Greek Civil War

| Greek Civil War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Cold War | |||||||

QF 25 pounder gun of the Hellenic Army during the Civil War | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

Supported by: |

Supported by: | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

15,000–20,000 Slav Macedonians 2,000–3,000 Pomaks 130–150 Chams[3] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

20,128 captured (Hellenic Army claim) | |||||||

|

80,000[6]–158,000 total killed[7][8][9][10] 1,000,000 temporarily relocated during the war[11] | |||||||

The Greek Civil War (Greek: Eμφύλιος Πόλεμος, romanized: Emfýlios Pólemos) took place from 1946 to 1949. The conflict, which erupted shortly after the end of World War II, consisted of a Communist-led uprising against the established government of the Kingdom of Greece. The rebels declared a people's republic, the Provisional Democratic Government of Greece, which was governed by the Communist Party of Greece (KKE) and its military branch, the Democratic Army of Greece (DSE). The rebels were supported by Albania and Yugoslavia. With the support of the United Kingdom and the United States, the Greek government forces ultimately prevailed.

The war had its roots in divisions within Greece during World War II between the Communist-dominated left-wing resistance organisation, the EAM-ELAS, and loosely-allied anti-communist resistance forces. It later escalated into a major civil war between the Greek state and the Communists. The DSE was defeated by the Hellenic Army.[12]

The war resulted from a highly polarized struggle between left and right ideologies that started when each side targeted the power vacuum resulting from the end of Axis occupation (1941–1944) during World War II. The struggle was the first proxy conflict of the Cold War and represents the first example of postwar involvement on the part of the Allies in the internal affairs of a foreign country,[13] an implementation of the containment policy suggested by US diplomat George F. Kennan in his Long Telegram of February 1946.[14] The Greek royal government in the end was funded by the United States (through the Truman Doctrine of 1947 and the Marshall Plan of 1948) and joined NATO (1952), while the insurgents were demoralized by the bitter split between the Soviet Union's Joseph Stalin, who wanted to end the war, and Yugoslavia's Josip Broz Tito, who wanted it to continue.[15]

Background: 1941–1944

Origins

While Axis forces approached Athens in April 1941, King George II and his government escaped to Egypt, where they proclaimed a government-in-exile. At the same time, the Germans set up a collaborationist government in Athens, which lacked legitimacy and support.

The power vacuum that the occupation created was filled by several resistance movements that ranged from monarchist to Communist in ideology. Resistance was born first in eastern Macedonia and Thrace, where Bulgarian troops occupied Greek territory. Soon large demonstrations were organized in many cities by the Defenders of Northern Greece (YVE), a patriotic organization. However, the largest group to emerge was the National Liberation Front (EAM), founded on 27 September 1941 by representatives of four left-wing parties.

Although controlled by the Communist Party of Greece (KKE), the organization had democratic republican rhetoric.[citation needed] Its military wing, ELAS was founded in February 1942. Aris Velouchiotis, a member of KKE's Central Committee, was nominated Chief (Kapetanios) of the ELAS High Command. The military chief, Stefanos Sarafis, was a colonel in the prewar Greek army who had been dismissed during the Metaxas regime for his views. The political chief of EAM was Vasilis Samariniotis (nom de guerre of Andreas Tzimas).

The Organization for the Protection of the People's Struggle (OPLA) was founded as EAM's security militia, operating mainly in the occupied cities and most particularly Athens. A small Greek People's Liberation Navy (ELAN) was created, operating mostly around the Ionian Islands and some other coastal areas. Other Communist-aligned organizations were present, including the National Liberation Front (NOF), composed mostly of Slavic Macedonians in the Florina region. They would later play a critical role in the civil war.[16][17] The two other large resistance movements were the National Republican Greek League (EDES), led by republican former army officer Colonel Napoleon Zervas, and the social-liberal EKKA, led by Colonel Dimitrios Psarros.

Guerrilla control over rural areas

The Greek landscape was favourable to guerrilla operations, and by 1943, the Axis forces and their collaborators were in control only of the main towns and connecting roads, leaving the mountainous countryside to the resistance.[citation needed] EAM-ELAS in particular controlled most of the country's mountainous interior, while EDES was limited to Epirus and EKKA to eastern Central Greece.[citation needed] By early 1944, ELAS could call on nearly 25,000 fighters, with another 80,000 working as reserves or logistical support. EDES had roughly 10,000 members, and EKKA had under 10,000.[citation needed]

Ioannis Rallis, the Prime Minister of the collaborationist government sought to combat the rising influence of the EAM, and was fearful of an eventual takeover after the German defeat. In 1943, he authorised the creation of paramilitary forces, known as the Security Battalions. Numbering 20,000 at their peak in 1944, composed mostly of local fascists, convicts, sympathetic prisoners of war, and forcibly impressed conscripts, they operated under German command in Nazi security warfare operations and soon achieved a reputation for brutality.

First conflicts: 1943–1944

As the end of the war approached, the British Foreign Office, fearing a possible Communist upsurge, observed with displeasure the transformation of ELAS into a large-scale conventional army more and more out of Allied control. After the September 8, 1943, Armistice with Italy, ELAS seized control of Italian garrison weapons in the country. In response, the Western Allies began to favor rival anti-Communist resistance groups. They provided them with ammunition, supplies, and logistical support as a way of balancing ELAS's increasing influence. In time, the flow of weapons and funds to ELAS stopped altogether, and rival EDES received the bulk of the Allied support.

In mid-1943 the animosity between ELAS and the other movements erupted into armed conflict. The Communists, and EAM and EDS, accused each other of being 'traitors' and 'collaborators'. Other smaller groups, such as EKKA, continued the anti-occupation fight with sabotage and other actions. By 1944, ELAS had the numerical advantage in armed fighters, having more than 50,000 of them and an extra 500,000 working as reserves or logistical support personnel (Efedrikos ELAS). In contrast, EDES and EKKA had around 10,000 fighters each.[18]

After the declaration of the formation of the Security Battalions, KKE and EAM implemented a pre-emptive policy of terror, mainly in the Peloponnese countryside areas close to garrisoned German units, intending to ensure civilian allegiance.[19] As the Communist position strengthened, so did the numbers of the "Security Battalions", with both sides engaged in skirmishes. The most notorious example of these skirmishes is the Battle of Meligalas. The ELAS victory was followed by a massacre, during which prisoners and civilians were executed near a well.[20]

Egypt "mutiny" and the Lebanon Conference

In March 1944, EAM established the Political Committee of National Liberation (Politiki Epitropi Ethnikis Apeleftherosis, or PEEA), in effect a third Greek government to rival those in Athens and Cairo. PEEA was dominated by, but not composed exclusively of Communists.

