Operation Rheinübung

| Operation Rheinübung | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Battle of the Atlantic | |

| Type | Commerce Raid |

| Location | The Atlantic Ocean |

| Date | 18–27 May 1941 |

| Executed by | Battleship Bismarck Heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen |

| Outcome | Opertional failure

|

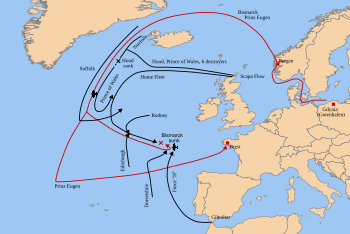

Operation Rheinübung (German: Unternehmen Rheinübung) was the last sortie into the Atlantic by the new German battleship Bismarck and heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen on 18–27 May 1941, during World War II. This operation aimed to block Allied shipping to the United Kingdom as the previously successful Operation Berlin had done. After Bismarck had sunk HMS Hood during the Battle of the Denmark Strait (24 May), it culminated with the sinking of the Bismarck (27 May), while Prinz Eugen escaped to port in occupied France. From that point on, Germans would rely only on U-boats to wage the Battle of the Atlantic.

Background

During both World Wars, Britain relied heavily on merchant ships to import food, fuel, and raw materials, such things were crucial both for civilian survival and the military effort. Protecting this lifeline was a high priority for British forces, as its disruption would significantly weaken the British economy and its military capabilities, and Britain might be forced to negotiate peace, seek an armistice, or reduce its capacity to resist if this supply line could be severed. Such an outcome would shift the balance of power in Europe decisively, potentially giving Germany control over Western Europe without a nearby base of opposition.

Germany's naval leadership (under Admiral Erich Johann Albert Raeder) at the time firmly believed that defeat by blockade was achievable. However, they also believed that the primary method to achieve this objective was to use traditional commerce raiding tactics, founded upon surface combatants (cruisers, battle-cruisers, fast battleships) that were only supported by submarines. Regardless of the method or manner, Raeder convinced the High Command (OKW) and Hitler that if this lifeline were severed, Britain would be defeated, regardless of any other factors.

Operation Rheinübung was the latest in a series of raids on Allied shipping carried out by surface units of the Kriegsmarine. It was preceded by Operation Berlin, a highly successful sortie by Scharnhorst and Gneisenau which ended in March 1941.

By May 1941, the Kriegsmarine battleships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau were at Brest, on the western coast of France, posing a serious threat to the Atlantic convoys, and were heavily bombed by the Royal Air Force. The original plan was to have both ships involved in the operation, but Scharnhorst was undergoing major repairs to her engines, and Gneisenau had just suffered a damaging torpedo hit days before, which put her out of action for 6 months. This left just two new warships available to the Germans: the battleship Bismarck and the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen (while the Kriegsmarine had three serviceable light cruisers, none had the endurance necessary for a long Atlantic operation), both initially stationed in the Baltic Sea.

The aim of the operation was for Bismarck and Prinz Eugen to break into the Atlantic and attack Allied shipping. Grand Admiral Erich Raeder's orders to Admiral Günther Lütjens were that "the objective of the Bismarck is not to defeat enemies of equal strength, but to tie them down in a delaying action, while preserving her combat capacity as much as possible, so as to allow Prinz Eugen to get at the merchant ships in the convoy" and "The primary target in this operation is the enemy's merchant shipping; enemy warships will be engaged only when that objective makes it necessary and it can be done without excessive risk".[1]

To support and provide facilities for the capital ships to refuel and rearm, German Naval Command (OKM) established a network of tankers and supply ships in the Rheinübung operational area. Seven tankers and two supply ships were sent as far afield as Labrador in the west and the Cape Verde Islands in the south.

