Pentecostalism

| Part of a series on |

| Pentecostalism |

|---|

|

|

|

Pentecostalism or classical Pentecostalism is a Protestant Charismatic Christian movement[1][2][3] that emphasizes direct personal experience of God through baptism with the Holy Spirit.[1] The term Pentecostal is derived from Pentecost, an event that commemorates the descent of the Holy Spirit upon the Apostles and other followers of Jesus Christ while they were in Jerusalem celebrating the Feast of Weeks, as described in the Acts of the Apostles (Acts 2:1–31).[4]

Like other forms of evangelical Protestantism,[5] Pentecostalism adheres to the inerrancy of the Bible and the necessity of the New Birth: an individual repenting of their sin and "accepting Jesus Christ as their personal Lord and Savior". It is distinguished by belief in both the "baptism in the Holy Spirit" and baptism by water, that enables a Christian to "live a Spirit-filled and empowered life". This empowerment includes the use of spiritual gifts: such as speaking in tongues and divine healing.[1] Because of their commitment to biblical authority, spiritual gifts, and the miraculous, Pentecostals see their movement as reflecting the same kind of spiritual power and teachings that were found in the Apostolic Age of the Early Church. For this reason, some Pentecostals also use the term "Apostolic" or "Full Gospel" to describe their movement.[1]

Holiness Pentecostalism emerged in the early 20th century among adherents of the Wesleyan-Holiness movement, who were energized by Christian revivalism and expectation of the imminent Second Coming of Christ.[6] Believing that they were living in the end times, they expected God to spiritually renew the Christian Church and bring to pass the restoration of spiritual gifts and the evangelization of the world. In 1900, Charles Parham, an American evangelist and faith healer, began teaching that speaking in tongues was the Biblical evidence of Spirit baptism. Along with William J. Seymour, a Wesleyan-Holiness preacher, he taught that this was the third work of grace.[7] The three-year-long Azusa Street Revival, founded and led by Seymour in Los Angeles, California, resulted in the growth of Pentecostalism throughout the United States and the rest of the world. Visitors carried the Pentecostal experience back to their home churches or felt called to the mission field. While virtually all Pentecostal denominations trace their origins to Azusa Street, the movement has had several divisions and controversies. Early disputes centered on challenges to the doctrine of entire sanctification, and later on, the Holy Trinity. As a result, the Pentecostal movement is divided between Holiness Pentecostals who affirm three definite works of grace,[6] and Finished Work Pentecostals who are partitioned into trinitarian and non-trinitarian branches, the latter giving rise to Oneness Pentecostalism.[8][9]

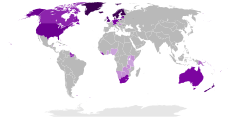

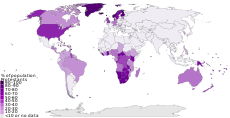

Comprising over 700 denominations and many independent churches, Pentecostalism is highly decentralized.[10] No central authority exists, but many denominations are affiliated with the Pentecostal World Fellowship. With over 279 million classical Pentecostals worldwide, the movement is growing in many parts of the world, especially the Global South and Third World countries.[10][11][12][13][14] Since the 1960s, Pentecostalism has increasingly gained acceptance from other Christian traditions, and Pentecostal beliefs concerning the baptism of the Holy Spirit and spiritual gifts have been embraced by non-Pentecostal Christians in Protestant and Catholic churches through their adherence to the Charismatic movement. Together, worldwide Pentecostal and Charismatic Christianity numbers over 644 million adherents.[15] While the movement originally attracted mostly lower classes in the global South, there is a new appeal to middle classes.[16][17][18] Middle-class congregations tend to have fewer members.[19][20][21] Pentecostalism is believed to be the fastest-growing religious movement in the world.[22]

History

Background

Early Pentecostals have considered the movement a latter-day restoration of the church's apostolic power, and historians such as Cecil M. Robeck Jr. and Edith Blumhofer write that the movement emerged from late 19th-century radical evangelical revival movements in America and in Great Britain.[23][24]

Within this radical evangelicalism, expressed most strongly in the Wesleyan–holiness and Higher Life movements, themes of restorationism, premillennialism, faith healing, and greater attention on the person and work of the Holy Spirit were central to emerging Pentecostalism.[25] Believing that the second coming of Christ was imminent, these Christians expected an endtime revival of apostolic power, spiritual gifts, and miracle-working.[26] Figures such as Dwight L. Moody and R. A. Torrey began to speak of an experience available to all Christians which would empower believers to evangelize the world, often termed baptism with the Holy Spirit.[27]

Certain Christian leaders and movements had important influences on early Pentecostals. The essentially universal belief in the continuation of all the spiritual gifts in the Keswick and Higher Life movements constituted a crucial historical background for the rise of Pentecostalism.[28] Albert Benjamin Simpson (1843–1919) and his Christian and Missionary Alliance (founded in 1887) was very influential in the early years of Pentecostalism, especially on the development of the Assemblies of God. Another early influence on Pentecostals was John Alexander Dowie (1847–1907) and his Christian Catholic Apostolic Church (founded in 1896). Pentecostals embraced the teachings of Simpson, Dowie, Adoniram Judson Gordon (1836–1895) and Maria Woodworth-Etter (1844–1924; she later joined the Pentecostal movement) on healing.[29] Edward Irving's Catholic Apostolic Church (founded c. 1831) also displayed many characteristics later found in the Pentecostal revival.[30]: 131

Isolated Christian groups were experiencing charismatic phenomena such as divine healing and speaking in tongues. The Holiness Pentecostal movement provided a theological explanation for what was happening to these Christians, and they adapted a modified form of Wesleyan soteriology to accommodate their new understanding.[31][32][33]

Early revivals: 1900–1929

Charles Fox Parham, an independent holiness evangelist who believed strongly in divine healing, was an important figure to the emergence of Pentecostalism as a distinct Christian movement. Parham, who was raised as a Methodist,[34] started a spiritual school near Topeka, Kansas in 1900, which he named Bethel Bible School. There he taught that speaking in tongues was the scriptural evidence for the reception of the baptism with the Holy Spirit. On January 1, 1901, after a watch night service, the students prayed for and received the baptism with the Holy Spirit with the evidence of speaking in tongues.[35] Parham received this same experience sometime later and began preaching it in all his services. Parham believed this was xenoglossia and that missionaries would no longer need to study foreign languages. Parham closed his Topeka school after 1901 and began a four-year revival tour throughout Kansas and Missouri.[36] He taught that the baptism with the Holy Spirit was a third experience, subsequent to conversion and sanctification. Sanctification cleansed the believer, but Spirit baptism empowered for service.[37]

At about the same time that Parham was spreading his doctrine of initial evidence in the Midwestern United States, news of the Welsh Revival of 1904–1905 ignited intense speculation among radical evangelicals around the world and particularly in the US of a coming move of the Spirit which would renew the entire Christian Church. This revival saw thousands of conversions and also exhibited speaking in tongues.[38]

Parham moved to Houston, Texas in 1905, where he started a Bible training school. One of his students was William J. Seymour, a one-eyed black preacher. Seymour traveled to Los Angeles where his preaching sparked the three-year-long Azusa Street Revival in 1906.[39] The revival first broke out on Monday April 9, 1906 at 214 Bonnie Brae Street and then moved to 312 Azusa Street on Friday, April 14, 1906.[40] Worship at the racially integrated Azusa Mission featured an absence of any order of service. People preached and testified as moved by the Spirit, spoke and sung in tongues, and fell (were slain) in the Spirit. The revival attracted both religious and secular media attention, and thousands of visitors flocked to the mission, carrying the "fire" back to their home churches.[41] Despite the work of various Wesleyan groups such as Parham's and D. L. Moody's revivals, the beginning of the widespread Pentecostal movement in the US is generally considered to have begun with Seymour's Azusa Street Revival.[42]

The crowds of African-Americans and whites worshiping together at William Seymour's Azusa Street Mission set the tone for much of the early Pentecostal movement. During the period of 1906–1924, Pentecostals defied social, cultural and political norms of the time that called for racial segregation and the enactment of Jim Crow laws. The Church of God in Christ, the Church of God (Cleveland), the Pentecostal Holiness Church, and the Pentecostal Assemblies of the World were all interracial denominations before the 1920s. These groups, especially in the Jim Crow South were under great pressure to conform to segregation. Ultimately, North American Pentecostalism would divide into white and African-American branches. Though it never entirely disappeared, interracial worship within Pentecostalism would not reemerge as a widespread practice until after the civil rights movement.[43]

