Porsche in motorsport

Porsche has been successful in many branches of motorsport of which most have been in long-distance races.

Despite their early involvement in motorsports being limited to supplying relatively small engines to racing underdogs up until the late 1960s, by the mid-1950s Porsche had already tasted moderate success in the realm of sports car racing, most notably in the Carrera Panamericana and Targa Florio, classic races which were later used in the naming of streetcars.[citation needed] The Porsche 917 of 1969 turned them into a powerhouse, winning in 1970 the first of over a dozen 24 Hours of Le Mans, more than any other company. With the 911 Carrera RSR and the Porsche 935 Turbo, Porsche dominated the 1970s and even has beaten sports prototypes, a category in which Porsche entered the successful 936, 956, and 962 models.

Porsche is currently the world's largest race car manufacturer. In 2006, Porsche built 195 race cars for various international motor sports events, and in 2007 Porsche is expected to construct no fewer than 275 dedicated race cars (7 RS Spyder LMP2 prototypes, 37 GT2 spec 911 GT3-RSRs, and 231 911 GT3 Cup vehicles).[1]

Porsche regards racing as an essential part of ongoing engineering development—it was traditionally very rare for factory-entered Porsche racing cars to appear at consecutive races in the same specification. Some aspect of the car almost invariably was being developed, whether for the future race programs or as proof of concept for future road cars.

Early years

As Porsche only had small capacity road and racing cars in the 1950s and 1960s, they scored many wins in their classes, and occasionally also overall victories against bigger cars, most notably winning the Targa Florio in 1956, 1959, 1960, 1964, and every year from 1966 to 1970 in prototypes that lacked horsepower relative to the competition, but which made up for that, with reliability, low drag, low weight and good handling.[citation needed]

In their September 2003 publication, Excellence magazine identified Lake Underwood as Porsche's quiet giant in the United States[2] and he is among the four drivers, including Art Bunker, Bob Holbert, and Charlie Wallace who are identified by the Porsche Club of America as having made Porsche a giant-killer in the US during the 1950s and early 1960s.[3] Notable early successes in the US also included an overall win in the 1963 Road America 500 in an Elva Mark 7 Porsche powered sports racer driven by Bill Wuesthoff and Augie Pabst.

Porsche started racing with lightweight, tuned derivatives of the 356 road car, but rapidly moved on to campaigning dedicated racing cars, with the 550, 718, RS, and RSK models being the backbone of the company's racing programme through to the mid-1960s. The 90x series of cars in the 60s saw Porsche start to expand from class winners that stood a chance of overall wins in tougher races where endurance and handling mattered, to likely overall victors. Engines did not surpass the two litres mark until the rule-makers limited the capacity of the prototype class to 3 litres after 1967, as the four-litre Ferrari P series and the seven-litre Ford GT40 became too fast. Porsche first expanded its 8-cyl flat engine to 2.2 litres in the 907, then developed the 908 with full three litres in 1968. Based on this 8-cyl flat engine and a loophole in the rules, the 4.5-litre flat 12 917 was introduced in 1969, eventually expanded to five litres, and later even to 5.4 and turbocharged. Within a few years, Porsche with the 917 had grown from underdog to the supplier of the fastest (380 km/h at Le Mans) and most powerful (1580 hp in CanAm) race car in the world.[citation needed]

Five decades of Porsche 911 success

Even though introduced in 1963, and winning the Rally Monte Carlo, the Porsche 911 classic (built until 1989) established its reputation in production-based road racing mainly in the 1970s.

- Porsche 911 Carrera RSR, winner of the Targa Florio, Daytona and Sebring in the mid-1970s

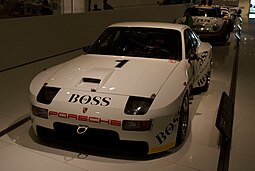

- Porsche 934

- Porsche 935, winner in Le Mans 1979

Due to regulation restraints, the 911 was not used very much in the 1980s but returned in the 1990s as the Porsche 993, like the GT2 turbo model. The water-cooled Porsche 996 series became a success in racing after the GT3 variant was introduced in 1999.

24 Hours of Le Mans successes

The Porsche 917 is considered one of the most iconic racing cars of all time and gave Porsche their first 24 Hours of Le Mans wins, while open-top versions of it dominated Can-Am racing. After dominating Group 4, 5, and 6 racing in the 1970s with the 911-based 934 and 935 customers cars and the factory-only prototype 936, Porsche moved on to dominate Group C and IMSA GTP in the 1980s with the Porsche 956/962C, one of the most prolific and successful sports prototype racers ever produced - and sold in large numbers, too.

