctional land use in Mediterranean prehistory emerging from palynology of archaeological sites (8.0-2.8 ka BP)". The Holocene, 29(5), 830-846.

- ^ Heyd, V. (2007). "Europe 2500 to 2200 BC: Between Expanding Ideologies and the Consolidation of Power." In: Kienlin, T. L. & Zimmermann, A. (eds.), *Beyond Elites: Alternatives to Hierarchical Systems in Modelling Social Formations*, pp. 133–143.

- ^ Salanova, L. (2001). "The Bell Beaker phenomenon and the Neolithic-Bronze Age transition in Europe." In: *Journal of European Archaeology*, 4(2), 103–115.

- ^ De Marinis, R.C. (2003). "La facies a campaniforme nel quadro della prima età del Bronzo italiana." In: *Preistoria Alpina*, 39, 195–216.

- ^ Olalde, I. et al. (2018). "The Beaker phenomenon and the genomic transformation of northwest Europe." *Nature*, 555, 190–196.

- ^ Antonio, M. L. et al. (2019). "Ancient Rome: A genetic crossroads of Europe and the Mediterranean." *Science*, 366(6466), 708–714.

- ^ Fernandes, D. et al. (2020). "A genetic history of the pre-contact Caribbean." *Nature*, 590, 103–110.

- ^ Heyd, V. & Knipper, C. (2022). "The Beaker phenomenon: A synthesis of archaeological and bioarchaeological research." In: Fokkens, H. & Harding, A. (eds.), *The Oxford Handbook of the European Bronze Age*, Oxford University Press.

- ^ a b c d ANCIENT EUROPE 8000 B.C.–A.D. 1000, ANCIENT EUROPE 8000 B.C.–A.D. 1000 (2003). Ancient Europe 8000 B.C.-A.D.1000: Encyclopedia of the Barbarian World (PDF). Charles Scribner's Sons. ISBN 0684806681. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 January 2016. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "The Italian Bronze Age | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- ^ "ITALIA".

- ^ Bietti Sestieri 2010, p. 21.

- ^ "Treccani - La cultura italiana | Treccani, il portale del sapere". www.treccani.it. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ^ Bietti Sestieri 2010, p. 31.

- ^ Delia Guasco 2006, p. 118.

- ^ Delia Guasco 2006, p. 66-67.

- ^ Delia Guasco 2006, p. 69.

- ^ Piccolo, Salvatore. "The Dolmens of Sicily". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ^ "Siculi nell'Enciclopedia Treccani". www.treccani.it. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ^ "SICILIA in "Enciclopedia Italiana"". www.treccani.it. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ^ Facies culturale di Palma Campania(in Italian)

- ^ Bietti Sestieri 2010, p. 128.

- ^ a b c Cardarelli, Andrea. "The Collapse of the Terramare Culture and growth of new economic and social System during the late Bronze Age in Italy". Retrieved 14 March 2023 – via www.academia.edu.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Bietti Sestieri 2010, p. 78.

- ^ Bietti Sestieri 2010, p. 60.

- ^ Venceslas Kruta: La grande storia dei celti. La nascita, l'affermazione e la decadenza, Newton & Compton, 2003, ISBN 88-8289-851-2, ISBN 978-88-8289-851-9

- ^ Di Maio, 1998.

- ^ Treccani, Protovillanoviano

- ^ J.P.Mallory, D.Q. Adams - "Encyclopedia of Indo-European culture" pg.183-184 "Este culture".

- ^ Bartoloni, Gilda (2012). La cultura villanoviana (in Italian). Carocci. pp. 79–101. ISBN 978-8843063437.

- ^ Turfa, Jean MacIntosh (2013). The Etruscan World. Routledge. pp. 223–225. ISBN 978-0415673082.

- ^ Pallottino, Massimo (1991). A History of Earliest Italy. University of Michigan Press. pp. 77–85. ISBN 978-0472101092.