Women were vital to the early Pentecostal movement.[44] Believing that whoever received the Pentecostal experience had the responsibility to use it towards the preparation for Christ's second coming, Pentecostal women held that the baptism in the Holy Spirit gave them empowerment and justification to engage in activities traditionally denied to them.[45][46] The first person at Parham's Bible college to receive Spirit baptism with the evidence of speaking in tongues was a woman, Agnes Ozman.[45][47][48] Women such as Florence Crawford, Ida Robinson, and Aimee Semple McPherson founded new denominations, and many women served as pastors, co-pastors, and missionaries.[49] Women wrote religious songs, edited Pentecostal papers, and taught and ran Bible schools.[50] The unconventionally intense and emotional environment generated in Pentecostal meetings dually promoted, and was itself created by, other forms of participation such as personal testimony and spontaneous prayer and singing. Women did not shy away from engaging in this forum, and in the early movement the majority of converts and church-goers were female.[51] Nevertheless, there was considerable ambiguity surrounding the role of women in the church. The subsiding of the early Pentecostal movement allowed a socially more conservative approach to women to settle in, and, as a result, female participation was channeled into more supportive and traditionally accepted roles. Auxiliary women's organizations were created to focus women's talents on more traditional activities. Women also became much more likely to be evangelists and missionaries than pastors. When they were pastors, they often co-pastored with their husbands.[52]

The majority of early Pentecostal denominations taught Christian pacifism and adopted military service articles that advocated conscientious objection.[53]

Spread and opposition

Azusa participants returned to their homes carrying their new experience with them. In many cases, whole churches were converted to the Pentecostal faith, but many times Pentecostals were forced to establish new religious communities when their experience was rejected by the established churches. One of the first areas of involvement was the African continent, where, by 1907, American missionaries were established in Liberia, as well as in South Africa by 1908.[54] Because speaking in tongues was initially believed to always be actual foreign languages, it was believed that missionaries would no longer have to learn the languages of the peoples they evangelized because the Holy Spirit would provide whatever foreign language was required. (When the majority of missionaries, to their disappointment, learned that tongues speech was unintelligible on the mission field, Pentecostal leaders were forced to modify their understanding of tongues.)[55] Thus, as the experience of speaking in tongues spread, a sense of the immediacy of Christ's return took hold, and that energy would be directed into missionary and evangelistic activity. Early Pentecostals saw themselves as outsiders from mainstream society, dedicated solely to preparing the way for Christ's return.[45][56]

An associate of Seymour's, Florence Crawford, brought the message to the Northwest, forming what would become the Apostolic Faith Church—a Holiness Pentecostal denomination—by 1908. After 1907, Azusa participant William Howard Durham, pastor of the North Avenue Mission in Chicago, returned to the Midwest to lay the groundwork for the movement in that region. It was from Durham's church that future leaders of the Pentecostal Assemblies of Canada would hear the Pentecostal message.[57] One of the most well known Pentecostal pioneers was Gaston B. Cashwell (the "Apostle of Pentecost" to the South), whose evangelistic work led three Southeastern holiness denominations into the new movement.[58]

The Pentecostal movement, especially in its early stages, was typically associated with the impoverished and marginalized of America, especially African Americans and Southern Whites. With the help of many healing evangelists such as Oral Roberts, Pentecostalism spread across America by the 1950s.[59]

International visitors and Pentecostal missionaries would eventually export the revival to other nations. The first foreign Pentecostal missionaries were Alfred G. Garr and his wife, who were Spirit baptized at Azusa and traveled to India and later Hong Kong.[60] On being Spirit baptized, Garr spoke in Bengali, a language he did not know, and becoming convinced of his call to serve in India came to Calcutta with his wife Lilian and began ministering at the Bow Bazar Baptist Church.[61] The Norwegian Methodist pastor T. B. Barratt was influenced by Seymour during a tour of the United States. By December 1906, he had returned to Europe, and he is credited with beginning the Pentecostal movement in Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Germany, France and England.[62] A notable convert of Barratt was Alexander Boddy, the Anglican vicar of All Saints' in Sunderland, England, who became a founder of British Pentecostalism.[63] Other important converts of Barratt were German minister Jonathan Paul who founded the first German Pentecostal denomination (the Mülheim Association) and Lewi Pethrus, the Swedish Baptist minister who founded the Swedish Pentecostal movement.[64]

Through Durham's ministry, Italian immigrant Luigi Francescon received the Pentecostal experience in 1907 and established Italian Pentecostal congregations in the US, Argentina (Christian Assembly in Argentina), and Brazil (Christian Congregation of Brazil). In 1908, Giacomo Lombardi led the first Pentecostal services in Italy.[65] In November 1910, two Swedish Pentecostal missionaries arrived in Belem, Brazil and established what would become the Assembleias de Deus (Assemblies of God of Brazil).[66] In 1908, John G. Lake, a follower of Alexander Dowie who had experienced Pentecostal Spirit baptism, traveled to South Africa and founded what would become the Apostolic Faith Mission of South Africa and the Zion Christian Church.[67] As a result of this missionary zeal, practically all Pentecostal denominations today trace their historical roots to the Azusa Street Revival.[68] Eventually, the first missionaries realized that they definitely needed to learn the local language and culture, needed to raise financial support, and develop long-term strategies for the development of indigenous churches.[69]

The first generation of Pentecostal believers faced immense criticism and ostracism from other Christians, most vehemently from the Holiness movement from which they originated. Alma White, leader of the Pillar of Fire Church—a Holiness Methodist denomination, wrote a book against the movement titled Demons and Tongues in 1910. She called Pentecostal tongues "satanic gibberish" and Pentecostal services "the climax of demon worship".[70] Famous Holiness Methodist preacher W. B. Godbey characterized those at Azusa Street as "Satan's preachers, jugglers, necromancers, enchanters, magicians, and all sorts of mendicants". To Dr. G. Campbell Morgan, Pentecostalism was "the last vomit of Satan", while Dr. R. A. Torrey thought it was "emphatically not of God, and founded by a Sodomite".[71] The Pentecostal Church of the Nazarene, one of the largest holiness groups, was strongly opposed to the new Pentecostal movement. To avoid confusion, the church changed its name in 1919 to the Church of the Nazarene.[72]

A. B. Simpson's Christian and Missionary Alliance—a Keswickian denomination—negotiated a compromise position unique for the time. Simpson believed that Pentecostal tongues speaking was a legitimate manifestation of the Holy Spirit, but he did not believe it was a necessary evidence of Spirit baptism. This view on speaking in tongues ultimately led to what became known as the "Alliance position" articulated by A. W. Tozer as "seek not—forbid not".[72]

Early controversies

The first Pentecostal converts were mainly derived from the Holiness movement and adhered to a Wesleyan understanding of entire sanctification as a definite, instantaneous experience and second work of grace.[6] Problems with this view arose when large numbers of converts entered the movement from non-Wesleyan backgrounds, especially from Baptist churches.[73] In 1910, William Durham of Chicago first articulated the Finished Work, a doctrine which located sanctification at the moment of salvation and held that after conversion the Christian would progressively grow in grace in a lifelong process.[74] This teaching polarized the Pentecostal movement into two factions: Holiness Pentecostalism and Finished Work Pentecostalism.[8] The Wesleyan doctrine was strongest in the Apostolic Faith Church, which views itself as being the successor of the Azusa Street Revival, as well as in the Calvary Holiness Association, Congregational Holiness Church, Church of God (Cleveland), Church of God in Christ, Free Gospel Church and the Pentecostal Holiness Church; these bodies are classed as Holiness Pentecostal denominations.[75] The Finished Work, however, would ultimately gain ascendancy among Pentecostals, in denominations such as the Assemblies of God, which was the first Finished Work Pentecostal denomination.[9] After 1911, most new Pentecostal denominations would adhere to Finished Work sanctification.[76]