Although the car was never intended to win outright at Le Mans the Porsche 924/944 platforms were still able to secure class wins throughout their relatively short time tenure at Le Mans. The year 1980 saw the ultimate iteration of the 924 battle it out against opponents with larger engine displacements, ultimately it was able to secure a 6th place overall finish with a 2nd in its under 3-litre GTP class. The following year, 1981 saw once again multiple entries of the 924, with one car utilising a prototype version of the upcoming 944's 2.5-litre engine. This 924 GTP (sometimes called 944 LM) was piloted by Jürgen Barth and Walter Röhrl to a class win for the new GTP+3.0 class and 7th overall, 31 laps behind the overall Porsche 936/81 winner. Its stablemate, a 924 Carrera GTR piloted by Andy Rouse and Manfred Schurti, was then driven to another class victory for the IMSA GTO class and an 11th overall position.[4][5]

While there was no longer a factory team running the 924 GTR in 1982, the car would still be fielded to another class win in the IMSA GTO class by BF Goodrich Brornos team with drivers Doc Bundy and Marcel Mignot.[4]

Porsche scored a couple of unexpected Le Mans wins in 1996 and 1997. A return to prototype racing in the US was planned for 1995 with a Tom Walkinshaw Racing chassis formerly used as the Jaguar XJR-14 and the Mazda MXR-01 fitted with a Porsche engine. IMSA rule changes struck this car out of the running and the private Joest Racing team raced the cars in Europe for two years, winning back-to-back Le Mans with the same chassis, termed the Porsche WSC-95. This is a feat Joest had also achieved in the 1980s with 956 chassis 117, contrasting with the works habit of the 1960s and later where most factory race cars ran only one or two races for the works team before being sold on to finance newer cars.

Between 1998 (when Porsche won overall with the Porsche 911 GT1-98) and 2014, Porsche did not attempt to score overall wins at Le Mans and similar sports car races, focusing on smaller classes and developing the water-cooled 996 GT3. Nevertheless, the GT3 and the LMP2 RS Spyder won major races overall during the period. Hybrid technology was tested in endirance races with the Porsche 911 GT3 R Hybrid in 2010 and 2011.

When Le Mans adopted Hybrid rules as a new challenge and stopped giving advantage to Diesel, Porsche returned to top-tier Le Mans racing in 2014 with the Porsche 919 Hybrid, but both cars experienced unknown engine issues with an hour and a half left to go and retired just as the #20 car was chasing down the #1 Audi in first place.

In 2015, a Porsche 919 Hybrid hybrid car driven by Nick Tandy, Earl Bamber and Nico Hülkenberg won the 83rd running of the 24 Hours of Le Mans. The Porsche LMP1 program went on to win the overall victory in the 2015 FIA World Endurance Championship. The 919 program has also gone on to win the 84th running of Le Mans (2016) in a 919 driven by Neel Jani, Romain Dumas, and Marc Lieb, taking the lead with just over 3 minutes left. Porsche completed a hat trick by winning the 2017 24 Hours of Le Mans with drivers Timo Bernhard, Earl Bamber, and Brendon Hartley. After the 919 had scored the 19th overall Porsche win, it was retired.

About half a year after Audi left, in mid-2017, Porsche announced that they would close their LMP1 program at the end of the year.[6] At the time, the Porsche museum guides put emphasis on the all-electric and hybrid cars developed by Ferdinand Porsche in the early 1900s, and Porsche focussed on the Porsche Mission E and Formula E racing. Porsche returned to the 24 Hours of Le Mans and the FIA World Endurance Championship in 2023 with the new Porsche 963 hybrid sports prototype.[7]

Teams and sponsorship

In the 1960s, Porsche grew into a major competitor in sports car racing, sometimes entering half a dozen cars which were soon sold to customers. Apart from the factory team, calling itself Porsche AG or Porsche System Engineering since 1961, Austrian-based Porsche Salzburg was set up in 1969 as a second works team to share the workload, providing the much sought first overall win at Le Mans, in 1970. Martini Racing and John Wyer's Gulf Racing were other teams receiving factory support, allowing Zuffenhausen to focus on development, while the teams provided the sponsorship funds and manpower to be present and successful at many international races. In CanAm, Porsche cooperated with Penske, while in Deutsche Rennsportmeisterschaft, customers like Kremer Racing, Georg Loos and Joest Racing enjoyed various degrees of factory support. After appearing as Martini Porsche in the mid-1970s, the factory entered as Rothmans Porsche in the mid-1980s.

Many Porsche race cars are run successfully by customer teams, financed, and run without any factory support; often they have beaten the factory itself.