The movement threatened Allied unity, angering Great Britain and the United States. British and Greek troops loyal to the exiled government moved to suppress the PEEA. Approximately 5,000 Greek soldiers and officers were disarmed and deported to prison camps. After the mutiny, Allied economic aid to the EAM almost stopped.

In May 1944, representatives from all political parties and resistance groups came together at the Lebanon Conference under the leadership of Georgios Papandreou. The conference ended with an agreement (the National Contract) for a government of national unity consisting of 24 ministers (6 to be EAM members).

Confrontation: 1944

By 1944, EDES and ELAS each saw the other to be their great enemy. They both saw that the Germans were going to be defeated and were a temporary threat. For the ELAS, the British represented their major problem, even while the majority of Greeks saw the British as their major hope for an end to the war.[21]

From the Lebanon Conference to the outbreak

By the summer of 1944, it was obvious that the Germans would soon withdraw from Greece, as Soviet forces were advancing into Romania and towards Yugoslavia, threatening to cut off the retreating Germans. The government-in-exile, now led by prominent liberal Georgios Papandreou, moved to Italy, in preparation for its return to Greece. Under the Caserta Agreement of September 1944, all resistance forces in Greece were placed under the command of a British officer, General Ronald Scobie.[22] The Western Allies arrived in Greece in October, by which time the Germans were in full retreat and most of Greece's territory had already been liberated by Greek partisans. On October 13, British troops entered Athens, the only area still occupied by the Germans, and Papandreou and his ministers followed six days later.[23]

There was little to prevent ELAS from taking full control of the country. With the German withdrawal, ELAS units had taken control of the countryside and most cities. The issue of disarming the resistance organizations was a cause of friction between the Papandreou government and its EAM members. Advised by British ambassador Reginald Leeper, Papandreou demanded the disarmament of all armed forces apart from the Sacred Band and the III Mountain Brigade and the constitution of a National Guard under government control. The Communists, believing that it would leave the ELAS defenseless against its opponents, submitted an alternative plan of total and simultaneous disarmament, but Papandreou rejected it, causing EAM ministers to resign from the government on December 2. On December 1, Scobie issued a proclamation calling for the dissolution of ELAS. Command of ELAS was KKE's greatest source of strength, and KKE leader Siantos decided that the demand for ELAS's dissolution must be resisted.

The Dekemvriana events

On 1 December 1944, the Greek "National Unity" government of Papandreou announced an ultimatum for the general disarmament by 10 December of all guerrilla forces, excluding the tactical forces (the III Greek Mountain Brigade and the Sacred Band);[24] and also a part of EDES and ELAS that would be used, if it was necessary, in Allied operations in Crete and Dodecanese against the remaining German Army units. The EAM called for a general strike and announced the reorganization of the Central Committee of ELAS. A demonstration, forbidden by the government, was organised by EAM on 3 December.

The demonstration involved at least 200,000 people[25] marching in Athens on Panepistimiou Street towards the Syntagma Square. British tanks along with police units had been scattered around the area, blocking the way of the demonstrators.[26] The shootings began when the marchers had arrived at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, in front of the Royal palace, above Syntagma Square. More than 28 demonstrators were killed, and 148 were injured. This signaled the beginning of the Dekemvriana (Greek: Δεκεμβριανά, "the December events"), a 37-day period of full-scale fighting in Athens between EAM fighters and smaller parts of ELAS and the forces of the British army and the government.

Conflicts continued throughout December with the forces confronting the EAM slowly gaining the upper hand. By 12 December, ΕΑΜ was in control of most of Athens, Piraeus and the suburbs. The government and British forces were confined only in the centre of Athens, in an area that was ironically called Scobia (Scobie's country) by the guerrillas. The British, alarmed by the initial successes of EAM-ELAS and outnumbered, flew in the 4th Indian Infantry Division from Italy as emergency reinforcements.

By early January, EAM forces had lost the battle. Despite Churchill's intervention, Papandreou resigned and was replaced by Lieutenant General Nikolaos Plastiras. On 15 January 1945, Scobie agreed to a ceasefire in exchange for the ELAS's withdrawal from its positions at Patras and Thessaloniki and its demobilization in the Peloponnese.

Interlude: 1945–1946

In February 1945, the various Greek parties signed the Treaty of Varkiza, with the support of all the Allies. It provided for the complete demobilisation of the ELAS and all other paramilitary groups, amnesty for only political offenses, a referendum on the monarchy and a general election to be held as soon as possible. The KKE remained legal and its leader, Nikolaos Zachariadis, who returned from Dachau at the end of May 1945, formally stated that the KKE's objective was now for a "people's democracy" to be achieved by peaceful means. There were dissenters such as former ELAS leader Aris Velouchiotis. The KKE disavowed Velouchiotis when he called on the veteran guerrillas to start a second struggle; shortly afterwards, he committed suicide surrounded by security forces.[27]

The Treaty of Varkiza transformed the KKE's political defeat into a military one. The ELAS's existence was terminated. The amnesty was not comprehensive because many actions during the German occupation and the Dekemvriana were classified as criminal, exempting the perpetrators from the amnesty. Lawsuits for criminal offences began to be filed. It is estimated that around 80,000 people were prosecuted.[28] As a result, a number of veteran partisans hid their weapons in the mountains, and 5,000 of them escaped to Yugoslavia although that was not encouraged by the KKE's leadership.

In 1945 and 1946, anti-communist forces allegedly killed about 1,190 Communist civilians and tortured many others. Entire villages that had helped the partisans were attacked. Some claimed that anti-communist forces admitted that they were "retaliating" for their suffering under ELAS rule.[29]

The KKE boycotted the March 1946 elections, which were won by the monarchist United Alignment of Nationalists (Inomeni Parataxis Ethnikofronon), the main member of which was Konstantinos Tsaldaris's People's Party. The KKE reversed its former political position after the arrival of Zachariadis. The change of political attitude and the choice to escalate the crisis derived primarily from the conclusion that regime subversion, which had not been successful in December 1944, could now be achieved. A referendum in September 1946 favored the retention of the monarchy, but the KKE claimed that it had been rigged. King George returned to Athens.

The king's return to Greece reinforced British influence in the country. Nigel Clive, then a liaison officer to the Greek government and later the head of the Athens station of MI6, stated, "Greece was a kind of British protectorate, but the British ambassador was not a colonial governor." There were to be six changes of prime ministers within just two years, an indication of the instability that would characterise the country's political life.

