Ullucus

| Ullucus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Order: | Caryophyllales |

| Family: | Basellaceae |

| Genus: | Ullucus Caldas |

| Species: | U. tuberosus |

| Binomial name | |

| Ullucus tuberosus Caldas | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

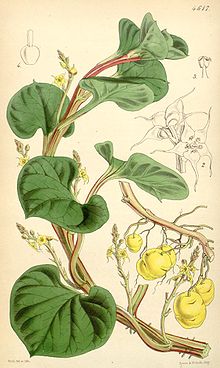

Ullucus is a genus of flowering plants in the family Basellaceae, with one species, Ullucus tuberosus, a plant grown primarily as a root vegetable, secondarily as a leaf vegetable. The name ulluco is derived from the Quechua word ulluku, but depending on the region, it has many different names. These include illaco (in Aymara), melloco (in Ecuador), chungua or ruba (in Colombia), olluco or papa lisa (in Bolivia and Peru), or ulluma (in Argentina).[1][2]

Ulluco is one of the most widely grown and economically important root crops in the Andean region of South America, second only to the potato.[3] The tuber is the primary edible part, but the leaf is also used and is similar to spinach.[4] They are known to contain high levels of protein, calcium, and carotene. Ulluco was used by the Incas prior to the arrival of Europeans in South America.[5] The scrambling herbaceous plant grows up to 50 cm (20 in) high and forms starchy tubers below ground. These tubers are typically smooth and can be spherical or elongated. Generally they are a similar in size to the potato; however, they have been known to grow up to 15 cm (5.9 in) long. Due to the brightly coloured waxy skin in a variety of yellows, pinks and purples, ullucus tubers are regarded as one of the most striking foods in the Andean markets.[6]

Ullucus tuberosus has a subspecies, Ullucus tuberosus subsp. aborigineus, which is considered a wild type. While the domesticated varieties are generally erect and have a diploid genome, the subspecies is generally a trailing vine and has a triploid genome.[7]

Vernacular names

Spanish: olluco, papalisa, ulluco, melloco, chungua, ruba.[7]

English: Ulluco

Origin

It is probable that ulluco was brought into cultivation more than 4000 years ago.[1] Biological material from several coastal Peruvian archaeological sites have been found to contain starch grains and xylem of the ulluco plant, suggesting domestication occurred between the central Andes of Peru and Bolivia.[2] Illustrations and representations of ulluco on wooden vessels (keros), ceramic urns and sculptures have been used to date the presence and importance of these tubers back to 2250 BC.[9]

Although it lost some importance due to the influx of European vegetables following the Spanish conquest in 1531, Ulluco still remains a staple crop in the Andean regions. However, in comparison to the potato which is now cultivated in over 130 countries, outside of South America the ulluco tubers are still relatively unknown.[9] Initial attempts were made to cultivate it in Europe in the 1850s following the potato blights but were not successful on a large scale due to its requirements for cultivation.[10]

Importance and uses

Ullucos are cultivated for their edible tubers by subsistence farmers in high-altitude farming systems around 2,500 to 4,000 m (8,200 to 13,100 ft) above sea level. The tubers are usually eaten in indigenous soups and stews, but more contemporary dishes incorporate them into salads along with the ulluco leaves. These tubers have been eaten in the Andean populations since ancient times and still to this day provide an important protein, carbohydrate and vitamin C source to people living in the high altitude mountainous regions of South America.[1]

The major appeal of ulluco is its crisp texture, which, like the jicama, remains even when cooked.[1] Because of its high water content, ulluco is not suitable for frying or baking, but it can be cooked in many other ways like the potato. In the pickled form, it is added to hot sauces. They are generally cut into thin strips. In order to increase their shelf life, a typical product is produced by the Quechua and Aymara communities in Peru called chuño or lingli. This is produced via a process involving environmental freezing and drying which is usually then ground into a fine flour and added to cooked foods.[11] In Bolivia, they grow to be very colorful and decorative, though with their sweet and unique flavor they are rarely used for decoration. When boiled or broiled they remain moist; the texture and flavor are very similar to the meat of the boiled peanut without the skin. Unlike the peanut meat becoming soft and mushy, ulluco remain firm and almost crunchy.

