Bass drum

An orchestral bass drum A pedal bass drum, or kick drum | |

| Percussion instrument | |

|---|---|

| Classification | Percussion |

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | 211.212.1 (Individual double-skin cylindrical drums) |

| Developed | Turkey |

| Playing range | |

| |

The bass drum is a large drum that produces a note of low definite or indefinite pitch. The instrument is typically cylindrical, with the drum's diameter usually greater than its depth, with a struck head at both ends of the cylinder. The heads may be made of calfskin or plastic and there is normally a means of adjusting the tension, either by threaded taps or by strings. Bass drums are built in a variety of sizes, but size does not dictate the volume produced by the drum. The pitch and the sound can vary much with different sizes,[2] but the size is also chosen based on convenience and aesthetics. Bass drums are percussion instruments that vary in size and are used in several musical genres. Three major types of bass drums can be distinguished.

- The type usually seen or heard in orchestral, ensemble or concert band music is the orchestral, or concert bass drum (in Italian: gran cassa, gran tamburo). It is the largest drum of the orchestra.

- The kick drum, a term for a bass drum associated with a drum kit, which is much smaller than the above-mentioned bass drum. It is struck with a beater attached to a pedal, usually seen on drum kits.

- The pitched bass drum, generally used in marching bands and drum corps, is tuned to a specific pitch and is usually played in a set of three to six drums.

In many forms of music, the bass drum is used to mark or keep time. The bass drum makes a low, boom sound when the mallet hits the drumhead. In marches, it is used to project tempo (marching bands historically march to the beat of the bass). A basic beat for rock and roll has the bass drum played on the first and third beats of bars in common time, with the snare drum on the second and fourth beats, called backbeats. In jazz, the bass drum can vary from almost entirely being a timekeeping medium to being a melodic voice in conjunction with the other parts of the set.

Etymology

Bass drums have many synonyms and translations, such as gran cassa (It), grosse caisse (Fr), Grosse Trommel or Basstrommel (Ger), and bombo (Sp).[2]

History

The earliest known predecessor to the bass drum was the Turkish davul, a cylindrical drum that featured two thin heads. The heads were stretched over hoops and then attached to a narrow shell.[3][4] To play this instrument, a person would strike the right side of the davul with a large wooden stick, while the left side would be struck with a rod.[5] When struck, the davul produced a sound much deeper than that of the other drums in existence. Because of this unique tone, davuls were used extensively in war and combat, where a deep and percussive sound was needed to ensure that the forces were marching in proper step with one another.[6] The military bands of the Ottoman Janissaries in the 18th century were one of the first groups to utilize davuls in their music; Ottoman marching songs often had a heavy emphasis on percussion, and their military bands were primarily made up of davul, cymbal and kettle drum players.[5]

Davuls were ideal for use as military instruments because of the unique way in which they could be carried. The Ottoman janissaries, for example, hung their davuls at their breasts with thick straps.[3] This made it easier for the soldiers to carry their instruments from battle to battle. This practice does not seem to be limited to just the Ottoman Empire, however; in Egypt, drums very similar to davuls were braced with cords, which allowed the Egyptian soldiers to carry them during military movements.[3]

The davul, however, was also used extensively in non-military music. For example, davuls were a major aspect of Turkish folk dances.[7] In Ottoman society, davul and shawm players would perform together in groups called davul-zurnas, or drum and shawm circles.[7]

- Long drums

At its peak, the Ottoman Empire stretched from Vienna down to northern Africa and most of the middle east.[8] This long reach meant that many aspects of Ottoman culture, including the davul and other janissary instruments, were likely introduced to other parts of the world. In Africa, the indigenous population took the basic idea of the davul – that is, a two-headed cylindrical drum that produces a deep sound when struck – and both increased the size of the drum and changed the material from which it was made, leading to the development of the long drum.[3] The long drum can be made in a variety of different ways but is most typically constructed from a hollowed-out tree trunk. This is vastly different from the davul, which is made from a thick shell.[9] Long drums were typically 2 meters in length and 50 centimeters in diameter, much larger than the Turkish drums on which they were based. The indigenous population also believed that the tree from which the long drum was made had to be in perfect shape. Once an appropriate tree was selected and the basic frame for the long drum was constructed, the Africans took cow hides and soaked them in boiling hot water, in order to stretch them out.[9] Although the long drum was an improvement on the davul, both drums were nevertheless played in a similar fashion. Two distinct sticks were used on the two distinct sides of the drum itself. A notable difference between the two is that long drums, unlike davuls, were used primarily for religious purposes.[9]