Recently, 996-generation 911 GT3s have dominated their class at Le Mans and similar endurance and GT races. The late 1990s saw the rise of racing success for Porsche with The Racer's Group, a team owned by Kevin Buckler in Northern California. In 2002, Buckler won the 24 Hours of Daytona GT Class and the 24 Hours of Le Mans GT Class. In 2003, a 911 run by The Racers Group (TRG) became the first GT Class vehicle since 1977 to take the overall 24 Hours of Daytona victory. At the 24h Nürburgring, factory-backed Manthey Racing GT3 won since 2006. The team of Olaf Manthey, based at the Nürburgring, had entered the semi-works GT3-R in 1999.

Rally

The various versions of the Porsche 911 proved to be a serious competitor in rallies. The Porsche works team was occasionally present in rallying from the 1960s to the late 1970s. In 1967 the Polish driver Sobiesław Zasada drove a 912 to capture the European Rally Championship for Group 1 series touring cars.[8] Porsche took three double wins in a row in the Monte Carlo Rally; in 1968 with Vic Elford and Pauli Toivonen, and in 1969 and 1970 with Björn Waldegård and Gérard Larrousse. In 1970, Porsche also edged Alpine-Renault to win the International Championship for Manufacturers (IMC), the predecessor to the World Rally Championship (WRC). Porsche's first podium finish in the WRC was Leo Kinnunen's third place at the 1973 1000 Lakes Rally.

Although the Porsche factory team withdrew from the WRC with no wins to their name, the best private 911s were often close to other brands' works cars. Jack Tordoff was the first privateer to win an International Rally using a 911 2.7 Carrera RS Sport (Lightweight) on the Circuit of Ireland in 1973 (a round of the European Rally Championship). This success was followed by Cathal Curley who won the 1973 Donegal International Rally in a 911 2.7 RS Touring. Cathal Curley followed this with the greatest run of International Rally wins ever recorded in a Porsche Carrera RS when in 1974 he won the Circuit of Ireland, Donegal and Manx International Rallies in AUI 1500, the last Rhd 911 2.7 Carrera RS Sport produced by Porsche. In 1975 Cathal Curley upgraded to the new 3.0 Carrera RS in 1975 and won the Cork 20 which became an International Rally in 1977. Cathal Curley won four International Rallies in a 2.7 Carrera RS, multiple wins in mechanically standard cars straight off the showroom floor. These wins were all the more impressive as Ireland was the hotbed of International Rallying for the Porsche 911 RS in the 1970s. Jack Tordoff's victory was steady and deserved as he stalked the leading works backed Escort that failed on the penultimate stage beating this car and two other entered 911s but by 1974 Cathal Curley's wins came against no less than fourteen other 911 RSs beating the great Roger Clark in a works backed Escort in the 1974 Manx International Rally too. Over half of the UK allocation of 17 2.7 RS Sport (Lightweights) were rallied at any one time in Ireland in the 1970s.

Jean-Pierre Nicolas managed to win the 1978 Monte Carlo Rally with a private 911 SC, and Porsche's second, and so far last, WRC win came at the 1980 Tour de Corse in the hands of Jean-Luc Thérier. In the European Rally Championship, the 911 was driven to five titles, and as late as 1984, Henri Toivonen took his Prodrive-built and Rothmans-sponsored 911 SC RS to second place behind Carlo Capone and the Lancia Rally 037. In 1984 and 1986, the Porsche factory team won the Paris Dakar Rally, also using the 911 derived Porsche 959 Group B supercar.

Porsche won the Spanish Rally Championship five times between 2009 and 2015 with Sergio Vallejo and Miguel Ángel Fuster with a Porsche 911 GT3. The manufacturer also won the 2015 and 2017 FIA R-GT Cup with François Delecour and Romain Dumas respectively, also with a 911 GT3.

IMC results

| Year | Car | Driver | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | IMC | Points |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1970 | Porsche 911 S | MON 1 |

SWE 1 |

ITA | KEN | AUT 1 |

GRE Ret |

GBR Ret |

1st | 28 | |||

| MON 2 |

SWE | ITA | KEN | AUT | GRE | GBR 6 |

|||||||

| MON 4 |

SWE Ret |

ITA | KEN | AUT Ret |

GRE Ret |

GBR Ret |

|||||||

| MON | SWE 5 |

ITA | KEN | AUT | GRE | GBR | |||||||

| 1971 | Porsche 914/6 | MON 3 |

3rd | 16.5 | |||||||||

| Porsche 911 S | SWE 4 |

ITA | KEN Ret |

MAR | AUT | GRE | GBR 2 |

||||||

| Porsche 914/6 | MON Ret |

||||||||||||

| Porsche 911 S | SWE 6 |

ITA | KEN Ret |

MAR | AUT | GRE | GBR |

Formula One

Despite Ferdinand Porsche having designed Grand Prix cars in the 1920s and 1930s for Mercedes and Auto Union, the Porsche AG never felt at home in single-seater series.

