Occupation of Ma'an

Occupation of Ma'an | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1918–1923 | |||||||||||||||||||

Flag | |||||||||||||||||||

Sanjak of Ma'an in the 19th century | |||||||||||||||||||

| Status | Occupied territory with competing claims | ||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Ma'an | ||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Arabic | ||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||

• Established | 1918 | ||||||||||||||||||

• Disestablished | 1923 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||||||

• 1921 | 10,000 | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

The Occupation of Ma'an was the post-World War I occupation of the Sanjak of Ma'an, which straddled the regions of Syria and Arabia, by members of the Hashemite family, who came to power in various regions of the Near East and Arabia; they were King Hussein in the Kingdom of Hejaz, Emir Faisal representing the Arab government in Damascus (Occupied Enemy Territory Administration East and later the Arab Kingdom of Syria) and Abdullah, who was to become Emir of Transjordan.[1][2][3] The region includes the governorates of Ma'an and Aqaba, today in Jordan, as well as the area which was to become a large part of the Israeli Southern District, including the city of Eilat.

The matter developed into an international dispute between the modern states of Saudi Arabia and Jordan, and was also relevant to the inclusion of the Negev region into what became the modern country state of Israel. Dr. Benjamin Shwadran, in his history of Jordan, described the matter as "one of the most confused chapters in that country's history";[4][5] in question was to whom did the Ma'an sanjak (including the towns of Ma'an and Aqaba) legitimately belong.[5]

The claims

Status under Ottomans

In June 1934 the Permanent Mandates Commission asked the British for "information as to the line of demarcation between the vilayet of the Hejaz and that of Syria in the time of the Ottoman Administration";[6][7] the report was delivered in the 1934 British Mandatory annual report and stated that:[8][9]

- in 1893 the Ma'an-Aqaba area was part of the vilayet of Damascus

- in 1904 the sub-district of Aqaba was transferred to the vilayet of Hijaz

- between 1904 and 1910 the independent sanjak of Medina, including Aqaba, was formed

- between 1910 and 1915 the Aqaba sub-district was reattached to the vilayet of Syria

- by the summer of 1915 it had reverted to the independent sanjak of Medina

According to Hasan Kayali, in July 1910, the time of the Young Turks and the second constitutional experiment, the Ottomans changed the administrative status of Medina from the sanjak of the Hejaz Vilayet to the independent sanjak with a view to strengthening control from the center.[10] In 1915, the Ottoman authorities, for military reasons, pushed the southern boundary of the Syria Vilayet far into the historical Hejaz region, up to a line from al-Wajh to Mada'in Saleh (Al-'Ula).[11][12] The international law professor Suzanne Lalonde writes that the Sanjak of Ma'an was part of the Vilayet of Damascus until 1906 when responsibility was transferred to the Vilayet of Hejaz.[13] According to professor Gideon Biger, in 1908 the Ottoman regime had decided to change its own internal division, and to move the district of Ma’an from the province of Hijaz to the province of E-Sham (Syria)(the Vilayet of Damascus), which was centered on Damascus, although it is not clear whether the move was actually implemented.[14] (Biger also states that Hussein claimed that Ma'an was supposed to be added to E-Sham (Syria) in 1908, but this appears to be an error)[14]

Status during the Arab Revolt

The area in the Sykes–Picot Agreement map |

Emir Faisal had led the Arab Revolt, which moved into the region with the 1917 Battle of Aqaba. Faisal went on to head the Arab-British military administration in the OETA East. After the July 1917 Battle of Aqaba, Gilbert Clayton wrote to Reginald Wingate:

The occupation of Aqaba by Arab troops might well result in the Arabs claiming that place hereafter, and it is by no means improbable that after the war Aqaba may be of considerable importance to the future defence scheme of Egypt. It is thus essential that Aqaba should remain in British hands after the war.[15]

