Pickling

Pickling is the process of preserving or extending the shelf life of food by either anaerobic fermentation in brine or immersion in vinegar. The pickling procedure typically affects the food's texture and flavor. The resulting food is called a pickle, or, if named, the name is prefaced with the word "pickled". Foods that are pickled include vegetables, fruits, mushrooms, meats, fish, dairy and eggs.

Pickling solutions are typically highly acidic, with a pH of 4.6 or lower,[1] and high in salt, preventing enzymes from working and micro-organisms from multiplying.[2] Pickling can preserve perishable foods for months, or in some cases years.[3] Antimicrobial herbs and spices, such as mustard seed, garlic, cinnamon or cloves, are often added.[4] If the food contains sufficient moisture, a pickling brine may be produced simply by adding dry salt. For example, sauerkraut and Korean kimchi are produced by salting the vegetables to draw out excess water. Natural fermentation at room temperature, by lactic acid bacteria, produces the required acidity. Other pickles are made by placing vegetables in vinegar. Like the canning process, pickling (which includes fermentation) does not require that the food be completely sterile before it is sealed. The acidity or salinity of the solution, the temperature of fermentation, and the exclusion of oxygen determine which microorganisms dominate, and determine the flavor of the end product.[5]

When both salt concentration and temperature are low, Leuconostoc mesenteroides dominates, producing a mix of acids, alcohol, and aroma compounds. At higher temperatures Lactobacillus plantarum dominates, which produces primarily lactic acid. Many pickles start with Leuconostoc, and change to Lactobacillus with higher acidity.[5]

History

Pickling with vinegar likely originated in ancient Mesopotamia around 2400 BCE.[6][7] There is archaeological evidence of cucumbers being pickled in the Tigris Valley in 2030 BCE.[8] Pickling vegetables in vinegar continued to develop in the Middle East region before spreading to the Maghreb, to Sicily and to Spain. From Spain it spread to the Americas.[9] On the other hand, fermented salt pickling reportedly has its origins in China.[6]

Pickling was used as a way to preserve food for out-of-season use and for long journeys, especially by sea. Salt pork and salt beef were common staples for sailors before the days of steam engines. Although the process was invented to preserve foods, pickles are also made and eaten because people enjoy the resulting flavors. Pickling may also improve the nutritional value of food by introducing B vitamins produced by bacteria.[10]

Etymology

The English term "pickle" first appears around 1400 CE. It is from Middle English pikel, a spicy sauce served with meat or fish, borrowed from Middle Dutch or Middle Low German pekel ("brine") but later referred to preserving in brine or vinegar.[9][11]

In world cuisines

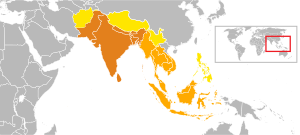

Asia

South Asia

South Asia has a large variety of pickles (known as achar (अचार, اچار) in Nepali, Assamese, Bengali, Hindi (अचार), Punjabi, Gujarati, Urdu (اچار) uppinakaayi in Kannada, lonacha (लोणचं) in Marathi, uppilittathu or achar in Malayalam, oorukai in Tamil, pacchadi(పచ్చడి) or ooragaya(ఊరగాయ) in Telugu, which are mainly made from varieties of mango, lemon, lime, gongura (a sour leafy shrub), tamarind, Indian gooseberry (amla), and chilli. Vegetables such as eggplant, carrots, cauliflower, tomato, bitter gourd, green tamarind, ginger, garlic, onion, and citron are also occasionally used. These fruits and vegetables are mixed with ingredients such as salt, spices, and vegetable oils. The pickling process is completed by placing filled jars in the sun where they mature in the sun. The sun's heat destroys moulds and microbes which could spoil the pickles.[2][9]

In Pakistan, pickles are known locally as achaar (in Urdu اچار) and come in a variety of flavours. A popular item is the traditional mixed Hyderabadi pickle, a common delicacy prepared from an assortment of fruits (most notably mangoes) and vegetables blended with selected spices. Although the origin of the word is ambiguous, the word āchār is widely considered to be of Persian origin. Āchār in Persian is defined as 'powdered or salted meats, pickles, or fruits, preserved in salt, vinegar, honey, sugar or syrup.'[12]

