Pottery Lane

| Pottery lane | |

|---|---|

Beehive kiln on Walmer Road, just north of Pottery Lane | |

| OS grid reference | TQ2480 |

| Ceremonial county | Greater London |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | LONDON |

| Postcode district | W11 |

| Dialling code | 020 |

| Police | Metropolitan |

| Fire | London |

| Ambulance | London |

| UK Parliament | |

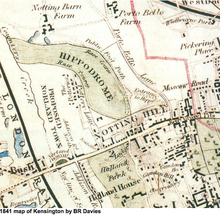

Pottery Lane is a street in Notting Hill, west London. Today it forms part of one of London's most fashionable and expensive neighbourhoods, but in the mid-19th century it lay at the heart of a wretched and notorious slum known as the "Potteries and the Piggeries". The slum came to the attention of Londoners with the building of the Hippodrome in 1837 by entrepreneur John Whyte. Unfortunately for Whyte a public right of way existed over his land and "dirty and dissolute vagabonds" from the nearby slum invaded his racecourse, adding to his financial difficulties and, in part, leading to the closure of his venture in 1842. Pottery Lane gradually improved in the late 20th century along with the rest of the Notting Hill area, and today the houses there fetch multi-million pound prices. Just one of the original brick kilns still survives; it is located in Walmer Road, just north of Pottery Lane, and bears a commemorative plaque placed there by the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea.

History

Pottery Lane takes its name from the brickfields which lay at the northern end of the street. According to the Victorian author and philanthropist Mary Bayly, the local soil was "almost entirely composed of stiff clay, peculiarly adapted for that purpose [brick making]",[1] and from the late 18th century, high-quality clay was dug here and used for brick making to supply the voracious appetite of London's growing suburbs. Bricks and tiles were stored in sheds lining Pottery Lane and were fired in large kilns – one of which, on Walmer Road, remains to this day.[2]

During the 19th century the fields around London were built up with new housing. Commonly, a field would be excavated to expose the brickearth or London clay subsoil, which was then turned into bricks on the site by moulding and firing them. The bricks would then be used to build houses adjacent to the brickfield as transport was expensive. Once the building work was nearing completion, the brickfield would be levelled and built upon while a new brickfield further out would supply the bricks.[3]

Potteries and Piggeries

The Pottery Lane brick makers soon found themselves living and working with pig-keepers who had been forced to move west from Marble Arch and Tottenham Court Road as London expanded westwards.[4] Sanitation was poor and fresh water scarce. Many families lived with the pigs in their hovels, which soon became slums. The brick-makers themselves were said to be "notorious types", known for "riotous living".[5]

One local resident, who had lived in the neighbourhood for forty years, described the area to Mary Bayly:

- "Now pig keepers is respectable; but them bricklayers, they bean't, some of them, no wiser than the clay theys works on....On Sundays we had cock-fighting and bull-baiting, and lots of dogs were kept on purpose to amuse the people by fighting and rat killing. People around the place were frightened of these dogs, and nobody ever cared to come nigh the place. We didn't ourselves venture out after it was dark; if we hadn't got in all we wanted before night, why we jist went without it, for besides the dogs...there was the roads; leastwise, we called 'em roads, but they wornt for all that - it was jist a lot of ups and downs, and when you had put one foot down, you didn't know how to pull the other one up."[6]

There were no planning restrictions and no proper drainage or sanitary arrangements. Extraction of the clay left large holes which became filled with stagnant water, pig slurry and sewage. One of these pools grew to such proportions that it became known as "the Ocean".[7] In the mid-19th century the street had become so bad it became known as "Cut throat lane". In 1850 Charles Dickens described the area as "a plague spot scarcely equalled for its insalubrity by any other in London".

The Hippodrome

Dickens' criticism was unusual, as very few Londoners ventured anywhere near the Potteries and Piggeries. It was only with the building of the Hippodrome in 1837 by entrepreneur John Whyte, that the squalor of Pottery Lane was brought to London's attention. Whyte leased 140 acres (0.57 km2) of land from James Weller Ladbroke, owner of the Ladbroke Estate,[8] and proceeded to enclose "the slopes of Notting Hill and the meadows west of Westbourne Grove" with a 7-foot (2.1 m) high wooden paling, creating a racecourse intended to rival Epsom and Ascot. Unfortunately, the racecourse bordered on Pottery Lane and a public right of way existed over Whyte's land, making the race meetings easily accessible by the local slum-dwellers. These were not the sort of customers that Whyte had in mind, and The Times's correspondent complained of "the dirty and dissolute vagabonds of London, a more filthy and disgusting crew ...we have seldom had the misfortune to encounter." Whyte was unable to eject these less than appealing visitors, whose "villainous activities" were a continual source of trouble,[8] and the Hippodrome was finally closed in 1842.

Pottery Lane today

Today the houses in Pottery Lane sell for seven-figure sums. Just one of the original brick kilns still survives; it is located in Walmer Road, just north of Pottery Lane, and bears a commemorative plaque placed there by the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. "The Ocean" was filled and covered in 1892 and is now leafy Avondale Park.[9]

See also

References

- Bayly, Mary, Ragged homes, And How To Mend Them, London (1859). Retrieved 2 February 2010

- Denny, Barbara, Notting Hill and Holland Park Past, Historical Publications (1993). ISBN 0-948667-18-4

- Whetlor, Shaaron, Story of Notting Dale: From Potteries and Piggeries to Present Times, Kensington & Chelsea Community History Group (1998), ISBN 978-1-873094-07-5

- Wormell, Mary Jo, The Hippodrome Race-course Fiasco, published in News from Ladbroke, newsletter of the Ladbroke Association, (Summer 1995).

Notes

- ^ Bayly, Mary, p.24, Ragged homes, And How To Mend Them, London (1859). Retrieved 2 February 2010

- ^ Denny, p84

- ^ www.brickfields.org.uk Retrieved February 2012

- ^ Hardman, Josh (18 August 2018). "Community Responses to Infrastructure Projects in Notting Dale". London Geographies.

- ^ Whetlor

- ^ Bayly, Mary, p.25, Ragged homes, And How To Mend Them, London (1859). Retrieved 2 February 2010

- ^ Duncan, Andrew, p.47, Andrew Duncan's Favourite London Walks. Retrieved 2 February 2010

- ^ a b Wormell

- ^ Short piece on Pottery Lane at www.britishlocalhistory.co.uk Retrieved 24 April 2010

External links

- Article by Ian Youngs at BBC news Online, 17 May 2004, Streets of London: Pottery Lane. Retrieved 2 February 2010

- Potteries and piggeries and the history of Notting Dale at www.worley.org.uk Retrieved 2 February 2010

- Short piece on Pottery Lane at www.britishlocalhistory.co.uk Retrieved 2 February 2010

- Kensington & Chelsea Community History Group Retrieved May 2012