In 1914, a group of 300 predominately white Pentecostal ministers and laymen from all regions of the United States gathered in Hot Springs, Arkansas, to create a new, national Pentecostal fellowship—the General Council of the Assemblies of God.[77] By 1911, many of these white ministers were distancing themselves from an existing arrangement under an African-American leader. Many of these white ministers were licensed by the African-American, C. H. Mason under the auspices of the Church of God in Christ, one of the few legally chartered Pentecostal organizations at the time credentialing and licensing ordained Pentecostal clergy. To further such distance, Bishop Mason and other African-American Pentecostal leaders were not invited to the initial 1914 fellowship of Pentecostal ministers. These predominately white ministers adopted a congregational polity, whereas the COGIC and other Southern groups remained largely episcopal and rejected a Finished Work understanding of Sanctification. Thus, the creation of the Assemblies of God marked an official end of Pentecostal doctrinal unity and racial integration.[78]

Among these Finished Work Pentecostals, the new Assemblies of God would soon face a "new issue" which first emerged at a 1913 camp meeting. During a baptism service, the speaker, R. E. McAlister, mentioned that the Apostles baptized converts once in the name of Jesus Christ, and the words "Father, Son, and Holy Ghost" were never used in baptism.[79] This inspired Frank Ewart who claimed to have received as a divine prophecy revealing a nontrinitarian conception of God.[80] Ewart believed that there was only one personality in the Godhead—Jesus Christ. The terms "Father" and "Holy Ghost" were titles designating different aspects of Christ. Those who had been baptized in the Trinitarian fashion needed to submit to rebaptism in Jesus' name. Furthermore, Ewart believed that Jesus' name baptism and the gift of tongues were essential for salvation. Ewart and those who adopted his belief, which is known as Oneness Pentecostalism, called themselves "oneness" or "Jesus' Name" Pentecostals, but their opponents called them "Jesus Only".[81][8]

Amid great controversy, the Assemblies of God rejected the Oneness teaching, and many of its churches and pastors were forced to withdraw from the denomination in 1916.[82] They organized their own Oneness groups. Most of these joined Garfield T. Haywood, an African-American preacher from Indianapolis, to form the Pentecostal Assemblies of the World. This church maintained an interracial identity until 1924 when the white ministers withdrew to form the Pentecostal Church, Incorporated. This church later merged with another group forming the United Pentecostal Church International.[83] This controversy among the Finished Work Pentecostals caused Holiness Pentecostals to further distance themselves from Finished Work Pentecostals, who they viewed as heretical.[8]

1930–1959

While Pentecostals shared many basic assumptions with conservative Protestants, the earliest Pentecostals were rejected by Fundamentalist Christians who adhered to cessationism. In 1928, the World Christian Fundamentals Association labeled Pentecostalism "fanatical" and "unscriptural". By the early 1940s, this rejection of Pentecostals was giving way to a new cooperation between them and leaders of the "new evangelicalism", and American Pentecostals were involved in the founding of the 1942 National Association of Evangelicals.[84] Pentecostal denominations also began to interact with each other both on national levels and international levels through the Pentecostal World Fellowship, which was founded in 1947.

Some Pentecostal churches in Europe, especially in Italy and Germany, during the war were also victims of the Holocaust. Because of their tongues speaking their members were considered mentally ill, and many pastors were sent either to confinement or to concentration camps.[citation needed]

Though Pentecostals began to find acceptance among evangelicals in the 1940s, the previous decade was widely viewed as a time of spiritual dryness, when healings and other miraculous phenomena were perceived as being less prevalent than in earlier decades of the movement.[85] It was in this environment that the Latter Rain Movement, the most important controversy to affect Pentecostalism since World War II, began in North America and spread around the world in the late 1940s. Latter Rain leaders taught the restoration of the fivefold ministry led by apostles. These apostles were believed capable of imparting spiritual gifts through the laying on of hands.[86] There were prominent participants of the early Pentecostal revivals, such as Stanley Frodsham and Lewi Pethrus, who endorsed the movement citing similarities to early Pentecostalism.[85] However, Pentecostal denominations were critical of the movement and condemned many of its practices as unscriptural. One reason for the conflict with the denominations was the sectarianism of Latter Rain adherents.[86] Many autonomous churches were birthed out of the revival.[85]

A simultaneous development within Pentecostalism was the postwar Healing Revival. Led by healing evangelists William Branham, Oral Roberts, Gordon Lindsay, and T. L. Osborn, the Healing Revival developed a following among non-Pentecostals as well as Pentecostals. Many of these non-Pentecostals were baptized in the Holy Spirit through these ministries. The Latter Rain and the Healing Revival influenced many leaders of the charismatic movement of the 1960s and 1970s.[87]

1960–present

Before the 1960s, most non-Pentecostal Christians who experienced the Pentecostal baptism in the Holy Spirit typically kept their experience a private matter or joined a Pentecostal church afterward.[88] The 1960s saw a new pattern develop where large numbers of Spirit baptized Christians from mainline churches in the US, Europe, and other parts of the world chose to remain and work for spiritual renewal within their traditional churches. This initially became known as New or Neo-Pentecostalism (in contrast to the older classical Pentecostalism) but eventually became known as the Charismatic Movement.[89] While cautiously supportive of the Charismatic Movement, the failure of Charismatics to embrace traditional Pentecostal teachings, such as the prohibition of dancing, abstinence from alcohol and other drugs such as tobacco, as well as restrictions on dress and appearance following the doctrine of outward holiness, initiated an identity crisis for classical Pentecostals, who were forced to reexamine long held assumptions about what it meant to be Spirit filled.[90][91] The liberalizing influence of the Charismatic Movement on classical Pentecostalism can be seen in the disappearance of many of these taboos since the 1960s, apart from certain Holiness Pentecostal denominations, such as the Apostolic Faith Church, which maintain these standards of outward holiness. Because of this, the cultural differences between classical Pentecostals and charismatics have lessened over time.[92] The global renewal movements manifest many of these tensions as inherent characteristics of Pentecostalism and as representative of the character of global Christianity.[93]

Beliefs

Pentecostalism is an evangelical faith, emphasizing the reliability of the Bible and the need for the transformation of an individual's life through faith in Jesus.[31] Like other evangelicals, Pentecostals generally adhere to the Bible's divine inspiration and inerrancy—the belief that the Bible, in the original manuscripts in which it was written, is without error.[94] Pentecostals emphasize the teaching of the "full gospel" or "foursquare gospel". The term foursquare refers to the four fundamental beliefs of Pentecostalism: Jesus saves according to John 3:16; baptizes with the Holy Spirit according to Acts 2:4; heals bodily according to James 5:15; and is coming again to receive those who are saved according to 1 Thessalonians 4:16–17.[95]

Salvation

The central belief of classical Pentecostalism is that through the death, burial, and resurrection of Jesus Christ, sins can be forgiven and humanity reconciled with God.[96] This is the Gospel or "good news". The fundamental requirement of Pentecostalism is that one be born again.[97] The new birth is received by the grace of God through faith in Christ as Lord and Savior.[98] In being born again, the believer is regenerated, justified, adopted into the family of God, and the Holy Spirit's work of sanctification is initiated.[99]

Classical Pentecostal soteriology is generally Arminian rather than Calvinist.[100] The security of the believer is a doctrine held within Pentecostalism; nevertheless, this security is conditional upon continual faith and repentance.[101] Pentecostals believe in both a literal heaven and hell, the former for those who have accepted God's gift of salvation and the latter for those who have rejected it.[102]

For most Pentecostals there is no other requirement to receive salvation. Baptism with the Holy Spirit and speaking in tongues are not generally required, though Pentecostal converts are usually encouraged to seek these experiences.[103][104][105] A notable exception is Jesus' Name Pentecostalism, most adherents of which believe both water baptism and Spirit baptism are integral components of salvation.