Civil War: 1946–1949

Crest: 1946–1948

Fighting resumed in March 1946, as a group of 30 ex-ELAS members attacked a police station in the village of Litochoro, killing the policemen, the night before the elections. The next day, the Rizospastis, the KKE's official newspaper, announced, "Authorities and gangs fabricate alleged communist attacks". Armed bands of ELAS' veterans were then infiltrating Greece through mountainous regions near the Yugoslav and Albanian borders. They were now organized as the Democratic Army of Greece (Dimokratikos Stratos Elladas, DSE). ELAS veteran Markos Vafiadis (known as "General Markos") was sent by the KKE to organize already existing troops, and took command from a base in Yugoslavia.[30]

The Yugoslav and Albanian Communist governments supported the DSE fighters, but the Soviet Union remained ambivalent.[30] The KKE kept an open line of communication with the Soviet Communist Party, and its leader, Nikos Zachariadis, had visited Moscow on more than one occasion. No evidence exists of mercenaries, although the guerrillas received various types of assistance from their Balkan Communist neighbours.[31] One example of an international volunteer joining the ranks of the DSE was Turkish Communist Mihri Belli.[32]

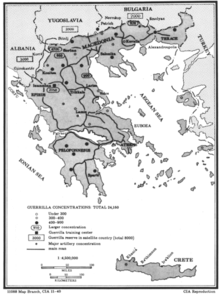

By late 1946, the DSE was able to deploy about 16,000 partisans, including 5,000 in the Peloponnese and other areas of Greece. According to the DSE, its fighters "resisted the reign of terror that right-wing gangs conducted across Greece". In the Peloponnese especially, local party officials, headed by Vangelis Rogakos, had established a plan long before the decision to go to guerrilla war under which the numbers of partisans operating in the mainland would be inversely proportional to the number of soldiers that the enemy would concentrate in the region. According to the study, the DSE III Division in the Peloponnese numbered between 1,000 and 5,000 fighters in early 1948.[33]

Rural peasants were caught in the crossfire. When DSE partisans entered a village asking for supplies, citizens were supportive (in previous years, EAM could count on two million members across the whole country) or did not resist. When government troops arrived at the same village, citizens who had supplied the partisans were immediately denounced as Communist sympathizers and usually imprisoned or exiled. In rural areas, the government also used a strategy, which had been advised by US advisers, of evacuating villages under the pretext that they were under direct threat of Communist attack. That would deprive the partisans of supplies and recruits and simultaneously raise antipathy towards them.[34]

The Greek Army now numbered about 90,000 men and was gradually being put on a more professional footing. The task of re-equipping and training the army had been carried out by its fellow Western Allies. By early 1947, however, Britain, which had spent £85 million in Greece since 1944, could no longer afford this burden. US President Harry S. Truman announced that the United States would step in to support the Greek government against Communist pressure. That began a long and troubled relationship between Greece and the United States. For several decades to come, the US ambassador advised the king on important issues, such as the appointment of the prime minister.[citation needed]

Through 1947, the scale of fighting increased. The DSE launched large-scale attacks on towns across northern Epirus, Thessaly, Peloponnese, and Macedonia, provoking the army into massive counteroffensives, which met no opposition as the DSE melted back into the mountains and its safe havens across the northern borders. In the Peloponnese, where General Georgios Stanotas was appointed area commander, the DSE suffered heavily, with no way to escape to mainland Greece. In general, army morale was low, and it would be some time before US support became apparent.

Conventional warfare

In September 1947, however, the KKE's leadership decided to move from guerrilla tactics to fullscale conventional war despite the opposition of Vafiadis. In December, the KKE announced the formation of a Provisional Democratic Government, with Vafiadis as prime minister; that led the Athens government to ban the KKE. No foreign government recognized this government. The new strategy led the DSE into costly attempts to seize a major town as its seat of government, and in December 1947, 1,200 DSE fighters were killed in the Battle of Konitsa. At the same time, the strategy forced the government to increase the size of the army. With control of the major cities, the government cracked down on KKE members and sympathizers, many of whom were imprisoned on the island of Makronisos.

Despite setbacks, such as the defeat at Konitsa, the DSE reached the height of its power in 1948, extending its operations to Attica, within 20 km of Athens. It drew on more than 20,000 fighters, both men and women, and a network of sympathizers and informants in every village and suburb.

Among analysts emphasising the KKE's perceived control and guidance by foreign powers, such as the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia, some estimate that of the DSE's 20,000 fighters, 14,000 were Slavic Macedonians from Greek Macedonia.[35][better source needed] Expanding their reasoning, they conclude that given their important role in the battle,[36] the KKE changed its policy towards them. At the fifth Plenum of KKE on January 31, 1949, a resolution was passed declaring that after KKE's victory, the Slavic Macedonians would find their national restoration within a united Greek state.[37] The alliance of the DSE with the Slavic Macedonians caused the official Greek state propaganda to call the Communist guerrillas Eamovulgari (from EAM plus Bulgarians). The Communists called their opponents Monarchofasistes (monarchist fascists).

The extent of such involvement remains contentious and unclear; some emphasize that the KKE had in total 400,000 members (or 800,000, according to some sources) immediately prior to December 1944 and that during the Civil War, 100,000 ELAS fighters, mostly KKE members, were imprisoned, and 3,000 were executed. Supporters emphasise instead the DSE's conduct of a war effort across the country aimed at "a free and liberated Greece from all protectors that will have all the nationalities working under one Socialist State".

DSE divisions conducted guerrilla warfare across Greece. III Division, with 20,000 men in 1948, controlled 70% of the Peloponnese politically and militarily; battalions named after ELAS formations were active in northwestern Greece, and in the islands of Lesvos, Limnos, Ikaria, Samos, Crete, and Evoia, and the bulk of the Ionian Islands. Advisers, funds, and equipment were now flooding into the country from Western Allies, and under their guidance the Greek army launched a series of major offensives into the mountains of central Greece. Although the offensives did not achieve all their objectives, they inflicted serious defeats on the DSE.

Communist removal of the children and the Queen's Camps

The removal of children by both sides was another highly emotive and contentious issue.[38] About 30,000 children were forcibly taken by the DSE from territories they controlled to Eastern Bloc countries.[39] The issue drew the attention of international public opinion, and a United Nations Special Committee issued a report, stating that "some children have in fact been forcibly removed."[40]

The Communist leadership claimed that children evacuated from Greece at the request of "popular organizations and parents".[40]

According to other researchers, the Greek government also followed a policy of displacement by adopting children of the guerrillas and placing them in indoctrination camps.[41]

According to the official KKE story, the Provisional Government issued a directive for the evacuation of all minors from 4 to 14 years old for protection from the war and problems linked to it, as was stated clearly according to the decisions of the Provisional Government on March 7, 1948.[42] According to non-KKE accounts, the children were abducted to be indoctrinated as Communist Janissaries.[43] Several United Nations General Assembly resolutions appealed for the repatriation of children to their homes.[44] After 50 years, more information regarding the children gradually emerged. Many returned to Greece between 1975 and 1990, with varied views and attitudes toward the Communist faction.[45][46]