- Gong drums

As the use of the long drum began to spread across Europe, many composers and musicians started looking for even deeper tones that could be used in compositions. As a result of this demand, a narrow-shelled, single-headed drum called the gong drum was introduced in Britain during the 19th century.[3] This drum, which was 70-100 centimeters in diameter and deep-shelled, was similar to the long drum in both size and construction. When struck, the gong drum produced a deep sound with a rich resonance. However, the immense size of the drum, coupled with the fact that there was not a second head to help balance the sound, meant that gong drums tended to produce a sound with a definite pitch. As a result, they fell out of favor with many composers, as it became nearly impossible to incorporate them in an orchestra in any meaningful way.[3][5]

- Orchestral bass drums and drum kits

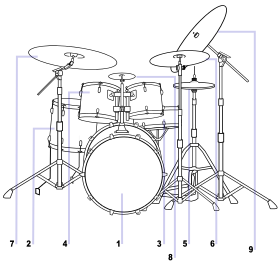

| The drum kit |

|---|

|

| Not shown |

| See also |

Because they were unable to be used by orchestras, music makers began to build smaller gong drums that would not carry a definite pitch. This smaller version of the gong drum is today called the orchestral bass drum, and it is the prototype with which people are most familiar today. The modern bass drum is used primarily in orchestras. The drum, similar to the davul and long drum, is double-headed, rod tensioned and measures roughly 40 inches in diameter and 20 inches in width.[3] Most orchestral bass drums are situated within a frame, which allows them to be positioned at any angle.[3]

Bass drums are also highly visible in modern drum kits. In 1909, William Ludwig created a workable bass drum pedal, which would strike a two-headed bass drum in much the same way as a drumstick.[10] During the 1960s, many rock ‘n’ roll drummers began incorporating more than one bass drum in their drum kit, including the Who's Keith Moon and Cream's Ginger Baker.[3][10]

Classical music

In classical music, composers have much more freedom in the way the bass drum is used than in other genres of music. Common uses are:

- Providing local "colour"[2]

- Climactic single strokes[2]

- Rolls[2]

- Adding weight to loud tutti sections

Apart from the standard beaters mentioned above, implements used to strike the drum may include keyboard percussion mallets, timpani mallets, and drumsticks. The hand or fingers can also be used (it. con la mano). The playing techniques possible include rolls, repetitions and unison strokes. Bass drums can sometimes be used for sound effects. e.g. thunder, or an earthquake.[5]

Mounting

Bass drums are too large to be handheld and are always mounted in some way. The usual ways of mounting a bass drum are:

- Using a shoulder harness so that the heads are vertical

- On a floor stand as part of a drum kit. The heads are always vertical when mounted in this way.

- On an adjustable cradle. In this situation, the heads may be adjusted to any position between vertical and horizontal.

- It is possible for the bass drum to have a single cymbal mounted on it[2]

Strikers

Bass drums can have a variety of strikers depending on the music:

- A single heavy felt covered mallet (Fr. Mailloche; It. Mazza).[2]

- When the drum is mounted vertically, the malet above may be held in one hand and a rute held in the other.[2]

- 2 matching bass drum mallets or a double headed mallet are used for playing drum rolls.[2]

- When used as part of a drum kit, a variation of the mallet described above is mounted on a pedal and called a beater.

Electronic music

In electronic music, bass drums, especially kick drums, are frequently used. Kick drum sounds are prominent in various music styles, including American genres like footwork and African genres such as gqom.[4][6][8]

Kit drumming

In a drum kit, the bass drum is much smaller than in traditional orchestral use, most commonly 20 or 22 inches (51 or 56 centimetres) in diameter. Sizes range from 16 to 28 inches (41 to 71 centimetres) in diameter while depths range from 12 to 22 inches (30 to 56 centimetres), with 14 to 18 inches (36 to 46 centimetres) being normal. Vintage bass drums are generally shallower than the current standard of 22 in × 18 in (56 cm × 46 cm).

Sometimes the front head of a kit bass drum has a hole in it to allow air to escape when the drum is struck for shorter sustain. Muffling can be installed through the hole without taking off the front head. The hole also allows microphones to be placed into the bass drum for recording and amplification. In addition to microphones, sometimes trigger pads are used to amplify the sound and provide a uniform tone, especially when fast playing without a decrease in volume is desired. Professional drummers often choose to have a customized bass drum front head, with the logo or name of their band on the front.

