HMS Onslow (G17)

Onslow in 1943 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Onslow |

| Ordered | 3 September 1939 |

| Builder | John Brown & Company, Clydebank |

| Laid down | 1 July 1940 |

| Launched | 31 March 1941 |

| Commissioned | 8 October 1941 |

| Decommissioned | April 1947 |

| Fate | Transferred to Pakistan, 1949 |

| Name | PNS Tippu Sultan |

| Namesake | Tippu Sultan |

| Commissioned | 1949 |

| Decommissioned | 1979 |

| Out of service | 1957 |

| Reinstated | 1960 |

| Fate | Scrapped, 1980 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | O-class destroyer |

| Displacement | 1,610 long tons (1,636 t) (standard) |

| Length | 345 ft (105.2 m) (o/a) |

| Beam | 35 ft (10.7 m) |

| Draught | 13 ft 6 in (4.1 m) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion | 2 × shafts; 2 × geared steam turbines |

| Speed | 37 knots (69 km/h; 43 mph) |

| Range | 3,850 nmi (7,130 km; 4,430 mi) at 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph) |

| Complement | 176+ |

| Armament |

|

HMS Onslow was an O-class destroyer of the Royal Navy. The O-class were intermediate destroyers, designed before the outbreak of the Second World War to meet likely demands for large number of destroyers. They had a main gun armament of four 4.7 in (120 mm) guns, and had a design speed of 36 kn (41 mph; 67 km/h). Onslow was ordered on 2 October 1939 and was built by John Brown & Company at their Clydebank, Glasgow shipyard, launching on 31 March 1941 and completing on 8 October 1941.

Onslow served with the Home Fleet during the war, with a major activity being escorting Arctic Convoys to the Soviet Union. She sank the German submarine U-589 in September 1942 and in December that year took part in the Battle of the Barents Sea in 1942, while escorting Convoy JW 51B to Russia. The convoy escorts held off attacks from the powerful Admiral Hipper, with Onslow being heavily damaged and her captain, Robert Sherbrooke, severely injured. She also saw detached service in the Mediterranean, covering the Malta Convoy Operation Harpoon in June 1942, and protected invasion shipping in the English Channel from German attack before and after the Normandy landings in mid-1944.

The ship was sold to the Pakistan Navy in 1948, and was renamed Tippu Sultan. Tippu Sultan was converted to a Type 16 anti-submarine frigate from 1957 to 1959, and took part in the 1965 and 1971 wars with India, remaining in service until 1980.

Design

The O-class (and the following P-class) were designed prior to the outbreak of the Second World War to meet the Royal navy's need for large numbers of destroyers in the event of war occurring. They were an intermediate between the large destroyers designed for fleet operations (such as the Tribal-class) and the smaller and slower Hunt-class escort destroyers.[1][2]

Onslow was 345 ft (105.16 m) long overall, 337 ft (102.72 m) at the waterline and 328 ft 9 in (100.20 m) between perpendiculars, with a beam of 35 ft (10.67 m) and a draught of 9 ft (2.74 m) mean and 13 ft 6 in (4.11 m) full load. Displacement was 1,610 long tons (1,636 t) standard and 2,200 long tons (2,235 t) full load.[1][3] Two Admiralty three-drum boilers fed steam at 300 psi (2,100 kPa) and 620 °F (327 °C) to two sets of Parsons single-reduction geared steam turbines which drove two propeller shafts. The machinery was rated at 40,000 shp (30,000 kW) giving a maximum speed of 36.75 kn (42.3 mph; 68.1 km/h), corresponding to 33 kn (38 mph; 61 km/h) at deep load 500 long tons (508 t) of oil was carried, giving a radius of 3,850 nmi (4,430 mi; 7,130 km) at 20 kn (23 mph; 37 km/h).[3] Onslow was configured as a leader for a destroyer flotilla, and as such had a crew of 217 officers and men.[1]