In the late 1950s the Porsche 718 RSK, a two-seater sports car, was entered in Formula Two races, as rules permitted this, and lap times were promising. The 718 was first modified by moving the seat into the center of the car, and subsequently proper open wheelers were built. These 1500 cc cars enjoyed some success. The former F2 cars were moved up to Formula One in 1961, where Porsche's outdated design was not competitive. For 1962, a newly developed flat-eight powered and sleek Porsche 804 produced Porsche's only win as a constructor in a championship race, claimed by Dan Gurney at the 1962 French Grand Prix. One week later, he repeated the success in front of Porsche's home crowd on Stuttgart's Solitude in a non-championship race. At the end of the season, Porsche withdrew from F1 due to the high costs,[citation needed] just having acquired the Reutter factory. Volkswagen and German branches of suppliers had no interest in an F1 commitment as this series was too far away from road cars. Privateers continued to enter the outdated Porsche 718 in F1 until 1964.

Having been very successful with turbocharged cars in the 1970s, Porsche returned to Formula One in 1983 after nearly two decades away, supplying water-cooled V6 turbo engines badged as TAG units for the McLaren team, as the partner electronics firm was paying for the whole engine program, with the deal they would be badged as TAG units. For aerodynamic reasons, the Porsche-typical flat engine was out of the question for being too wide. With turbo power being the way to go in F1 at the time a 90° V6 turbo engine was produced. The TAG engine was designed to very tight requirements issued by McLaren's chief designer John Barnard. He specified the physical layout of the engine to match the design of his proposed car. The engine was funded by TAG who retained the naming rights to it, although the engines bore "made by Porsche" identification. Initially, Porsche was reluctant to have their name on the engines, fearing bad publicity if they failed. However, within a few races of the 1984 season when it became evident that the engines were the ones to have, the "Made by Porsche" badges began to appear. TAG-Porsche-powered cars took two constructor championships in 1984 and 1985, and three driver crowns in 1984, 1985 and 1986. The engines powered McLaren to 25 victories between 1984 and 1987, with 19 for 1985 and 1986 World Champion Alain Prost, and 6 for 1984 Champion Niki Lauda.

Despite its overwhelming success, the TAG-Porsche engines were never the most powerful in Formula One as they did not have the ability to hold higher turbo boost like the rival BMW, Renault, Ferrari and Honda engines. The McLaren drivers who regularly raced with the engine (Lauda, Prost, Keke Rosberg and Stefan Johansson) continually asked Porsche to develop a special qualifying engine like their rivals. However, both Porsche and TAG owner Mansour Ojjeh balked at the requests due to the extra costs involved, reasoning that the proven race engines already had equal power and better fuel economy than all bar the Hondas, thus qualifying engines were never built. Though the lack of horsepower did not stop McLaren from claiming 7 pole positions (6 for Prost, 1 for Rosberg) and 21 front-row starts.

Porsche returned to F1 again in 1991 as an engine supplier, however, this time with disastrous results: The Footwork Arrows cars powered with the overweight Porsche 3512 double-V6 which weighed 400 pounds (180 kg), (according to various reports, including from McLaren designer Alan Jenkins, the engine was in fact 2 combined TAG V6 engines used by McLaren from 1983 to 1987 minus the turbochargers)[9] failed to score a single point, and failed even to qualify for over half the races that year. After the Porsche engines were sacked by Footwork in favor of Cosworth DFRs, Porsche has not participated in Formula One since. According to reports from Arrows, the 3512's major problem, other than a lack of horsepower, was severe oil starvation problems which often led to engine failure.

During the 2010 Paris Motor Show, Porsche chairman Matthias Mueller made a statement hinting at a possible Porsche return to Formula 1. Specifically, Mueller stated that either Porsche or Audi would compete in Le Mans while the other would turn to Formula 1. Previously, Audi's motorsport boss Wolfgang Ulrich had already stated that Audi and Formula 1 "do not fit".[10]

