Peel Regional Police

| Peel Regional Police | |

|---|---|

| |

| Motto | A Safer Community Together! |

| Agency overview | |

| Formed | 1974 |

| Jurisdictional structure | |

| Constituting instrument | |

| Operational structure | |

| Headquarters | 7150 Mississauga Road Mississauga, Ontario |

| Sworn members | 2,200 |

| Unsworn members | 875 |

| Elected officer responsible | |

| Agency executive |

|

| Divisions | 5 |

| Website | |

| www | |

The Peel Regional Police (PRP) provides policing services for Peel Region (excluding Caledon) in Ontario, Canada. It is the second largest municipal police service in the Greater Toronto Area in Ontario, and the third largest municipal force behind the Toronto Police Service, with 2,200 uniformed members and close to 875 support staff. The Peel Regional Police serve approximately 1.48 million citizens of Mississauga and Brampton, located immediately west and northwest of Toronto, and provides law enforcement services at Toronto Pearson International Airport (located in Mississauga) which annually sees 50 million travelers. Although it is part of the Region of Peel, policing for the Town of Caledon which is north of Brampton, is the responsibility of the Ontario Provincial Police (OPP).

The village of Snelgrove was once part of Caledon but is now within Brampton and the jurisdiction of Peel Regional Police. The PRP also patrols the section of Highway 409 between the Peel-Toronto boundary line (immediately west of Highway 427) and Pearson Airport. Policing of all other 400-series highways that pass through the region, including highways 401, 403, 410, and 427 as well as the QEW freeway and the 407 ETR toll highway, are the responsibility of the OPP.

History

The Peel Regional Police were established in tandem with creating the Regional Municipality of Peel on January 1, 1974. The former law enforcement organizations of Brampton, Mississauga, Chinguacousy, Port Credit and Streetsville got merged into a single law enforcement organization known as the Peel Regional Police Service.[1]

The Toronto Township Police Department was formed in January 1944 and was later renamed "Mississauga Police Department" in 1968. The Port Credit Police Department was founded with the township's incorporation in 1909. The Streetsville Police Department was formed in 1858. The Brampton Police Department dates to 1873 when it was created to replace policing from Chinguacousy. The Chinguacousy Township Police traces its roots back to 1853. Areas north of Mayfield Road (except Snelgrove) were transferred to the OPP when the northern half of Chinguacousy became part of Caledon (the southern half becoming part of Brampton) in 1974. All the police departments merged into the Peel Regional Police Service in 1974. As of 2020, the Peel Regional Police have approximately 2,200 officers and 875 civilian support staff. Since the creation of this police force, six deaths have been recorded, five from traffic accidents (the latest in March 2010) and one from a stabbing in 1984.[2]

Governance

The civilian Peel Regional Police Services Board governs the police service.[3]The Board’s membership consists of three provincial appointees, a citizen appointee, and three others including the Mayors of Brampton and Mississauga (presently vacant due to resignation by the Mayor of Mississauga), and the Regional Council Chair. The council heads, as Board Chair and Vice Chair, are selected from among the other board members.

Command structure

The Peel Regional Police divide the region into five divisions. Major police stations are located in each division which smaller community police stations support. These provide residents with services to deal with traffic complaints, neighborhood disputes, minor thefts, community issues, landlord-tenant disputes, found property, and doubts or questions related to policing in the community.

11 Division

Commanded by Superintendent David Kennedy

- 3030 Erin Mills Parkway, Mississauga

12 Division

Commanded by Superintendent Robert Higgs

- 4600 Dixie Road, Mississauga

The Marine Unit at 135 Lakefront Promenade is located in this division. The unit is responsible for 105 square kilometers of waterways, including Lake Ontario and rivers that run in the region using 3 boats. It was created in 1974 and inherited 1 boat from the Port Credit Police Department.[4]

21 Division

Commanded by Superintendent Navdeep Chinzer

- 10 Peel Centre Drive, Suite C, Brampton

22 Division

Commanded by Superintendent Sean Gormley

- 7750 Hurontario Street, Brampton

Community divisions

- Square One, 100 City Centre Drive

- Malton, 7205 Goreway Drive

- Cassie Campbell, 1050 Sandalwood Parkway West

Airport division

Currently commanded by Superintendent Robert Higgs, the airport division was established in 1997 following the departure of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP). It consists of plainclothes officers, uniformed officers, unsworn staff, and the tactical unit at 2951 Convair Drive, Mississauga.