Onslow had a main gun armament of four 45-calibre 4.7-inch (120 mm) Mark IX guns in single mounts. The ship was designed to carry two quadruple 21-inch (533 mm) torpedo tubes, but early experience of the vulnerability of destroyers to air attack off Norway and during the evacuation from Dunkirk in 1940 resulted in the armament of the O-class being revised during construction, with the aft set of torpedo-tubes removed and replaced by a single 4 in (102 mm) QF Mark V anti-aircraft gun,[4][5] although the 4-inch gun was later removed and the second bank of torpedo tubes re-instated.[6] Onslow was completed with a close-in anti-aircraft armament of one quadruple 2-pounder "pom-pom" mount together with four single Oerlikon 20 mm cannon, with two on the bridge wings and two further aft abreast the searchlight platform.[3][7] After April 1943, the single Oerlikon mounts abreast the searchlights were replaced by twin mounts.[6] Four depth charge throwers were fitted, with 60 depth charges carried.[3][a]

Onslow was refitted and rearmed in 1948 as part of her sale to Pakistan. More modern fire control equipment was fitted and the Oerlikon guns were replaced by single Bofors 40 mm anti-aircraft guns, with a twin Bofors 40 mm mount replacing the quadruple pom-pom.[9] Between 1957 and 1959, the ship was refitted as a Type 16 frigate, which resulted in a completely revised armament being fitted. A twin 4 inch gun was mounted forward with a close-in anti-aircraft armament of five Bofors 40 mm guns (one twin and three singles). Anti-submarine armament consisted of two Squid anti-submarine mortars, while a quadruple set of 21-inch torpedo tubes were fitted.[10][11]

Service history

The ship was ordered as part of the Second Emergency Flotilla as Packenham on 2 October 1939,[12] at a contract price of £416,770 (excluding government provided equipment such as armament),[13] and was laid down at John Brown & Company's Clydebank shipyard on 1 July 1940.[14][15] In early 1941, the ship swapped names with the destroyer Onslow, also under construction, and was launched as Onslow on 31 March 1941.[14][15][b] Onslow was damaged by a bomb during an air raid on 3 June 1941,[17] delaying completion by about a month.[6] Onslow commissioned on 23 September 1941,[17] with construction completing on 8 October 1941.[14][15]

1941

Attached to the Home Fleet, Onslow served mostly as an escort to Arctic convoys.[18] After work-up, Onslow joined the 17 Destroyer Flotilla as leader.[17] On 24 November 1941, Onslow, together with sister ship Offa and the cruiser Berwick, joined Arctic convoy Convoy PQ 4, escorting the convoy until being relieved by locally based ships on 27 November. The convoy continued on to Arkhangelsk, while Berwick, Onslow and Offa proceeded to the naval base at Murmansk. They were attacked by German bombers on entering the Kola Inlet on 28 November, and Onslow was slightly damaged by a near miss.[17][19]

On 24 December,[c] Onslow set out from Scapa Flow together with the cruiser Kenya, the destroyers Offa, and Oribi and Chiddingfold and two landing ships as part of Operation Archery, a Combined Operations raid on the German-occupied Norwegian islands of Vågsøy and Måløy. The force arrived at its destination on 27 December, and while Commandos landed on the islands, Onslow and Oribi attacked a coastal convoy, sinking driving aground four merchant ships (Reimar Edward Fritzen, Norma, Eismeer and Anita M Russ) and boarding the Vorpostenboot (an armed trawler) Föhn, capturing coding wheels and bigram tables for the Enigma cypher machine, before sinking Föhn. More codebreaking material was captured later that day when Offa and Chiddingfold boarded and sunk the armed trawler Donner while sinking the cargo ship Anhalt.[21][22]

1942

On 1 January 1942, Onslow rescued 23 survivors from the British merchant ship Cardita, torpedoed the previous day by the German submarine U-87.[23] In early March 1942, Onslow sailed with the main body Home Fleet as part of the distant escort to the Arctic Convoys QP 8 and PQ 12. The Tirpitz sortied in an attempt to intercept one of the convoys, while the distant escort, including Onslow, searched for Tirpitz. Poor weather ensured that Tirpitz failed to find the convoy and the Home Fleet forces failed to find Tirpitz although the German battleship was later unsuccessfully attacked by aircraft from the carrier Victorious.[17][24][25] Later that month Onslow took part in similar distant escort operations for the Arctic Convoys PQ 13 and PQ 14.[26] On 21 May, the Arctic Convoy PQ 16 of 35 Merchant ships left Reykjavík in Iceland. It has an ocean escort of six destroyers and four corvettes, with a close covering force of three cruiser and the destroyers Onslow, Offa and Oribi joining on 23 May. The cruiser force, including Onslow left PQ 16 on 26 May to cover the westbound convoy QP 12. In total PQ 16 lost seven merchant ships before it reached Russian ports, while QP 12 was unharmed.[27][28]

