Turkish art

Turkish art (Turkish: Türk sanatı) refers to all works of visual art originating from the geographical area of what is present day Turkey since the arrival of the Turks in the Middle Ages.[citation needed] Turkey also was the home of much significant art produced by earlier cultures, including the Hittites, Ancient Greeks, and Byzantines. Ottoman art is therefore the dominant element of Turkish art before the 20th century, although the Seljuks and other earlier Turks also contributed. The 16th and 17th centuries are generally recognized as the finest period for art in the Ottoman Empire, much of it associated with the huge Imperial court. In particular the long reign of Suleiman the Magnificent from 1520 to 1566 brought a combination, rare in any ruling dynasty, of political and military success with strong encouragement of the arts.[1]

The nakkashane, as the palace workshops are now generally known, were evidently very important and productive, but though there is a fair amount of surviving documentation, much remains unclear about how they operated. They operated over many different media, but apparently not including pottery or textiles, with the craftsmen or artists apparently a mixture of slaves, especially Persians, captured in war (at least in the early periods), trained Turks, and foreign specialists. They were not necessarily physically located in the palace, and may have been able to undertake work for other clients as well as the sultan. Many specialities were passed from father to son.[2]

Seljuk period

The Seljuks of Rum, who rose to power in Anatolia during the late 11th century, ruled a multi-ethnic territory that was only recently settled by Muslims. As a result, their architecture was eclectic and incorporated influences from many cultures in the region.[3] Most Anatolian Seljuk buildings are constructed of dressed stone, with brick reserved for minarets. The use of stone in Anatolia is the biggest difference with the Seljuk buildings in Iran, which are made of bricks. This also resulted in more of their monuments being preserved up to modern times.[4] In their construction of caravanserais, madrasas and mosques, the Anatolian Seljuks translated earlier Iranian Seljuk architecture of bricks and plaster into the use of stone.[5]

Decoration in Anatolian Seljuk architecture was concentrated on certain elements like entrance portals, windows, and the mihrabs of mosques. Stone-carving was one of the most accomplished mediums of decoration, with motifs ranging from earlier Iranian stucco motifs to local Byzantine and Armenian motifs. Muqarnas was also used. The madrasas of Sivas and the Ince Minareli Medrese in Konya are among the most notable examples, while the Great Mosque and Hospital complex of Divriği is distinguished by the most extravagant and eclectic high-relief stone decoration around its entrance portals and its mihrab. Syrian-style ablaq striped marble also appears on the entrance portal of the Karatay Medrese and the Alaeddin Mosque in Konya. Although tilework was commonly used in Iran, Anatolian architecture innovated in the use of tile revetments to cover entire surfaces independently of other forms of decoration, as seen in the Karatay Medrese.[7][8]

Ottoman period

Ottoman architecture developed traditional Islamic styles, with some technical influences from Europe, into a highly sophisticated style, with interiors richly decorated in coloured tiles, seen in palaces, mosques and turbe mausolea.[9]

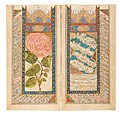

Other forms of art represented developments of earlier Islamic art, especially those of Persia, but with a distinct Turkish character. As in Persia, Chinese porcelain was avidly collected by the Ottoman court, and represented another important influence, mainly on decoration.[10] Ottoman miniature and Ottoman illumination cover the figurative and non-figurative elements of the decoration of manuscripts, which tend to be treated as distinct genres, though often united in the same manuscript and page.[11]

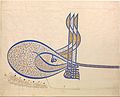

The reign of the Ottomans in the 16th and early 17th centuries introduced the Turkish form of Islamic calligraphy. This art form reached the height of its popularity during the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent (1520–66).[12] As decorative as it was communicative, Diwani was distinguished by the complexity of the line within the letter and the close juxtaposition of the letters within the word. The hilya is an illuminated sheet with Islamic calligraphy of a description of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. The tughra is an elaborately stylized formal signature of the sultan, which like the hilya performed some of the functions of portraits in Christian Europe. Book covers were also elaborately decorated.[13]

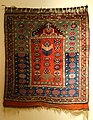

Other important media were in the applied or decorative arts rather than figurative work. Pottery, especially İznik pottery, jewellery, hardstone carvings, Turkish carpets, woven and embroidered silk textiles were all produced to extremely high standards, and carpets in particular were exported widely. Other Turkish art ranges from metalwork, carved woodwork and furniture with elaborate inlays to traditional Ebru or paper marbling.[14]

18th to 20th centuries

In the 18th and 19th centuries Turkish art and architecture became more heavily influenced by contemporary European styles, leading to over-elaborated and fussy detail in decoration.[15] European-style painting was slow to be adopted, with Osman Hamdi Bey (1842–1910) for long a somewhat solitary figure. He was a member of the Ottoman administrative elite who trained in Paris, and painted throughout his long career as a senior administrator and curator in Turkey. Many of his works represent the subjects of Orientalism from the inside, as it were.