The kit bass drum may be more heavily muffled than the classical bass drum, and it is popular for drummers to use a pillow, blanket, or professional mufflers[11] inside the drum, resting against the batter head, to dampen the blow from the pedal, and produce a shorter "thud".

Different beaters have different effects, and felt, wood and plastic ones are all popular. Bass drums sometimes have a tom-tom mount on the top, to save having to use (and pay for) a separate stand or rack. Fastening the mount involves cutting a hole in the top of the bass drum to attach it; "virgin" bass drums do not have this hole cut in them, and so are professionally prized.

Bass drum pedal

In 1900, Sonor drum company introduced its first single bass drum pedal. William F. Ludwig made the bass drum pedal workable in 1909, paving the way for the modern drum kit.[12] A bass drum pedal operates much the same as the hi-hat control; a footplate is pressed to pull a chain, belt, or metal drive mechanism downward, bringing a beater or mallet forward into the drumhead. The beater head is usually made of either felt, wood, plastic, or rubber and is attached to a rod-shaped metal shaft. The pedal and beater system are mounted in a metal frame and like the hi-hat, a tension unit controls the amount of pressure needed to strike and the amount of recoil upon release.

Double bass drum pedal

A double bass drum pedal operates much the same way as a single bass drum pedal does, but with a second footplate controlling a second beater on the same drum. Most commonly this is attached by a shaft to a remote beater mechanism alongside the primary pedal mechanism.[13][14] One notable exception to this pattern is the symmetrical Sleishman twin bass drum pedal.

Alternatively, some drummers opt for two separate bass drums with a single pedal on each, for a similar effect.

Drop-clutch

When using a double bass drum pedal, the foot which normally controls the hi-hat pedal moves to the second bass drum pedal, and so the hi hat opens and remains open. A drop clutch can be used to keep the hi-hat in the closed position, even with the foot removed from the pedal.

Pedal techniques

There are 3 primary ways to play single strokes with one foot. The first is heel-down technique, where the player's heel is planted on the pedal and the strokes are played with the ankle. This stroke is good for quiet playing and quick syncopated rhythms. The next technique is heel-up, where the player's heel is lifted off of the pedal and the strokes originate from the hip. The ankle is still flexed with each stroke, but the full weight of the leg can be used to add additional power for louder playing situations. Lifting the heel allows access to several double stroke techniques as well. The third primary technique is the floating stroke where the heel is lifted off the pedal as in heel-up, but the stroke is played primarily from the ankle as in heel-down. This motion can allow greater speed and higher note density at louder volumes but is not efficient for slow tempos or sparse rhythms.[15]

Drummers such as Thomas Lang, Virgil Donati, and Terry Bozzio are capable of performing complicated solos on top of an ostinato bass drum pattern. Thomas Lang, for example, has mastered the heel-up and heel-down (single- and double-stroke) to the extent that he is able to play dynamically with the bass drum and to perform various rudiments with his feet.

In order to play "doubles" on the pedal, drummers can employ 3 main techniques: slide, swivel, or heel-toe. In the slide technique, the pedal is struck around the middle area with the ball of the foot. As the drum produces a sound, the toe is slid up the pedal. After the first stroke, the pedal will naturally bounce back, hit the toe as it slides upwards, and rebound for a second strike. In the swiveling double, the pedal is struck once in the normal manner for the first note, then the heel is immediately rotated around the ball of the foot to the side of the pedal while simultaneously playing a second stroke. This rotation can be to the inside or outside, either will work, and results in a faster second stroke than is ordinarily possible.[15] In the heel-toe technique the foot is suspended above the foot-board of the pedal. The entire foot is brought down and the ball of the foot strikes the pedal. The foot snaps up, the heel comes off the footboard, and the toes come down for a second stroke. Once mastered either technique allows the player to play very fast double strokes on the bass drum. Noted players include Rod Morgenstein, Tim Waterson (who formerly held the world record for the fastest playing on a bass drum, using double bass), Tomas Haake, Chris Adler, Derek Roddy, Danny Carey and Hellhammer. The technique is commonly used in death metal and other extreme forms of music where triggers and double bass are typically employed. Double strokes can only properly replace single strokes for long runs of evenly spaced notes when using triggers or sample replacement as the sound is inherently uneven. Some tempos are only possible with double strokes, however.