In Sri Lanka, a date and shallot pickle achcharu is traditionally prepared from carrots, chilli powder, shallots and ground dates mixed with garlic, crushed fresh ginger, green chilis, mustard seeds and vinegar, and left to sit in a clay pot.[13]

Indian pickles are mostly prepared in three ways: salt/brine, oil, and vinegar, with mango pickle being most popular among all.[14][15]

Southeast Asia

Singapore, Indonesian and Malaysian pickles, called acar are typically made out of cucumber, carrot, bird's eye chilies, and shallots, these items being seasoned with vinegar, sugar and salt. Fruits, such as papaya and pineapple, are also sometimes pickled.

In the Philippines, pickling is a common method of preserving food, with many commonly eaten foods pickled, traditionally done using large earthen jars. The process is known as buro or binuro. Pickling was a common method of preserving a large variety of foods such as fish throughout the archipelago before the advent of refrigeration, but its popularity is now confined to vegetables and fruits. Atchara is primarily made out of julienned green papaya, carrots, and shallots, seasoned with cloves of garlic and vinegar; but could include ginger, bell peppers, white radishes, cucumbers or bamboo shoots. Pickled unripe mangoes or burong mangga, unripe tomatoes, guavas, jicama, bitter gourd and other fruit and vegetables still retain their appeal. Siling labuyo, sometimes with garlic and red onions, is also pickled in bottled vinegar and is a staple condiment in Filipino cuisine.[citation needed]

In Vietnamese cuisine, vegetable pickles are called dưa muối ("salted vegetables") or dưa chua ("sour vegetables"). Dưa chua or dưa góp is made from a variety of fruits and vegetables, including cà pháo, eggplant, Napa cabbage, kohlrabi, carrots, radishes, papaya, cauliflower, and sung. Dưa chua made from carrots and radishes are commonly added to bánh mì sandwiches. Dưa cải muối is made by pressing and sun-drying vegetables such as cải xậy and gai choy. Nhút mít is a specialty of Nghệ An and Hã Tĩnh provinces made from jackfruit.[citation needed]

In Burma, tea leaves are pickled to produce lahpet, which has strong social and cultural importance.[citation needed]

East Asia

A wide variety of foods are pickled throughout East Asia. The pickles are often sweet, salty, and/or spicy and preserved in sweetened solutions or oil.[16]

China is home to a huge variety of pickled vegetables, including radish, baicai (Chinese cabbage, notably suan cai, pao cai, and Tianjin preserved vegetable), zha cai, chili pepper (e.g. duo jiao), and cucumbers, among many others.[citation needed]

Japanese tsukemono (pickled foods) include takuan (daikon), umeboshi (ume plum), tataki gobo (burdock root), gari and beni shōga (ginger), turnip, cucumber, and Chinese cabbage.[citation needed]

The Korean staple kimchi is usually made from pickled napa cabbage and radish, but is also made from green onions, garlic stems, chives and a host of other vegetables. Jangajji is another banchan consisting of pickled vegetables.[citation needed]

Western Asia

In Iran, Turkey, Arab countries, the Balkans, and the South Caucasus, pickles (called torshi in Persian, turşu in Turkish language and mekhallel in Arabic) are commonly made from turnips, peppers, carrots, green olives, cucumbers, eggplants, cabbage, green tomatoes, lemons, and cauliflower.[citation needed]

Sauerkraut, as well as cabbage pickled in vinegar, with carrot and other vegetables is commonly consumed as a kosher dish in Israel and is considered pareve, meaning that it contains no meat or dairy so it can be consumed with either.[17]