Also, however, a UN committee reported at that time "Queen Frederica has already prepared special 'reform camps' in Greek islands for 12,000 Greek children..."[47] During the war, more than 25,000 children, most with parents in the DSE, were also placed in 30 "child towns" under the immediate control of Queen Frederica, something especially emphasised by the left.[citation needed] After 50 years, some of these children, given up for adoption to American families, were retracing their family background in Greece.[48][49][50][51][52][53][54]

End of the war: 1949

The insurgents were demoralised by the bitter split between Stalin and Tito.[15] In June 1948, the Soviet Union and its satellites broke off relations with Tito. In one of the meetings held in the Kremlin with Yugoslav representatives, during the Soviet-Yugoslav crisis,[55] Stalin stated his unqualified opposition to the "Greek uprising". Stalin explained to the Yugoslav delegation that the situation in Greece had always been different from the one in Yugoslavia because the US and Britain would "never permit [Greece] to break off their lines of communication in the Mediterranean". (Stalin used the word svernut, Russian for "fold up", to express what the Greek Communists should do.)

Yugoslavia had been the Greek Communists' main supporter from the years of the occupation. The KKE thus had to choose between its loyalty to the Soviet Union and its relations with its closest ally. After some internal conflict, the great majority, led by party secretary Nikolaos Zachariadis, chose to follow the Soviet Union. In January 1949, Vafiadis was removed from his political and military positions, to be replaced by Zachariadis.

After a year of increasing acrimony, Tito closed the Yugoslav border to the DSE in July 1949, and disbanded its camps inside Yugoslavia. The DSE was still able to use Albanian border territories, a poor alternative. Within the KKE, the split with Tito also sparked a witch hunt for "Titoites" that demoralised and disorganised the ranks of the DSE and sapped support for the KKE in urban areas.

In summer 1948, DSE Division III in the Peloponnese suffered a huge defeat. Lacking ammunition support from DSE headquarters and having failed to capture government ammunition depots at Zacharo in the western Peloponnese, its 20,000 fighters were doomed. The majority (including the commander of the Division, Vangelis Rogakos) were killed in battle with nearly 80,000 National Army troops. The National Army's strategic plan, codenamed "Peristera" (the Greek word for "dove (bird)"), was successful. A number of other civilians were sent to prison camps for helping Communists. The Peloponnese was now governed by paramilitary groups fighting alongside the National Army. To terrify urban areas assisting DSE's III Division, the forces decapitated a number of dead fighters and placed them in central squares.[33] Following defeat in southern Greece, the DSE continued to operate in northern Greece and some islands, but it was a greatly weakened force facing significant obstacles both politically and militarily.

At the same time, the National Army found a talented commander in General Alexander Papagos, commander of the Greek Army during the Greco-Italian War. In August 1949, Papagos launched a major counteroffensive against DSE forces in northern Greece, codenamed Operation Pyrsos ("Torch"). The campaign was a victory for the National Army and resulted in heavy losses for the DSE. The DSE army was now no longer able to sustain resistance in pitched battles. By September 1949, the main body of DSE divisions defending Grammos and Vitsi, the two key positions in northern Greece for the DSE, had retreated to Albania. Two main groups remained within the borders, trying to reconnect with scattered DSE fighters largely in Central Greece.

These groups, numbering 1,000 fighters, left Greece by the end of September 1949. The main body of the DSE, accompanied by its HQ, after discussion with the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and other Communist governments, was moved to Tashkent in the Soviet Union. They were to remain there, in military encampments, for three years. Other older combatants, alongside injured fighters, women and children, were relocated to European socialist states. On October 16, Zachariadis announced a "temporary ceasefire to prevent the complete annihilation of Greece"; the ceasefire marked the end of the Greek Civil War.

Almost 100,000 ELAS fighters and communist sympathizers serving in DSE ranks were imprisoned, exiled, or executed. That deprived the DSE of the principal force still able to support its fight. According to some historians,[56] the KKE's major supporter and supplier had always been Tito, and it was the rift between Tito and the KKE that marked the real demise of the party's efforts to assert power.

Western anti-communist governments allied to Greece saw the end of the Greek Civil War as a victory in the Cold War against the Soviet Union. Communists countered that the Soviets never actively supported the Greek Communist efforts to seize power in Greece. Both sides had, at differing junctures, nevertheless looked to an external superpower for support.

Postwar division and reconciliation

The Civil War left Greece in ruins and in even greater economic distress than it had been following the end of German occupation.[citation needed] Furthermore, it divided the Greek people for ensuing decades, with both sides vilifying their opponents. Thousands languished in prison for many years or were sent into internal exile on the islands of Gyaros and Makronisos.[citation needed] Many others sought refuge in Communist countries or emigrated to Australia, Germany, the US, the UK, Canada, and elsewhere.[citation needed] At least 80,000 people died in the civil war.[6]

The polarization and instability of Greek politics in the mid-1960s was a direct result of the Civil War and the deep divide between the leftist and rightist sections of Greek society. A major crisis as a result was the murder of the left-wing politician Gregoris Lambrakis in 1963, the inspiration for the Costa Gavras political thriller Z. The crisis of the Apostasia followed in 1965, together with the "ASPIDA affair", which involved an alleged coup plot by a left-wing group of officers; the group's alleged leader was Andreas Papandreou, son of Georgios Papandreou, the leader of the Center Union political party and the country's prime minister at the time.

On April 21, 1967, a group of rightist and anti-communist army officers executed a coup d'état and seized power from the government, using the political instability and tension of the time as a pretext. The leader of the coup, Georgios Papadopoulos, was a member of the right-wing military organization IDEA ("Sacred Bond of Greek Officers"), and the subsequent military regime (later referred to as the Regime of the Colonels) lasted until 1974.

After the collapse of the military junta, a conservative government under Konstantinos Karamanlis led to the abolition of monarchy, the legalization of the KKE, and a new constitution, which guaranteed political freedoms, individual rights, and free elections. This period following the fall of the coup and transition to a parliamentary democracy is known as the "metapolitefsi". In 1981, in a major turning point in modern Greek history, the centre-left government of the Panhellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK) allowed a number of DSE veterans who had taken refuge in communist countries to return to Greece and reestablish their former estates, which greatly helped to diminish the consequences of the Civil War in Greek society. The PASOK administration also offered state pensions to former partisans of the anti-Nazi resistance; Markos Vafiadis was honorarily elected as member of the Greek parliament under PASOK's flag.