In June 1942, much of the Home Fleet was detached to the Mediterranean to take part in Operation Harpoon, an attempt to run one supply convoy to Malta from the west, while a second convoy headed to Malta from Egypt (Operation Vigorous). Onslow was part of Force W, the covering force which also included the battleship Malaya, the aircraft carriers Argus and Eagle and three cruisers. Force W joined the Harpoon convoy shortly after it entered the Mediterranean on 12 June, and remained with it until turning back, as planned, as the convoy reached the Strait of Sicily on the evening of 14 June.[29][30] After her return to British waters, Onslow formed part of the distant escort for Arctic convoy PQ 17 and the return convoy QP 13. PQ 17 was ordered to be scattered and its close escort withdrawn based on mistaken intelligence that the Tirpitz was about to attack the convoy, which resulted in extremely heavy losses to the unprotected merchant ships, with 24 of the 25 merchant ships being sunk by German submarines and aircraft.[31][32] In August 1942, Onslow was employed in escorting units of the Home Fleet returning to British waters from Gibraltar after another Malta Convoy, Operation Pedestal.[23]

September 1942 saw the running of the next Arctic Convoy, PQ 18. The events of PQ 17 resulted in the decision to give the convoy a very strong escort. As well as the normal close escort, for most of the convoy's route it would be accompanied by the Escort carrier Avenger, and by a "Fighting Destroyer Escort" consisting of 16 destroyers led by the light cruiser Scylla. This force was backed up by a cruiser covering force, with more distant cover provided by the battleships of the Home Fleet.[33][34] Onslow formed part of the Fighting Destroyer Escort, which joined the convoy on 9 September.[35] The convoy came under heavy attack by German submarine and aircraft from 13 September,[36][37] and on 14 September a Swordfish aircraft from Avenger spotted the German submarine U-589 on the surface. Onslow was despatched against the submarine and carried out a series of depth charge attacks over three hours, sinking the submarine.[38][39][d] The carrier and Fighting Destroyer Escort remained with PQ 18 until 16 September, when it transferred to the westbound Convoy QP 14 to escort it through the area of most danger, with Onslow leaving QP 14 on 25 September.[41] In total, 13 ships out of 40 from PQ 18 were sunk, with the escort sinking three U-boats and claiming 41 German aircraft shot down. Three more merchant ships and a fleet oiler were lost from QP 14.[42]

On 8 November 1942, the British and Americans landed in French North Africa in Operation Torch,[43] with Onslow being employed in escorting follow-up convoys following the initial assault.[44]

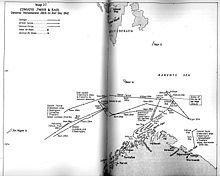

In December 1942, Onslow took part in Arctic Convoy JW 51B, joining the convoy on 25 December,[45] with Captain Robert Sherbrooke taking charge of the convoy's close escort of six destroyers, two corvettes, one minesweeper and two trawlers.[46][45][e] Five merchant ships, together with the destroyer Oribi and one of the trawlers, were separated from the convoy by bad weather shortly afterwards.[45] On 30 December, the convoy was spotted by the German submarine U-354, and in response a German force consisting of the heavy cruisers Lützow and Admiral Hipper and six destroyers set out from Altafjord to intercept the convoy.[45][47] The German force split into two, with Hipper and three destroyers attacking from the northwest and Lutzow and the other three destroyers from the south, with the intention that the escort would be drawn off to the first attacker, leaving the convoy unprotected. The Germans attacked on 31 December, in the Battle of the Barents Sea. Sherbrooke in Onslow led the other destroyers in dummy torpedo attacks against Hipper in order to force the cruiser to keep from closing, while laying a smoke-screen to protect the convoy. After about 40 minutes, Onslow was hit by three shells from Hipper and near missed by a fourth, and badly damaged. Two guns were put out of action[f] and a serious fire started, while 17 members of Onslow's crew were killed, and 23 wounded, including Sherbrooke.[51] Later, Achates sank after being hit by Hipper, and Obedient damaged, before the arrival of the British cruisers Sheffield and Jamaica changed the course of the battle, damaging Hipper and sinking the destroyer Friedrich Eckoldt before the Germans withdrew. The convoy had been saved, for the cost of the loss of Achates and the minesweeper Bramble. Sherbrooke was awarded the Victoria Cross for his actions in the battle.[52][53][54]