Headquarters

- 7150 Mississauga Road, Mississauga

Rank structure

| Rank | Special constables | |

|---|---|---|

| Special constable supervisor | Special constable | |

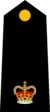

| Insignia

(slip-on) |

|

|

| Shirt color | Light blue | |

Uniform

As of January 2008, front-line officers wear dark navy blue shirts, cargo pants with a red stripe, and boots. Winter jackets are either black or reflective orange and yellow with the word police in white and blue at the back. Hats are standard forage caps with a red band. Yukon hats or embroidered toques are worn in the winter. Frontline officers wear dark-navy shirts, V-neck sweaters (optional during cold weather months), and side-pocket patrol pants ("cargo pants") with a red stripe (ranks of sergeant and higher wear a black stripe down their pant leg in place of red); and officers wear dark-navy rank slip-ons on the epaulets of their shirts, sweaters, and jackets with embroidered Canadian flags and badge numbers (in white) beneath on each (rank insignia above the flag for ranks above constable). Senior officers wear white shirts, dark navy pants (no side pocket) with a black stripe and dark navy jackets. Dark-navy V-neck sweaters are also worn. Senior officers wear gold collar brass (on the collar of their shirts) and dark-navy rank slip-ons on the epaulets of their shirts, sweaters, and jackets with embroidered Canadian flags, no badge numbers, and applicable rank insignia above the flag.

The external carriers (body armor) officers wear are black with silver police on the back and an embroidered patch over the right pocket with the badge number embroidered in white. This is the only uniform item that is black. On dark navy V-neck sweaters, an embroidered patch is worn on the left chest with police in white. Officers' standard headdress is the forage (or peak) cap; the cap is dark navy with a black peak, red band, and silver cap badge (gold cap badge for senior officers). An optional Yukon hat (artificial fur hat) or uniform toque can be worn in the winter. Officers of the Sikh faith are permitted to wear uniform turbans (dark navy blue with red stripe and cap badge). The shoulder flash (embroidered patch) worn on each arm by officers ranked constable through staff sergeant has a white border, white lettering, black background, and colored seal of the Regional Municipality of Peel. The shoulder flash worn on each arm by senior officers (higher ranks) has a gold border, gold lettering, black background, and colored seal of the Regional Municipality of Peel.

Fleet

The Peel Regional Police Service has a fleet of over 500 vehicles including:

- Ford Taurus Police Interceptor Sedans

- Dodge Charger (LX) cruisers (marked & unmarked)

- Harley-Davidson FL motorcycles (traffic services unit)

- Chevrolet Tahoe SUV (airport enforcement)

- Ford Explorer SUV (duty inspector & sergeant)

- Chevrolet Suburban SUV, Chevrolet Express & Ram Express (tactical rescue unit)

- Ford Escape Hybrid SUV (media relations)

- Terradyne Armored Vehicles Inc. GURKHA with Patriot MARS (mobile adjustable ramp system) - tactical truck

- Marine 1 - 40-foot (12 m) Hike Metal, twin diesel powered/twin propeller aluminum-hulled motor vessel powered by two 310 horsepower Volvo Penta diesel engines

- Marine 2 - 26-foot (7.9 m) 2004 Zodiac Hurricane, 7.5-meter rigid hull inflatable boat powered by twin 150 horsepower (110 kW) outboard motors (two Yamaha 150 hp four-stroke outboard engines, 380 liters)

- Marine 3 – 18-foot aluminum boat with 25 hp outboard motor

- 16-foot aluminum boat - from Port Credit Police in 1974; retired

- Trek Bicycle Corporation mountain hardtail 3700 mountain bikes

- T3 Motion, Inc. electric vehicles (airport enforcement)

- Ford F350 paddy wagon (court services)

- Dodge Magnum (traffic enforcement)

All marked vehicles are painted white with three blue stripes, a change from the yellow standard used by GTA forces in the 1980s. In 2007, Peel Police spearheaded a campaign to amend provincial law to equip police cruisers with blue and red lights and deployed the first such cruiser in Ontario. As of 2008, new cruisers sport a single blue stripe. The force's logo moves forward along the stripe with the motto and phone number on the rear back door. Traffic enforcement has several vehicles that are not marked in the way described above. These vehicles are painted in a solid color, like most civilian vehicles, with the words Peel Regional Police applied in a semi-reflective decal in the same color as the vehicles' paint. Examples are cherry decals on red paint or charcoal decals on black paint.

Weapons

Uniform patrol

- SIG Sauer P320 9mm sidearm for all officers. Ammunition selected for these new firearms were Speer Gold Dot jacked hollow points.