Double bass drum

In many forms of heavy metal and hard rock, as well as some forms of jazz, fusion, and punk, two bass drums are used, or alternatively two pedals on one bass drum. If two drums are used, that is often to give a more impressive appearance on large stages, but sometimes, the second drum is pitched differently to provide some variety in the notes, thus creating a more nuanced sound. The first person to use and popularize the double bass drum setup was jazz drummer Louie Bellson,[17] who came up with the idea when he was still in high school. Ray McKinley was, by 1941, using this setup as well.[18] Double bass drums were popularized in the 1960s by rock drummers Ringo Starr of The Beatles, Ginger Baker of Cream, Mitch Mitchell of the Jimi Hendrix Experience, Keith Moon of the Who and Nick Mason of Pink Floyd. After 1970, Billy Cobham and Narada Michael Walden used double kick drum with the jazz fusion project Mahavishnu Orchestra, Chester Thompson with Frank Zappa and Weather Report, Barriemore Barlow with Jethro Tull, and Terry Bozzio with Frank Zappa. For these genres the focus was 'odd-meter grooves and mind blowing solos'.[19] Double bass drumming later became an integral part of heavy metal,[19] as pioneered by the likes of Les Binks, Carmine Appice, Ian Paice, Cozy Powell, Phil Taylor and Tommy Aldridge. American thrash metal band Slayer's former drummer Dave Lombardo was named "the godfather of double bass" by the magazine Drummerworld. Later metal genres including death metal use double kick drumming extensively often with blast beat techniques, whilst focusing on precision, 'endurance', 'speed' and 'rapid footwork'.[19]

Double bass drumming can be achieved with a number of techniques; most commonly, with simple alternating single strokes. However, in order to increase the speed, some drummers use the heel-toe technique; these are essentially double strokes where the drummer can perform two hits with one foot movement, which causes less fatigue at higher tempos.

Notable names that have a hand in raising the bar for double bass drumming, include: Terry Bozzio, Simon Philips, Virgil Donati, Derek Roddy, Gene Hoglan, George Kollias, Bobby Jarzombek and Tomas Haake. Bozzio introduced the ostinato in his "Melodic Drumming and the Ostinato" educational DVDs, playing various drum rudiments on the feet, while freely playing with the hands, creating polyrhythms.[20] Donati is regarded as the first drummer to successfully use inverted double strokes with both feet, in addition to complex, syncopated ostinato patterns.[21] Roddy, Hoglan and Kollias are acknowledged as the leaders of extreme metal drumming with their use of single strokes at 250+ beats per minute, while, Jarzombek and Haake's double bass drumming influenced the djent genre.

The history and development of double bass (as well as notated playing instruction) can be traced in the books Encyclopedia of Double Bass Drumming written by Bobby Rondinelli and Michael Lauren[22] and The Complete Double Bass Drumming Explained written by Ryan Alexander Bloom.[23] In addition to these books, Double Bass Drumming written by Joe Franco and Double Bass Drum Freedom written by Virgil Donati are also commonly used resources for double bass instruction.

In marching bands

The "bass line" is a unique musical ensemble consisting of graduated pitch marching bass drums commonly found in marching bands and drum and bugle corps. Each drum plays a different note, and this gives the bass line a unique task in a musical ensemble. Skilled lines execute complex linear passages split among the drums to add an additional melodic element to the percussion section. This is characteristic of the marching bass drum—its purpose is to convey complex rhythmic and melodic content, not just to keep the beat. The line provides impact, melody, and tempo due to the nature of the sound of the instruments. The bass line usually has from as many as seven bass drums to as few as two. But most high school drumlines consist of between three and five.

Components

A bass line typically consists of four or five musicians, each carrying one tuned bass drum, although variations do occur. Smaller lines are not uncommon in smaller groups, such as some high school marching bands, and several groups have had one musician playing more than one bass drum, usually small ones, with one mounted on top of the other.

The drums are typically between 16" and 32" in diameter, but some groups have used bass drums as small as 14" and larger than 36". The drums in a bass line are tuned such that the largest will always play the lowest note with the pitch increasing as the size of the drum decreases. Individually, the drums are usually tuned higher than other bass drums (drum set kick drums or orchestral bass drums) of the same size, so that complex rhythmic passages can be heard clearly and articulated.

