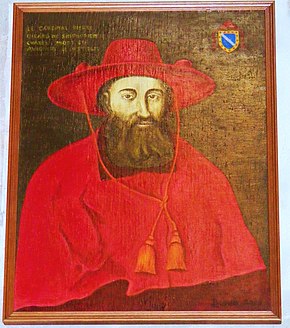

Pierre Girard (cardinal)

Pierre Girard[1] was born in the commune of Saint-Symphorien-sur-Coise, in the Department of Rhone, once in the ancient County of Forez. He died in Avignon on 9 November 1415. He was Bishop of Lodeve and then Bishop of Le Puy. He was a cardinal of the Avignon Obedience during the Great Western Schism, and was promoted to the Bishopric of Tusculum (Frascati). His principal work, however, was as a courtier and administrator at Avignon, and as a papal diplomat.

Early career

In his Testament, Pierre Girard mentions a brother, Jean Terralli, and several consanguinei: Jean Girard (who has children), John's sister Margarita, Lucia the wife of Jean Arnaudi, and Joannes Polerii.[2]

Pierre began his education as a choir boy in the Choir School of the Cathedral of Saint Jean in Lyon, called the Manécanterie ('morning chant').[3]

Pierre was Archdeacon of Bourges by 9 February 1373.[4] He held the Licenciate in Civil and Canon Law by 1374.[5] He was a cleric of the Apostolic Chamber (the papal finance ministry), and Canon and Provost of Marseille from 1374 to 1382.[6]

On 8 June 1381, Girard was named papal Nuncio to France (Apostolicae Sedis in lingua gallicana nuncio) by Pope Clement VII "for certain difficult business for the Pope and the Holy Roman Church", and was particularly ordered to investigate the situation in the diocese of Nantes, where the diocese was being administered by procurators appointed by the bishop on the alleged grounds that he was aged and "lacking in discretion".[7] There was disorder everywhere, caused by the Great Western Schism, and Pope Clement was obviously interested in supporting bishops who supported him, against obstinate supporters of Urban VI. By 4 September 1381 Pierre was being addressed by the Pope as electus Lodovensis. He had received a major promotion for his work.

Episcopate

Girard was granted his bulls as Bishop of Lodève by Pope Clement VII on 17 October 1382. On 29 October he was found in Paris, with the Bishops of Paris and Geneva, sent to punish a Collector of the Apostolic Chamber who had committed various crimes.[8]

Girard was transferred to the diocese of Le Puy on 17 July 1385 by Pope Clement VII.[9] He was installed by proxy on 30 July, and in person on 22 September 1388.[10] He held the See until his promotion to the Cardinalate in 1390.[11]

In 1386, two of Urban VI's cardinals, Pileus de Prata and Galeozzo de Petramala, withdrew from Urban's allegiance and joined that of Clement VII. Clement sent Bishop Girard to bring the two cardinals a proper red hat, and on 13 June 1387 Cardinal de Prata was named Cardinal Priest of Santa Prisca, while Cardinal de Petramalari was named Cardinal Deacon of San Giorgio in Velabro on 5 May 1388.[12]

On 15 November 1388, Girard was present at the deathbed of Cardinal Pierre de Cros, as he made his Last Will and Testament.[13]

Cardinalate

Pierre Girard was created a cardinal by Pope Clement VII on 17 October 1390, and assigned the titular church of San Pietro in Vincoli on 21 December 1390.[14]

Clement VII died in Avignon on 16 September 1394. When the news reached Paris on 23 September, the University of Paris immediately sent a delegation to the King. They argued that the moment had arrived to heal the schism, and they requested the King to intervene with the Cardinals to postpone the election of a new pope. Time was needed for multiple consultations as to the best way forward, and the King should even consult with the pope of the Roman Obedience, Boniface IX, in the hope of coming to some sort of agreement. The King consulted with his royal Council, and decided to send Renaud de Roye to Avignon immediately with a letter from the King. The Conclave, however, began on September 26, though before the Conclave was locked up, a fast messenger from the King brought a royal letter. The Cardinals, believing that they knew what was in the message, decided not to open it until the Conclave was over. They thereby preserved their canonical rights. Cardinal Girard participated in the Conclave of 1394, which then went forward. Cardinal Pedro de Luna was elected on 28 September 1394, and took the name Benedict XIII. The opportunity to heal the schism had been missed.[15]