On 2 May 2022, Volkswagen Group's CEO Herbert Diess announced that Porsche would make their return to the sport alongside VW brand Audi. This will be Audi's first entry into the sport.[11] On 27 July in Morocco, official information was published on the approval of an application submitted jointly by Porsche and Red Bull GmbH in which Porsche acquired 50% of the shares of the Red Bull program in Formula 1. This application had to be filed with the antitrust authorities of up to 20 countries, including outside the European Union. The press release was due to go out for the Austrian GP. However, the FIA did not approve the regulations for the 2026 engines before 29 June as planned, delaying official confirmation of Porsche's entry into Formula One.[12] On 15 August, Porsche registered the "F1nally" trademark with the German Patent Office, which covers the development of different activities such as cultural and sports activities, technological and scientific services, industrial development, analysis and design, as well as the development and design of computer hardware and software, marketing and office functions, telecommunications and administration.[13]

After months of speculation, Porsche AG confirmed in September that talks with Red Bull GmbH would not continue. The intention was to reach an engine and team partnership, based on equal footing but the negotiations never came to fruition.[14] In March 2023, Porsche announced that they will not be joining Formula 1 in 2026.[15]

Formula One results

Indycar

Porsche first attempted to compete in the 1980 Indianapolis 500 with an engine initially based on the 935 sports car flat 6 with Interscope Racing as the entrant and Danny Ongais as driver. The engine would be fitted to Interscopes's new Interscope IR01, which featured a tubular rear subframe, as the Porsche motor could not be used as a stressed member as the Cosworth engines were. USAC had more favorable rules for stock-block engines at the Indy 500 than CART allowed at their races. Porsche applied to and received approval from USAC for their engine to be allowed the stock block boost pressure of 55 inches. After setting an unofficial lap record in private testing at the now-defunct Ontario Motor Speedway, a clone of the Indiana track, rumors circulated regarding the performance of the engine and top-level teams pressured officials to alter their initial ruling and now categorize the Porsche a race motor, dropping boost pressure to 48" thus losing its boost and horsepower advantage. Porsche withdrew and Interscope entered a Parnelli VPJ6C-Cosworth DFX at Indianapolis that year. The Indianapolis engine became the basis of the highly-successful 956/962 motor.

Porsche returned to CART in its 1987 season fielding Al Unser in the #6 Quaker State Porsche, with the chassis and engine both being Porsche only competing at the Champion Spark Plug 300K at Laguna Seca Raceway. Unser would qualify 21st out of 24 cars and would retire in 24th place after only seven laps due to a water pump failure. For 1988 Teo Fabi would drive the #8 Quaker State March 88C-Porsche getting a best finish of 4th at the Bosch Spark Plugs Grand Prix at Pennsylvania International Raceway, Fabi would finish tenth in points. For 1989 Fabi would drive the #8 Quaker State March 89P-Porsche qualifying on the pole position at both the Budweiser / G.I. Joe's 200 at Portland International Raceway and the Red Roof Inns 200 at Mid-Ohio Sports Car Course getting the win at the latter. Fabi would also give Porsche their best finish on an IndyCar oval by finishing 2nd at the Marlboro 500 at Michigan International Speedway.

In 1990 Porsche attempted to race a new car with carbon-fiber chassis, but CART banned it.[16] The team expanded to two cars, fielding Fabi in the #4 Foster's/Quaker State March 90P-Porsche and John Andretti in the #41 Foster's March 90P-Porsche. Fabi would qualify on the pole position at the Texaco/Havoline Grand Prix of Denver at the Streets of Denver and would finish 3rd at the Marlboro Grand Prix at the Meadowlands at the Meadowlands Sports Complex but would drop to 14th in points. While Andretti would get a best finish of 5th at the Budweiser Grand Prix of Cleveland at Burke Lakefront Airport and at the Molson Indy Vancouver at the Streets of Vancouver and would finish tenth in points.

Porsche withdrew from IndyCar at the end of the 1990 season. Team director Derrick Walker bought the assets to become the owner of Walker Racing.

Carrera Cup and amateur racing

Porsche has always been a popular marque for amateur racing GT and Production Sports Car racing in Europe, America, and Asia, particularly the Porsche 911. Stock and lightly modified Porsches are raced in many competitions around the world; many of these are primarily amateur classes for enthusiasts.

Porsche has and continues to build models based on road cars but optimised for competition, most famously the Porsche 911 GT3 Cup. Porsche has established and supported several motor racing series, many of them single-model series for Porsches, or specific models of Porsche. Porsche Carrera Cup has featured in several countries and today variations of Carrera Cup have been held in Asia, Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Britain, Italy, Japan, the Middle East, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Scandinavia as well as originating IROC in the United States. A professional series evolved from these, the European-based Porsche Supercup.