Lütjens had requested that Raeder delay Rheinübung long enough either for Scharnhorst to complete repairs to her engines and be made combat-worthy, allowing her to rendezvous at sea with Bismarck and Prinz Eugen; or for Bismarck's sister ship Tirpitz to accompany them. Raeder had refused, as Scharnhorst would not be made ready to sail until early July. The crew of the newly completed Tirpitz was not yet fully trained, and over Lütjens's protests, Raeder ordered Rheinübung to go ahead. Raeder's principal reason for going ahead was his knowledge of the upcoming Operation Barbarossa, where the Kriegsmarine was going to play only a small, supporting role. Raeder's desire was to score a major success with a battleship before Barbarossa, an act that might impress upon Hitler the need not to cut the budget for capital ships.[2]

To meet the threat from German surface ships, the British had stationed at Scapa Flow the new battleships King George V and Prince of Wales as well as the battlecruiser Hood and the newly commissioned aircraft carrier Victorious. Elsewhere, Force H at Gibraltar could muster the battlecruiser Renown and the aircraft carrier Ark Royal; at sea in the Atlantic on various duties were the older battleships Revenge and Ramillies, the 16 inch gun-armed Rodney and the older battlecruiser Repulse. Cruisers and air patrols provided the fleet's "eyes". At sea, or due to sail shortly, were 11 convoys, including a troop convoy.

OKM did not take into account the Royal Navy's determination to destroy the German surface fleet. To ensure that Bismarck was sunk, the Royal Navy would ruthlessly strip other theatres of vessels. This would include denuding valuable convoys of their escorts. The British would ultimately deploy six battleships, three battlecruisers, two aircraft carriers, 16 cruisers, 33 destroyers and eight submarines, along with patrol aircraft. It would become the largest naval force assigned to a single operation up to that point in the war.[3]

Rheinübung

Bismarck sails

The heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen sailed at about 21:00 on 18 May 1941 from Gotenhafen (Gdynia, Poland), followed at 2:00 a.m., 19 May, by Bismarck. Both ships proceeded under escort, separately and rendezvoused off Cape Arkona on Rügen Island in the western Baltic,[4] where the destroyers Z23 and Z16 Friedrich Eckoldt joined them.[5] They then proceeded through the Danish Islands into the Kattegat. Entering the Kattegat on 20 May Bismarck and Prinz Eugen sailed north toward the Skagerrak, the strait between Jutland and Southern Norway, where they were sighted by the Swedish aircraft-carrying cruiser Gotland on around 1:00 p.m. Gotland forwarded the sighting in a routine report. Earlier, around noon, a flight of Swedish aircraft also detected the German vessels and likewise reported their sighting.[6]

On 21 May the Admiralty was alerted by sources in the Swedish government that two large German warships had been seen in the Kattegat. The ships entered the North Sea and took a brief refuge in Grimstadfjord near Bergen, Norway on 21 May where Prinz Eugen was topped off with fuel, making a break for the Atlantic shipping lanes on 22 May.[7] By this time, Hood and Prince of Wales, with escorting destroyers, were en route to the Denmark Strait, where two cruisers, Norfolk and Suffolk were already patrolling. The cruisers Manchester and Birmingham had been sent to guard the waters south-east of Iceland.

Once the departure of the German ships was discovered, Admiral Sir John Tovey, the Commander-in-Chief of the British Home Fleet, sailed with King George V, Victorious and their escorts to support those already at sea. Repulse joined soon afterwards.

On the evening of 23 May, Suffolk sighted Bismarck and Prinz Eugen in the Denmark Strait, close to the Greenland coast. Suffolk immediately sought cover in a fog bank and alerted The Admiralty. Bismarck opened fire on Norfolk at a range of six miles but Norfolk escaped into fog. Norfolk and Suffolk, outgunned, shadowed the German ships using radar. No hits were scored but the concussion of the main guns firing at Norfolk had knocked out Bismarck's radar causing Lütjens to re-position Prinz Eugen ahead of Bismarck. After the German ships were sighted, British naval groups were redirected to either intercept Lütjens' force or to cover a troop convoy.