They are a traditional food in Catholic Holy Week celebrations in Bolivia.

Production

Climate requirements

Ulluco is normally propagated vegetatively by planting small whole tubers. However, they are also easily propagated by stem or tuber cuttings. They prefer cooler climates and will produce much better yields in full sun where summer temperatures are relatively cool. They are also known to grow in hotter regions when covered with shade. They are short day plants which require around 11-13.5 hours of day length. However, due to the inherent diversity of ulluco, sun exposure needs vary among cultivars and location. As the day length shortens, stolons grow out of the stems and then develop into tubers.[4][9]

Fertilization, chemical growth, regulators, field management

Ulluco is grown in the highlands and can survive in altitudes of up to 4,200 m (13,800 ft) above sea level. Indigenous Andean farmers regularly grow a large number of different cultivars of ulluco together in the same fields. Ulluco crop is alternated with two other Andean tuber crops known as oca and mashua. These different tubers are planted together in relatively small field and harvested after approximately eight months. The different species are then separated following harvest.[4]

Harvest and postharvest treatment

Ulluco tubers need to be dug by hand due to their sensitivity to scarring. Due to the importance of their appearance, scuffing of their skin is likely a problem. Under traditional cultivation conditions, yield range from five to nine tons per hectare however in intensive systems, they have been known to reach 40 tons per hectares. These tubers can be stored year-round in the Andes but are best stored in the dark as exposure to the sun can cause fading of their vibrant colouring.[4]

Usually a proportion of the smaller tubers from the harvest are preserved for use as seed tubers the following year. The remainder of the harvest is most often used for consumption however there has been an increasing trend for ulluco use as a cash crop at the markets.

Diseases, viruses, pests

The ulluco is popular among Andean farmers for not having pest and disease issues. However, it has the potential to be host to viruses such as Tymovirus. Tymovirus is similar to the Andean potato latent virus. This could threaten potato crops, as well as other crops in the family Solanaceae (tomatoes, aubergines, peppers). Other species in the family Amaranthaceae (spinach, beet, quinoa) may also be at risk. These viruses pose no risk to human or animal health. The ulluco can be legally imported to the EU with a phytosanitary certificate, but caution is advised.[12] Other viruses of ulluco include the Arracacha virus A, Papaya mosaic virus, Potato leaf roll virus, Potato virus T, Ulluco mild mosaic virus, Ulluco mosaic virus, and Ulluco virus C. Most heirloom ulluco have diseases, but if cultivated from a seed these can be avoided. Ullucus cultivated from clean seed tubers can increase yield by 30-50%.[13] There are clones being developed to eliminate viruses, and these also have been shown to raise yields by 30-50%.[14] The ulluco is susceptible to Verticillium wilt, a soil organism, at low altitudes and high temperatures. There are fumigants available to fight Verticillium, or, for organic farmers, annual rotations into soil that has not been infected for 2–3 years. Ulluco is also susceptible to Rhizoctonia solani, though not as susceptible as the potato. This pathogen can reduce the amount and quality of the yield.[13] Slugs and snails are common pests, though generally only cause cosmetic damage to the ulluco.[15]

Breeding

The ulluco has a limited ability to produce a seed. It was thought to be infertile until researchers in Finland produced a seed in the 1980s. This low fertility poses a challenge when trying to breed this crop. This infertility is thought to be due to the long history of cultivation by planting tubers. However, the ullucus has high genetic diversity, in terms of color, protein content, and tuber yield. It is thought this diversity arises from somatic mutations or from sexual regeneration. Ullucus is primarily bred from seed tubers, but it is also possible by seed and stem cuttings. In New Zealand there have been experiments to induce mutation by gamma radiation and produce more varieties.[13]

Research needs

There may be potential for much higher yields of ulluco and a larger role in the world food system. Potential research into virus free varieties, the photoperiod, and seed producing varieties could expedite this. This could allow for manipulation of colors and other genetic factors. This could also lead to an increased adaptability for ullucus to be grown around the world.[14]

Cultivars

The majority of accessions are diploids (2n=24). Triploids (2n=36) and tetraploids (2n=48) are rare.[16] With 187 accessions evaluated with 18 morphological descriptors, 108 morphotypes or groups have been identified.[17] Considering that the reproduction of the species is vegetative and that the production and use of the germination of botanical seeds is very rare, morphological diversity of the ulluco can be seen as high.