20th century and onward

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Turkey |

|---|

|

| Languages |

| Mythology and folklore |

| Cuisine |

| Religion |

| Art |

| Literature |

A transition from Islamic artistic traditions under the Ottoman Empire to a more secular, Western orientation has taken place in Turkey. Modern Turkish painters are striving to find their own art forms, free from Western influence. Sculpture is less developed, and public monuments are usually heroic representations of Atatürk and events from the war of independence. Literature is considered the most advanced of contemporary Turkish arts.

Repatriation of looted art

In 2024, a bronze statue of the head of a youth was returned to Turkey by the J. Paul Getty Museum[16] and a bronze statue of the head of Roman Emperor Septimius Severus was to be returned to Turkey by Denmark's NY Carlsberg Glypotek Museum. Originating in the ancient city of Boubon in Burdur, they were looted in illegal excavations in the 1960s.[17][18] Turkey requested that the Cleveland Museum of Art return 21 objects[19] [20][21] but the museum refused saying the Turkey lacked proof of looting[22] causing a clash with the Manhattan District Attorney and the unit that fights Antiquities Trafficking.[23][24]

Gallery

Architecture

- Entrance of the Çifte Minareli Medrese in Erzurum (c. 1250)

- Entrance of the Divriği Mosque, Sivas (c. 1229)

- Imperial Hall in Harem of Topkapı Palace in Istanbul

- Istanbul Yalı architecture

- An example of the Yalı architecture

- Safranbolu, an Ottoman village

- Interior of a dome at Dolmabahçe Palace

- Mihrab niche of Bursa Grand Mosque

- Cross section and plan of Bayezid II Mosque, the oldest imperial complex in Istanbul that is preserved in more or less its original form

- Exterior design of Selimiye Mosque, Edirne

- Interior decoration of the dome of Selimiye Mosque, Edirne

- Old Fatih Municipality Building

- Liman Han (inn)

Calligraphy

- Sample training of Abdul Rahman Hilmi, ink, colours and gold on paper

- Gold illuminated two opening chapters of the Holy Koran by Mehmed Şevki Efendi

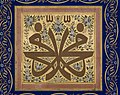

- Decorated tughra of Suleyman the Magnificent (1520)

- A decree with royal tughra on top for appointing second imam in the Mehmed Sultan Mosque in Ohrid, Republic of Macedonia

- Main dome of the Blue Mosque with calligraphy inscriptions

- The testimony of faith (top) and tughras (right and left) inscribed on the entrance to a building at Topkapi Palace, Istanbul

Carpets

- Anatolian double-niche rug, Konya region, circa 1750–1800

- Bergama rug

Culinary art

Dance

- A modern Ottoman military band (mehter) troop

- A traditional Turkish folk dance team

- Turkish Belly Dance at the 18th International Folklore Festival, 2012, Plovdiv, Bulgaria

- A children's folk dance team from the Black Sea region

- Turkish dance group

- Turkish dance group

- Zeybek Dancer

Fashion

- Sultan Abdul Majid, Pera Museum

- Turkish model at a fashion show, Brussels, Belgium

- Turkish model at a fashion show, Brussels, Belgium

- Military Pictures from the Ralamb Costume Book, 1657

- Women's dress, late 1800s, Syria (right) and coat from early 1900s, silk and cotton (left), exhibit in the Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum, Cologne, Germany

- Historical Turkish costumes, 1880s, Smithsonian Libraries

- Ashjibashi (head cook) of the Janissaries in ceremonial uniform

- The Kul Kethüdası, commander of the third division of the Janissaries

- Silahdar Agha, sword-bearer of the Sultan

- A Şehzade, Ottoman prince of the blood

Handcraft

- Minbar of the Alaeddin Mosque in Konya, dated to 1155–1156. This minbar is a prime example of the kündekâri technique, in which many interlocking pieces of wood are held together without the use of nails, pins, or glue