Europe

Central and Eastern Europe

In Hungary, the main meal (lunch) usually includes some kind of pickles (savanyúság), but pickles are also commonly consumed at other times of the day. The most commonly consumed pickles are sauerkraut (savanyú káposzta), pickled cucumbers and peppers, and csalamádé, but tomatoes, carrots, beetroot, baby corn, onions, garlic, certain squashes and melons, and a few fruits such as plums and apples are used to make pickles too. Stuffed pickles are specialties, usually made of peppers or melons pickled after being stuffed with a cabbage filling. Pickled plum stuffed with garlic is a unique Hungarian type of pickle just like csalamádé and leavened cucumber (kovászos uborka). Csalamádé is a type of mixed pickle made of cabbage, cucumber, paprika, onion, carrot, tomatoes, and bay leaf mixed up with vinegar as the fermenting agent. Leavened cucumber, unlike other types of pickled cucumbers that are around all year long, is rather a seasonal pickle produced in the summer. Cucumbers, spices, herbs, and slices of bread are put in a glass jar with salt water and kept in direct sunlight for a few days. The yeast from the bread, along with other pickling agents and spices fermented under the hot sun, give the cucumbers a unique flavor, texture, and slight carbonation. Its juice can be used instead of carbonated water to make a special type of spritzer ('Újházy fröccs'). It is common for Hungarian households to produce their own pickles. Different regions or towns have their special recipes unique to them. Among them all, the Vecsési sauerkraut (Vecsési savanyú káposzta) is the most famous.[citation needed]

Romanian pickles (murături) are made out of beetroot, cucumbers, green tomatoes (gogonele), carrots, cabbage, garlic, sauerkraut, bell peppers, melons, mushrooms, turnips, celery and cauliflower. Meat, like pork, can also be preserved in salt and lard.[citation needed]

Polish, Czech and Slovak traditional pickles are cucumbers, sauerkraut, peppers, beetroot, tomatoes, but other pickled fruits and vegetables, including plums, pumpkins and mushrooms are also common.[citation needed]

North Caucasian, Russian, Ukrainian and Belarusian pickled items include beets, mushrooms, tomatoes, sauerkraut, cucumbers, ramsons, garlic, eggplant (which is typically stuffed with julienned carrots), custard squash, and watermelon. Garden produce is commonly pickled using salt, dill, blackcurrant leaves, bay leaves and garlic and is stored in a cool, dark place. The leftover brine (called rassol (рассол) in Russian) has a number of culinary uses in these countries, especially for cooking traditional soups, such as shchi, rassolnik, and solyanka. Rassol, especially cucumber or sauerkraut rassol, is also a favorite traditional remedy against morning hangover.[18]

Southern Europe

An Italian pickled vegetable dish is giardiniera, which includes onions, carrots, celery and cauliflower. Many places in southern Italy, particularly in Sicily, pickle eggplants and hot peppers.[citation needed]

In Albania, Bulgaria, Serbia, North Macedonia and Turkey, mixed pickles, known as turshi, tursija or turshu form popular appetizers, which are typically eaten with rakia. Pickled green tomatoes, cucumbers, carrots, bell peppers, peppers, eggplants, and sauerkraut are also popular.[citation needed]

Turkish pickles, called turşu, are made out of vegetables, roots, and fruits such as peppers, cucumber, Armenian cucumber, cabbage, tomato, eggplant (aubergine), carrot, turnip, beetroot, green almond, baby watermelon, baby cantaloupe, garlic, cauliflower, bean and green plum. A mixture of spices flavor the pickles.[citation needed]

In Greece, pickles, called τουρσί(α), are made out of carrots, celery, eggplants stuffed with diced carrots, cauliflower, tomatoes, and peppers.[citation needed]

In Spain, pickles, known as "encurtidos", are mainly made with olives, cucumbers, onions and green peppers ("guindillas" or "piparras"). "Banderillas" are small pieces of pickled cucumber and green pepper, along with olives and anchovies, mounted into toothpicks, and are very popular as Tapas.[citation needed]

Northern Europe

In Britain, pickled onions and pickled eggs are often sold in pubs and fish and chip shops. Pickled beetroot, walnuts, and gherkins, and condiments such as Branston Pickle and piccalilli are typically eaten as an accompaniment to pork pies and cold meats, sandwiches or a ploughman's lunch. Other popular pickles in the UK are pickled mussels, cockles, red cabbage, mango chutney, sauerkraut, and olives. Rollmops are also quite widely available under a range of names from various producers both within and out of the UK.[citation needed]