Cardinal Girard was named Suburbicarian Bishop of Tusculum (Frascati) in 1402 by Pope Benedict XIII.[16] He was also named Major Penitentiary.[17] He still held the office when he signed his Testament at Bologna in November 1410 under John XXIII.[18]

Repudiation of Benedict XIII

On 2 February 1395 a meeting of the French clergy was convened in the royal palace in Paris in the name of King Charles VI, for the purpose of tendering advice to the King as to the means to end the Great Western Schism, which had been going on for nearly seventeen years, with no signs of resolution. Over 150 letters of summons were issued. The consensus of the meeting was that the "Way of Cession" (resignation of both contenders and election of a new pope for both Obediences) was the most efficient solution. The three royal dukes, Berri, Bourbon and Anjou, who had in fact inspired the meeting, were sent to lead a delegation to discuss the matter with Benedict XIII in Avignon.[19] Conferences with the Pope took place at the end of June in Villeneuve, where the Pope was staying at the time, but the Pope finally withdrew from personal attendance, saying it was beneath the papal dignity to negotiate in public.[20] The three dukes then held a consultation with the Cardinals in the Duke de Bourbon's residence in Avignon, and each cardinal was asked in turn for his opinion on the various proposals to resolve the schism. Cardinal Girard pronounced in favor of the "Way of Cession", stating that Clement VII on several occasions had promised that he would resign the papacy to save the Church.[21]

Cardinal Girard was already working with the French Court and Benedict XIII to maintain cordial relations. On 25 May 1385, in his capacity as Major Penitentiary, he granted faculties to the Bishop of Paris to dispense four couples who wished to marry from the impediment of close relationship to the fourth degree of kinhood. It happened that one such couple in the diocese of Paris were Isabelle, daughter of King Charles VI, and her betrothed, King Richard II of England. Evidently Benedict XIII did not want to be seen to be too closely linked to the French monarchy, and his fertile mind as a former professor of Canon Law saw in the Major Penitentiary a way to do what was necessary without attracting public criticism of being a tool of the King of France.[22]

On 1 September 1398 at Villeneuve eighteen cardinals, among them Pierre Girard, published the retraction of their obedience to Benedict XIII. A few weeks later, after negotiations with the pontiff, they returned to their obedience.[23]

In 1407 Cardinal Girard returned to his birthplace in Saint-Symphorien,[24] where he built a church and established in it a College of Canons. The church was the recipient of generous benefactions in the Cardinal's Testament.[25]

Council of Pisa and Conclaves

On 29 June 1408, thirteen cardinals (who held the proxies of two additional cardinals) met in the port city of Livorno in Italy, where they prepared a manifesto, in which they pledged themselves to summon a general council of the Church to solve the problem of the Great Western Schism. One of them was Pierre Girard, Cardinal Bishop of Tusculum (Frascati).[26] When the Council finally met on 25 March 1409, Girard was a prominent member of the Council. When the vote was called for on 10 May 1409 in the matter of deposing and anathematizing Benedict XIII and Gregory XII, the vote was nearly unanimous, except for Cardinal Guy de Malsec and Cardinal Niccolò Brancaccio, who asked for more time to consider.[27] The sentence was finally read on 5 June.

Cardinal Girard was one of the twenty-four cardinals who took part in the Conclave that was held during the Council of Pisa, from 15 June to 26 June 1409. Cardinal Pietro Filargo was elected, and chose the name Alexander V.[28] Unfortunately he survived only 10½ months, but during that time, in a gesture intended to heal the wounds of the schism, he issued a papal decree legitimizing all of the cardinals of all the obediences.