Baptism with the Holy Spirit

Pentecostals identify three distinct uses of the word "baptism" in the New Testament:

- Baptism into the body of Christ: This refers to salvation. Every believer in Christ is made a part of his body, the Church, through baptism. The Holy Spirit is the agent, and the body of Christ is the medium.[106]

- Water baptism: Symbolic of dying to the world and living in Christ, water baptism is an outward symbolic expression of that which has already been accomplished by the Holy Spirit, namely baptism into the body of Christ.[107]

- Baptism with the Holy Spirit: This is an experience distinct from baptism into the body of Christ. In this baptism, Christ is the agent and the Holy Spirit is the medium.[106]

While the figure of Jesus Christ and his redemptive work are at the center of Pentecostal theology, that redemptive work is believed to provide for a fullness of the Holy Spirit of which believers in Christ may take advantage.[108] The majority of Pentecostals believe that at the moment a person is born again, the new believer has the presence (indwelling) of the Holy Spirit.[104] While the Spirit dwells in every Christian, Pentecostals believe that all Christians should seek to be filled with him. The Spirit's "filling", "falling upon", "coming upon", or being "poured out upon" believers is called the baptism with the Holy Spirit.[109] Pentecostals define it as a definite experience occurring after salvation whereby the Holy Spirit comes upon the believer to anoint and empower them for special service.[110][111] It has also been described as "a baptism into the love of God".[112]

The main purpose of the experience is to grant power for Christian service. Other purposes include power for spiritual warfare (the Christian struggles against spiritual enemies and thus requires spiritual power), power for overflow (the believer's experience of the presence and power of God in their life flows out into the lives of others), and power for ability (to follow divine direction, to face persecution, to exercise spiritual gifts for the edification of the church, etc.).[113]

Pentecostals believe that the baptism with the Holy Spirit is available to all Christians.[114] Repentance from sin and being born again are fundamental requirements to receive it. There must also be in the believer a deep conviction of needing more of God in their life, and a measure of consecration by which the believer yields themself to the will of God. Citing instances in the Book of Acts where believers were Spirit baptized before they were baptized with water, most Pentecostals believe a Christian need not have been baptized in water to receive Spirit baptism. However, Pentecostals do believe that the biblical pattern is "repentance, regeneration, water baptism, and then the baptism with the Holy Ghost". There are Pentecostal believers who have claimed to receive their baptism with the Holy Spirit while being water baptized.[115]

It is received by having faith in God's promise to fill the believer and in yielding the entire being to Christ.[116] Certain conditions, if present in a believer's life, could cause delay in receiving Spirit baptism, such as "weak faith, unholy living, imperfect consecration, and egocentric motives".[117] In the absence of these, Pentecostals teach that seekers should maintain a persistent faith in the knowledge that God will fulfill his promise. For Pentecostals, there is no prescribed manner in which a believer will be filled with the Spirit. It could be expected or unexpected, during public or private prayer.[118]

Pentecostals expect certain results following baptism with the Holy Spirit. Some of these are immediate while others are enduring or permanent. Most Pentecostal denominations teach that speaking in tongues is an immediate or initial physical evidence that one has received the experience.[119] Some teach that any of the gifts of the Spirit can be evidence of having received Spirit baptism.[120] Other immediate evidences include giving God praise, having joy, and desiring to testify about Jesus.[119] Enduring or permanent results in the believer's life include Christ glorified and revealed in a greater way, a "deeper passion for souls", greater power to witness to nonbelievers, a more effective prayer life, greater love for and insight into the Bible, and the manifestation of the gifts of the Spirit.[121]

Holiness Pentecostals, with their background in the Wesleyan-Holiness movement, historically teach that baptism with the Holy Spirit, as evidenced by glossolalia, is the third work of grace, which follows the new birth (first work of grace) and entire sanctification (second work of grace).[6][7][8]

While the baptism with the Holy Spirit is a definite experience in a believer's life, Pentecostals view it as just the beginning of living a Spirit-filled life. Pentecostal teaching stresses the importance of continually being filled with the Spirit. There is only one baptism with the Spirit, but there should be many infillings with the Spirit throughout the believer's life.[122]

Divine healing

Pentecostalism is a holistic faith, and the belief that Jesus is Healer is one quarter of the full gospel. Pentecostals cite four major reasons for believing in divine healing: 1) it is reported in the Bible, 2) Jesus' healing ministry is included in his atonement (thus divine healing is part of salvation), 3) "the whole gospel is for the whole person"—spirit, soul, and body, 4) sickness is a consequence of the Fall of Man and salvation is ultimately the restoration of the fallen world.[123] In the words of Pentecostal scholar Vernon L. Purdy, "Because sin leads to human suffering, it was only natural for the Early Church to understand the ministry of Christ as the alleviation of human suffering, since he was God's answer to sin ... The restoration of fellowship with God is the most important thing, but this restoration not only results in spiritual healing but many times in physical healing as well."[124] In the book In Pursuit of Wholeness: Experiencing God's Salvation for the Total Person, Pentecostal writer and Church historian Wilfred Graves Jr. describes the healing of the body as a physical expression of salvation.[125]

For Pentecostals, spiritual and physical healing serves as a reminder and testimony to Christ's future return when his people will be completely delivered from all the consequences of the fall.[126] However, not everyone receives healing when they pray. It is God in his sovereign wisdom who either grants or withholds healing. Common reasons that are given in answer to the question as to why all are not healed include: God teaches through suffering, healing is not always immediate, lack of faith on the part of the person needing healing, and personal sin in one's life (however, this does not mean that all illness is caused by personal sin).[127] Regarding healing and prayer Purdy states:

On the other hand, it appears from Scripture that when we are sick we should be prayed for, and as we shall see later in this chapter, it appears that God's normal will is to heal. Instead of expecting that it is not God's will to heal us, we should pray with faith, trusting that God cares for us and that the provision He has made in Christ for our healing is sufficient. If He does not heal us, we will continue to trust Him. The victory many times will be procured in faith (see Heb. 10:35–36; 1 John 5:4–5).[128]

Pentecostals believe that prayer and faith are central in receiving healing. Pentecostals look to scriptures such as James 5:13–16 for direction regarding healing prayer.[129] One can pray for one's own healing (verse 13) and for the healing of others (verse 16); no special gift or clerical status is necessary. Verses 14–16 supply the framework for congregational healing prayer. The sick person expresses their faith by calling for the elders of the church who pray over and anoint the sick with olive oil. The oil is a symbol of the Holy Spirit.[130]

Besides prayer, there are other ways in which Pentecostals believe healing can be received. One way is based on Mark 16:17–18 and involves believers laying hands on the sick. This is done in imitation of Jesus who often healed in this manner.[131] Another method that is found in some Pentecostal churches is based on the account in Acts 19:11–12 where people were healed when given handkerchiefs or aprons worn by the Apostle Paul. This practice is described by Duffield and Van Cleave in Foundations of Pentecostal Theology:

Many Churches have followed a similar pattern and have given out small pieces of cloth over which prayer has been made, and sometimes they have been anointed with oil. Some most remarkable miracles have been reported from the use of this method. It is understood that the prayer cloth has no virtue in itself, but provides an act of faith by which one's attention is directed to the Lord, who is the Great Physician.[131]

During the initial decades of the movement, Pentecostals thought it was sinful to take medicine or receive care from doctors.[132] Over time, Pentecostals moderated their views concerning medicine and doctor visits; however, a minority of Pentecostal churches continues to rely exclusively on prayer and divine healing. For example, doctors in the United Kingdom reported that a minority of Pentecostal HIV patients were encouraged to stop taking their medicines and parents were told to stop giving medicine to their children, trends that placed lives at risk.[133]

Eschatology

The last element of the gospel is that Jesus is the "Soon Coming King". For Pentecostals, "every moment is eschatological" since at any time Christ may return.[134] This "personal and imminent" Second Coming is for Pentecostals the motivation for practical Christian living including: personal holiness, meeting together for worship, faithful Christian service, and evangelism (both personal and worldwide).[135] Globally, Pentecostal attitudes to the End Times range from enthusiastic participation in the prophecy subculture to a complete lack of interest through to the more recent, optimistic belief in the coming restoration of God's kingdom.[136]

Historically, however, they have been premillennial dispensationalists believing in a pretribulation rapture.[137] Pre-tribulation rapture theology was popularized extensively in the 1830s by John Nelson Darby,[138] and further popularized in the United States in the early 20th century by the wide circulation of the Scofield Reference Bible.[139]

Spiritual gifts

Pentecostals are continuationists, meaning they believe that all of the spiritual gifts, including the miraculous or "sign gifts", found in 1 Corinthians 12:4–11, 12:27–31, Romans 12:3–8, and Ephesians 4:7–16 continue to operate within the Church in the present time.[140] Pentecostals place the gifts of the Spirit in context with the fruit of the Spirit.[141] The fruit of the Spirit is the result of the new birth and continuing to abide in Christ. It is by the fruit exhibited that spiritual character is assessed. Spiritual gifts are received as a result of the baptism with the Holy Spirit. As gifts freely given by the Holy Spirit, they cannot be earned or merited, and they are not appropriate criteria with which to evaluate one's spiritual life or maturity.[142] Pentecostals see in the biblical writings of Paul an emphasis on having both character and power, exercising the gifts in love.

