Preah Khan

| Preah Khan | |

|---|---|

| |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Hinduism |

| Deity | Vishnu |

| Location | |

| Location | Angkor |

| Country | Cambodia |

| Geographic coordinates | 13°27′43″N 103°52′18″E / 13.4619594°N 103.8715911°E |

| Architecture | |

| Type | Khmer |

| Creator | Jayavarman VII |

| Completed | 1191 A.D. |

| Website | |

| wmf.org/preah-khan | |

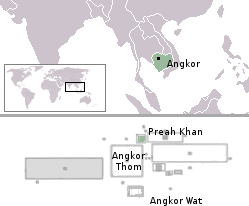

Preah Khan (Khmer: ប្រាសាទព្រះខ័ន; "Royal Sword") is a temple at Angkor, Cambodia, built in the 12th century for King Jayavarman VII to honor his father.[1]: 383–384, 389 [2]: 174–176 It is located northeast of Angkor Thom and just west of the Jayatataka baray, with which it was associated. It was the centre of a substantial organisation, with almost 100,000 officials and servants. The temple is flat in design, with a basic plan of successive rectangular galleries around a Buddhist sanctuary complicated by Hindu satellite temples and numerous later additions. Like the nearby Ta Prohm, Preah Khan has been left largely unrestored, with numerous trees and other vegetation growing among the ruins.

History

Preah Khan was built on the site of Jayavarman VII's victory over the invading Chams in 1191 [citation needed]. Unusually the modern name, meaning "holy sword", is derived from the meaning of the original—Nagara Jayasri (holy city of victory).[1] The site may previously have been occupied by the royal palaces of Yasovarman II and Tribhuvanadityavarman.[2] The temple's foundation stela has provided considerable information about the history and administration of the site: the main image, of the bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara in the form of the king's father, was dedicated in 1191 (the king's mother had earlier been commemorated in the same way at Ta Prohm). 430 other deities also had shrines on the site, each of which received an allotment of food, clothing, perfume and even mosquito nets;[3] the wealth and treasure of this ruin includes gold, silver, gems, 112,300 pearls and a cow with gilded horns.[4] The institution combined the roles of city, temple and Buddhist university: there were 97,840 attendants and servants, including 1000 dancers[5] and 1000 teachers.[6]

Preah Khan experienced a slow decline because the Khmer royalty stopped supporting it around the 15th century.[3] As support from the royal family dwindled, it became difficult to maintain and use the complex. Despite this decline, certain sections of the site continued to be used for religious or cultural activities.

The temple is still largely unrestored: the initial clearing was from 1927 to 1932, and partial anastylosis was carried out in 1939. Since then free-standing statues have been removed for safe-keeping, and there has been further consolidation and restoration work. Throughout, the conservators have attempted to balance restoration and maintenance of the wild condition in which the temple was discovered: one of them, Maurice Glaize, wrote that;

The temple was previously overrun with a particularly voracious vegetation and quite ruined, presenting only chaos. Clearing works were undertaken with a constant respect for the large trees which give the composition a pleasing presentation without constituting any immediate danger. At the same time, some partial anastylosis has revived various buildings found in a sufficient state of preservation and presenting some special interest in their architecture or decoration.[7]

Since 1991, the site has been maintained by the World Monuments Fund. It has continued the cautious approach to restoration, believing that to go further would involve too much guesswork, and prefers to respect the ruined nature of the temple. One of its former employees has said, "We're basically running a glorified maintenance program. We're not prepared to falsify history".[8] It has therefore limited itself primarily to stabilisation work on the fourth eastern gopura, the House of Fire and the Hall of Dancers.[9]

The site

The outer wall of Preah Khan is of laterite, and bears 72 garudas holding nagas, at 50 m intervals. Surrounded by a moat, it measures 800 by 700 m and encloses an area of 56 hectares (140 acres). To the east of Preah Khan is a landing stage on the edge of the Jayatataka baray, which measures 3.5 by 0.9 km (2 by 1 mi). This also allowed access to the temple of Neak Pean in the centre of the baray. Once dried up, the Jayatataka baray is now filled with water again, as at the end of each rainy season, all excess water in the area is diverted into it.[4]

As usual Preah Khan is oriented toward the east, so this was the main entrance, but there are others at each of the cardinal points. Each entrance has a causeway over the moat with nāga-carrying devas and asuras similar to those at Angkor Thom; Glaize considered this an indication that the city element of Preah Khan was more significant than those of Ta Prohm or Banteay Kdei.[10]

Halfway along the path leading to the third enclosure, on the north side, is a House of Fire (or Dharmasala) similar to Ta Prohm's. The remainder of the fourth enclosure, now forested, was originally occupied by the city; as this was built of perishable materials it has not survived. The third enclosure wall is 200 by 175 metres (656 by 574 ft). In front of the third gopura is a cruciform terrace. The gopura itself is on a large scale, with three towers in the centre and two flanking pavilions. Between the southern two towers were two celebrated silk-cotton trees, of which Glaize wrote, "resting on the vault itself of the gallery, [they] frame its openings and brace the stones in substitute for pillars in a caprice of nature that is as fantastic as it is perilous."[11] One of the trees is now dead, although the roots have been left in place. The trees may need to be removed to prevent their damaging the structure.[12] On the far side of the temple, the third western gopura has pediments of a chess game and the Battle of Lanka, and two guardian dvarapalas to the west.