- Smith & Wesson M&P .40 S&W caliber pistol [5]

- Smith & Wesson 4046 .40 S&W pistol (phased out)

- Remington 870 shotgun (supervisors) 12 gauge

- Ruger PC40 police carbine (supervisors). 40 S&W (phased out)

- Colt Canada C8 police carbine (supervisors) and qualified officers who have completed the patrol carbine course

Airport division & tactical rescue unit

- Heckler & Koch Mk.23 .45 ACP (phased out)

- Smith & Wesson M&P .40 S&W caliber pistol

- Heckler & Koch MP5 9mm Para

- Heckler & Koch MP7 4.7x33mm

- Colt Canada C8 assault rifles 5.56×45mm NATO

- FN FAL para carbine 7.62×51mm NATO

- Remington 870 shotgun 12 gauge

- Remington 700 sniper rifle .308 Win

- Barrett M82-A1 sniper rifle .50 BMG

Units

Traffic enforcement

- Regional breath

- Regional traffic

Investigation

- Divisional Criminal Investigation Bureau

- Homicide & Missing Persons Bureau

- Intimate partner violence

- Special victims

- Central robbery bureau

- Fraud bureau

- Major drugs & vice

- Street crimes

- Guns & gangs

- Major Collision bureau

- Commercial Auto Crime Bureau

- Internet child exploitation (I.C.E.)

- Tech crimes

- Forensic identification services

- Offenders management

Special

- Dive team

- Tactical response

- K-9

- Marine

- Training & Recruiting

Community support

- Divisional neighborhood policing

- Family violence

- Internal affairs

- Auxiliary (auxiliary constable) - established in 1989[6] and has about 100 members. Members caps have a red-black Battenburg band instead of the solid red used for sworn members [7]

- Community liaison office

- Crime prevention/alarm program

- Diversity relations

- Drug Education

- Labor Liaison

Awards

Peel Regional Police members are involved in fundraising for a variety of charities and community causes. They have annually raised over $1,000,000 for the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation and $140,000 through the "Cops for Cancer" program. They are also one of the region's largest donors to the United Way. Members of the force are involved in public service and volunteering throughout the community.

- (1995) won the Webber Seavey Award for quality in law enforcement sponsored by the International Association of Chiefs of Police, and Motorola. The award was made for the development of a process that helps abused children through the justice system and into treatment with minimal personal trauma. They were also awarded the Certificate of Merit by the National Quality Institute's "Canada Awards of Excellence" program.

- (1994) accredited by the Commission on Accreditation for Law Enforcement Agencies (CALEA), the first police service in Ontario to receive this distinction and the fifth in Canada.[8]

Misconduct allegations and convictions

2016 lawsuit against former Peel police chief, Jennifer Evans

Jennifer Evans and the Peel Police Service faced a 21 million dollar lawsuit alleging that they unlawfully interfered in the operation of the special investigations unit.[9][10][11] Previously, Evans had faced numerous calls for resignation after refusing to stop carding and implementing body worn cameras for all the frontline police officers.[12][13]

Other incidents

- (2020) Three Peel Police officers shot and killed Ejaz Ahmed Choudry after his daughter called a non-emergency ambulance to conduct a wellness check.[14] Choudry suffered from schizophrenia and was alone in his apartment unit.[14] Police denied Choudry's family's offer of help to deescalate the situation.[14] Three police officers entered the apartment unit through the balcony of the apartment and fired a taser and plastic projectiles at Choudry but without effect. Then one of the officers shot and killed him.[14] The SIU began a probe into the officers' actions, although the family has called for an independent public inquiry to be done. Three of the officers were cleared by the SIU.

- (2020) Peel Police officers shot Chantelle Krupka once on the porch of her house, after shooting her with a taser. Police were responding to a domestic call at Krupka's house and allegedly shot Krupka when she was lying on the ground. The coach officer supervising the junior officer, is now a lead media officer for the service, Cst. Tyler Bell-Morena.[15] Officer Valerie Briffa who shot Krupka, resigned from the force after the incident and was later charged with criminal negligence causing bodily harm, assault with a weapon and careless use of a firearm. She is now a successful trainer for a major law firm at Vancouver.[16][17]

- (2019) Peel Police officers were responding to a noise complaint and a report of a suspicious male causing a disturbance. The SIU investigated the death of Clive Mensah who was tasered by police. The outcome of the investigation was unknown.

- (2019) Constable David Chilicki was arrested and charged with assault and mischief that stemmed from an off-duty incident involving a female. He was suspended with pay.

- (2017) Constable Noel Santiago of 22 Division was arrested, charged, and suspended from duty for defrauding the police services benefits provider.