Pickled herring, rollmops, and salmon are popular in Scandinavia. Pickled cucumbers and red garden beets are important as condiments for several traditional dishes. Pickled capers are also common in Scandinavian cuisine.[citation needed]

North America

In the United States and Canada, pickled cucumbers (most often referred to simply as "pickles"), olives, and sauerkraut are most commonly seen, although pickles common in other nations are also very widely available. In Canada and the US, there may be a distinction made between gherkins (usually smaller), and pickles (larger pickled cucumbers).

Sweet pickles made with fruit are more common in the cuisine of the American South. The pickling "syrup" is made with vinegar, brown sugar, and whole spices such as cinnamon sticks, allspice and cloves. Fruit pickles can be made with an assortment of fruits including watermelon, cantaloupe, Concord grapes and peaches.[19]

Canadian pickling is similar to that of Britain. Through the winter, pickling is an important method of food preservation. Pickled cucumbers, onions, and eggs are common. Pickled egg and pickled sausage make popular pub snacks in much of English Canada. Chow-chow is a tart vegetable mix popular in the Maritime Provinces and the Southern United States, similar to piccalilli. Pickled fish is commonly seen, as in Scotland, and kippers may be seen for breakfast, as well as plentiful smoked salmon. Meat is often also pickled or preserved in different brines throughout the winter, most prominently in the harsh climate of Newfoundland.

Pickled eggs are common in many regions of the United States. Pickled herring is available in the Upper Midwest. Giardiniera, a mixture of pickled peppers, celery and olives, is a popular condiment in Chicago and other Midwestern cities with large Italian-American populations, and is often consumed with Italian beef sandwiches.

Pennsylvania Dutch Country has a strong tradition of pickled foods, including chow-chow and red beet eggs. In the Southern United States, pickled okra and watermelon rind are popular, as are deep-fried pickles and pickled pig's feet, pickled chicken eggs, pickled quail eggs, pickled garden vegetables and pickled sausage.[20][21]

Various pickled vegetables, fish, or eggs may make a side dish to a Canadian lunch or dinner. Popular pickles in the Pacific Northwest include pickled asparagus and green beans. Pickled fruits like blueberries and early green strawberries are paired with meat dishes in restaurants.

Thanksgiving

Pickles were part of Thanksgiving dinner traditions as early as 1827. The first mention of pickles at Thanksgiving comes from Sarah Josepha Hale's novel Northwood. (Hale is best known for her successful campaign to have Thanksgiving recognized as a national holiday in the United States.) Pickled peaches, coleslaw and other mixed pickles continue to be served alongside cranberry sauce at Thanksgiving dinner in present times.[22]

Mexico, Central America, and South America

In Mexico, chili peppers, particularly of the Jalapeño and serrano varieties, pickled with onions, carrots and herbs form common condiments.[citation needed]

In the Mesoamerican region, pickling is known as encurtido or "curtido" for short. The pickles or "curtidos" as known in Latin America are served cold, as an appetizer, as a side dish or as a tapas dish in Spain. In several Central American countries it is prepared with cabbage, onions, carrots, lemon, vinegar, oregano, and salt. In Mexico, "curtido" consists of carrots, onions, and jalapeño peppers and used to accompany meals common in taquerías and restaurants.[citation needed]

Another example of a type of pickling which involves the pickling of meats or seafood is the "escabeche" or "ceviches" popular in Peru, Ecuador, and throughout Latin America and the Caribbean. These dishes include the pickling of pig's feet, pig's ears, and gizzards prepared as an "escabeche" with spices and seasonings to flavor it. The ceviches consist of shrimp, octopus, and various fishes seasoned and served cold.[citation needed]

Process

In traditional pickling, fruit or vegetables are submerged in brine (20–40 grams/L of salt (3.2–6.4 oz/imp gal or 2.7–5.3 oz/US gal)), or shredded and salted as in sauerkraut preparation, and held underwater by flat stones layered on top.[23] Alternatively, a lid with an airtrap or a tight lid may be used if the lid is able to release pressure which may result from carbon dioxide buildup.[24] Mold or (white) kahm yeast may form on the surface; kahm yeast is mostly harmless but can impart an off taste and may be removed without affecting the pickling process.[25]

In chemical pickling, the fruits or vegetables to be pickled are placed in a sterilized jar along with brine, vinegar, or both, as well as spices, and are then allowed to mature until the desired taste is obtained.