Battle of the Denmark Strait

Hood and Prince of Wales made contact with the German force early on the morning of 24 May, and the action started at 5:52 a.m., with the combatants about 25,000 yards (23,000 m) apart. Gunners onboard Hood initially mistook Prinz Eugen that was now in the lead for Bismarck and opened fire on her; Captain Leach commanding HMS Prince of Wales realised Vice-Admiral Holland's error and engaged Bismarck from the outset. Both German ships were firing at Hood. Hood suffered an early hit from Prinz Eugen which started a rapidly spreading fire amidships.

Then, at about 6 a.m., one or more of Hood's magazines exploded, probably as the result of a direct hit by a 38 cm (15 in) shell from Bismarck. The massive explosion broke the great battlecruiser's back, and she sank within minutes.[8] All but three of her 1,418-man crew died, including Vice Admiral Lancelot Holland, commanding officer of the squadron.

Prince of Wales continued the action, but suffered multiple hits with 38 cm (15 in) and 20.3 cm (8 in) shells, and experienced repeated mechanical failures with her main armament. Her commanding officer, Captain Leach, was wounded when one of Bismarck's shells struck Prince of Wales' bridge. Leach broke off the action, and the British battleship retreated under cover of a smokescreen.

Bismarck had been hit three times but Admiral Lütjens overruled Bismarck's Captain Ernst Lindemann who wanted to pursue the damaged Prince of Wales and finish her off. All of the hits on Bismarck had been inflicted by Prince of Wales' 14-inch (356 mm) guns. One of the hits had penetrated the German battleship's hull near the bow, rupturing some of her fuel tanks, causing her to leak oil continuously and at a serious rate. This was to be a critical factor as the pursuit continued, forcing Bismarck to make for Brest instead of escaping into the great expanse of the Atlantic. The resulting oil slick also helped the British cruisers to shadow her.

The pursuit

Norfolk and Suffolk and the damaged Prince of Wales continued to shadow the Germans, reporting their position to draw British forces to the scene. In response, it was decided that the undamaged Prinz Eugen would detach to continue raiding, while Bismarck drew off the pursuit. In conjunction with this, Admiral Dönitz committed the U-boat arm to support Bismarck with all available U-boats in the Atlantic.[9] He organised two patrol lines to trap the Home Fleet should Bismarck lead her pursuers to them. One line of 7 boats was arrayed in mid-Atlantic while another, of 8 boats, was stationed west of the Bay of Biscay. At 6:40 p.m. on 24 May, Bismarck turned on her pursuers and briefly opened fire to cover the escape of Prinz Eugen. The German cruiser slipped away undamaged.[7]

At 10 p.m., Victorious was 120 miles (190 km) away and launched an air attack with nine Fairey Swordfish torpedo bombers, which were guided in by Norfolk. In poor weather, and against heavy fire, they attacked and made a single torpedo hit under the bridge. However, up against strong belt armour and anti-torpedo bulges, it failed to cause substantial damage. The attacking aircraft were all safely recovered by Victorious, despite poor weather, darkness, aircrew inexperience and the failure of the carrier's homing beacon.[7]

At 3 a.m. on 25 May, the British shadowers lost contact with Bismarck. At first, it was thought that she would return to the North Sea, and ships were directed accordingly. Then Lütjens, believing that he was still being shadowed by the British, broke radio silence by sending a long radio message to headquarters in Germany. This allowed the British to triangulate Bismarck's approximate position and send aircraft to hunt for the German battleship. By the time that it was realised that Lütjens was heading for Brest, Bismarck had broken the naval cordon and gained a lead. By 11 p.m., Lütjens was well to the east of Tovey's force and had managed to evade Rodney. Bismarck was short of fuel due to the damaging hit inflicted by Prince of Wales which had caused Lütjens to reduce speed to conserve fuel but Bismarck still had enough speed to outrun the heavy units of the Home Fleet and reach the safety of France. From the south, however, Somerville's Force H with the carrier Ark Royal, the battlecruiser Renown, and the light cruiser HMS Sheffield were approaching to intercept.