West of the third eastern gopura, on the main axis is a Hall of Dancers. The walls are decorated with apsaras; Buddha images in niches above them were systematically destroyed during the reign Jayavarman VIII. North of the Hall of Dancers is a two-storeyed structure with round columns. No other examples of this form survive at Angkor, although there are traces of similar buildings at Ta Prohm and Banteay Kdei. Freeman and Jacques speculate that this may have been a granary.[13] Occupying the rest of the third enclosure are ponds (now dry) in each corner, and satellite temples to the north, south and west. While the main temple was Buddhist, these three are dedicated to Shiva, previous kings and queens, and Vishnu respectively. They are notable chiefly for their pediments: on the northern temple, Vishnu reclining to the west and the Hindu trinity of Vishnu, Shiva and Brahma to the east; on the western temple, Krishna raising Mount Govardhana to the west.[14]

Connecting the Hall of Dancers and the wall of the second enclosure is a courtyard containing two libraries. The second eastern gopura projects into this courtyard; it is one of the few Angkorian gopuras with significant internal decoration, with garudas on the corners of the cornices. Buddha images on the columns were changed into hermits under Jayavarman VIII.

Between the second enclosure wall (85 by 76 m or 279 by 249 ft) and the first enclosure wall (62 by 55 m or 203 by 180 ft) on the eastern side is a row of later additions which impede access and hide some of the original decoration. The first enclosure is, as Glaize said, similarly, "choked with more or less ruined buildings".[15] The enclosure is divided into four parts by a cruciform gallery, each part almost filled by these later irregular additions. The walls of this gallery, and the interior of the central sanctuary, are covered with holes for the fixing of bronze plates which would originally have covered them and the outside of the sanctuary—1500 tonnes was used to decorate the whole temple.[16] At the centre of the temple, in place of the original statue of Lokesvara, is a stupa built several centuries after the temple's initial construction.

Microbial degradation

Microbial biofilms have been found degrading sandstone at Angkor Wat, Preah Khan, and the Bayon and West Prasat in Angkor. The dehydration and radiation resistant filamentous cyanobacteria can produce organic acids that degrade the stone. A dark filamentous fungus was found in internal and external Preah Khan samples, while the alga Trentepohlia was found only in samples taken from external, pink-stained stone at Preah Khan.[5]

Photo gallery

- Moat that surrounds the temple complex

- Sculptures on the way to the temple

- Bridge

- Library

- Gopura

- One-story structure at Preah Khan

- Entrance

- Interior of the temple

- Carved lintel

- Jayadevi, one of Jayavarman VII's two sister-wives

- Balustered windows

- Pediment depicting the Battle of Lanka

- Jayatataka Baray

Notes

- ^ Glaize, The Monuments of the Angkor Group p. 173 quoting Coedès.

- ^ Freeman and Jacques, Ancient Angkor p. 170.

- ^ Higham, The Civilization of Angkor p. 128.

- ^ Higham p. 129.

- ^ Glaize p. 175.

- ^ Freeman and Jacques p. 170.

- ^ Glaize p. 175.

- ^ John Sanday, quoted by Denis D. Gray in Nations' trials meant to prevent errors during restoration of Angkor

- ^ World Monuments Fund, World Monuments Fund at Angkor

- ^ Glaize p. 173.

- ^ Glaize p. 177.

- ^ Gunther, Preah Khan

- ^ Freeman and Jacques p. 174.

- ^ Glaize p. 179.

- ^ Glaize p. 178.

- ^ Freeman and Jacques p. 176.

References

- ^ Higham, C., 2014, Early Mainland Southeast Asia, Bangkok: River Books Co., Ltd., ISBN 9786167339443

- ^ Coedès, George (1968). Walter F. Vella (ed.). The Indianized States of Southeast Asia. trans.Susan Brown Cowing. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-0368-1.

- ^ "Preah Khan Conservation Project Report V" (PDF). World Monuments Fund. July 1994.

- ^ "Preah Khan". Siemreap.net. 2017. Retrieved 29 April 2017.

- ^ Gaylarde CC; Rodríguez CH; Navarro-Noya YE; Ortega-Morales BO (Feb 2012). "Microbial biofilms on the sandstone monuments of the Angkor Wat Complex, Cambodia". Current Microbiology. 64 (2): 85–92. doi:10.1007/s00284-011-0034-y. PMID 22006074. S2CID 14062354.

- Freeman, Michael and Jacques, Claude (1999). Ancient Angkor. River Books. ISBN 0-8348-0426-3.

- Glaize, Maurice (2003 edition of an English translation of the 1993 French fourth edition). The Monuments of the Angkor Group. Retrieved 14 July 2005.

- Gray, Denis D. (January 15, 1998). Nations' trials meant to prevent errors during restoration of Angkor. Accessed 22 August 2005.

- Gunther, Michael D. (1994). Art of Southeast Asia Accessed 22 August 2005.

- Higham, Charles (2001). The Civilization of Angkor. Phoenix. ISBN 1-84212-584-2.

- Jessup, Helen Ibbitson; Brukoff, Barry (2011). Temples of Cambodia - The Heart of Angkor (Hardback). Bangkok: River Books. ISBN 978-616-7339-10-8.

- World Monuments Fund. World Monuments Fund at Angkor Accessed 22 August 2005.

External links

Geographic data related to Preah Khan at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to Preah Khan at OpenStreetMap

- The Monuments of the Angkor Group by Maurice Glaize, online version

- General Views of Preah Khan

- Preah Khan - Khmer Goddesses in the Heart of the Temple