The food can be pre-soaked in brine before transferring to vinegar. This reduces the water content of the food, which would otherwise dilute the vinegar. This method is particularly useful for fruit and vegetables with a high natural water content.

In commercial pickling, a preservative such as sodium benzoate or EDTA may also be added to enhance shelf life. In fermentation pickling, the food itself produces the preservation agent, typically by a process involving Lactobacillus bacteria that produce lactic acid as the preservative agent.

Alum, short for aluminum sulfate, is used in pickling to promote crisp texture and is approved, though not recommended, as a food additive by the United States Food and Drug Administration.[26][27] Another common crisping agent is calcium chloride, which evolved from the practice of using pickling lime.[28] See also firming agent.

"Refrigerator pickles" are unfermented pickles made by marinating fruit or vegetables in a seasoned vinegar solution. They must be stored under refrigeration or undergo canning to achieve long-term storage.[29]

Japanese Tsukemono use a variety of pickling ingredients depending on their type, and are produced by combining these ingredients with the vegetables to be preserved and putting the mixture under pressure.

Possible health hazards of pickled vegetables

In 1993, the World Health Organization listed traditional Asian pickled vegetables as possible carcinogens,[30] and the British Journal of Cancer released an online 2009 meta-analysis of research on pickles as increasing the risks of esophageal cancer. The report, citing limited data in a statistical meta analysis, indicates a potential two-fold increased risk of esophageal cancer associated with Asian pickled vegetable consumption. Results from the research are described as having "high heterogeneity" and the study said that further well-designed prospective studies were warranted.[31] However, their results stated "The majority of subgroup analyses showed a statistically significant association between consuming pickled vegetables and Oesophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma".[31]

Consuming pickled vegetables is also associated with a 28% increase in the risk of stomach cancer.[32]

The 2009 meta-analysis reported heavy infestation of pickled vegetables with fungi. Some common fungi can facilitate the formation of N-nitroso compounds, which are strong esophageal carcinogens in several animal models.[33] Roussin red methyl ester,[34] a non-alkylating nitroso compound with tumour-promoting effect in vitro, was identified in pickles from Linzhou, Henan (formerly Linxian) in much higher concentrations than in samples from low-incidence areas. Fumonisin mycotoxins have been shown to cause liver and kidney tumours in rodents.[31]

A 2017 study in Chinese Journal of Cancer[35] has linked salted vegetables (pickled mustard green common in Chinese cuisine) to a fourfold increase in nasopharynx cancer. The researchers believe possible mechanisms include production of nitrosamines (a type of N-nitroso compound) by fermentation and activation of Epstein–Barr virus by fermentation products.[36][37]

Historically, pickling caused health concerns for reasons associated with copper salts, as explained in the mid-19th century The English and Australian Cookery Book: "The evidence of the Lancet commissioner (Dr. Hassall) and Mr. Blackwell (of the eminent firm of Crosse and Blackwell) went to prove that the pickles sold in the shops are nearly always artificially coloured, and are thus rendered highly unwholesome, if not actually poisonous."

Risk reduction

Reduction of suspected carcinogens from pickled products is a subject of active research.