1943–45

After temporary repairs at Murmansk, Onslow returned to Britain as part of Convoy RA 52 at the end of January 1943,[55] then was repaired at a commercial shipyard in Kingston upon Hull, rejoining the fleet at the end of April that year.[23][50] In early November 1943, Onslow formed part of the distant escort for Convoy RA 54A on its return from Russia, and then took part in the close escort of Convoy JW 54A from 18 to 24 November and in the close escort of the return Convoy RA 54B from 28 November to 5 December, with none of the convoys being attacked by German forces.[56] From 22 to 29 December, Onslow formed part of the escort for Convoy JW 55B. An attempt by the German battleship Scharnhorst to attack the convoy resulted in the Battle of the North Cape on 26 December, when Scharnhorst was sunk by the battleship Duke of York. The convoy itself was not affected.[57] Onslow returned to Britain as part of the escort of Convoy RA 55B from 1 January to 7 January 1944.[58]

Onslow was refitted on the Tyne from 18 January to 22 February 1944.[50] In March, she carried out operations in the English Channel before returning to the Home Fleet to form part of the very strong escort for the Arctic Convoy JW 58 from 29 March to 4 April, and for the return convoy RA 58 from 7 to 13 April.[59] She was then again deployed to the Channel for patrol and escort duties in preparation for the upcoming invasion of France.[23] On the night of 27–28 April 1944, nine German S-boats (motor torpedo boats) attacked a convoy of American landing craft on exercise in Lyme Bay, sinking two and damaging another. Onslow, on patrol in the Channel, was diverted in an unsuccessful attempt to search for the German boats, followed by searching for survivors and bodies in Lyme Bay.[60][23] On 14 and 15 May 1944, Onslow formed part of the escort for the two aircraft carriers Emperor and Striker as they launched attacks against shipping in the ports of Rørvik and Stadlandet in German-occupied Norway, as part of a series of strikes by British aircraft carriers against Norway with the intention of distracting German attention from Northern France, as well as stopping German coastal shipping.[61][62]

The Invasion of Normandy on 6 June 1944, saw Onslow deployed in screening the invasion force as part of Operation Neptune.[63][64] On the night of 6/7 June, Onslow was near missed by a bomb, causing slight damage,[63][65] while on the night of 11/12 June, she was on patrol with Onslaught, Offa and Oribi when they clashed with a group of six German S-boats attempting to attack invasion shipping.[50][64][g] On 18 June, Onslow was hit by a German air-dropped torpedo which failed to explode, again causing slight damage, with the ship being under repair (from both this damage and that of 6/7 June) for 5 days.[63][66] On 12 August, Onslow, together with the cruiser Diadem and the destroyer Piorun sank the German auxiliary minesweeper Sperrbrecher 7 near La Rochelle.[67]

In September 1944, Onslow returned to duty with the Home Fleet, including continued duty on Arctic convoys.[23][50] From 22 October to 28 October, Onslow formed part of the escort of Convoy JW 61, and from 2 November to 7 November, part of the escort for the return convoy RA 61.[68][69] In December 1944, Onslow formed part of the escort for Convoy JW 62 and the return convoy RA 62.[70][71]