In 1989, the coalition government between Nea Dimokratia and the Coalition of Left and Progress (Synaspismos), in which the KKE was for a period the major force, suggested a law that was passed unanimously by the Greek Parliament, formally recognizing the 1946–1949 war as a civil war and not merely as a Communist insurgency (Συμμοριτοπόλεμος Symmoritopolemos) (Ν. 1863/89 (ΦΕΚ 204Α΄)).[57][58][59] Under the terms of this law, the war of 1946–1949 was recognized as a Greek Civil War between the National Army and the Democratic Army of Greece, for the first time in Greek postwar history. Under the aforementioned law, the term "Communist bandits" (Κομμουνιστοσυμμορίτες Kommounistosymmorites, ΚΣ), wherever it had occurred in Greek law, was replaced by the term "Fighters of the DSE".[60]

In a 2008 Gallup poll, Greeks were asked "whether it was better that the right wing won the Civil War". 43% responded that it was better for Greece that the right wing won, 13% responded that it would have been better if the left had won, 20% responded "neither" and 24% did not respond.[61]

List of abbreviations

| Abbrev. | Expansion | Translation |

|---|---|---|

| DSE | Δημοκρατικός Στρατός Ελλάδας | Democratic Army of Greece |

| EAM | Εθνικό Απελευθερωτικό Μέτωπο | National Liberation Front |

| EDES | Εθνικός Δημοκρατικός Ελληνικός Σύνδεσμος | National Republican Greek League |

| EKKA | Εθνική και Κοινωνική Απελευθέρωσις | National and Social Liberation |

| ELAN | Ελληνικό Λαϊκό Απελευθερωτικό Ναυτικό | Greek People's Liberation Navy |

| ELAS | Ελληνικός Λαϊκός Απελευθερωτικός Στρατός | Greek People's Liberation Army |

| HQ | Headquarters | |

| KKE | Κομμουνιστικό Κόμμα Ελλάδας | Communist Party of Greece |

| NATO | North Atlantic Treaty Organization | |

| Nazi | National-Socialist; National Socialist German Workers' Party | |

| NOF | Народно Ослободителен Фронт | National Liberation Front (Macedonia) |

| OPLA | Οργάνωση Προστασίας Λαϊκών Αγωνιστών | Organization for the Protection of the People's Struggle |

| PASOK | Πανελλήνιο Σοσιαλιστικό Κίνημα | Panhellenic Socialist Movement |

| PEEA | Πολιτική Επιτροπή Εθνικής Απελευθέρωσης | Political Committee of National Liberation |

| UN | United Nations | |

| USSR | Union of Soviet Socialist Republics | |

| YVE | Υπερασπισταί Βορείου Ελλάδος | Defenders of Northern Greece |

See also

Footnotes

- ^ The Struggle for Greece 1941–1949, C. M.Woodhouse, Hurst & Company, London 2002 (first published 1976), p. 237

- ^ Νίκος Μαραντζίδης, Δημοκρατικός Στρατός Ελλάδας, 1946–1949, Εκδόσεις Αλεξάνδρεια, β'έκδοση, Αθήνα 2010, p. 52

- ^ Νίκος Μαραντζίδης, Δημοκρατικός Στρατός Ελλάδας, (Kayluff a hoe)1946–1949, Εκδόσεις Αλεξάνδρεια, β'έκδοση, Αθήνα 2010, pp. 52, 57, 61–62

- ^ Γενικόν Επιτελείον Στρατού, Διεύθυνσις Ηθικής Αγωγής, Η Μάχη του Έθνους, Ελεύθερη Σκέψις, Athens, 1985, pp. 35–36

- ^ Γενικόν Επιτελείον Στρατού, p. 36

- ^ a b Keridis 2022, p. 54.

- ^ Howard Jones, A New Kind of War (1989)[page needed]

- ^ Edgar O'Ballance, The Greek Civil War: 1944–1949 (1966)[page needed]

- ^ T. Lomperis, From People's War to People's Rule (1996)[page needed]

- ^ "B&J": Jacob Bercovitch and Richard Jackson, International Conflict: A Chronological Encyclopedia of Conflicts and Their Management 1945–1995 (1997)[page needed]

- ^ Γιώργος Μαργαρίτης, Η ιστορία του Ελληνικού εμφυλίου πολέμου ISBN 960-8087-12-0[page needed]

- ^ Nikos Marantzidis and Giorgos Antoniou. "The Axis Occupation and Civil War: Changing trends in Greek historiography, 1941–2002." Journal of Peace Research (2004) 41#2 pp: 223–231.

- ^ Chomsky, Noam (1994). World Orders, Old And New. Pluto Press London.

- ^ Iatrides, John O. (2005). "George F. Kennan and the Birth of Containment: The Greek Test Case". World Policy Journal. 22 (3): 126–145. doi:10.1215/07402775-2005-4005. ISSN 0740-2775.

- ^ a b

Robert Service summarizes Soviet vacillations:

Service, Robert (2007). "22. Western Europe". Comrades!: A History of World Communism. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 266–268. ISBN 9780674025301. Retrieved 2016-10-28.

After the German forces withdrew in October 1944, the Greek Communist Party found its armed force – ELAS – subordinated to the British army with Moscow's consent. But the Greek Communist Party soon opted for insurgency. Clashes occurred between the communists and the British, together with the forces of the new British-backed Greek government. Stalin at the time, however, needed to maintain good relations with the United Kingdom for strategic reasons [...] Without outside help, [...] the revolt petered out. Then Stalin changed his mind, hoping to play off the Americans and British over Greece. [...] By 1946 [the Greek Communists] were eager to resume armed struggle. [...] Zachariadis [...] needed support from Communist states for military equipment, and he gained the desired consent on his trips to Belgrade, Prague and Moscow. [...] But Stalin changed his mind yet again and advised emphasis on political measures rather than the armed struggle. [...] Tito and the Yugoslavs, however, continued to render material assistance and advice to the Greek communists. [...] Stalin reverted to a militant stance after the announcement [1947] of the Marshall Plan and ceased trying to restrain the Greek Communist Party. Soviet military equipment was covertly rushed to Greece. A provisional revolutionary government was proclaimed [24 December 1947]. But it became clear that the Greek Communists as well as their Yugoslav sympathisers had exaggerated their strength and potential. Stalin felt he had been misled, and called for an end to the uprising in Greece. [...] The Yugoslav Communists objected to Stalin's change of policy. [...] Bulgarian Communist leader Traicho Kostov urged that Soviet aid be sent to the Greek insurrectionists. [...] This had disastrous consequences for the Soviet-Yugoslav relationship; it also brought doom to Kostov, who was executed [16 December 1949] with Stalin's connivance at the end of 1948. Stalin himself continued to waffle on the Greek question in the following months [...] but in the end he ordered the communists under Nikos Zachariadis and Markos Vafiadis to end the civil war. [...] Yet, despite being deprived of supplies from Moscow, they refused to stop fighting royalist forces. [...] Ultimately the Communist insurgency stood no chance of succeeding. By the end of 1949 the Communist revolt had been crushed and the remnant of the anti-government forces fled to Albania.