Cardinal Girard participated in the Conclave of 1410 in Bologna.[29]

Cardinal Pierre Girard composed his Testament at Bologna in the house of the Servants of Mary on 7 November 1410, the first year of Pope John XXIII. The Notary remarks that the document filled six large folio pages. In addition to Cardinal Niccolò Brancaccio and Jean Allarmet de Brogny one of the executors was a consanguineus of Cardinal Girard, Joannes Polerii, Bachelor of Laws and Sacristan of the Cathedral of Saint Paul in London.[30] The testament remarks that at the time he possessed thirty benefices, twenty-six of which were priories.[31] He died in Avignon on 9 November 1415. He was buried at Saint-Symphorien-sur-Coise, in the crypt of the Collegiate Church on the summit of the hill, on the Rue Cardinal Giraud, which the Cardinal had built.[32] This was in accordance with his Last Will and Testament.[33]

Notes and References

- ^ Girard is sometimes spelled Guerard or Gérard, Gerardi or Geraudi. He is sometimes called De Podio, but that is only the Latin form of his diocese Le Puy (Aniciensis). Early authors, Ciaconius and Fantoni, placed his birth at the Chateau du Puy, in the Limousin, based on this mistake, as though Le Puy (de Podio) was a reference to his birthplace. L. Cardella Memorie de' Cardinali II (Roma 1793), p. 361.

- ^ François Du Chesne (1660). Preuves De L'Histoire De Tous Les Cardinaux François De Naissance: (in French and Latin). Paris: Du Chesne. pp. 563–564, 567.

- ^ Eremita peregrinus, "French Cathedrals, XXVI: Lyon," The Churchman. Vol. 81. New York: Churchman Company. 1900. pp. 298–302, at 302.

- ^ Denis de Saint-Marthe (1739). Gallia Christiana, In Provincias Ecclesiasticas Distributa. Vol. Tomus sextus (nova ed.). Paris: Ex Typographia Regia. pp. 558–559.

- ^ J. H. Albanés; Ulysse Chevalier (1899). Gallia christiana novissima: Marseille (Évêques, prévots, statuts) (in French and Latin). Montbeliard: Société anonyme d'imprimerie montbéliardaise. p. 808.

- ^ Eubel, p. 310. Albanés & Chevalier, pp. 808–816.

- ^ Albanés & Chevalier, pp. 811-812.

- ^ Eubel, p. 310. Albanés & Chevalier, p. 812-813.

- ^ Albanés & Chevalier, p. 813-814.

- ^ Baluze, p. 1387. Obviously Girard was not a residential bishop; Le Puy was only a benefice. He is on record as being in Avignon on 10 October 1387, when he dined with Jean Fabri, Bishop of Chartres, the diarist.

- ^ Denis de Sainte-Marthe (1720). Gallia Christiana (in Latin). Vol. Tomus secundus. Paris: Ex Typographia Regia. p. 729. Eubel, pp. 91-92.

- ^ Eubel, p. 23; Sainte-Marthe, Gallia Christiana II, p. 729.

- ^ Sainte-Marthe, Gallia christiana II, p. 729. Baluze, p.

- ^ Eubel, p. 28, no. 32. Albanés & Chevalier, p. 816.

- ^ Valois III (1902), p. 1-7. J. P. Adams, Sede Vacante 1394; retrieved: 2017-09-23.

- ^ Eubel, p. 39.

- ^ Sainte-Marthe, Gallia christiana II, p. 729.

- ^ From July 1409 until January 1412 he appears to have had a colleague, Cardinal Antonio Caetani, who had been Patriarch of Aquileia and Bishop of Palestrlna in the Roman Obedience. When Caetani joined the Council of Pisa and the Obedience of Alexander V, he had to give up the Bishopric of Palestrina, which already belonged to Cardinal Guy de Malsec, the Dean of the Sacred College. In compensation, Alexander V named him Bishop of Porto and Santa Rufina and Major Penitentiary. Before he joined the Council of Pisa he had been given the faculties by Gregory XII of the Roman Obedience to correct and reform the Minores Poenitentiarii, and apparently the appointment was continued. Cardinal Caetani died on 2 or 11 January 1412. Ciaconius II, p. 709. Eubel, p. 26, no. 5.

- ^ Mandell Creighton (1882). A History of the Papacy during the Period of the Reformation. Vol. I: The great schism. The Council of Constance, 1378–1418. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin & Company. pp. 129–133.

- ^ Valois, III (1901), pp. 27–43.

- ^ Baluze, p. 1377.