January 1945 gave a break from convoy duties, when on the night of 11/12 January, the cruisers Norfolk and Bellona, accompanied by the destroyers Onslow, Orwell and Onslaught carried out a sweep through Norwegian coastal waters. They attacked a German convoy off Egersund, sinking the minesweeper M-273 and shelling the merchant ships Bahia Camarones and Charlotte, which were abandoned and sank.[72] In February 1945, Onslow was part of the escort for Convoy JW 64, which came under heavy air and submarine attack, with 12 German bombers being lost in exchange for the corvette Denbigh Castle, which was torpedoed by U-992. The return convoy RA 64 was attacked by German submarines on leaving the Kola Inlet on 17 February, with the sloop Lark and the freighter Thomas Scott torpedoed and sunk by U-968, and the corvette Bluebell by U-711. Onslow rescued one man from Bluebell, the only survivor from the sinking.[73][74][23]

Post-War activities

On 12 May 1945, Onslow sailed as part of Convoy JW 67 to Russia, and on the return Convoy RA 67 which left the Kola Inlet on 23 May. Although the war in Europe had ended on 8 May, these last Arctic convoys were still provided with a substantial escort to guard against attacks from submarines that did not obey the German order to surrender.[75] On 5–7 June 1945, Onslow escorted the cruiser Norfolk, carrying King Haakon VII of Norway back from exile to Oslo.[23] In August 1945, Onslow attended the first British Navy week in a foreign port, in Rotterdam. Also there were the cruiser HMS Bellona, and the destroyer Garth as well as the submarine Tuna. Foreign vessels included two of the Dutch Navy submarines of the T-class, Dolfijn and Zeehond.[76]

In November–December 1945 she was the headquarter ship for Operation Deadlight, supervising the movement U-boats from Loch Ryan for scuttling off the coast of Ireland.[77] She was placed into Care and Maintenance status at Devonport in January 1946, with it being planned to use her as a target ship.[50]

Pakistan service

In 1948, the newly established Pakistan Navy sought to acquire two 4.7-inch gunned destroyers from Britain, and purchased Onslow and Offa for a total price of £605,000 for the two ships. Onslow was transferred to Pakistan on 30 September 1948 at Plymouth, becoming Tippu Sultan.[9][h] In 1954 she underwent a refit at Malta.[citation needed] Between 1957 and 1959 she underwent conversion to a Type 16 frigate by Grayson Rollo and Clover Docks at Birkenhead, England, with the conversion paid for by the US under the Mutual Defense Assistance Act.[50][11]

Tippu Sultan was active during the 1965 war with India, which broke out in September, taking part in a bombardment by the cruiser Babur and six destroyers of the Indian city of Dwarka on 8 September. She carried out patrols during the 1971 war. Tippu Sultan was stricken from the Pakistan Navy until 1980, after which her hull was used as a Hulk.[50]

Pennant numbers

| Pennant number | From | To |

|---|---|---|

| Royal Navy | ||

| G17[14] | 1941 | 1948 |

| Pakistan Navy | ||

| D47[11] | 1949 | 1957 |

| F249[11] | 1959 | 1963 |

| F260[11] | 1963 | - |

See also

Notes

- ^ 70 depth charges according to Conway's.[8]

- ^ It was decided to complete eight of the sixteen destroyers of the First and Second Emergency Flotilla with an armament of 4 inch (102 mm) guns rather than 4.7 inch (120 mm) guns. The 4.7 inch armed ships became the O-class and the 4-inch armed ships became the P-class, with several ships, including Onslow being renamed as a result.[16]

- ^ 26 December according to Sebag-Montefiore.[20]

- ^ Some sources credit U-589's sinking to Faulknor and say that Onslow sank U-88 on 12 September.[40]

- ^ Destroyers: Onslow, Obedient, Obdurate, Oribi, Orwell and Achates, Corvettes: Rhododendron and Hyderabad, Minesweeper: Bramble, Trawlers: Vizalma and Northern Gem.[45]

- ^ While H.M. Ships Damaged or Sunk by Enemy Action and Roskill say that two guns were knocked out,[48][49] English says that one gun ('B' mount) was knocked out and one ('A' mount) could only be fired under local control.[50]

- ^ This engagement took part on the night of 12/13 June according to Winser.[63]

- ^ In fact she remained HMS Tippu Sultan for some years, prior to renaming later in 1952-53. See documents and photograph of Mr A. Salim Khan, Pakistan's First Charge d'Affaires to Japan, and his voyage on this ship from the United States to Yokohama, in the Begum Mahmooda Salim Khan Collection/Papers, Accession Ref.No. 224-BMS, at the National Archives of Pakistan, Islamabad, website for further information http://www.nap.gov.pk Archived 5 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine

Citations

- ^ a b c Whitley 2000, p. 124

- ^ Lenton 1970, p. 3

- ^ a b c d Lenton 1970, p. 5

- ^ Lenton 1970, pp. 3, 5

- ^ Friedman 2008, pp. 54–55, 57, 94

- ^ a b c Friedman 2008, p. 57

- ^ English 2008, p. 13

- ^ Gardiner & Chesneau 1980, p. 42

- ^ a b English 2008, pp. 18, 22

- ^ English 2008, p. 15

- ^ a b c d e Blackman 1971, p. 251

- ^ English 2008, p. 10

- ^ English 2008, p. 11

- ^ a b c d Friedman 2008, p. 327

- ^ a b c English 2008, p. 206

- ^ English 2008, pp. 11–12

- ^ a b c d e English 2008, p. 21

- ^ Whitley 2000, p. 125

- ^ Ruegg & Hague 1993, p. 23

- ^ Sebag-Montefiore 2000, p. 192

- ^ Rohwer & Hümmelchen 1992, pp. 110–111

- ^ Sebag-Montefiore 2000, pp. 191–196

- ^ Ruegg & Hague 1993, pp. 27–29

- ^ Rohwer & Hümmelchen 1992, p. 128

- ^ Ruegg & Hague 1993, pp. 29, 31

- ^ Ruegg & Hague 1993, pp. 37–39

- ^ Rohwer & Hümmelchen 1992, p. 141

- ^ Rohwer & Hümmelchen 1992, pp. 145–146

- ^ Barnett 2000, pp. 505–509

- ^ Ruegg & Hague 1993, pp. 39–41

- ^ Rohwer & Hümmelchen 1992, pp. 147–148

- ^ Roskill 1956, p. 280

- ^ Barnett 2000, pp. 723–725

- ^ Ruegg & Hague 1993, p. 43

- ^ Rohwer & Hümmelchen 1992, p. 163

- ^ Barnett 2000, pp. 726–727

- ^ Kemp 1997, pp. 89–90

- ^ Helgason, Guðmundur. "U-589". uboat.net. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- ^ Blair 2000, p. 20

- ^ Ruegg & Hague 1993, pp. 44–45

- ^ Barnett 2000, pp. 727–728

- ^ Rohwer & Hümmelchen 1992, pp. 174–175

- ^ Winser 2002, pp. 67, 70

- ^ a b c d e Ruegg & Hague 1993, p. 48

- ^ Roskill 1956, p. 291

- ^ Rohwer & Hümmelchen 1992, p. 184

- ^ H.M. Ships Damaged or Sunk by Enemy Action 1952, p. 225

- ^ Roskill 1956, p. 295

- ^ a b c d e f g h English 2008, p. 22

- ^ Roskill 1956, pp. 292–295

- ^ Roskill 1956, pp. 295–298

- ^ Ruegg & Hague 1993, p. 49

- ^ "No. 35859". The London Gazette (Supplement). 8 January 1943. pp. 283–284.

- ^ Ruegg & Hague 1993, p. 52

- ^ Ruegg & Hague 1993, pp. 55–57

- ^ Ruegg & Hague 1993, pp. 57–58

- ^ Ruegg & Hague 1993, p. 59

- ^ Ruegg & Hague 1993, pp. 63–64

- ^ Rohwer & Hümmelchen 1992, p. 270

- ^ Rohwer & Hümmelchen 1992, p. 274

- ^ Roskill 1960, pp. 278–279

- ^ a b c d Winser 1994, p. 106

- ^ a b Rohwer & Hümmelchen 1992, p. 281

- ^ H.M. Ships Damaged or Sunk by Enemy Action 1952, p. 256

- ^ H.M. Ships Damaged or Sunk by Enemy Action 1952, p. 258

- ^ Rohwer & Hümmelchen 1992, p. 295

- ^ Ruegg & Hague 1993, pp. 67–69

- ^ Rohwer & Hümmelchen 1992, pp. 312–313

- ^ Ruegg & Hague 1993, pp. 69–70

- ^ Rohwer & Hümmelchen 1992, p. 318

- ^ Rohwer & Hümmelchen 1992, p. 328

- ^ Ruegg & Hague 1993, pp. 73–74

- ^ Rohwer & Hümmelchen 1992, pp. 333–334

- ^ Ruegg & Hague 1993, pp. 78–79

- ^ "British Navy Week in Rotterdam". The Times. No. 50223. 17 August 1945. p. 6.