Just as fruit should be evident in the life of every Christian, Pentecostals believe that every Spirit-filled believer is given some capacity for the manifestation of the Spirit.[143] The exercise of a gift is considered to be a manifestation of the Spirit, not of the gifted person, and though the gifts operate through people, they are primarily gifts given to the Church.[142] They are valuable only when they minister spiritual profit and edification to the body of Christ. Pentecostal writers point out that the lists of spiritual gifts in the New Testament do not seem to be exhaustive. It is generally believed that there are as many gifts as there are useful ministries and functions in the Church.[143] A spiritual gift is often exercised in partnership with another gift. For example, in a Pentecostal church service, the gift of tongues might be exercised followed by the operation of the gift of interpretation.

According to Pentecostals, all manifestations of the Spirit are to be judged by the church. This is made possible, in part, by the gift of discerning of spirits, which is the capacity for discerning the source of a spiritual manifestation—whether from the Holy Spirit, an evil spirit, or from the human spirit.[144] While Pentecostals believe in the current operation of all the spiritual gifts within the church, their teaching on some of these gifts has generated more controversy and interest than others. There are different ways in which the gifts have been grouped. W. R. Jones[145] suggests three categories, illumination (Word of Wisdom, word of knowledge, discerning of spirits), action (Faith, working of miracles and gifts of healings) and communication (Prophecy, tongues and interpretation of tongues). Duffield and Van Cleave use two categories: the vocal and the power gifts.

Vocal gifts

The gifts of prophecy, tongues, interpretation of tongues, and words of wisdom and knowledge are called the vocal gifts.[146] Pentecostals look to 1 Corinthians 14 for instructions on the proper use of the spiritual gifts, especially the vocal ones. Pentecostals believe that prophecy is the vocal gift of preference, a view derived from 1 Corinthians 14. Some teach that the gift of tongues is equal to the gift of prophecy when tongues are interpreted.[147] Prophetic and glossolalic utterances are not to replace the preaching of the Word of God[148] nor to be considered as equal to or superseding the written Word of God, which is the final authority for determining teaching and doctrine.[149]

Word of wisdom and word of knowledge

Pentecostals understand the word of wisdom and the word of knowledge to be supernatural revelations of wisdom and knowledge by the Holy Spirit. The word of wisdom is defined as a revelation of the Holy Spirit that applies scriptural wisdom to a specific situation that a Christian community faces.[150] The word of knowledge is often defined as the ability of one person to know what God is currently doing or intends to do in the life of another person.[151]

Prophecy

Pentecostals agree with the Protestant principle of sola Scriptura. The Bible is the "all sufficient rule for faith and practice"; it is "fixed, finished, and objective revelation".[152] Alongside this high regard for the authority of scripture is a belief that the gift of prophecy continues to operate within the Church. Pentecostal theologians Duffield and van Cleave described the gift of prophecy in the following manner: "Normally, in the operation of the gift of prophecy, the Spirit heavily anoints the believer to speak forth to the body not premeditated words, but words the Spirit supplies spontaneously in order to uplift and encourage, incite to faithful obedience and service, and to bring comfort and consolation."[144]

Any Spirit-filled Christian, according to Pentecostal theology, has the potential, as with all the gifts, to prophesy. Sometimes, prophecy can overlap with preaching "where great unpremeditated truth or application is provided by the Spirit, or where special revelation is given beforehand in prayer and is empowered in the delivery".[153]

While a prophetic utterance at times might foretell future events, this is not the primary purpose of Pentecostal prophecy and is never to be used for personal guidance. For Pentecostals, prophetic utterances are fallible, i.e. subject to error.[148] Pentecostals teach that believers must discern whether the utterance has edifying value for themselves and the local church.[154] Because prophecies are subject to the judgement and discernment of other Christians, most Pentecostals teach that prophetic utterances should never be spoken in the first person (e.g. "I, the Lord") but always in the third person (e.g. "Thus saith the Lord" or "The Lord would have...").[155]

Tongues and interpretation

A Pentecostal believer in a spiritual experience may vocalize fluent, unintelligible utterances (glossolalia) or articulate a natural language previously unknown to them (xenoglossy). Commonly termed "speaking in tongues", this vocal phenomenon is believed by Pentecostals to include an endless variety of languages. According to Pentecostal theology, the language spoken (1) may be an unlearned human language, such as the Bible claims happened on the Day of Pentecost, or (2) it might be of heavenly (angelic) origin. In the first case, tongues could work as a sign by which witness is given to the unsaved. In the second case, tongues are used for praise and prayer when the mind is superseded and "the speaker in tongues speaks to God, speaks mysteries, and ... no one understands him".[156]

Within Pentecostalism, there is a belief that speaking in tongues serves two functions. Tongues as the initial evidence of the third work of grace, baptism with the Holy Spirit,[6] and in individual prayer serves a different purpose than tongues as a spiritual gift.[156][157] All Spirit-filled believers, according to initial evidence proponents, will speak in tongues when baptized in the Spirit and, thereafter, will be able to express prayer and praise to God in an unknown tongue. This type of tongue speaking forms an important part of many Pentecostals' personal daily devotions. When used in this way, it is referred to as a "prayer language" as the believer is speaking unknown languages not for the purpose of communicating with others but for "communication between the soul and God".[158] Its purpose is for the spiritual edification of the individual. Pentecostals believe the private use of tongues in prayer (i.e. "prayer in the Spirit") "promotes a deepening of the prayer life and the spiritual development of the personality". From Romans 8:26–27, Pentecostals believe that the Spirit intercedes for believers through tongues; in other words, when a believer prays in an unknown tongue, the Holy Spirit is supernaturally directing the believer's prayer.[159]

Besides acting as a prayer language, tongues also function as the gift of tongues. Not all Spirit-filled believers possess the gift of tongues. Its purpose is for gifted persons to publicly "speak with God in praise, to pray or sing in the Spirit, or to speak forth in the congregation".[160] There is a division among Pentecostals on the relationship between the gifts of tongues and prophecy.[161] One school of thought believes that the gift of tongues is always directed from man to God, in which case it is always prayer or praise spoken to God but in the hearing of the entire congregation for encouragement and consolation. Another school of thought believes that the gift of tongues can be prophetic, in which case the believer delivers a "message in tongues"—a prophetic utterance given under the influence of the Holy Spirit—to a congregation.

Whether prophetic or not, however, Pentecostals are agreed that all public utterances in an unknown tongue must be interpreted in the language of the gathered Christians.[148] This is accomplished by the gift of interpretation, and this gift can be exercised by the same individual who first delivered the message (if he or she possesses the gift of interpretation) or by another individual who possesses the required gift. If a person with the gift of tongues is not sure that a person with the gift of interpretation is present and is unable to interpret the utterance themself, then the person should not speak.[148] Pentecostals teach that those with the gift of tongues should pray for the gift of interpretation.[160] Pentecostals do not require that an interpretation be a literal word-for-word translation of a glossolalic utterance. Rather, as the word "interpretation" implies, Pentecostals expect only an accurate explanation of the utterance's meaning.[162]

Besides the gift of tongues, Pentecostals may also use glossolalia as a form of praise and worship in corporate settings. Pentecostals in a church service may pray aloud in tongues while others pray simultaneously in the common language of the gathered Christians.[163] This use of glossolalia is seen as an acceptable form of prayer and therefore requires no interpretation. Congregations may also corporately sing in tongues, a phenomenon known as singing in the Spirit.