- (2017) A Brampton Superior Court found constables Richard Rerrie, Damien Savino, Mihai "Mike" Muresan, and Sergeant Emmanuel "Manny" Pinheiro perjured themselves at a suspect's trial to cover up the fact that they stole a Tony Montana statue from his downtown Toronto storage locker after his arrest. There was also video surveillance of this theft.

- (2017) Constable Donald Malott was involved in a domestic dispute with his wife. The OPP responded and charged him with careless storage of a firearm. He was accused of having several loaded firearms all over his home improperly stored. He was found guilty and was demoted to 2nd class constable.

- (2016) Peel Police handcuffed a six-year-old Black girl and restrained her on her stomach for 30 minutes at her Mississauga school. In March 2020, the tribunal determined that the police officers had racially discriminated against the girl and that their actions were a "clear overreaction".[18] In January 2021, damages were set at $35,000.[19]

- (2016) Constable Ryan Freitas caused a serious motor vehicle collision that seriously injured an innocent elderly woman. The officer was responding to a radio call, and as he approached the intersection of Boulevard Drive and Great Lakes Drive, he failed to stop for the red light and collided violently with the woman. The woman suffered several broken bones. He was deemed at fault, disciplined, and had to work several days without pay. For the clean-up crew that had to clean the road.

- (2015) Constable Lyndon Locke did not face criminal charges after he pleaded guilty to discreditable conduct over sexual assault and utter death threats allegations, instead he was only "docked pay"[20]

- (2008) Constable Roger Yeo was accused of stalking young girls while off-duty in the summer and fall of 2005. During the investigation into the stalking allegations, Yeo said he had used steroids while on the job and claimed other officers had also done so. This prompted Chief Mike Metcalf to launch an investigation into steroid use in the force.[21] Yeo was found guilty of discreditable conduct on April 29, 2008, and was suspended with pay. Yeo resigned on a date before his hearing, and all ongoing disciplinary proceedings were stayed.[22][23]

- (2006) A $9.5 million lawsuit was filed by a police officer, Constable Duane Simon, an 18-year veteran of the Toronto Police Service, alleging false imprisonment, abuse of public office, injurious falsehoods, negligent investigation, and breach of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms after he had been arrested and charged with assaulting of a female peel police officer.

- (2006) A $3.6 million lawsuit was filed by the parents of three Brampton teens alleging seven off-duty officers attacked them without cause in the fall of 2005 after one of the teens crashed his bicycle into a car owned by one of the men. The suit was settled out of court in June 2006.

- (2006) A $12 million suit was filed by Orlando Canizalez and Richard Cimpoesu who claim that they were roughed up by off-duty police officers on 28 August 2006 after refusing to give up their videotape of officers partying behind a strip mall. Fourteen officers have been charged under the Police Services Act of Ontario with offenses ranging from discreditable conduct to neglect of duty. Ten other officers have been disciplined for their roles in the incident. Of these, two officers were demoted to lower ranks, while others were suspended with pay from four to nine days. The lawsuit filed by the two men was pending.

- (2006) A $14.6 million lawsuit was filed by former Toronto Argonaut football player Orlando Bowen, who said he was assaulted and falsely arrested on 26 March 2004 by two undercover officers outside a Mississauga nightclub. Bowen was tried and acquitted of drug possession in 2005, claiming the officers had planted drugs on him. The judge in the case described the testimony of the officers involved as "incredible and unworthy of belief". The Crown prosecutor attempted to have the charges against Bowen withdrawn before a verdict was rendered after Constable Sheldon Cook, a 14-year veteran of the force, was charged on 18 November 2005 by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) with drug possession and drug trafficking. RCMP officers tracked a shipment of cocaine from Pearson International Airport to Cook's home in Cambridge where they found 15 kilograms of the drug with a street value of more than $500,000.[24]

Shooting death of Michael Wade Lawson

On 8 December 1988, 17-year-old Michael Wade Lawson was shot to death by two Peel Regional Police Constables. Anthony Melaragni No. 1192 and Darren Longpre No. 1139 were both charged with second-degree murder and aggravated assault after a preliminary hearing; a jury later acquitted both. The officers claimed that the stolen vehicle driven by Lawson was approaching the officers head-on in a threatening manner, and they then discharged their firearms.[25]

An autopsy conducted by the Ontario Coroner's Office showed that the unarmed teenager was struck by a hollow-point bullet to the back of the head. This type of bullet was considered illegal at the time, as hollow-point bullets were not authorized for use by police officers in Ontario. Shortly after Lawson's death, the Attorney General of Ontario and the black Canadian community pressured the government to establish a race relations and policing task force. This task force made several recommendations, and the result led the provincial government to create a law enforcement oversight agency known as the Special Investigations Unit (S.I.U.) for conducting investigations and laying charges against police officers for their actions resulting in a civilian's injury or death.[25]

Public complaints

The Peel Regional Police Public Complaints Investigation Bureau (PCIB) investigates all complaints made by the public regarding the actions and services provided by police officers. PCIB is a branch of the Professional Standards Bureau.