- ^ Critchley 1982, p. 14

References

- Barnett, Correlli (2000). Engage the Enemy More Closely. Classic Penguin. ISBN 0-141-39008-5.

- Blackman, Raymond V. B., ed. (1971). Jane's Fighting Ships 1971–72. London: Sampson Low, Marston & Co., Ltd. ISBN 0-354-00096-9.

- Blair, Clay (2000). Hitler's U-Boat War: The Hunted, 1942–1945. New York: Modern Library. ISBN 0-679-64033-9.

- Colledge, J. J.; Warlow, Ben (2006) [1969]. Ships of the Royal Navy: The Complete Record of all Fighting Ships of the Royal Navy (Rev. ed.). London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 978-1-86176-281-8.

- Critchley, Mike (1982). British Warships Since 1945: Part 3: Destroyers. Liskeard, UK: Maritime Books. ISBN 0-9506323-9-2.

- English, John (2008). Obdurate to Daring: British Fleet Destroyers 1941–1945. Windsor, UK: World Ship Society. ISBN 978-0-9560769-0-8.

- Friedman, Norman (2008). British Destroyers & Frigates: The Second World War and After. Barnsley, UK: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84832-015-4.

- Gardiner, Robert; Chesneau, Roger, eds. (1980). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1922–1946. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-146-7.

- H.M. Ships Damaged or Sunk by Enemy Action: 3rd. SEPT. 1939 to 2nd. SEPT. 1945. Admiralty. 1952. Retrieved 21 January 2019.

- Kemp, Paul (1997). U-Boats Destroyed: German Submarine Losses in the World Wars. London: Arms & Armour Press. ISBN 1-85409-321-5.

- Lenton, H. T. (1970). Navies of the Second World War: British Fleet and Escort Destroyers: Volume Two. London. ISBN 0-356-03122-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Lenton, H. T. (1998). British & Empire Warships of the Second World War. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-048-7.

- Raven, Alan & Roberts, John (1978). War Built Destroyers O to Z Classes. London: Bivouac Books. ISBN 0-85680-010-4.

- Rohwer, Jürgen; Hümmelchen, Gerhard (1992). Chronology of the War at Sea 1939–1945. London: Greenhill Books. ISBN 1-85367-117-7.

- Roskill, S. W. (1956). The War at Sea 1939–1945: Volume II: The Period of Balance. History of the Second World War: United Kingdom Military Series. London: HMSO – via Hyperwar.

- Roskill, S. W. (1960). The War at Sea 1939–1945: Volume III: The Offensive Part I, 1st June 1943–31st May 1944. History of the Second World War: United Kingdom Military Series. London: HMSO.

- Roskill, S. W. (1961). The War at Sea 1939–1945: Volume III: The Offensive Part II, 1st June 1944–14th August 1945. History of the Second World War: United Kingdom Military Series. London: HMSO.

- Ruegg, Bob; Hague, Arnold (1993). Convoys to Russia: 1941–1945. Kendal, UK: World Ship Society. ISBN 0-905617-66-5.

- Sebag-Montefiore, Hugh (2000). Enigma: The Battle for the Code. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-84251-X.

- Whitley, M. J. (2000). Destroyers of World War Two: An International Encyclopedia. London: Cassell & Co. ISBN 1-85409-521-8.

- Winser, John de S. (2002). British Invasion Fleets: The Mediterranean and beyond 1942–1945. Gravesend, UK: World Ship Society. ISBN 0-9543310-0-1.

- Winser, John de S. (1994). The D-Day Ships. Kendal, UK: World Ship Society. ISBN 0-905617-75-4.

Further reading

- Connell, G. G. (1982). Arctic Destroyers: The 17th Flotilla. London: William Kimber. ISBN 0-7183-0428-4.