Speaking in tongues is not universal among Pentecostal Christians. In 2006, a ten-country survey by the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life found that 49 percent of Pentecostals in the US, 50 percent in Brazil, 41 percent in South Africa, and 54 percent in India said they "never" speak or pray in tongues.[105]

Power gifts

The gifts of power are distinct from the vocal gifts in that they do not involve utterance. Included in this category are the gift of faith, gifts of healing, and the gift of miracles.[164] The gift of faith (sometimes called "special" faith) is different from "saving faith" and normal Christian faith in its degree and application.[165] This type of faith is a manifestation of the Spirit granted only to certain individuals "in times of special crisis or opportunity" and endues them with "a divine certainty ... that triumphs over everything". It is sometimes called the "faith of miracles" and is fundamental to the operation of the other two power gifts.[166]

Trinitarianism and Oneness

During the 1910s, the Finished Work Pentecostal movement split over the nature of the Godhead into two camps – Trinitarian and Oneness.[8] The Oneness doctrine viewed the doctrine of the Trinity as polytheistic.[167]

The majority of Pentecostal denominations believe in the doctrine of the Trinity, which is considered by them to be Christian orthodoxy; these include Holiness Pentecostals and Finished Work Pentecostals. Oneness Pentecostals are nontrinitarian Christians, believing in the Oneness theology about God.[168]

In Oneness theology, the Godhead is not three persons united by one substance, but one God who reveals himself in three different modes. Thus, God relates himself to humanity as our Father within creation, he manifests himself in human form as the Son by virtue of his incarnation as Jesus Christ (1 Timothy 3:16), and he is the Holy Spirit (John 4:24) by way of his activity in the life of the believer.[169][170] Oneness Pentecostals believe that Jesus is the name of God and therefore baptize in the name of Jesus Christ as performed by the apostles (Acts 2:38), fulfilling the instructions left by Jesus Christ in the Great Commission (Matthew 28:19), they believe that Jesus is the only name given to mankind by which we must be saved (Acts 4:12).

The Oneness doctrine may be considered a form of Modalism, an ancient teaching considered heresy by the Roman Catholic Church and other trinitarian denominations. In contrast, Trinitarian Pentecostals hold to the doctrine of the Trinity, that is, the Godhead is not seen as simply three modes or titles of God manifest at different points in history, but is constituted of three completely distinct persons who are co-eternal with each other and united as one substance. The Son is from all eternity who became incarnate as Jesus, and likewise the Holy Spirit is from all eternity, and both are with the eternal Father from all eternity.[171]

Worship

Traditional Pentecostal worship has been described as a "gestalt made up of prayer, singing, sermon, the operation of the gifts of the Spirit, altar intercession, offering, announcements, testimonies, musical specials, Scripture reading, and occasionally the Lord's supper".[172] Russell P. Spittler identified five values that govern Pentecostal spirituality.[173] The first was individual experience, which emphasizes the Holy Spirit's personal work in the life of the believer. Second was orality, a feature that might explain Pentecostalism's success in evangelizing nonliterate cultures. The third was spontaneity; members of Pentecostal congregations are expected to follow the leading of the Holy Spirit, sometimes resulting in unpredictable services. The fourth value governing Pentecostal spirituality was "otherworldliness" or asceticism, which was partly informed by Pentecostal eschatology. The final and fifth value was a commitment to biblical authority, and many of the distinctive practices of Pentecostals are derived from a literal reading of scripture.[173]

Spontaneity is a characteristic element of Pentecostal worship. This was especially true in the movement's earlier history, when anyone could initiate a song, chorus, or spiritual gift.[174] Even as Pentecostalism has become more organized and formal, with more control exerted over services,[175] the concept of spontaneity has retained an important place within the movement and continues to inform stereotypical imagery, such as the derogatory "holy roller". The phrase "Quench not the Spirit", derived from 1 Thessalonians 5:19, is used commonly and captures the thought behind Pentecostal spontaneity.[176]

Prayer plays an important role in Pentecostal worship. Collective oral prayer, whether glossolalic or in the vernacular or a mix of both, is common. While praying, individuals may lay hands on a person in need of prayer, or they may raise their hands in response to biblical commands (1 Timothy 2:8). The raising of hands (which itself is a revival of the ancient orans posture) is an example of some Pentecostal worship practices that have been widely adopted by the larger Christian world.[177][178][179] Pentecostal musical and liturgical practice have also played an influential role in shaping contemporary worship trends, popularized by the leading producers of Christian music[180] from artists such as Chris Tomlin, Michael W. Smith, Zach Williams, Darlene Zschech, Matt Maher, Phil Wickham, Grace Larson, Don Moen and bands such as Hillsong Worship, Bethel Worship, Jesus Culture and Sovereign Grace Music.

Several spontaneous practices have become characteristic of Pentecostal worship. Being "slain in the Spirit" or "falling under the power" is a form of prostration in which a person falls backwards, as if fainting, while being prayed over.[181][182] It is at times accompanied by glossolalic prayer; at other times, the person is silent.[173] It is believed by Pentecostals to be caused by "an overwhelming experience of the presence of God",[183] and Pentecostals sometimes receive the baptism in the Holy Spirit in this posture.[173] Another spontaneous practice is "dancing in the Spirit". This is when a person leaves their seat "spontaneously 'dancing' with eyes closed without bumping into nearby persons or objects". It is explained as the worshipper becoming "so enraptured with God's presence that the Spirit takes control of physical motions as well as the spiritual and emotional being".[181] Pentecostals derive biblical precedent for dancing in worship from 2 Samuel 6, where David danced before the Lord.[173] A similar occurrence is often called "running the aisles". The "Jericho march" (inspired by Book of Joshua 6:1–27) is a celebratory practice occurring at times of high enthusiasm. Members of a congregation began to spontaneously leave their seats and walk in the aisles inviting other members as they go. Eventually, a full column forms around the perimeter of the meeting space as worshipers march with singing and loud shouts of praise and jubilation.[173][184] Another spontaneous manifestation found in some Pentecostal churches is holy laughter, in which worshippers uncontrollably laugh. In some Pentecostal churches, these spontaneous expressions are primarily found in revival services (especially those that occur at tent revivals and camp meetings) or special prayer meetings, being rare or non-existent in the main services.

Ordinances

Like other Christian churches, Pentecostals believe that certain rituals or ceremonies were instituted as a pattern and command by Jesus in the New Testament. Pentecostals commonly call these ceremonies ordinances. Many Christians call these sacraments, but this term is not generally used by Pentecostals and certain other Protestants as they do not see ordinances as imparting grace.[185] Instead the term sacerdotal ordinance is used to denote the distinctive belief that grace is received directly from God by the congregant with the officiant serving only to facilitate rather than acting as a conduit or vicar.

The ordinance of water baptism is an outward symbol of an inner conversion that has already taken place. Therefore, most Pentecostal groups practice believer's baptism by immersion. The majority of Pentecostals do not view baptism as essential for salvation, and likewise, most Pentecostals are Trinitarian and use the traditional Trinitarian baptismal formula. However, Oneness Pentecostals view baptism as an essential and necessary part of the salvation experience and, as non-Trinitarians, reject the use of the traditional baptismal formula. For more information on Oneness Pentecostal baptismal beliefs, see the following section on Statistics and denominations.