- Fungi are of interest both for spoilage prevention and reduction of mycotoxins. Some pickle cultures are said to contain bacteria producing natural antifungals.[38]

- Nitrites, responsible for the creation of N-nitroso compounds, are reduced by low pH and/or high temperature.[39] Inclusion of a porcini enzyme (or the whole mushroom) also reduces nitrite content.[40]

Gallery

- Pickled olives

- Pickled vegetables

- Fermented homemade pickled cucumber, chili pepper, garlic, and apple in the hot climate of Indonesia

See also

- Brining – Food processing by treating with brine or salt

- Curing (food preservation)

- Fermentation in food processing – Converting carbohydrates to alcohol or acids using anaerobic microorganisms

- Home canning – Process for preserving foods for storage

- List of pickled foods

- Marination – Process of soaking foods in a seasoned, often acidic, liquid before cooking

- Mixed pickle

- Pickling salt – Fine-grained salt used for manufacturing pickles

- Smoking (cooking)

References

- ^ "Pickle Bill Fact Sheet". 13 March 2008. Archived from the original on 13 March 2008. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- ^ a b Davidson, Alan (2014). The Oxford companion to food. Tom Jaine, Soun Vannithone (3rd ed.). New York, NY. ISBN 978-0-19-967733-7. OCLC 890807357.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Elkus, Grace (3 January 2023). "How Do You Know When It's Time to Throw Out Pickles?". Epicurious. Retrieved 13 July 2024.

- ^ Rhee, MS; Lee, SY; Dougherty, RH; Kang, DH (2003). "Antimicrobial effects of mustard flour and acetic acid against Escherichia coli O157:H7, Listeria monocytogenes, and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium". Appl Environ Microbiol. 69 (5): 2959–63. Bibcode:2003ApEnM..69.2959R. doi:10.1128/aem.69.5.2959-2963.2003. PMC 154497. PMID 12732572.

- ^ a b McGee, Harold (2004). On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen. New York: Scribner, pp. 291–296. ISBN 0-684-80001-2.

- ^ a b Trivedi-Grenier, Leena (2019-07-26). "A world tour of pickles in the Bay Area and how to make them". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2022-11-12.

- ^ Pruitt, Sarah (August 7, 2019). "The Juicy 4,000-Year History of Pickles". HISTORY.

- ^ Avey, Tori (3 September 2014). "History in a Jar: The Story of Pickles". pbs.org. PBS. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- ^ a b c Davison, Jan (May 15, 2018). Pickles : A Global History. London, UK: Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-78023-959-0. OCLC 1048925666.

- ^ "Science of Pickles: Fascinating Pickle Facts – Exploratorium". Exploratorium: the museum of science, art and human perception. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- ^ "pickle | Etymology, origin and meaning of pickle by etymonline". www.etymonline.com. Retrieved 2022-07-28.

- ^ "A Brief History Of The Humble Indian Pickle". Culture Trip. 28 November 2016. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ^ Sivanathan, Prakash K. (2017). Sri Lanka : the cookbook. Niranjala M. Ellawala, Kim Lightbody (First Francis Lincoln ed.). London. ISBN 978-1-78101-213-0. OCLC 988577642.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "A Brief History Of The Humble Indian Pickle". theculturetrip.com. 20 July 2016. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ^ Doctor, Vikram (4 August 2019). "Usha Pickles digest | From spiced mango to drumstick pith: How Usha Prabakaran's book changed the way we tasted pickles". The Economic Times. Archived from the original on 12 October 2019. Retrieved 2023-01-02.

- ^ Chou, Lillian. "Chinese and other Asian Pickles". Flavor and Fortune (Fall 2003 Volume). Institute for the Advancement of the Science And Art Of Chinese Cuisine. Archived from the original on 13 March 2013. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- ^ "Sweet & Spicy Pickled Vegetables". chabad.org.

- ^ Smorodinskaya, Tatiana; Evans-Romaine, Karen; Goscilo, Helena, eds. (2007). Encyclopedia of Contemporary Russian Culture. Routledge. pp. 514–515. ISBN 978-0-415-32094-8.

- ^ Good Housekeeping, July 1907

- ^ Zeldes, Leah A. (2009-12-02). "Eat this! Southern-fried dill pickles, a rising trend". Dining Chicago. Chicago's Restaurant & Entertainment Guide, Inc. Archived from the original on 2020-01-06. Retrieved 2010-08-02.

- ^ "Pickled Pigs Feet Recipe – Real Authentic Pigs Feet Recipes". Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- ^ Davison, Jan. Pickles: A Global History. Reaktion Books.