21st century

Porsche dropped its factory motorsports program after winning the 1998 24 Hours of Le Mans with the Porsche 911 GT1 for financial reasons, facing factory competition from Audi, BMW, Mercedes-Benz, Toyota, and others. An LMP1 prototype with a V10 engine, intended to be entered in 2000, was abandoned unraced due to an agreement with Audi, a related company led by Porsche co-owner Ferdinand Piech. The V10 was used in the Porsche Carrera GT instead, while Audi dominated Le Mans after BMW, Mercedes and Toyota moved to F1.

Porsche made a comeback in the LMP2 category in 2005 with the new RS Spyder prototype, although this was run by closely associated customer teams rather than by the works. This was not welcomed very much, as rule-makers intended the LMP1 category for factory entries, with the LMP2 reserved for privateers. Based on LMP2 regulations, the RS Spyder made its debut for Roger Penske's team at Mazda Raceway Laguna Seca during the final race of the 2005 American Le Mans Series season, and immediately garnered a class win in the LMP2 class finishing 5th overall. The nimble albeit less powerful (due to the regulations) RS Spyder clearly possessed the pace to challenge Audi and Lola LMP1 cars in the ALMS. Penske Racing won the LMP2 championship on its first full season in 2006 and against Acura in 2007 and 2008. 2007 was the most successful year for the RS Spyder, winning 8 overall races and 11 class wins while the Audi R10 from the larger LMP1 class won only 4 overall victories. The car debuted on European circuits in 2008 and dominated the Le Mans Series; Van Merksteijn Motorsport, Team Essex, and Horag Racing taking the first three places in the LMP2 championship. Van Merksteijn Motorsport took a class victory at the 2008 24 Hours of Le Mans and Team Essex won the LMP2 class at the 2009 24 Hours of Le Mans.

The Daytona Prototype Action Express Racing Riley-Porsche won the 2010 24 Hours of Daytona. This was unusual since the Riley-Porsche was powered by a Porsche Cayenne SUV-based 5.0-litre V8. Porsche refused to develop the V8 for the Grand-Am competition and was, instead, built by the Texas-based Lozano Brothers. Since it was not officially sanctioned by Porsche, the company did not technically claim the win.[17]

Factory drivers

Current

Former

Al Holbert

Al Holbert Andy Rouse

Andy Rouse Ben Pon

Ben Pon Björn Waldegård[21]

Björn Waldegård[21] Bob Wollek[22]

Bob Wollek[22] Brian Redman

Brian Redman Brendon Hartley

Brendon Hartley Carel Godin de Beaufort

Carel Godin de Beaufort Claude Ballot-Léna

Claude Ballot-Léna Colin Davis

Colin Davis Derek Bell[23]

Derek Bell[23] Dieter Glemser

Dieter Glemser Dirk Werner

Dirk Werner Earl Bamber

Earl Bamber Edgar Barth[24]

Edgar Barth[24] Gerhard Mitter[25]

Gerhard Mitter[25] Gérard Larrousse

Gérard Larrousse Günter Klass

Günter Klass Hans Herrmann

Hans Herrmann Hans-Joachim Stuck[26]

Hans-Joachim Stuck[26] Heinz Schiller

Heinz Schiller Helmut Marko[27]

Helmut Marko[27] Henri Pescarolo

Henri Pescarolo Herbert Linge[28]

Herbert Linge[28] Herbert Müller[29]

Herbert Müller[29] Hurley Haywood[30]

Hurley Haywood[30] Hélio Castroneves

Hélio Castroneves Jacky Ickx[31]

Jacky Ickx[31] Jean Behra

Jean Behra Jo Bonnier

Jo Bonnier Jo Siffert[32]

Jo Siffert[32] Jochen Mass

Jochen Mass Jochen Neerpasch

Jochen Neerpasch Jochen Rindt

Jochen Rindt Joe Buzzetta

Joe Buzzetta John Andretti

John Andretti Jörg Bergmeister

Jörg Bergmeister Jörg Müller

Jörg Müller Jürgen Barth[33]

Jürgen Barth[33] Kees Nierop

Kees Nierop Kurt Ahrens Jr.

Kurt Ahrens Jr. Lucas Luhr

Lucas Luhr Manfred Schurti

Manfred Schurti Marc Lieb

Marc Lieb Marco Holzer

Marco Holzer Mark Donohue[34]

Mark Donohue[34] Mario Andretti

Mario Andretti Mark Webber

Mark Webber Michael Andretti

Michael Andretti Patrick Pilet

Patrick Pilet Peter Gregg[35]

Peter Gregg[35] Reinhold Joest[36]

Reinhold Joest[36] Richard von Frankenberg[37]

Richard von Frankenberg[37] Rolf Stommelen

Rolf Stommelen Rudi Lins

Rudi Lins Ryan Briscoe

Ryan Briscoe Stefan Bellof[38]