Unlike the other drums in a drumline, the bass drums are generally mounted sideways, with the drumhead facing horizontally, rather than vertically. This results in several things. First of all, to ensure that a vibrating membrane is facing the audience, bass drummers must face perpendicular to the rest of the band and so are the only section in most groups whose bodies do not face the audience while playing. Consequently, bass drummers usually point their drums at the back of the bass drummer in front of them, so that the drum heads will all be lined up, from the audience's point of view, next to one another in order to produce optimal sound output.

Playing

Since the bass drum is oriented differently from a snare or tenor drum, the stroke itself is different, but the fundamentals remain the same. The player's forearms should be parallel to the ground and bent at the elbows. The line between their shoulder and elbow should be vertical and the mallet should be held upward at a 45-degree angle.[24] The hands hold bass mallets in such a way as to place the center of the mallet in the center of the head. The mallet shaft bottom should be flush against the bottom part of the hand when playing, differing from other grips typical to percussion instruments.

The motion of the basic stroke is either similar to the motion of turning a doorknob, that is, an absolute forearm rotation, or similar to that of a snare drummer, where the wrist is the primary actor, or more commonly, a hybrid of these two strokes. Bass drum technique sees huge variation between different groups both in the ratio of forearm rotation to wrist turn and the differing views on how the hand works while playing. Some techniques also call for the use of fingers supporting the motion of the mallet by opening or closing, but no matter whether it is open or closed the thumb needs to be close to the rest of the fingers.

However, the basic stroke on a drum produces just one of the many sounds a bass line can produce. Along with the solo drum, the "unison" is one of the most common sounds used. It is produced when all of the bass drums play a note at the same time and with a balanced sound; this option has a very full, powerful sound. The rim click, which is when the shaft (near the mallet head) is struck against the rim of the drum, either solo or in unison. Rimshots are rare on a bass drum and usually only happen on the top drums.[25]

The different positions of the typical five person bass line each require different skills, though not necessarily different levels of skills. Contrary to the popular belief that "higher is better," each drum has its own critical role to play. Bottom, or fifth bass, is the largest, heaviest, and lowest drum in the drumline. Consequently, it is used frequently to help maintain pulse in an ensemble and is thus sometimes referred to as the "heartbeat" of the group (the bottom bass was also often referred to as the "thud" bass in days gone by, indicating that many of their notes were the last one at the end of a phrase). Although this player does not always play as many notes as fast as other bass drummers (the depth of pitch renders most complex passages indistinguishable from a roll), his or her role is essential not only to the sound of the bass line or the drum line, but to the ensemble as a whole, especially in the case of parade bands.

The fourth bass is slightly smaller than the bottom drum (generally two to four inches (51 to 102 mm) smaller in diameter) and can function tonally similar to its lower counterpart, but usually plays slightly more rapid parts and is much more likely to play "off the beat" - in the middle rather than at the beginning or end of a passage. The third bass is the middle drum, both in terms of position and tone. Its function is usually that of the archetypical bass drum. This player plays an integral role in the actual rendering of complex linear passages. The second bass is known for having a job in the drumline. This player's parts are very likely to be directly adjacent to the beginning or end of a phrase and less likely to be on a beat, which is highly counter-intuitive, especially to a new player. Sometimes this drum can function about the same as the top drum, but usually the second and top drummer function as a unit, playing rudimentarily difficult passages split between them.

Top, or first, bass is the highest pitched drum in the bass line and usually starts or ends phrases. The high tension drum heads allow this player to play notes that are just as taxing as those of the snare line, and often the top bass will play a part in unison with the snare line to add some depth to their sound. Some bass lines have more than five bass drums, with the largest being the largest number (bass 7 on a 7 bass line), and the smallest being referred to as first bass.

Marching

In a marching band's field show, bass drummers typically face either goal line. It can be difficult to see the drum major and other players on the field when facing away from the center. For this reason, the players may turn to face the opposite direction during a show. Turns are typically done in unison or rippled for a different effect.

With large bass drums, more strength and control is required to turn quickly. Achieving a clean turn requires the player to use large core muscles to stop momentum of the drum at the correct time and direction.

In some marching bands, the bass drum is used to give orders to the band. For example,

- One stroke is used to order the band (and associated troops) to start/stop marching

- Two strokes are used to order the band to stop marching

- Two strong strokes (Double Beat) are used when the music is due to cut off (usually a double beat then three beats and finish)

References

- ^ Snoman, Rick (2004). The Dance Music Manual: Tools, Toys and Techniques. ISBN 0-240-51915-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Del Mar, Norman (1981). Anatomy of the Orchestra. ISBN 0-571-11552-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Blades, James (2005). Percussion Instruments and Their History. Faber and Faber LTD: London. ISBN 9780933224612.