- ^ Bonfante, Larissa (2006). Etruscan Dress. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 9–14. ISBN 978-0801887093.

- ^ Haynes, Sybille (2000). Etruscan Civilization: A Cultural History. British Museum Press. pp. 121–139. ISBN 978-0714122755.

- ^ Stoddart, Simon (2020). Power and Place in Etruria: The Spatial Dynamics of a Mediterranean Civilization, 1200–500 BC. Cambridge University Press. pp. 23–45. ISBN 978-1108481755.

- ^ Izzet, Vedia (2007). The Archaeology of Etruscan Society. Cambridge University Press. pp. 143–189. ISBN 978-0521858779.

- ^ Guzzo, Pier Giovanni (2016). Le città di Magna Grecia e di Sicilia dal VI al I secolo (in Italian). Istituto Poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato. pp. 45–78. ISBN 978-8824045568.

- ^ Malkin, Irad (2011). A Small Greek World: Networks in the Ancient Mediterranean. Oxford University Press. pp. 119–155. ISBN 978-0199734818.

- ^ De Angelis, Franco (2016). Archaic and Classical Greek Sicily: A Social and Economic History. Oxford University Press. pp. 221–266. ISBN 978-0195170474.

- ^ Boardman, John (2001). The Oxford History of Greece and the Hellenistic World. Oxford University Press. pp. 175–194. ISBN 978-0192801371.

- ^ Osborne, Robin (2009). Greece in the Making 1200–479 BC. Routledge. pp. 110–134. ISBN 978-0415469920.

- ^ Aubet, María Eugenia (2001). The Phoenicians and the West: Politics, Colonies and Trade. Cambridge University Press. pp. 215–233. ISBN 978-0521795432.

- ^ Cornell, Tim J. (1995). The Beginnings of Rome: Italy and Rome from the Bronze Age to the Punic Wars (c. 1000–264 BC). Routledge. pp. 31–57. ISBN 978-0415015967.

- ^ Forsythe, Gary (2005). A Critical History of Early Rome: From Prehistory to the First Punic War. University of California Press. pp. 93–110. ISBN 978-0520226517.

- ^ Salmon, E.T. (1967). Samnium and the Samnites. Cambridge University Press. pp. 26–44. ISBN 978-0521061858.

- ^ Guasco, Delia (2006). Antica Italia: Alle origini della nostra identità (in Italian). Sartorio Publications. p. 64.

- ^ Williams, J.H.C. (2001). Beyond the Rubicon: Romans and Gauls in Republican Italy. Oxford University Press. pp. 83–107. ISBN 978-0198153009.

- ^ Terrenato, Nicola (2019). The Early Roman Expansion into Italy: Elite Negotiation and Family Agendas. Cambridge University Press. pp. 53–78. ISBN 978-1108472821.

Sources

- Armstrong, Jeremy; Rhodes-Schroder, Aaron (2023). Adoption, adaptation, and innovation in pre-Roman Italy: paradigms for cultural change. Turnhout: Brepols. ISBN 9782503602325.

- Anati, Emmanuel (1964). La civiltà di Val Camonica. Milan: Il Saggiatore (casa editrice).

- Buti, G. Gianna-Devoto, Giacomo (1974), Preistoria e storia delle regioni d'Italia, Sansoni Università.

- Bietti Sestieri, Anna Maria (2010). L'Italia nell'età del bronzo e del ferro: dalle palafitte a Romolo (2200-700 a.C.) (in Italian). Carocci. ISBN 978-88-430-5207-3.

- Guasco, Delia (2006). Popoli italici: l'Italia prima di Roma (in Italian). Giunti. ISBN 978-88-09-04062-5.

- Peroni, Renato (2004). L'Italia alle soglie della Storia, Editori Laterza, ISBN 9788842072409.

- Piccolo, Salvatore (2013). Ancient Stones: The Prehistoric Dolmens of Sicily. Abingdon/GB, Brazen Head Publishing, ISBN 9780956510624.