The British ships were also beginning to run low on fuel, and the escape of Bismarck seemed more and more certain. However, at 10:30 a.m. on 26 May, a PBY Catalina flying-boat, based at Lough Erne, Northern Ireland, found Bismarck. She was 700 miles (1,100 km) from Brest and not within range of Luftwaffe air cover.

This contact was taken over by two Swordfish from Ark Royal. This carrier now launched an airstrike, but her aircrew were unaware of Sheffield's proximity to Bismarck, mistook the British cruiser for the German battleship and therefore immediately attacked her. Their torpedoes had been fitted with influence detonators, and several of them exploded prematurely. Others missed their target, and the attacking aircraft then received a warning from Ark Royal that Sheffield was in the vicinity, whereupon the Swordfish finally recognised the cruiser and broke off the attack.

Ark Royal now launched, in almost impossibly bad weather conditions for air operations, and from a distance of less than 40 miles upwind of Bismarck, a second strike consisting of 15 Swordfish. These were carrying torpedoes equipped with the standard and reliable contact detonators. The attack resulted in two or three hits on the German ship, one of which inflicted critical damage on her steering. A jammed rudder now meant she could now only sail away from her intended destination of Brest. At midnight, Lütjens signalled his headquarters: "Ship unmanoeuvrable. We shall fight to the last shell. Long live the Führer."[10]

Bismarck's end

The battleships Rodney and King George V waited for daylight on 27 May before attacking. At 8:47 a.m., they opened fire, quickly hitting Bismarck. Her gunners achieved near misses on Rodney, but the British ships had silenced Bismarck's main guns within half an hour. Despite close-range shelling by Rodney, a list to port, and widespread fires, Bismarck did not sink.

According to David Mearns and James Cameron's underwater surveys in recent years the British main guns achieved only four hits on Bismarck's main armoured belt, two through the upper armour belt on the starboard side from King George V and two on the port side from Rodney. These four hits occurred at about 10:00 a.m., at close range, causing heavy casualties among the sheltering crew.

Nearly out of fuel – and mindful of possible U-boat attacks – the British battleships left for home. The heavy cruiser Dorsetshire attacked with torpedoes and made three hits. Scuttling charges were soon set off by German sailors, and at 10:40 a.m., Bismarck capsized and sank. Dorsetshire and the destroyer Maori rescued 110 survivors. After an hour, rescue work was abruptly ended when there were reports of a U-boat presence. Another three survivors were picked up by U-74 and two by the German weather ship Sachsenwald. Over 2,000 died, including Captain Lindemann and Admiral Lütjens.

Aftermath

After separating from Bismarck, Prinz Eugen went further south into the Atlantic, intending to continue the commerce raiding mission. On 26 May, with just 160 tons of fuel left, she rendezvoused with the tanker Spichern and refuelled. On 27 May, she developed engine trouble, which worsened over the next few days. On 28 May, she received a further refueling from Esso Hamburg. With her speed reduced to 28 knots (52 km/h; 32 mph), it was no longer considered practicable to continue. She abandoned her commerce raiding mission without sinking any merchant ships, and made her way to Brest, arriving on 1 June where she remained under repair until the end of 1941. She later escaped from France with two other German battleships during the Channel Dash.

In the action, just two U-boats had sighted the British forces, and neither was able to attack. In the aftermath, the British ships were able to evade the patrol lines as they returned to base; there were no further U-boat contacts. The Luftwaffe also organized sorties against the Home Fleet, but none were successful until 28 May, when planes from Kampfgeschwader 77 attacked and sank the destroyer Mashona.