- ^ a b Ozeke, Sezen, "Musical Instruments of India and Turkey." Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi XX, 2007.

- ^ a b c d "Virtual Instruments, Sample Library, Audio Software, Virtual Orchestra, Vienna Symphonic Library, VSL, Vienna Instruments, vienna symphonic, vienna strings, orchestral vst, synchron series, Orchestersound, Streichersound, audio plugin - Vienna Symphonic Library". www.vsl.co.at.

- ^ a b Zoltan, Falvy, "Middle-East European Court Music." Studia Musicologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae, (1987).

- ^ a b McGowan, Keith, "The Prince and the Piper: Haut, Bas and the Whole Body in Early Modern Europe. Early Music, Vol. 27, No. 2, Instruments and Instrumental Music (May 1999), pp. 211-216.

- ^ a b Sardar, Marika. "The Greater Ottoman Empire, 1600–1800". In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000.

- ^ a b c Lundstrom, Hakan and Tavan, Damrong, "Kammu Gongs and Drums (II): The Long Wooden Drum and Other Drums." Asian Folklore Studies, Vol. 40, No. 2 (1981), pp. 173-189.

- ^ a b Nichols, Geoff (1997). The Drum Book: The History of the Rock Drum Kit. ISBN 9781476854366.

- ^ Protection Racket bass drum muffler Archived June 20, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, for example.

- ^ Nichols (1997), p. 8-12.

- ^ "Hardware Archived November 6, 2007, at the Wayback Machine", PearlDrum.com. Accessed 2004.

- ^ Marshall, Paul and Radcliff, Mike (1999). "Glossary of Terms (Drum kit/Drumset)", DrumDojo.com.

- ^ a b Bloom, Ryan Alexander. The Complete Double Bass Drumming Explained. NY: Hudson Music, 2017.

- ^ Franco, Joe (1984). Double Bass Drumming, p.3. Alfred Music. ISBN 9781457458828.

Weckl, Dave (2004). Exercises for Natural Playing, p.16. Carl Fischer. ISBN 9780825850981. Features quarter note ride rather than eighth, as does Mattingly (2006).

Berengena, Alfred (2005). Essential Double Bass Drumming, p.53. DINSIC. ISBN 9788495055996. Features RRLL or LLRR rather than RLRL or LRLR. - ^ Mattingly, Rick (2006). All About Drums: A Fun and Simple Guide to Playing Drums, unpaginated. Hal Leonard. ISBN 9781476865867.

- ^ "Ray McKinley Plus Slingerland 'Radio Kings' Equals Solid Rhythm" (advertisement). Metronome 57:8 (August 1941), 31.

- ^ a b c Nyman, John (2009-05-10). "Double Bass Drum: A Short History". DRUM!. Archived from the original on 2016-10-19. Retrieved 2012-01-29.

- ^ "Terry Bozzio: Melodic Drumming and the Ostinato, Vols. 1, 2, 3 - DrumChannel.com - The Best Drum Lessons and Drum Shows Online". 18 November 2016. Archived from the original on 2016-11-18.

- ^ "Modern Drummer" (PDF). 10 January 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-01-10.

- ^ Rondinelli, Bobby and Lauren, Miachel. Encyclopedia of Double Bass Drumming. New Jersey: Modern Drummer, 2000.

- ^ Bloom, Ryan Alexander. The Complete Double Bass Drumming Explained. New York: Hudson Music, 2017.

- ^ Rael, Eliso. "Bass Drum Technique (Marching)". Archived from the original on 2012-11-14. Retrieved 2023-02-14.

- ^ Powelson, Bill. "Drum Lesson Menu #2: Drums - Types of Rimshots". studydrums.com. Retrieved 2023-02-14.

External links

![]() Media related to Bass drums at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Bass drums at Wikimedia Commons

- Bass Drum Pedal Techniques - lesson on Kick pedal set-up and basic playing techniques

- How To Record The Perfect Kick Drum Sound Archived 2007-10-24 at the Wayback Machine - Tips on recording a bass drum

- Double Bass Legends: A Short History

- Effective Bass Drum Techniques

- How to tune a bass drum