- Individual pieces are carved with vegetal arabesque motifs within the wider geometric motif formed by the different pieces

- Front part of Alaeddin Mosque's minbar

- The carved wood minbar of the Divriği Great Mosque and Hospital in Sivas, an example of Seljuk handicraft

- Detail of the Divriği minbar: the lines between the wooden boards mounted side-by-side are visible, while the surface itself is carved with motifs imitating kündekâri work

- Minbar of the Great Mosque of Siirt (13th century), now housed in the Ethnography Museum of Ankara

- Stained glass windows at Topkapı Palace

- A room at Topkapı Palace, carpet with a small-pattern "Holbein" design

Illumination

- Single-volume Qur’an. Copied by Khalil Allah ibn Mahmud Shah, illuminated by Muhammad ibn Ali

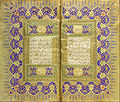

- Page from Ottoman Qur'an. Ink, color, and gold on paper. Probably Edirne

- Hilye-i Şerif Anthology, early 19th century in Sadberk Hanım Museum

- Qur'an copied by Abdullah Zühdi

- The name 'Muhammad' is written in mirrored thuluth script, and filled with Qur'anic verses in ghubar

- Hilye-i Şerif. Unknown, Ottoman, circa 1725 in Sadberk Hanım Museum

- "Divan-i Muhibbi",Calligraphy in nastaliq by Mehmed Şerif, illumination by Kara Memi, Istanbul, 1566

Miniature

- An Ottoman official miniature

- Miniature depiction of the Battle of Mezőkeresztes, Hungary (1596)

- Capture of Buda (1526)

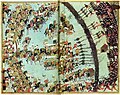

- Miniature depicting the Siege of Nice, France (1543) by Matrakçı Nasuh

- 16th century map of Miyaneh by Matrakçı Nasuh

- Selim II ascends to the throne

- Topkapı Palace during the reign of Selim I

- Use of fireworks during the celebrations.

- Acrobats during celebrations

- Ships of parade

Painting

- Two Musician Girls by Osman Hamdi Bey

- The Tortoise Trainer by Osman Hamdi Bey, 1906

- Work by Osman Hamdi Bey

- Arzuhalci by Osman Hamdi Bey

Sculpture

- Güzel İstanbul by Gürdal Duyar

- Akdeniz by İlhan Koman

- Water Swirl by İlhan Koman

- Statue of Humanity by Mehmet Aksoy

- Efenin Aşkı by Hüseyin Gezer

Tiles

- Cem Sultan tomb in Bursa, the first official capital of the Ottoman Empire

- Tiles of the circumcision room at Topkapi Palace

- Tiles of the circumcision room at Topkapi Palace

- The entrance to the Harem at Topkapi Palace

- Eunuchs' Courtyard in Harem of Topkapı Palace

- Tile decoration on the Dome of the Rock, added during Sultan Suleiman's reign

- Tiles of the Rüstem Pasha Mosque

- Tiles of the Rüstem Paşa Mosque

- Tiles of the Rüstem Paşa Mosque

- Iznik (ancient Nicea) tiles

- Tiles of the Imperial Council Second Courtyard

Weapons

- An Ottoman horse archer

- Ottoman Mamluk horseman with mail and plate armour, 1550

- Jeweled Ottoman sabres

- Kilij sword was in use from the early 17th century, for more than 300 years, well into the 20th century.

- Ottoman yataghan sword, 19th century or earlier.

- Decorated Ottoman cannon, 1581

- Ottoman rifles, 1750-1800

See also

- Turkish and Islamic Arts Museum

- Culture of the Ottoman Empire

- Ottoman clothing

- Islamic calligraphy

- List of Ottoman calligraphers

- History of Modern Turkish painting

- Turkish women in fine arts

Notes

- ^ Levey, 12; Rogers and Ward, throughout, especially 26–41

- ^ Rogers and Ward, 120–124; 186–188

- ^ Ettinghausen, Grabar & Jenkins-Madina 2001, p. 234.

- ^ Hattstein & Delius 2011, p. 371.

- ^ Blair & Bloom 2004, p. 130.

- ^ Kuban, Doğan (2001). The Miracle of Divriği: An Essay on the Art of Islamic Ornamentation in Seljuk Times. Istanbul: YKY. pp. 27–32. ISBN 975080290X.