The main characteristics that determine the choice of farmers for cultivars are sweetness, storage capacity before consumption, mucilage content and yield. Skin color is also a key parameter to consider while assessing the potential of the ulluco culture. Red tuber plants are the most frost-resistant and yellow tubers are the most popularly eaten in markets in Ecuador.[18] The attractiveness of the color of cultivars varies among countries and regions. In the New-Zealand market, the preferred skin color was red over plain yellow and mixtures of yellow, green and red.[19] Unusual and unfamiliar colors may explain why some multicolored crops or crops with different colored spots are not appreciated by consumers of New-Zealand.

Nutrition

Fresh tubers of ulluco are a valuable source of carbohydrates, comparable to one of the most world spread root crop, the potato. It contains also high fiber levels, moderate protein and only little fat (< 2%). Regarding the vitamin content, ulluco tubers contain a significant value of vitamin C (11.5 mg/100 g), higher than the commonly eaten vegetables such as carrots (6 mg/100 g) and celery but lower than yams (17.1 mg/100 g) or potato (19.7 mg/100 g). Dietary value variability is pronounced between cultivars.

Little is known about the nutrition content of the leaves. They are nutritious and contain 12% protein dry weight.[7]

Carbohydrates

The carbohydrates of ulluco are composed mainly of starch. But there is also a significant amount of mucilage, a heterogeneous and complex polysaccharide that is recognized as a type of soluble fiber.[20] The mucilage level varies among tubers, high content gives to the raw tubers a gummy texture. Soaked in water or cut very finely are methods used to remove the greatest amount of mucilage from raw tubes,.[21][19] The characteristic is also reduced or lost for cooked tubers.[22] In South America, ulluco tubers with high mucilage content are popular for soups because they add a thicker texture.

Proteins

The proteins contained in the ulluco tubers are a source of amino acids as they contain all the essential amino acids in the human diet: lysine, threonine, valine, isoleucine, leucine, phenylalanine+tyrosine, tryptophan and methionine+cystine.[23][24]

Antioxidant activity

Ulluco is a crop that contains betalains pigments in the base form of betacyanins and acid form of betaxanthins.[24] Thirty two types of betalains have been reported in Ulluco, 20 in the form of betaxanthins and the remaining 12 in the form of betacyanins.[25] Red or purple tuber varieties appear to have a high concentration of betacyanins. A high concentration of betaxanthins is responsible for the yellow or orange coloring of the tubers. In comparison to the three other Andean tuber crops - native potato, oca, and mashua - the antioxidant capacity of the ulluco is low. This is in part explained by the absence of flavonoids, carotenoids and anthocyanins pigments in Ulluco. These pigments are much more abundant sources of antioxidant compounds than betalains.[26] The stability of the betalains pigments makes ulluco a promising industrial crop of natural pigments.[21]

Comparison to staple root foods

This table shows the nutrient content of ulluco next to other major staple root crops – potato, sweet potato, cassava, and yam. Taken individually, potato, sweet potato, cassava, and yam, rank among the most important food crops in the world in respect of annual volume of production.[27] Together, their annual production is about 736.747 million tonnes (FAO, 2008). Comparing to these staple root and tuber crops, the nutritional value of ulluco is good and promising for the geographical extent of the crop.

