Oneirodidae

| Dreamers | |

|---|---|

| |

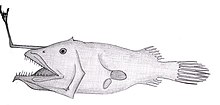

| Oneirodes macrosteus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Lophiiformes |

| Suborder: | Ceratioidei |

| Family: | Oneirodidae T. N. Gill, 1879 |

| Genera | |

|

see text | |

Oneirodidae, the dreamers are a family of marine ray-finned fishes belonging to the order Lophiiformes, the anglerfishes. These fishes are deepwater fishes found in the Atlantic, Indian and Pacific Oceans, and it is the most diverse family of fishes in the bathypelagic zone.

Taxonomy

Oneirodidae was first proposed as a family in 1879 by the American biologist Theodore Gill[1] with Oneirodes as its only genus.[2] Oneirodes had been proposed as a monospecific genus in 1871 by the Danish zoologist Christian Frederik Lütken when he described O. eschrichtii, giving its type locality as off the western coast of Greenland.[3] The 5th edition of Fishes of the World classifies this family in the suborder Ceratioidei of the anglerfish order Lophiiformes.[4]

Genera

Oneirodidae has the following genera classified within it:[5][6]

- Bertella Pietsch, 1973

- Chaenophryne Regan, 1925

- Chirophryne Regan & Trewavas, 1932

- Ctenochirichthys Regan & Trewavas, 1932

- Danaphryne Bertelsen, 1951

- Dermatias H. M .Smith & Radcliffe, 1912

- Dolopichthys Garman, 1899

- Leptacanthichthys Regan & Trewavas, 1932

- Lophodolos Lloyd, 1909

- Microlophichthys Regan & Trewavas, 1932

- Oneirodes Lütken, 1871

- Pentherichthys Regan & Trewavas, 1932

- Puck Pietsch, 1978

- Spiniphryne Bertelsen, 1951

- Tyrannophryne Regan & Trewavas, 1932

With over 60 species classified within this family, it is the most species diverse family of fishes in the bathypelagic zone.[7]

Etymology

Oneirodidae is derived from Oneirodes, its type genus, which means "dream-like". Lütken did not explain this choice of name, David Starr Jordan and Barton Warren Evermann suggested in 1898 that the name referred to the small, skin-covered eyes. Alternatively, in 2009 Theodore Wells Pietsch III proposed that the name was given because a "fish so strange and marvelous that it could only be imagined in the dark of the night during a state of unconsciousness".[8]

Characteristics

Oneirodidae are, like other anglerfishes, sexually dimorphic. The metamorphosed females are very variable in body shape and most have short, deep globe-like or slightly compressed bodies although some taxa have elongate, streamlined bodies.[9] These fishes typically have naked skin, although some taxa have short dermal spines. They have between 4 and 8 soft rays in the dorsal fin and between 4 and 7 soft rays in the anal fin. They also have forwardly directed, thin, flattened process that reaches over the sphenotic, a bone in the posterior part of the orbit. The jaws are of similar length with neither protruding beyond the other.[4] These fishes also have a bioluminescent bulb at the tip on the illicium, lack any fleshy growths along the centre of the back, do not have upward pointing mouths, there are teeth on the upper denticular bone,, the esca has no small tooth-like structures, they have large eyes and large olfactory organs with forward opening nostrils located at the end of the snout. The males, like those of other ceratioids, are considerably smaller than the metamorphosed females, do not have an esca or an illicium extending beyond the dermis, their eyes and olfactory organs are much larger than those of the females and they have pincer-like jaws armed with hooked denticular teeth, thought to be utilised in grabbing on to the female. They also have naked skin and the front end of the pterygophore is distant from the rear end of the denticular bone.[10] The males in this family are typically not sexual parasites of the females.[4] The largest females are up to 37 cm (15 in) in length contrasting with the longest males being 2.85 cm (1.12 in) in length.[9]

Distribution and habitat

Oneirodidae are found in all the world's oceans in the mesopelagic and bathypelagic zones at depths between 300 and 3,000 m (980 and 9,840 ft).[9]

Biology

Fish of this family are predatory, feeding on other fish and on crustaceans. They are oviparous with pelagic eggs and larvae.[9]

References

- ^ Richard van der Laan; William N. Eschmeyer & Ronald Fricke (2014). "Family-group names of recent fishes". Zootaxa. 3882 (2): 1–230. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3882.1.1. PMID 25543675.

- ^ Gill, Theodore (1878). "Synopsis of the pediculate fishes of the eastern coast of extratropical North America". Proceedings of the United States National Museum. 1 (30): 215–221. doi:10.5479/si.00963801.1-30.215.

- ^ Eschmeyer, William N.; Fricke, Ron & van der Laan, Richard (eds.). "Species in the genus Oneirodes". Catalog of Fishes. California Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 3 July 2024.

- ^ a b c Nelson, J.S.; Grande, T.C.; Wilson, M.V.H. (2016). Fishes of the World (5th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 508–518. doi:10.1002/9781119174844. ISBN 978-1-118-34233-6. LCCN 2015037522. OCLC 951899884. OL 25909650M.

- ^ Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.). "Family Oneirodidae". FishBase. February 2024 version.

- ^ Eschmeyer, William N.; Fricke, Ron & van der Laan, Richard (eds.). "Genera in the family Oneirodidae". Catalog of Fishes. California Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 3 July 2024.

- ^ Nelson, J.S.; Grande, T.C.; Wilson, M.V.H. (2016). Fishes of the World (5th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 312–313. doi:10.1002/9781119174844. ISBN 978-1-118-34233-6. LCCN 2015037522. OCLC 951899884. OL 25909650M.

- ^ Christopher Scharpf (3 June 2024). "Order LOPHIIFORMES (part 2): Families CAULOPHRYNIDAE, NEOCERATIIDAE, MELANOCETIDAE, HIMANTOLOPHIDAE, DICERATIIDAE, ONEIRODIDAE, THAUMATICHTHYIDAE, CENTROPHRYNIDAE, CERATIIDAE, GIGANTACTINIDAE and LINOPHRYNIDAE". The ETYFish Project Fish Name Etymology Database. Christopher Scharpf. Retrieved 3 July 2024.

- ^ a b c d Dianne J. Bray. "Dreamers, ONEIRODIDAE". Fishes of Australia. Museums Victoria. Retrieved 4 July 2024.

- ^ E. Bertelsen and Theodore W. Pietsch (1983). "The Ceratioid Anglerfishes of Australia" (PDF). Records of the Australian Museum. 35 (2): 77–93. doi:10.3853/j.0067-1975.35.1983.303.