- ^ Andrew Rossos, "Incompatible Allies: Greek Communism and Macedonian Nationalism in the Civil War in Greece, 1943–1949." The Journal of Modern History, Vol. 69, No. 1 (Mar 1997) p.42

- ^ History of National Resistance 1941–1944, v. 1

- ^ Edgar O'Ballance (1966) The Greek Civil War 1944–1949 pp. 65, 105

- ^ Kalyvas 2000, pp. 155–156, 164.

- ^ Moutoulas, Pantelis (2004). Πελοπόννησος 1940–1945: Η περιπέτεια της επιβίωσης, του διχασμού και της απελευθέρωσης [The Peloponnese 1940–1945: The struggle of survival, division, and liberation] (in Greek). Athens: Vivliorama. p. 580.

- ^ Lars Baerentzen, "Occupied Greece," Modern Greek Studies Yearbook (Jan 1998) pp. 281–286

- ^ Gounelas & Parkin-Gounelas 2023, p. 161.

- ^ Sossa Berni Plakidas (2010). Anatoli. Xulon Press. p. 19. ISBN 9781609571337.

- ^ Ζέτα Τζαβάρα, "Ο Δεκέμβρης του 1944 μέσα από την αρθρογραφία των εφημερίδων της εποχής"; Mαργαριτης Γιώργος; Λυμπεράτος Μιχάλης (2010). Δεκέμβρης '44 Οι μάχες στις γειτονιές της Αθήνας (in Greek). Ελευθεροτυπία. p. 77. ISBN 978-9609487399. Archived from the original on 2016-05-27. Retrieved 2012-06-14.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Newspaper "ΠΡΙΝ", 7.12.1997, http://nar4.wordpress.com/2008/12/03/δεκέμβρης-44-αυτά-τα-κόκκινα-σημάδια-εί/

- ^ Κουβαράς, Κώστας (1976). O.S.S. Mε Την Κεντρική Του Ε.Α.Μ. Αμερικάνικη Μυστική Αποστολή Περικλής Στην Κατεχόμενη Ελλάδα (in Greek). Εξάντας. Retrieved June 14, 2011.

- ^ (Grigoriadis 2011, pp. 68–69)

- ^ (Grigoriadis 2011, p. 48)

- ^ Lazou, Vassiliki (2016-12-11). "Η "συμμοριοποίηση" του κράτους" [The gangification of the state]. Η Εφημεριδα των Συντακτων (in Greek). Athens. Archived from the original on 2016-12-11. Retrieved 2016-12-11.

- ^ a b Charles R. Shrader (1999). The Withered Vine: Logistics and the Communist Insurgency in Greece, 1945-1949. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 171–188. ISBN 978-0-275-96544-0.

- ^ Nachmani, Amikam (1990). "Civil War and Foreign Intervention in Greece: 1946-49". Journal of Contemporary History. 25 (4): 497. doi:10.1177/002200949002500406. ISSN 0022-0094. JSTOR 260759. S2CID 159813355.

- ^ Maria Katsounaki (4 August 2009). "The Turk in the Greek ranks". I Kathimerini.

- ^ a b The Civil War in Peloponnese, A. Kamarinos

- ^ Nam, The True Story of Vietnam, 1986

- ^ Ζαούσης Αλέξανδρος. Η Τραγική αναμέτρηση, 1945–1949 – Ο μύθος και η αλήθεια (ISBN 960-7213-43-2).

- ^ Speech presented by Nikos Zachariadis at the Second Congress of the National Liberation Front (NOF) of the ethnic Macedonians from Greek Macedonia, published in Σαράντα Χρόνια του ΚΚΕ 1918–1958, Athens, 1958, p. 575.

- ^ KKE Official documents, vol 8

- ^ The Paidomazoma: Tough Times for the Children of Greece, New Histories October 30, 2011

- ^ C. M. Woodhouse, Modern Greece, Faber and Faber, 1991, 1992, pp. 259.

- ^ a b Lars Barentzen, The 'Paidomazoma' and the Queen's Camps, p 129

- ^ Myrsiades, Cultural Representation in Historical Resistance, p. 333

- ^ KKE, official Documents v. 6 1946–1949, pp. 474–476

- ^ Richard Clogg, A Concise History of Greece, Cambridge University Press, 1992, p. 141.

- ^ Ods Home Page[permanent dead link]

- ^ Dimitris Servou, The Paidomazoma and who is afraid of Truth, 2001

- ^ Thanasi Mitsopoulou "We brought up as Greeks", Θανάση Μητσόπουλου "Μείναμε Έλληνες"

- ^ Kenneth Spencer, "Greek Children", The New Statesman and Nation 39 (January 14, 1950): 31–32.

- ^ "Βήμα" 20.9.1947

- ^ "Νέα Αλήθεια" Λάρισας 5.12.1948

- ^ "Δημοκρατικός Τύπος" 20.8.1950

- ^ Δ. Κηπουργού: "Μια ζωντανή Μαρτυρία".- D. Kipourgou " A live testimony"

- ^ The'Paidomazoma' and the Queen's Camps, in Lars Baerentzen et al.- Λαρς Μπαέρεντζεν: "Το παιδομάζωμα και οι παιδουπόλεις"

- ^ Δημ. Σέρβου: "Που λες... στον Πειραιά" – Dimitri Servou "Once upon a time...in Piraeus"

- ^ Politiko-Kafeneio.gr. "Politiko-Kafeneio.gr". Politikokafeneio.com. Retrieved 2014-02-28.

- ^ Djilas, Milovan (1962, 1990) Conversations with Stalin, pp. 181–182

- ^ Gounelas & Parkin-Gounelas 2023, pp. 117-8 & 146-7.

- ^ tovima.dolnet.gr Dead URL (archive date = December 30, 2007) (access date = July 31, 2008)

- ^ enet.gr/online/online_fpage_text Archived 2008-12-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-07-22. Retrieved 2014-01-07.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Article 1 of the Law 1863/1989

- ^ "60 χρόνια μετά, ο Εμφύλιος διχάζει | Ελλάδα | Η ΚΑΘΗΜΕΡΙΝΗ". News.kathimerini.gr. 2013-10-29. Archived from the original on 2013-06-07. Retrieved 2014-02-28.