The nutritional content for each of the crops listed in the table is measured in its raw state, although staple foods are usually sprouted or cooked before consumption rather than consumed raw. The nutritional composition of the product in sprouted or cooked form may deviate from the values presented. The nutrient composition of the ulluco is given within a range, based on the results of nutritional analyses of ulluco grown in South America.

| Ulluco | Potato | Cassava | Sweet Potato | Yam | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nutrient | |||||

| Energy (kJ) | 311 (74.4 kcal) | 322 | 670 | 360 | 494 |

| Water (g) | 83.7 - 87.6 | 79 | 60 | 77 | 70 |

| Carbohydrates (g) | 14.4 - 15.3 | 17 | 38 | 20 | 28 |

| Dietary fiber (g) | 0.9 - 4.9 | 2.2 | 1.8 | 3 | 4.1 |

| Fat (g) | 0.1 - 1.4 | 0.09 | 0.28 | 0.05 | 0.17 |

| Protein (g) | 1.1 - 2.6 | 2.0 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 1.5 |

| Sugar (g) | - | 0.78 | 1.7 | 4.18 | 0.5 |

| Vitamins | |||||

| Retinol (A) (μg) | 5 | - | - | - | - |

| Thiamin (B1) (mg) | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.11 |

| Riboflavin (B2) (mg) | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.03 |

| Niacin (B3) (mg) | 0.2 | 1.05 | 0.85 | 0.56 | 0.55 |

| Vitamin C (mg) | 11.5 | 19.7 | 20.6 | 2.4 | 17.1 |

| Minerals | |||||

| Calcium (mg) | 3 | 12 | 16 | 30 | 17 |

| Iron (mg) | 1.1 | 0.78 | 0.27 | 0.61 | 0.54 |

| Phosphorus (mg) | 28 | 57 | 27 | 47 | 55 |

See also

References

- ^ a b c d Busch, J. and Savage, G.P. (2000). Nutritional composition of ulluco (Ullucus tuberosus) tubers. Proceedings on the Nutrition Society of New Zealand, 25 pp. 55-65.

- ^ a b Arbizu, C., Huamán, Z. and Golmirzaie, A. (1997). ‘Other Andean Roots and Tubers’ in Fuccillo, D., Sears, L. and Stapleton, P. (1st ed.) Biodiversity in Trust: Conservation and Use of Plant Genetic Resources in CGIAR Centres. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press pp.39-56.

- ^ Hermann, M. and Heller, J. (1997). Andean roots and tubers: Ahipa, arracacha, maca and yacon. International Plant Genetic Resources Institute, Rome, Italy.

- ^ a b c d National Research Council (1989). Lost Crops of the Incas: Little-known Plants of the Andes with Promise for Worldwide Cultivation. National Academic Press.

- ^ Hernández Bermejo, J. E. and León, J. (1994). Neglected crops: 1492 from a different perspective. Roma: FAO

- ^ Scheffer, J.J.C., Douglas, J.A., Martin, R.J., Triggs, C.M., Hallow, S. and Deo, B. (2002). Agronomic requirements of ulluco (Ullucus tuberosus) – a South American tuber. Agronomy N.Z. 33, pp 41- 47.

- ^ a b c d National Research Council (U. S.) (1989). Lost Crops of the Incas: Little-known Plants of the Andes with Promise for Worldwide Cultivation. National Academy Press. pp. 105–113.

- ^ Ajacopa, Teofilo Laime (2007). Diccionario Bilingüe Iskay simipi yuyayk'ancha [Quechua-Spanish Dictionary] (PDF) (in Spanish) (2nd ed.). La Paz, Bolivia.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c Sperling, C.R. and King, S.R. (1990). ‘Andean tuber crops: Worldwide potential’ in Janick, J. and Simon, J.E. (ed.) Advances in new crops. Portland: Timber press pp. 428-435.

- ^ Pietilä, L. and Jokela, P. (1990). Seed set of ulluco (ullucus tiberosus Loz.). Variation between clones and enhancement of seed production through the application of plant growth regulators. Euphytica 47, pp. 139-145.

- ^ Flores, H.E., Walker, T.S., Guimarães, R.L. Bais, H.P. and Vivanco, J.M. (2003)/ Andean root and tuber crops: Underground rainbows. Horticultural Science, 38(2) pp.161-167

- ^ Everatt, Matthew (2017). "Preventing the introduction and spread of ulluco viruses" (PDF). planthealthportal.defra.gov.uk. Retrieved 2023-12-24.

- ^ a b c "Growing Ulluco". 26 February 2018.