The ordinance of Holy Communion, or the Lord's Supper, is seen as a direct command given by Jesus at the Last Supper, to be done in remembrance of him. Pentecostal denominations, who traditionally support the temperance movement, reject the use of wine as part of communion, using grape juice instead.[186][187]

Certain Pentecostal denominations observe the ordinance of women's headcovering in obedience to 1 Corinthians 11:4–13.[188]

Foot washing is also held as an ordinance by some Pentecostals.[189] It is considered an "ordinance of humility" because Jesus showed humility when washing his disciples' feet in John 13:14–17.[185] Other Pentecostals do not consider it an ordinance; however, they may still recognize spiritual value in the practice.[190]

Statistics and denominations

According to various scholars and sources, Pentecostalism is the fastest-growing religious movement in the world;[191][192][193][194][195] this growth is primarily due to religious conversion to Pentecostal and Charismatic Christianity.[196][197] According to Pulitzer Center 35,000 people become Pentecostal or "Born again" every day.[198] According to scholar Keith Smith of Georgia State University "many scholars claim that Pentecostalism is the fastest growing religious phenomenon in human history",[199] and according to scholar Peter L. Berger of Boston University "the spread of Pentecostal Christianity may be the fastest growing movement in the history of religion".[199]

In 1995, David Barrett estimated there were 217 million "Denominational Pentecostals" throughout the world.[200] In 2011, a Pew Forum study of global Christianity found that there were an estimated 279 million classical Pentecostals, making 4 percent of the total world population and 12.8 percent of the world's Christian population Pentecostal.[201] The study found "Historically Pentecostal denominations" (a category that did not include independent Pentecostal churches) to be the largest Protestant denominational family.[202]

The largest percentage of Pentecostals are found in Sub-Saharan Africa (44 percent), followed by the Americas (37 percent)[203] and Asia and the Pacific (16 percent).[204] The movement is witnessing its greatest surge today in the global South, which includes Africa, Central and Latin America, and most of Asia.[205][206] There are 740 recognized Pentecostal denominations,[207] but the movement also has a significant number of independent churches that are not organized into denominations.[208]

Among the over 700 Pentecostal denominations, 240 are classified as part of Wesleyan, Holiness, or "Methodistic" Pentecostalism. Until 1910, Pentecostalism was universally Wesleyan in doctrine, and Holiness Pentecostalism continues to predominate in the Southern United States. Wesleyan Pentecostals teach that there are three crisis experiences within a Christian's life: conversion, sanctification, and Spirit baptism. They inherited the holiness movement's belief in entire sanctification.[6] According to Wesleyan Pentecostals, entire sanctification is a definite event that occurs after salvation but before Spirit baptism. This inward experience cleanses and enables the believer to live a life of outward holiness. This personal cleansing prepares the believer to receive the baptism in the Holy Spirit. Holiness Pentecostal denominations include the Apostolic Faith Church, Calvary Holiness Association, Congregational Holiness Church, Free Gospel Church, Church of God in Christ, Church of God (Cleveland, Tennessee), and the Pentecostal Holiness Church.[207][209][210] In the United States, many Holiness Pentecostal clergy are educated at the Heritage Bible College in Savannah, Georgia and the Free Gospel Bible Institute in Murrysville, Pennsylvania.[211][212]

After William H. Durham began preaching his Finished Work doctrine in 1910, many Pentecostals rejected the Wesleyan doctrine of entire sanctification and began to teach that there were only two definite crisis experiences in the life of a Christian: conversion and Spirit baptism. These Finished Work Pentecostals (also known as "Baptistic" or "Reformed" Pentecostals because many converts were originally drawn from Baptist and Presbyterian backgrounds) teach that a person is initially sanctified at the moment of conversion. After conversion, the believer grows in grace through a lifelong process of progressive sanctification. There are 390 denominations that adhere to the finished work position. They include the Assemblies of God, the Foursquare Gospel Church, the Pentecostal Church of God, and the Open Bible Churches.[207][209]

The 1904–1905 Welsh Revival laid the foundation for British Pentecostalism including a distinct family of denominations known as Apostolic Pentecostalism (not to be confused with Oneness Pentecostalism). These Pentecostals are led by a hierarchy of living apostles, prophets, and other charismatic offices. Apostolic Pentecostals are found worldwide in 30 denominations, including the Apostolic Church based in the United Kingdom.[207]

There are 80 Pentecostal denominations that are classified as Jesus' Name or Oneness Pentecostalism (often self identifying as "Apostolic Pentecostals").[207] These differ from the rest of Pentecostalism in several significant ways. Oneness Pentecostals reject the doctrine of the Trinity. They do not describe God as three persons but rather as three manifestations of the one living God. Oneness Pentecostals practice Jesus' Name Baptism—water baptisms performed in the name of Jesus Christ, rather than that of the Trinity. Oneness Pentecostal adherents believe repentance, baptism in Jesus' name, and Spirit baptism are all essential elements of the conversion experience.[213] Oneness Pentecostals hold that repentance is necessary before baptism to make the ordinance valid, and receipt of the Holy Spirit manifested by speaking in other tongues is necessary afterwards, to complete the work of baptism. This differs from other Pentecostals, along with evangelical Christians in general, who see only repentance and faith in Christ as essential to salvation. This has resulted in Oneness believers being accused by some (including other Pentecostals) of a "works-salvation" soteriology,[214] a charge they vehemently deny. Oneness Pentecostals insist that salvation comes by grace through faith in Christ, coupled with obedience to his command to be "born of water and of the Spirit"; hence, no good works or obedience to laws or rules can save anyone.[215] For them, baptism is not seen as a "work" but rather the indispensable means that Jesus himself provided to come into his kingdom. The major Oneness churches include the United Pentecostal Church International and the Pentecostal Assemblies of the World.

In addition to the denominational Pentecostal churches, there are many Pentecostal churches that choose to exist independently of denominational oversight.[208] Some of these churches may be doctrinally identical to the various Pentecostal denominations, while others may adopt beliefs and practices that differ considerably from classical Pentecostalism, such as Word of Faith teachings or Kingdom Now theology. Some of these groups have been successful in utilizing the mass media, especially television and radio, to spread their message.[216]

According to a denomination census in 2024, the Assemblies of God, the largest Pentecostal denomination in the world, has 450,106 churches and 86,143,293 members worldwide.[217] The other major international Pentecostal denominations are the Apostolic Church with 15,000,000 members,[218] the Church of God (Cleveland) with 36,000 churches and 7,000,000 members,[219] The Foursquare Church with 67,500 churches and 8,800,000 members,[220] and the United Pentecostal Church International with 45,521 church and 5,800,000 members.[221]

Among the censuses carried out by Pentecostal denominations published in 2020, those claiming the most members were on each continent:

In Africa, the Redeemed Christian Church of God,[222] with 14,000 churches and 5 million members.

In North America, the Assemblies of God USA with 12,986 churches and 1,810,093 members.[223]

In South America, the General Convention of the Assemblies of God in Brazil with 12,000,000 members.[224]

In Asia, the Indonesian Bethel Church with 5,000 churches and 3,000,000 members.[225]

In Europe, the Assemblies of God of France with 658 churches and 40,000 members.[226]

In Oceania, the Australian Christian Churches with 1,000 churches and 375,000 members.[227]

Assessment from the social sciences

Zora Neale Hurston

Zora Neale Hurston performed anthropological and sociological studies examining the spread of Pentecostalism, published posthumously in a collection of essays called The Sanctified Church.[228] According to scholar of religion Ashon Crawley, Hurston's analysis is important because she understood the class struggle that this seemingly new religiocultural movement articulated: "The Sanctified Church is a protest against the high-brow tendency in Negro Protestant congregations as the Negroes gain more education and wealth."[228] She stated that this sect was "a revitalizing element in Negro music and religion" and that this collection of groups was "putting back into Negro religion those elements which were brought over from Africa and grafted onto Christianity." Crawley would go on to argue that the shouting that Hurston documented was evidence of what Martinique psychoanalyst Frantz Fanon called the refusal of positionality wherein "no strategic position is given preference" as the creation of, the grounds for, social form.[229]

Rural Pentecostalism

Pentecostalism is a religious phenomenon more visible in the cities. However, it has attracted significant rural populations in Latin America, Africa, and Eastern Europe. Sociologist David Martin[230] has called attention on an overview on the rural Protestantism in Latin America, focusing on the indigenous and peasant conversion to Pentecostalism. The cultural change resulting from the countryside modernization has reflected on the peasant way of life. Consequently, many peasants – especially in Latin America – have experienced collective conversion to different forms of Pentecostalism and interpreted as a response to modernization in the countryside[231][232][233][234]

Rather than a mere religious shift from folk Catholicism to Pentecostalism, Peasant Pentecostals have dealt with agency to employ many of their cultural resources to respond development projects in a modernization framework[235][236][237]

Researching Guatemalan peasants and indigenous communities, Sheldon Annis[231] argued that conversion to Pentecostalism was a way to quit the burdensome obligations of the cargo-system. Mayan folk Catholicism has many fiestas with a rotation leadership who must pay the costs and organize the yearly patron-saint festivities. One of the socially-accepted ways to opt out those obligations was to convert to Pentecostalism. By doing so, the Pentecostal Peasant engage in a "penny capitalism". In the same lines of moral obligations but with different mechanism economic self-help, Paul Chandler[235] has compared the differences between Catholic and Pentecostal peasants, and has found a web of reciprocity among Catholics compadres, which the Pentecostals lacked. However, Alves[232] has found that the different Pentecostal congregations replaces the compadrazgo system and still provide channels to exercise the reciprocal obligations that the peasant moral economy demands.