Stefan Bellof[38] Steve Luvender

Steve Luvender Sven Müller

Sven Müller Thierry Boutsen

Thierry Boutsen Timo Bernhard

Timo Bernhard Tony Dron

Tony Dron Tony Maggs

Tony Maggs Udo Schütz

Udo Schütz Umberto Maglioli

Umberto Maglioli Uwe Alzen

Uwe Alzen Vern Schuppan[39]

Vern Schuppan[39] Vic Elford

Vic Elford Walter Röhrl

Walter Röhrl Willi Kauhsen

Willi Kauhsen Wolf Henzler

Wolf Henzler Wolfgang Graf Berghe von Trips[40]

Wolfgang Graf Berghe von Trips[40] Patrick Long[41]

Patrick Long[41]

Major victories and championships

- 12 World Sportscar Championship Manufacturers' and Team Titles: 1969, 1970, 1971, 1976, 1977, 1978, 1979, 1982, 1983, 1984, 1985, 1986

- 3 FIA World Endurance Championship Manufacturers' Titles: 2015, 2016, 2017

- 6 World Sportscar Championship Drivers' Titles: 1981, 1982, 1983, 1984, 1985, 1986

- 3 FIA World Endurance Championship Drivers' Titles: 2015, 2016, 2017

- 2 FIA World Endurance Championship GT Manufacturers' Titles: 2015, 2018–19

- 2 FIA World Endurance Championship GT Drivers' Titles: 2015, 2018-19

- 1 Intercontinental Le Mans Cup GT2 Team Title: 2010

- 19 24 Hours of Le Mans: 1970, 1971, 1976, 1977, 1979, 1981, 1982, 1983, 1984, 1985, 1986, 1987, 1994, 1996, 1997, 1998, 2015, 2016, 2017

- 18 12 Hours of Sebring: 1960, 1968, 1971, 1973, 1976, 1977, 1978, 1979, 1980, 1981, 1982, 1983, 1984, 1985, 1986, 1987, 1988, 2008

- 19 Daytona 24 Hours as Manufacturer: 1968, 1970, 1971, 1973, 1975, 1977, 1978, 1979, 1980, 1981, 1982, 1983, 1985, 1986, 1987, 1989, 1991, 2003, 2024

- 13 24 Hours Nürburgring as Manufacturer: 1976, 1977, 1978, 1988, 1993, 2000, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2011, 2018, 2021

- 8 Spa 24 Hours as Manufacturer: 1967, 1968, 1969, 1993, 2003, 2010, 2019, 2020

- 1 Petit Le Mans: 2015

- 11 Targa Florio: 1956, 1959, 1960, 1963, 1964, 1966, 1967, 1968, 1969, 1970, 1973

- 3 IMSA Supercar-Series: 1991, 1992, 1993

- 6 German Racing Championship (DRM): 1977, 1979, 1982, 1983, 1984, 1985

- 20 European Hill Climbing Championship

- 15 IMSA Supercar-Race (US)

- 1 International Championship for Manufacturers: 1970

- 4 Rallye Monte Carlo: 1968, 1969, 1970, 1978

- 2 Paris-Dakar Rally: 1984, 1986

- 12 Formula E victories: 1 win; 2022, 4 wins; 2023, 7 wins; 2024

- 1 Formula E Drivers' Champion: 2024

- 1 Formula One victory: 1962

TAG-Porsche engine in McLaren cars

- 3 Formula One World Drivers' Championships: 1984, 1985, 1986

- 2 Formula One World Constructors' Championships: 1984, 1985

- 25 Formula One victories: 1984, 12 wins; 1985, 6 wins; 1986, 4 wins; 1987, 3 wins

References

Notes

- ^ Watkins, Gary (7 March 2007). "Warehouse Shopping: Inside Porsche's Motorsport Centre". AutoWeek. Archived from the original on 8 November 2011. Retrieved 14 April 2007.

- ^ "Excellence :: Back Issues". Excellence-mag.com. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- ^ "The Porsche Club of America". Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 12 April 2007.

- ^ a b Smith, Roy (2014). The Porsche 924 Carrera. Veloce Publishing Limited.

- ^ Long, Brian (2008). Porsche Racing Cars 1976 to 2005. Veloce Publishing Limited.

- ^ Porsche quits WEC LMP1 class for Formula E programme - Gary Watkins, Autosport, 28 July 2017

- ^ "Porsche and Penske join forces for 2023 WEC return". Autocar. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ^ Klein, Reinhard (2000). Rally Cars, pages 122-123. Germany: Konemann Inc.