In 2005, 158 public complaints were filed:

- Two resulted in informal discipline.

- One resulted in charges under the Ontario Police Services Act.

- None resulted in charges under the Criminal Code.

- 155 were withdrawn by the complainants, resolved informally, or ruled invalid as they exceeded the time limit, or the complainant was not directly affected.

In 2004, 180 public complaints were filed:

- Three resulted in informal discipline.

- None resulted in charges under the Ontario Police Services Act.

- None resulted in charges under the Criminal Code.

- 177 were withdrawn by the complainants, resolved informally, or ruled invalid as they exceeded the time limit, or the complainant was not directly affected.

See also

References

- ^ "Our History". Peel Regional Police. Retrieved May 23, 2020.

- ^ "Lest We Forget Fallen Officers". Peel Regional Police. 27 June 2018. Retrieved May 23, 2020.

- ^ https://www.peelpoliceboard.ca/

- ^ "Marine Unit". Peel Regional Police. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016.

- ^ "Smith & Wesson Holding Corporation Reports Record Quarterly Sales". Smith & Wesson Holding Corporation. March 8, 2006. Archived from the original on November 12, 2006.

- ^ "40th Anniversary: Time Capsule Tuesday - Monthly Listing". Peel Regional Police. Archived from the original on December 24, 2014.

- ^ "Auxiliary Police". Peel Regional Police. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- ^ "Peel Regional Police - History". Anabela Guerreiro. Archived from the original on August 22, 2007.

- ^ Fraser, Laura (December 9, 2016). "Peel police Chief Jennifer Evans named in $21M lawsuit alleging she interfered in shooting probe". CBC News. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- ^ Gallant, Jacques (December 9, 2016). "Victim of police shooting sues Peel chief and others for $21 million". The Toronto Star. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- ^ Rosella, Louie (April 21, 2016). "Innocent bystander shot by Peel cop files private criminal charge". mississauga.com. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- ^ Grewal, San (October 4, 2016). "Peel residents at meeting call for the police chief to resign". The Toronto Star. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- ^ Kan, Alan (September 19, 2016). ""No Body Cameras" One of the Topics Discussed at Peel Police Meeting in Mississauga". insauga.com. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Wilson, Codi; Aguilar, Bryann (2020-06-21). "Family of a 62-year-old man fatally shot by police in Mississauga, Ont. calls for public inquiry". Toronto. CTV News. Retrieved 2020-06-22.

- ^ "'Why did you shoot me?' A Black mother seeks answers from Peel police". thestar.com. 2020-06-23. Retrieved 2020-06-24.

- ^ "Peel officer charged in shooting of Black mom was months into job". thestar.com. 2020-07-16. Retrieved 2020-07-21.

- ^ "Ex-Peel constable charged by SIU after Mississauga mom shot on Mother's Day". CP24. 2020-07-16. Retrieved 2020-07-21.

- ^ "Race was a factor in handcuffing of the 6-year-old black girl in Mississauga school, tribunal says". CBC News. March 3, 2020.

- ^ "Peel police ordered to pay $35,000 in damages for handcuffing six-year-old Black girl". Globe and Mail. Canadian Press. January 7, 2021. Retrieved January 8, 2021.

- ^ Newport, Ashley (October 21, 2016). "Peel Police Officer Docked Pay for Sexual Harassment Incident in Mississauga". insauga.com. Retrieved May 25, 2020.

- ^ Boesveld, Sarah (January 29, 2008). "Peel officer admits to using steroids on the job". The Toronto Star. Retrieved May 25, 2020.

- ^ Stewart, John (February 3, 2009). "Disgraced cop resigns". Mississauga.com. Archived from the original on July 28, 2011.

- ^ "Peel Police - Resignation of Peel Police Officer Roger Yeo". Peel Regional Police. February 3, 2009. Archived from the original on July 27, 2011.

- ^ "National: Ex-Argo sues Peel Police over arrest". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on 2009-02-11.

- ^ a b "Part III: Anti-Black Racism in Canada's Criminal Justice System". African Canadian Legal Clinic. July 2002. Archived from the original on May 5, 2006.