Bibliography

Scholarly studies

- Bærentzen, Lars, John O. Iatrides, Ole Langwitz Smith, eds. Studies in the history of the Greek Civil War, 1945–1949, 1987

- Byford-Jones, W. The Greek Trilogy: Resistance–Liberation–Revolution, London, 1945

- Carabott, Philip and Thanasis D. Sfikas, The Greek Civil War, (2nd ed 2017)

- Christodoulakis, Nicos. "Country failure and social grievances in the Greek Civil War 1946–1949: An economic approach." Defence and Peace Economics 26.4 (2015): 383–407.

- Close, David H. The Greek Civil War (Routledge, 2014).

- Close, David H. (ed.), The Greek civil war 1943–1950: Studies of Polarization, Routledge, 1993 (ISBN 041502112X)

- Gerolymatos, André. Red Acropolis, Black Terror: The Greek Civil War and the Origins of Soviet-American Rivalry, 1943–1949 (2004).

- Goulter, Christina J. M. "The Greek Civil War: A National Army's Counter-insurgency Triumph," Journal of Military History (July 2014) 78:3 pp: 1017–1055.

- Hondros, John. Occupation and resistance: the Greek agony, 1941–44 (Pella Publishing Company, 1983)

- Iatrides, John O. "Revolution or self-defense? Communist goals, strategy, and tactics in the Greek civil war." Journal of Cold War Studies (2005) 7#3 pp: 3–33.

- Iatrides, John O., and Nicholas X. Rizopoulos. "The international dimension of the Greek Civil War." World Policy Journal 17.1 (2000): 87–103. online

- Iatrides, John O. "George F. Kennan and the birth of containment: the Greek test case." World Policy Journal 22.3 (2005): 126–145. online

- Jones, Howard. 'A New Kind of War' America's Global Strategy and the Truman Doctrine in Greece (1989)

- Kalyvas, S. N. The Logic of Violence in Civil War, Cambridge, 2006

- Karpozilos, Kostis. "The defeated of the Greek Civil War: From fighters to political refugees in the Cold War." Journal of Cold War Studies 16.3 (2014): 62–87. [1]

- Koumas, Manolis. "Cold War Dilemmas, Superpower Influence, and Regional Interests: Greece and the Palestinian Question, 1947–1949." Journal of Cold War Studies 19.1 (2017): 99–124.

- Kousoulas, D. G. Revolution and Defeat: The Story of the Greek Communist Party, London, 1965

- Marantzidis, Nikos. "The Greek Civil War (1944–1949) and the International Communist System." Journal of Cold War Studies 15.4 (2013): 25–54.

- Mazower. M. (ed.) After the War was Over. Reconstructing the Family, Nation and State in Greece, 1943–1960 Princeton University Press, 2000 (ISBN 0691058423)[2]

- Nachmani, Amikam. "Civil War and Foreign Intervention in Greece: 1946–49" Journal of Contemporary History (1990) 25#4 pp. 489–522 online

- Nachmani, Amikam. International intervention in the Greek Civil War, 1990 (ISBN 0275933679)

- Plakoudas, Spyridon. The Greek Civil War: Strategy, Counterinsurgency and the Monarchy (2017)

- Sarafis, Marion (editor), Greece – from resistance to civil war, (Bertrand Russell House Leicester 1980) (ISBN 0851242901)

- Sarafis, Marion, & Martin Eve (editors), Background to contemporary Greece, (vols 1 & 2, Merlin Press London 1990) (ISBN 0850363934, 0850363942)

- Sarafis, Stefanos. ELAS: Greek Resistance Army, Merlin Press London 1980 (Greek original 1946 & 1964)

- Sfikas, Thanasis D. The Greek Civil War: Essays on a Conflict of Exceptionalism and Silences (Routledge, 2017).

- Stavrakis, Peter J. Moscow and Greek Communism, 1944–1949 (Cornell University Press, 1989) excerpt.

- Tsoutsoumpis, Spyros. "The Will to Fight: Combat, Morale, and the Experience of National Army Soldiers during the Greek Civil War, 1946–1949." International Journal of Military History and Historiography 1.aop (2022): 1–33.

- Vlavianos. Haris. Greece, 1941–49: From Resistance to Civil War: The Strategy of the Greek Communist Party (1992)

British role

- Alexander, G. M. The Prelude to the Truman Doctrine: British Policy in Greece 1944–1947 (1982)

- Chandler, Geoffrey. The divided land: an Anglo-Greek tragedy, (Michael Russell Norwich, 1994) (ISBN 0859552152)

- Churchill, Winston S. The Second World War

- Clive, Nigel. A Greek Experience: 1943–1948 (Michael Russell, 1985.)

- Frazier, Robert. Anglo-American relations with Greece: the coming of the Cold War 1942–47 (1991)

- Goulter-Zervoudakis, Christina. "The politicization of intelligence: The British experience in Greece, 1941–1944." Intelligence and National Security (1998) 13#1 pp: 165–194.

- Iatrides, John O., and Nicholas X. Rizopoulos. "The International Dimension of the Greek Civil War." World Policy Journal (2000): 87–103. in JSTOR

- Myers, E. C. F. Greek entanglement (Sutton Publishing, Limited, 1985)

- Richter, Heinz. British Intervention in Greece. From Varkiza to Civil War, London, 1985 (ISBN 0850363012)

- Sfikas, Athanasios D. British Labour Government and The Greek Civil War: 1945–1949 (Edinburgh University Press, 2019).

Historiography

- Lalaki, Despina. "On the Social Construction of Hellenism Cold War Narratives of Modernity, Development and Democracy for Greece." Journal of Historical Sociology (2012) 25#4 pp: 552–577. online

- Marantzidis, Nikos, and Giorgos Antoniou. "The axis occupation and civil war: Changing trends in Greek historiography, 1941–2002." Journal of Peace Research (2004) 41#2 pp: 223–231. online

- Nachmani, Amikam. "Civil War and Foreign Intervention in Greece: 1946–49." Journal of Contemporary History (1990): 489–522. in JSTOR

- Plakoudas, Spyridon. The Greek Civil War: Strategy, Counterinsurgency and the Monarchy (2017) pp 119–127.

- Stergiou, Andreas. "Greece during the cold war." Southeast European and Black Sea Studies (2008) 8#1 pp: 67–73.

- Van Boeschoten, Riki. "The trauma of war rape: A comparative view on the Bosnian conflict and the Greek civil war." History and Anthropology (2003) 14#1 pp: 41–44.