After Rheinübung, a recent breakthrough into the Kriegsmarine's enigma network enabled the Royal Navy to mount a concerted effort to round up the network of supply ships deployed to refuel and rearm the Rheinübung ships. The first success came on 3 June, when the tanker Belchen was discovered by the cruisers Aurora and Kenya south of Greenland. On 4 June the tanker Gedania was found in mid-Atlantic by Marsdale, while 100 miles (160 km) east the supply ship Gonzenheim was caught by the armed merchant cruiser Esperance Bay, and aircraft from Victorious. On the same day in the south Atlantic, midway between Belém and Freetown, the southernmost limit of the Rheinübung operation, the tanker Esso Hamburg was intercepted by the cruiser London; while the following day London, accompanied by Brilliant, sank the tanker Egerland. A week later, on 12 June, the tanker Friederich Breme was sunk by the cruiser HMS Sheffield in the mid-Atlantic. On 15 June, the tanker Lothringen was sunk by the cruiser Dunedin, with aircraft from Eagle. In just over two weeks, 7 of the 9 supply ships assigned to Operation Rheinübung had been accounted for, with serious consequences for future German surface operations.

Conclusion

Operation Rheinübung was a failure, and although the Germans scored a success by sinking "The Mighty Hood", this was offset with the loss of the modern battleship Bismarck, which represented one-quarter of the Kriegsmarine's capital ships.[11] No merchant ships were sunk or even sighted by the German heavy surface units during the 2-week raid. Allied convoys were not seriously disrupted; most convoys sailed according to schedule, and there was no diminution of supplies to Britain. On the other hand, the Atlantic U-boat campaign was disrupted; boats in the Atlantic sank just 2 ships in the last weeks of May, compared to 29 at the beginning of the month.[12] As a result of Bismarck's sinking, Hitler forbade any further Atlantic sorties,[13] and her sister ship Tirpitz was sent to Norway. The Kriegsmarine was never again able to mount a major surface operation against Allied supply routes in the North Atlantic; henceforth its only weapon was the U-boat campaign.

References

- ^ Boyne, 53-54.

- ^ Murray, Williamson & Millet, Alan War To Be Won, Harvard: Belknap Press, 2000 page 242.

- ^ Boyne, 54.

- ^ Ballard, 60.

- ^ Garzke et al., p. 163

- ^ Garzke et al., p. 165

- ^ a b c "Operation Rheinbung".

- ^ "H.M.S. Hood Association-Battle Cruiser Hood - the History of H.M.S. Hood: Part 2 of the Pursuit of Bismarck and Sinking of Hood (Battle of the Denmark Strait)".

- ^ Blair p288

- ^ "Bismarck - the History - the Fatal Torpedo Hit". Archived from the original on 25 October 2008. Retrieved 8 October 2008.

- ^ Blair p292

- ^ Blair p293

- ^ Bercuson, David J; Herwig, Holger H (2003). Bismarck. London: Pimlico/Random House. p. 306. ISBN 0-09-179516-8. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

Bibliography

- Garzke, William H. (2019). Battleship Bismarck: A Design and Operational History. Dulin, Robert O.,, Jurens, William,, Cameron, James. Annapolis, Maryland. ISBN 978-1-59114-569-1. OCLC 1055269312.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Further reading

- Robert D. Ballard: The Discovery of the Bismarck (1990). ISBN 0-670-83587-0.

- Blair, Clay (2000). Hitler's U-Boat War: The Hunters 1939-1942. Cassell. ISBN 0-304-35260-8.

- Walter Boyne, Clash of Titans: World War II at Sea (New York: Simon & Schuster 1995).

- Fritz Otto Busch :The Story of Prinz Eugen (1958). ISBN (none).

- Sir Winston Churchill: The Second World War.

- Ludovic Kennedy: Pursuit – the Sinking of the Bismarck (1974).

- Stephen Roskill: The War at Sea 1939-1945 Vol I (1954) ISBN (none).

External links

- Rico, José. "Operation Rheinübung". kBismarck.com. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- Asmussen, John. "Bismarck". Bismarck-class.dk. Archived from the original on 15 July 2019. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- Asmussen, John. "Prinz Eugen". Admiral-Hipper-Class.dk. Retrieved 21 January 2016.