- ^ Howe, Holly (8 November 2018). "3 Key Items for Keeping Your Ferments Safe". MakeSauerkraut.com.

- ^ Katz, Sandor (8 May 2012). "Aerobic vs Anaerobic Fermentation Controversy". Wild Fermentation. (blog). Retrieved 2023-01-02.

- ^ "Fermenting Jars | How To Choose The Right Fermentation Containers?". Cultures For Health. 2015. Archived from the original on 28 August 2016. Retrieved 2023-01-02.

- ^ Fabricant, Florence (5 May 1993). "Where the Humble Pickle Finally Earns a Place of Honor". The New York Times. (subscription required)

- ^ "Food Additive Status List". US Food and Drug Administration. 25 August 2022. Retrieved 24 November 2022.

- ^ "Crispy Pickles". Penn State Extension.

- ^ "All Pickle Types". thenibble.com. Retrieved 2015-01-22.

- ^ "List of Classifications – IARC Monographs on the Identification of Carcinogenic Hazards to Humans". monographs.iarc.who.int. Retrieved 2024-06-16.

- ^ a b c Islami, F (2009). "Pickled vegetables and the risk of oesophageal cancer: a meta-analysis". British Journal of Cancer. 101 (9): 1641–1647. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6605372. PMC 2778505. PMID 19862003.

- ^ Poorolajal, Jalal; Moradi, Leila; Mohammadi, Younes; Cheraghi, Zahra; Gohari-Ensaf, Fatemeh (2020). "Risk factors for stomach cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Epidemiology and Health. 42: e2020004. doi:10.4178/epih.e2020004. ISSN 2092-7193. PMC 7056944. PMID 32023777.

- ^ Li, MH; Ji, C; Cheng, SJ (1986). "Occurrence of nitroso compounds in fungi-contaminated foods: A review". Nutrition and Cancer. 8 (1): 63–69. doi:10.1080/01635588609513877. PMID 3520493.

- ^ Liu, J. G.; Li, M. H. (1989). "Roussin red methyl ester, a tumor promoter isolated from pickled vegetables". Carcinogenesis. 10 (3): 617–620. doi:10.1093/carcin/10.3.617. PMID 2494003.

- ^ Yong, SK; Ha, TC; Yeo, MC; Gaborieau, V; McKay, JD; Wee, J (7 January 2017). "Associations of lifestyle and diet with the risk of nasopharyngeal carcinoma in Singapore: a case-control study". Chinese Journal of Cancer. 36 (1): 3. doi:10.1186/s40880-016-0174-3. PMC 5219694. PMID 28063457.

- ^ "Study: Salted vegetables increase risk of nose cancer". 16 January 2017. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- ^ "Health". Archived from the original on 23 April 2017. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- ^ Leyva Salas, M; Mounier, J; Valence, F; Coton, M; Thierry, A; Coton, E (8 July 2017). "Antifungal Microbial Agents for Food Biopreservation-A Review". Microorganisms. 5 (3): 37. doi:10.3390/microorganisms5030037. PMC 5620628. PMID 28698479.

- ^ Ding, Zhansheng; Johanningsmeier, Suzanne D.; Price, Robert; Reynolds, Rong; Truong, Van-Den; Payton, Summer Conley; Breidt, Fred (August 2018). "Evaluation of nitrate and nitrite contents in pickled fruit and vegetable products". Food Control. 90: 304–311. doi:10.1016/j.foodcont.2018.03.005. S2CID 90307358.

- ^ Zhang, Weiwei; Tian, Guoting; Feng, Shanshan; Wong, Jack Ho; Zhao, Yongchang; Chen, Xiao; Wang, Hexiang; Ng, Tzi Bun (December 2015). "Boletus edulis Nitrite Reductase Reduces Nitrite Content of Pickles and Mitigates Intoxication in Nitrite-intoxicated Mice". Scientific Reports. 5 (1): 14907. Bibcode:2015NatSR...514907Z. doi:10.1038/srep14907. PMC 4597360. PMID 26446494.