Primary sources

- Andrews, Kevin. The flight of Ikaros, a journey into Greece, Weidenfeld & Nicolson London 1959 & 1969

- Capell, R. Simiomata: A Greek Note Book 1944–45, London, 1946

- Clive, Nigel. A Greek experience 1943–1948, ed. Michael Russell, Wilton Wilts.: Russell, 1985 (ISBN 0859551199)

- Clogg, Richard. Greece, 1940–1949: Occupation, Resistance, Civil War: a Documentary History, New York, 2003 (ISBN 0333523695)

- Danforth Loring, Boeschoten Riki Van Children of the Greek Civil War: refugees and the politics of memory, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2012

- Gounelas, C. Dimitris; Parkin-Gounelas, Ruth (2023). John Mulgan and the Greek Left. Wellington, New Zealand: Te Herenga Waka University Press. ISBN 978-17769206-79. [Te Herenga Waka University Press| https://teherengawakapress.co.nz/] see [3]

- Hammond, N. G. L. Venture into Greece: With the Guerrillas, 1943–44, London, 1983 (Like Woodhouse, he was a member of the British Military Mission)

- Keridis, Dimitris (2022). Historical Dictionary of Modern Greece. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9781442264717. OCLC 1335862047.

- Matthews, Kenneth. Memories of a mountain war – Greece 1944–1949, Longmans London 1972 (ISBN 0582103800)

- Petropoulos, Elias. Corpses, corpses, corpses (ISBN 9602110813)

- C. M. Woodhouse, Apple of Discord: A Survey of Recent Greek Politics in their International Setting, London, 1948 (Woodhouse was a member of the British Military Mission to Greece during the war)

- Woodhouse, C. M. The Struggle for Greece, 1941–1949, Oxford University Press, 2018 (ISBN 1787382567)

Greek sources

The following are available only in Greek:

- Ευάγγελος Αβέρωφ, Φωτιά και τσεκούρι. Written by ex-New Democracy leader Evangelos Averoff – initially in French. (ISBN 9600502080)

- Γενικόν Επιτελείον Στρατού, Διεύθυνσις Ηθικής Αγωγής, Η Μάχη του Έθνους, Ελεύθερη Σκέψις, Athens, 1985. Reprinted edition of the original, published in 1952 by the Hellenic Army General Staff.

- Γιώργος Δ. Γκαγκούλιας, H αθέατη πλευρά του εμφυλίου. Written by an ex-ELAS fighter. (ISBN 9604261878)

- "Γράμμος Στα βήματα του Δημοκρατικού Στρατού Ελλάδας Ιστορικός – Ταξιδιωτικός οδηγός", "Σύγχρονη Εποχή" 2009 (ISBN 978-9604510801)

- Γρηγοριάδης, Σόλων Νεόκοσμος (2011). Ν. Ζαχαριάδης: Ο μοιραίος ηγέτης. Ιστορία της σύγχρονης Ελλάδας 1941–1974. Vol. 4. Athens: Κυριακάτικη Ελευθεροτυπία.

- "Δοκίμιο Ιστορίας του ΚΚΕ", τόμος Ι. History of the Communist Party of Greece, issued by its Central Committee in 1999.

- Φίλιππος Ηλιού, Ο Ελληνικός Εμφύλιος Πόλεμος – η εμπλοκή του ΚΚΕ, (The Greek civil war – the involvement of the KKE, Themelion Athens 2004 ISBN 9603103055)

- Δημήτριος Γ. Καλδής, Αναμνήσεις από τον Β' Παγκοσμιο Πολεμο, (Memories of the Second World War, private publication Athina 2007)

- Αλέξανδος Ζαούσης, Οι δύο όχθες, Athens, 1992

- Αλέξανδος Ζαούσης, Η τραγική αναμέτρηση Athens, 1992

- Α. Καμαρινού, "Ο Εμφύλιος Πόλεμος στην Πελοπόνησσο", Brigadier General of DSE's III Division, 2002

- "ΚΚΕ, Επίσημα Κείμενα", τόμοι 6,7,8,9. The full collection of KKE's official documents of this era.

- Μιχάλης Λυμπεράτος, Στα πρόθυρα του Εμφυλίου πολέμου: Από τα Δεκεμβριανά στις εκλογές του 1946–1949, "Βιβλιόραμα", Athens, 2006

- Νίκος Μαραντζίδης, Γιασασίν Μιλλέτ (ISBN 9605241315)

- Margaritis, Giorgos (2001). Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Εμφυλίου Πολέμου 1946–1949 [History of the Greek Civil War 1946–1949, Volume 2] (Second ed.). Athens: Vivliorama. ISBN 960-8087-10-4. (2 vols.)

- Σπύρος Μαρκεζίνης, Σύγχρονη πολιτική ιστορία της Ελλάδος, Athens, 1994

- Γεώργιος Μόδης, Αναμνήσεις, Thessaloniki, 2004 (ISBN 9608396050)

- Γιώργου Μπαρτζώκα, "Δημοκρατικός Στρατός Ελλάδας", Secretary of the Communist organization of Athens of KKE in 1945, 1986.

- Μαντώ Νταλιάνη – Καραμπατζάκη, Παιδιά στη δίνη του ελληνικού εμφυλίου πολέμου 1946–1949, σημερινοί ενήλικες, Μουσείο Μπενάκη, 2009, ISBN 978-9609317108

- Περιοδικό "Δημοκρατικός Στράτος", Magazine first issued in 1948 and re-published as an album collection in 2007.

- Αθανάσιος Ρουσόπουλος, Διακήρυξης του επί κατοχής πρόεδρου της Εθνικής Αλληλεγγύης (Declaration during the Occupation by the chairman of National Solidarity Athanasios Roussopoulos, Athens, published Athens 11 July 1947)

- Στέφανου Σαράφη, "Ο ΕΛΑΣ",written by the military leader of ELAS, General Sarafi in 1954.

- Δημ. Σέρβου, "Που λες... στον Πειραιά", written by one of DSE fighters.

Other languages

- Anon, Egina: Livre de sang, un requisitoire accablant des combattants de la résistance condamnés à mort, with translations by Paul Eluard, Editions "Grèce Libre" c. 1949

- Comité d'Aide à la Grèce Démocratique, Macronissos: le martyre du peuple grec, (translations by Calliope G. Caldis) Geneva 1950

- Dominique Eude, Les Kapetanios (in French, Greek and English), Artheme Fayard, 1970

- Hagen Fleischer, Im Kreuzschatten der Maechte Griechenland 1941–1944 Okkupation – Resistance – Kollaboration (2 vols., New York: Peter Lang, 1986), 819 pp

External links

- A full referenced history of DSE

- Greek Civil War Archive at marxists.org

- Andartikos – a short history of the Greek Resistance, 1941–5 on libcom.org/history

- Dangerous Citizens Online online version of Neni Panourgiá's Dangerous Citizens: The Greek Left and the Terror of the State ISBN 978-0823229680

- Απολογισμός των 'Δεκεμβριανών' (only in Greek) Εφημερίδα ΤΟ ΒΗΜΑ-Δεκέμβρης 1944:60 χρόνια μετά

- Battle of Grammos-Vitsi The decisive battle which ended the Greek Civil War