- ^ a b Innovation, National Research Council (U. S. ) Advisory Committee on Technology (January 1, 1989). Lost Crops of the Incas: Little-known Plants of the Andes with Promise for Worldwide Cultivation. National Academies. ISBN 9780309042642 – via Google Books.

- ^ Scheffer, JJC; Douglas, JA; Martin, RJ; Triggs, CM; Halloy, S; Deo, B (2002). "Agronomic requirements of ulluco (Ullucus tuberosus)- a South American tuber" (PDF). Agronomy Society of New Zealand.

- ^ Mendez M; Arbizu C & M Orrillo (1994). Niveles de ploidía de los ullucus cultivados y silvestres (in Spanish). Valdivia (Chile): Universidad Austral de Chile. Resúmenes de trabajos presentados al VIII Congreso Internacional de Sistemas Agropecuarios y su proyección al tercer milenio. p. 12.

- ^ Malice M; Villarroel Vogt CL; Pissard A; Arbizu C & JP Baudoin (2009). "Genetic diversity of the andean tuber crop species Ullucus tuberosus as revealed by molecular (ISSR) and morphological markers". Belgian Journal of Botany 142(1). pp. 68–82.

- ^ Pietilä, L. & Jokela, P. (1988). "Cultivation of minor tuber crops in Peru and Bolivia". Journal of Agricultural. Science of Finland 60. pp. 87–92.

- ^ a b c Busch, Janette; Savage, Geoffrey (2000). Nutritional composition of ulluco (Ullucus tuberosus) tubers. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society of New Zealand.

- ^ Brito, B.; Villacres, E. & Espín S. (2003). Caracterización físico-química, nutricional y funcional de raíces y tubérculos andinos (in Spanish). Revista Centro Internacional de la Papa.

- ^ a b Manrique, I.; Arbizu, C.; Vivanco, F.; Gonzales, R.; Ramírez, C.; Chávez, O.; Tay, D.; Ellis, D. (2017). Ullucus tuberosus Caldas: colección de germoplasma de ulluco conservada en el Centro Internacional de la Papa (CIP) (in Spanish). Lima (Peru): Centro Internacional de la Papa (CIP). doi:10.4160/9789290604822. hdl:10568/81224. ISBN 9789290604822.

- ^ Brown, N. M. (1997). "Keepers of the Seeds". Research Pennstate 18, 1.

- ^ Cadima, X.; Zeballos, J.; Foronda, E. (2011). Catálogo de Papalisa (PDF) (in Spanish). Cercado (Bolivia): Fundación para la Promoción e Investigación de Productos Andinos (PROINPA).

- ^ a b c Lim, T.K. (2015). Edible Medicinal and Non Medicinal Plants: Volume 9, Modified Stems, Roots, Bulbs. Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht. pp. 741–745.

- ^ Svenson J.; Smallfield B.M.; Joyce NI; Sansom C.; Perry N. (2008). "Betalains in red and yellow varieties of the Andean tuber crop ulluco (Ullucus tuberosus)". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 56 (17). Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 56(17): 7730-7: 7730–7. doi:10.1021/jf8012053. PMID 18662012.

- ^ Campos D; Noratto G; Chirinos R; Arbizu C; Roca W & L Cisneros-Zevallos (2006). Antioxidant capacity and secondary metabolites in four species of Andean tuber crops: Native potato (Solanum sp.), mashua (Tropaeolum tuberosum Ruíz & Pavón), oca (Oxalis tuberosa Molina) and ulluco (Ullucus tuberosus Caldas). Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 86(10): 1481-1488.

- ^ Q. Liu; J. Liu; P. Zhang; S. He (2014). Root and Tuber Crops. Encyclopedia of Agriculture and Food Systems. pp. 46–61.

- ^ Reyes García, María; Gómez-Sánchez Prieto, Iván; Espinoza Barriento, Cecilia (2017). Tablas peruanas de composición de alimentos (in Spanish). Lima: Ministerio de Salud, Instituto Nacional de Salud. pp. 66–67.

- ^ ""Nutrient data laboratory". United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 10 August 2016.