- ^ "Lucky espace: the Porsche V12". Autosport. 22 May 2013. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- ^ "Porsche's shock F1 return". Autocar. 1 October 2010. Archived from the original on 3 April 2012. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- ^ "Audi, Porsche to join Formula One, VW CEO says". Reuters. 2 May 2022. Retrieved 2 May 2022.

- ^ "Leak durch Kartellbehörde: Porsche übernimmt 50 Prozent von Red Bull!". Motorsport-Total.com (in German). Retrieved 27 July 2022.

- ^ "Porsche, más cerca de la F1: registra la marca "F1nally"". SoyMotor.com (in Spanish). Retrieved 23 August 2022.

- ^ "Partnership between Porsche AG and Red Bull GmbH will not come about". Porsche Newsroom. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ^ Brittle, Cian (22 March 2023). "Report: Porsche rules out F1 entry in 2026". www.blackbookmotorsport.com. Retrieved 1 August 2023.

- ^ Future looks dim for Porsche - Joseph Siano, The New York Times, 1 July 1990

- ^ Smith, Steven (1 February 2010). "Action Express pulls off a stunning win at the Rolex 24 Hours of Daytona". AutoWeek. Archived from the original on 15 October 2012. Retrieved 1 February 2010.

- ^ "Porsche Reveal Major Shake-Up In Factory Driver Roster". dailysportscar.com. 12 December 2020.

- ^ "Dane Cameron & Felipe Nasr Confirmed As 2022 Porsche Works Drivers". dailysportscar.com. 18 December 2021.

- ^ "António Félix da Costa becomes new Porsche works driver in Formula E". Porsche Newsroom. 15 August 2022.

- ^ "Björn Waldegård – the first World Rally Champion". porsche.de. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ^ "Bob Wollek – Decades for Motorsports". porsche.de. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ^ "Derek Bell – a Porsche ambassador to this day". porsche.de. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ^ "Edgar Barth – three-times winner of the European Hill Climb Championship". porsche.de. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ^ "Gerhard Mitter – Targa Florio winner in the Porsche 908". porsche.de. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ^ "Hans-Joachim Stuck – a man with brains". porsche.de. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ^ "Helmut Marko – the doctor in the cockpit". porsche.de. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ^ "Herbert Linge – 'Mr Do Everything' at Porsche". porsche.de. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ^ "Herbert Müller – the fast semi-professional from Switzerland". porsche.de. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ^ "Hurley Haywood – master of endurance". porsche.de. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ^ "Jacky Ickx – four-time winner in Le Mans". porsche.de. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ^ "Jo Siffert – the naturally talented Swiss". porsche.de. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ^ "Jürgen Barth – at work everywhere for Porsche". porsche.de. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ^ "Mark Donohue – the fastest man in the 917". porsche.de. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ^ "Peter Gregg". porsche.de. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ^ "Reinhold Joest – sustained success at Le Mans". porsche.de. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ^ "Richard von Frankenberg – journalist in a racing car". porsche.de. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ^ "Stefan Bellof – the super-fast golden boy". porsche.de. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ^ "Vern Schuppan". porsche.de. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ^ "Wolfgang Graf Berghe von Trips – Hill Climb Champion with Porsche". porsche.de. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ^ Dagys, John (11 November 2021). "Long to Retire from Full-Time Driving; New Roles at Porsche". sportscar365.com. John Dagys Media.

Bibliography

- Ludvigsen, Karl (2019). Porsche: Excellence Was Expected – Book 1: Surpassing Expectations (1948-1971) (All new ed.). Cambridge, MA, USA: Bentley Publishers. ISBN 9780837617701.

- ——————— (2019). Porsche: Excellence Was Expected – Book 2: Hitting the Apex (1967-1989) (All new ed.). Cambridge, MA, USA: Bentley Publishers. ISBN 9780837617718.

- ——————— (2019). Porsche: Excellence Was Expected – Book 3: Comeback (1982-2008) (All new ed.). Cambridge, MA, USA: Bentley Publishers. ISBN 9780837617725.

- ——————— (2019). Porsche: Excellence Was Expected – Book 4: 21st Century (2002-2020) (All new ed.). Cambridge, MA, USA: Bentley Publishers. ISBN 9780837617732.

- Oursler, Bill (2000). Porsche Racing Cars: A History of Factory Competition. Osceola, WI, USA: MBI Publishing Company. ISBN 076030727X.

- Staud, René (2022). Porsche Legends: The Racing Icons from Zuffenhausen. Bielefeld, Germany: Delius Klasing. ISBN 9783667125316.

- Stone, Matt (2021). The IROC Porsches: The International Race of Champions, Porsche’s 911 RSR, and the Men Who Raced Them. Beverly, MA, USA: Motorbooks. ISBN 9780760368251.