- ^ Ettinghausen, Grabar & Jenkins-Madina 2001, p. 241.

- ^ Bloom, Jonathan M.; Blair, Sheila S., eds. (2009). "Architecture; V. c. 900–c. 1250; C. Anatolia". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. pp. 117–120. ISBN 9780195309911.

- ^ Levey, throughout

- ^ Levey, 54, 60; Rogers and Ward, 29, 186; Rawson, 183–191, and see index

- ^ Levey, see index; Rogers and Ward, 59–119

- ^ Rogers and Ward, 55–74

- ^ Levey, see index; Rogers and Ward, 26–41, 62–64 on tughra

- ^ Rogers and Ward, 120–215, cover a wide range; Levey, 51–55, and see index

- ^ Levey, chapters 5 and 6

- ^ "Getty Museum Agrees to Return Ancient Bronze Head to Turkey". nytimes.com.

The J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles on Wednesday said it was returning an ancient bronze head to Turkey that it had purchased in 1971 from an antiquities dealer who sold other items to museums that were later found to have been looted. The museum said the decision was made "in light of new information" provided by the Manhattan district attorney's office, which asserts that the object was stolen in the 1960s from a heavily plundered Roman-era settlement in Turkey known as Bubon.

- ^ Wells, Elizabeth (2023-07-05). "Turkey seeks return of 'stolen' severed statue head". CNN. Retrieved 2024-11-27.

- ^ AFP, Agence France-Presse- (2024-11-26). "Denmark to return head of Roman emperor's statue to Türkiye". Daily Sabah. Retrieved 2024-11-27.

- ^ "Turkey Requests at Cleveland Museum of Art | PDF | Anatolia | Turkey". Scribd. Retrieved 2024-11-27.

- ^ Felch, Jason; Times, Los Angeles (2012-03-30). "Turkey asks U.S. museums for return of antiquities". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2024-11-27.

- ^ "Turkey turns up the heat on foreign museums as list of antiquities demanded gets longer". The Art Newspaper - International art news and events. 2012-05-31. Retrieved 2024-11-27.

- ^ Steven Litt, cleveland com (2012-05-27). "Turkey's inquiry into 22 treasures at the Cleveland Museum of Art lacks hard proof of looting". cleveland. Retrieved 2024-11-27.

- ^ "Bronze Roman statue, believed to have been looted from Turkey, seized from Cleveland Museum of Art". The Art Newspaper - International art news and events. 2023-08-31. Retrieved 2024-11-27.

- ^ Schrader, Adam (2023-10-20). "The Cleveland Museum of Art Is Suing the Manhattan D.A. Over the Seizure of a $20 Million Statue Allegedly Looted From Turkey". Artnet News. Retrieved 2024-11-27.

References

- Blair, Sheila; Bloom, Jonathan (2004). "West Asia:1000-1500". In Onians, John (ed.). Atlas of World Art. Laurence King Publishing.

- Ettinghausen, Richard; Grabar, Oleg; Jenkins-Madina, Marilyn (2001). Islamic Art and Architecture: 650–1250. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-08869-4. Retrieved 2013-03-17.

- Hattstein, Markus; Delius, Peter, eds. (2011). Islam: Art and Architecture. H. F. Ullman. ISBN 9783848003808.

- Levey, Michael; The World of Ottoman Art, 1975, Thames & Hudson, ISBN 0500270651

- Rawson, Jessica, Chinese Ornament: The Lotus and the Dragon, 1984, British Museum Publications, ISBN 0714114316

- Rogers J.M. and Ward R.M.; Süleyman the Magnificent, 1988, British Museum Publications ISBN 0714114405

Further reading

- Binney, Edwin. Turkish Miniature Paintings and Manuscripts, from the Collection of Edwin Binney, 3rd. New York City: Metropolitan Museum of Art; Los Angeles, Calif.: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1973. 139 p., amply ill. (in b&w). N.B.: Catalogue of an exhibition held at the named museums. ISBN 0-87099-077-2

- Miller, Lenore D. Echoes of Anatolia: Works of Contemporary Turkish-American Artists ... [catalogue of an] Exhibition [which] Has Been Realized through the Generosity of the Contributing Artists and [of] the Turkish Embassy in Washington, D.C. [Washington, D.C., c. 1987]. 24 p., amply ill. (in black and white). Without ISBN