Conversion to Pentecostalism provides a rupture with a socially disrupted past while allowing to maintain elements of the peasant ethos. Brazil has provided many cases to evaluate this thesis. Hoekstra[238] has found out that rural Pentecostalism more as a continuity of the traditional past though with some ruptures. Anthropologist Brandão[239] sees the small town and rural Pentecostalism as another face for folk religiosity instead of a path to modernization. With similar finding, Abumanssur[240] regards Pentecostalism as an attempt to conciliate traditional worldviews of folk religion with modernity.

Identity shift has been noticed among rural converts to Pentecostalism. Indigenous and peasant communities have found in the Pentecostal religion a new identity that helps them navigate the challenges posed by modernity.[241][242][243][244] This identity shift corroborates the thesis that the peasant Pentecostals pave their own ways when facing modernization.

Controversies and criticism

Various Christian groups have criticized the Pentecostal and charismatic movement for too much attention to mystical manifestations, such as glossolalia (which, for a believer, would be the obligatory sign of a baptism with the Holy Spirit); along with falls to the ground, moans and cries during worship services, as well as anti-intellectualism.[245]

A particularly controversial doctrine in the Evangelical Churches is that of the prosperity theology, which spread in the 1970s and 1980s in the United States, mainly through Pentecostals and charismatic televangelists.[246][247] This doctrine is centered on the teaching of Christian faith as a means to enrich oneself financially and materially through a "positive confession" and a contribution to Christian ministries.[248] Promises of divine healing and prosperity are guaranteed in exchange for certain amounts of donation.[249][250] Some pastors threaten those who do not tithe with curses, attacks from the devil and poverty.[251][252] The collections of offerings are multiple or separated in various baskets or envelopes to stimulate the contributions of the faithful.[253][254] The offerings and the tithe occupies a lot of time in some worship services.[254] Often associated with the mandatory tithe, this doctrine is sometimes compared to a religious business.[255][256][257] In 2012, the National Council of Evangelicals of France published a document denouncing this doctrine, mentioning that prosperity was indeed possible for a believer, but that this theology taken to the extreme leads to materialism and to idolatry, which is not the purpose of the gospel.[258][259] Pentecostal pastors adhering to prosperity theology have been criticized by journalists for their lavish lifestyle (luxury clothes, big houses, high end cars, private aircraft, etc.).[260]

In Pentecostalism, rifts accompanied the teaching of faith healing. In some churches, pricing for prayer against promises of healing has been observed.[231] Some pastors and evangelists have been charged with claiming false healings.[261][262] Some churches have advised their members against vaccination or other medicine, stating that it is for those weak in the faith and that with a positive confession, they would be immune from the disease.[263][264] Pentecostal churches that discourage the use of medicine have caused preventable deaths, sometimes leading to parents being sentenced to prison for the deaths of their children.[265] This position is not representative of most Pentecostal churches.[citation needed] "The Miraculous Healing", published in 2015 by the National Council of Evangelicals of France, describes medicine as one of the gifts given by God to humanity.[266][267] Churches and certain evangelical humanitarian organizations are also involved in medical health programs.[268][269][270]

In Pentecostalism, health and sickness is understood holistically. They are not just physical, concurrently, psychological and spiritual, i.e. diseases and despair are from evil forces; devil, sin. Through spiritual intimacy with ultimate divinity any illness can be healed. Today's Pentecostals accept biomedicine, but believe that divine intervention heals even where biomedicine fails. But critics argue that Pentecostal healers induce merely a placebo effect. In the anthropological view, the placebo effect mirrors that humans are a "socio- psycho -physical entity", thus through symbolic manipulation i.e. strong belief on divinity, rituals and miracles, it may induce an actual healing effect on the physical level.[271] In Pentecostalism, healing mainly is a spiritual experience.[272] Being worthy of having an intimacy with God (i.e. ability to confess, forgiveness) gives a cathartic effect[273] which leads to inner healing; accepting of self, healing from memories, which cleanse the root of emotional wounds and sufferings.[272] Divine healing also addresses socially born distresses; socio gender inequalities, racial hatreds which often emerge as physical ailments[273] by empowering patients.

Pentecostalism's divine healing practice is frequently dismissed as emotional or illogical, yet anthropological research reveals its profound cultural and social significance. Hefner[274] demonstrates how deeply rooted Pentecostal healing is in the social structures of countries like Indonesia. Healing techniques are not superstitious; rather, they are an expression of, and response to local power structures and social hierarchies. By functioning as tools for negotiating social roles and upholding communal ties, they show that these activities address genuine social issues and are not isolated from ordinary life. Meyer[275] shows how Pentecostal healing has a similar entanglement with broader cultural frameworks. Giving them a sense of empowerment dispels the notion that these activities are only a means of escape and group support. The focus on divine healing frequently reflects cultural perspectives on health and wellbeing, where social and spiritual dimensions are vital to comprehending and regulating health. Even while Pentecostals occasionally choose not to receive traditional medical care, this decision is influenced by a larger cultural framework that places a high importance on spiritual guidance and communal support.

Pentecostalism's doctrine belief in faith healing has been criticized for more than just its aversion to modern medicine, their tendency to attribute mental health conditions to demonic activity has also been questioned.[276] Faith healing has been the subject of numerous studies with a vast number of scholars aiming to either debunk or prove the effects of its use. One study however aimed rather to explore faith healing as a social construction. The study tracked the healing progress of over 100 participants. Throughout the study a significant number of participants went on to redefine their problem, such as one woman whose original problem was severe back pain; however at the conclusion of the study, she claims her troublesome relationship with her son was healed. Further the study found a correlation between those who redefine their issue and those who are more likely to claim they were healed. These findings suggest that these healings may not be a result of divine intervention. Glik[277] stated that "redefinitions may mirror therapeutic processes of self-discovery" meaning these acts of faith healing may simply be the result of self-growth or the result of the restructure of one's world view as they progress into a religious world view.

People

Forerunners

- William Boardman (1810–1886)

- Alexander Boddy (1854–1930)

- John Alexander Dowie (1848–1907)

- Henry Drummond (1786–1860)

- Edward Irving (1792–1834)

- Andrew Murray (1828–1917)

- Phoebe Palmer (1807–1874)

- Jessie Penn-Lewis (1861–1927)

- Evan Roberts (1878–1951)

- Albert Benjamin Simpson (1843–1919)

- Richard Green Spurling father (1810–1891) and son (1857–1935)

- James Haldane Stewart (1778–1854)

Leaders

- A. A. Allen (1911–1970) – Healing tent evangelist of the 1950s and 1960s

- Yiye Ávila (1925–2013) – Puerto Rican Pentecostal evangelist of the late 20th century

- Joseph Ayo Babalola (1904–1959) – Oke – Ooye, Ilesa revivalist in 1930, and spiritual founder of Christ Apostolic Church

- Reinhard Bonnke (1940–2019) – Evangelist

- William M. Branham (1909–1965) – American healing evangelist of the mid-20th century, generally acknowledged as initiating the post-World War II healing revival

- David Yonggi Cho (1936–2021) – Senior pastor and founder of the Yoido Full Gospel Church (Assemblies of God) in Seoul, South Korea, the world's largest congregation

- Jack Coe (1918–1956) – Healing tent evangelist of the 1950s

- Donnie Copeland (born 1961) – Pastor of Apostolic Church of North Little Rock, Arkansas, and Republican member of the Arkansas House of Representatives[278]

- Margaret Court (born 1942) – Tennis champion in the 1960s and 1970s and founder of Victory Life Centre in Perth, Australia; become a pastor in 1991

- Luigi Francescon (1866–1964) – Missionary and pioneer of the Italian Pentecostal Movement

- Donald Gee (1891–1966) – Early Pentecostal bible teacher in UK; "the apostle of balance"

- Benny Hinn (born 1952) – Evangelist

- Rex Humbard (1919–2007) – TV evangelist, 1950s–1970s

- George Jeffreys (1889–1962) – Founder of the Elim Foursquare Gospel Alliance and the Bible-Pattern Church Fellowship (UK)