- ^ Valois (1901) III, p. 102.

- ^ Baluze, p. 1351. Martin de Alpartils, Chronica Actitatorum I (Paderborn 1906) (ed. Ehrle) p. 35. In the list of cardinals, Girard is identified as being Major Penitentiarius.

- ^ His Testament identifies the town as Sanctus Symphorianus Castri. The location of this town was long a matter of controversy. Baluze (1693), p. 1386, already notes that Saint-Saforin d'Ozon between Lyon and Vienne is wrong. There are at least twenty-two communes in modern France called Saint-Symphorien. It is not the Saint-Symphorien-le-Château. Early authors, Ciaconius and Fantoni, placed his birth at the Chateau du Puy, in the Limousin. Cardella Memorie de' Cardinali II (Roma 1793), p. 361.

- ^ Baluze, p. 1387. François Du Chesne (1660). Histoire de tous les cardinaux françois de naissance (in French). Paris: Duchesne. p. 712.

- ^ Valois IV (1902), pp. 13–14. Agreement of the Cardinals at Livorno, retrieved: 2017-09-19.

- ^ Valois IV (1902), p. 99.

- ^ J. P. Adams, Sede Vacante 1409, retrieved: 2017-09-19.

- ^ J. P. Adams, Sede Vacante 1410; retrieved: 2017-09-22.

- ^ Fisquet, p. 358. The Testament and its Codicil of 10 November are printed in François Du Chesne (1660). Preuves De L'Histoire De Tous Les Cardinaux François De Naissance (in French and Latin). Paris: Du Chesne. pp. 550–570.

- ^ Sainte-Marthe, Gallia christiana II, p. 729.

- ^ Augustus John Hare (1890). South-eastern France. London: G. Allen. p. 162.

- ^ Duchesne, p. 551.

Bibliography

- C***, J.-P.-D. (1703). Girard. Recueil des principales actions de l'éminentissime cardinal Pierre Girard, de St Symphorien-le-Châtel (in French). Lyon: Pierre Thened.

- Baluze, Étienne (Stephanus) (1693). Vitae Paparum Avenionensis: hoc est, historia pontificum romanorum qui in Gallia sederunt do anno Christi MCCCV usque ad annum MCCCXCIV (in Latin). Vol. Tomus primus. Paris: apud Franciscum Muguet. pp. 1386–1388.

- Baronio, Cesare (1872). Theiner, Augustinus (ed.). Annales ecclesiastici (in Latin). Vol. Tomus vigesimus sextus (26): 1356-1396. Bar-le-Duc: Typis et sumptibus Ludovici Guerin.

- Cardella, Lorenzo (1793). Memorie storiche de'cardinali della santa Romana chiesa (in Italian). Vol. Tomo secondo. Roma: Pagliarini. pp. 351–352.

- Chacón (Ciaconius), Alfonso (1677). A. Oldoino (ed.). Vitae, et res gestae pontificum Romanorum et s.r.e. cardinalium (in Latin). Vol. Tomus secundus. Roma: P. & A. de Rubeis (Rossi). p. 676.

- Eubel, Conradus, ed. (1913). Hierarchia catholica medii aevi. Vol. Tomus 1 (second ed.). Münster: Libreria Regensbergiana.

- Fisquet, Honore (1864). La France pontificale (Gallia Christiana): Metropole de Lyon et Vienne: Lyon (in French). Paris: Etienne Repos. p. 357.

- Valois, Noël (1896). La France et le grand schisme d'Occident: Le schisme sous Charles V. Le schisme sous Charles VI jusqu'à la mort de Clément VII (in French). Vol. Tome premier. Paris: A. Picard et fils.

- Valois, Noël (1901). La France et le grand schisme d'Occident: Efforts de La France pour obtenir l'abdication des deux pontifes rivaux (in French). Vol. Tome III. Paris: A. Picard et fils.

- Valois, Noël (1902). La France et le grand schisme d'Occident: Recours au Concile général (in French). Vol. Tome IV. Paris: A. Picard et fils.

External links

- Mairie de Saint-Symphorien, Visites guidées de l'église Collégiale, retrieved: 2017-09-21.(in French)