Following the Battle of Aqaba, according to the official British history of the war: "It was decided that Emir Faisal should become in effect an army commander under Sir Edmund Allenby's orders. All Arab operations North of Ma'an were to be carried out by him under the direction of the British Commander-in-Chief. South of Ma'an the High Commissioner Sir Reginald Wingate was still to act as adviser to the Emirs Ali and Abdullah and to be responsible for their supply."[16] One motivating factor for this British position was to avoid the Ottomans' connecting the Red Sea with the Mediterranean by rail, thereby creating competition to the Suez Canal.[17][18] In 1917 Hussein claimed that the Islamic holy land of the Hejaz extended north beyond Aqaba, that Medina would be cut off without access to the port of Aqaba and that he had won the area through conquest.[19]

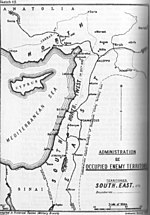

Status during OETA

The "confusion" over the region began in the OETA period; the British Foreign Office later noted that "Ma'an may or may not have been intended to fall within that area."[21] The actual definition of OETA East, declared on 23 October 1918, was: "all districts East of (a) and (b) above, up to the northern limits of the Kazas of Jebel Seman and El Bab" where a and b were OETA South and North respectively.[22][23]

Lalonde states that there was no official map to go with the OETA definitions although it seemed likely that the British had relied on the 1918 map of Palestine published by the Survey Department of Egypt for delineating OETA South (Palestine therein drops to the border with Egypt rather than the truncated version that appears in the Sykes-Picot map).[24] According to Antonius and Leatherdale, OETA East included the Ma'an region, including Aqaba.[19][25] However, he noted that "this is a matter of some confusion",[26] and acknowledged that the opposite interpretation is held by Frischwasser-Ra'anan.[27][26]

Kingdom of Syria

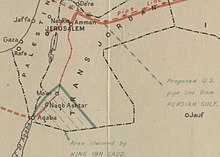

On 2 July 1919, the Syrian National Congress in Damascus defined their southern border as "a line running from Rafah to Al-Jauf and following the Syria-Hejaz border below 'Aqaba".[28]

The Negev

Although historically connected to the Ma'an region, the Negev was added to the proposed area of Mandatory Palestine, later to become Israel, on 10 July 1922, having been conceded by British representative St John Philby "in Trans-Jordan’s name". Much of the region had been part of the sanjak of Ma'an.[29]

British views and actions

Following the French occupation of only the northern part of the Syrian Kingdom, Transjordan was left in a period of interregnum. A few months later, Abdullah, the second son of Sharif Hussein, arrived into Transjordan.

In the 16 September 1922 Trans-Jordan memorandum, approved by the Council of the League of Nations, Transjordan was defined as: "all territory lying to the east of a line drawn from a point two miles west of the town of Akaba on the Gulf of that name up... to the Syrian Frontier."[30]

The British claimed that they always considered the area as being outside Hejaz. In 1925 the British acknowledged that for some period they had "acquiesced in the status of the Ma'an and Akaba districts remaining indeterminate pending a final delimitation of the frontier".[31] On 24 June 1925, Secretary of State for the Colonies Leo Amery stated in Parliament that "His Majesty's Government have never regarded the town of Akaba as falling within the limits of the Hejaz, nor has its occupation by the Hejaz ever had their formal consent."[32][33] Author Gary Troeller, noting that Shwadran's 1959 work makes extensive use of secondary and official published sources and claiming to take account of records unpublished at that time, opines that both Ma'an and Aqaba were part of the Hejaz.[34]

In 1925, the matter was raised at the 9th session of the Permanent Mandates Commission, in response to the British report stating that "in August the region about Ma'an, although included in the area under the British mandate, had passed temporarily under the control of the King of the Hedjaz". In response, Colonel Stewart Symes noted that: "The fact that the Amir Abdullah was the son of King Hussein necessitated a certain tact in dealing with [Hussein's] encroachment [into the Ma'an region]."[35][6][8]

Transjordan announcement

On 27 June 1925, after Hussein had abdicated and fled the Hejaz, but whilst King Ali remained in Mecca, Abdullah issued the following proclamation:[36][37]

On the authority of His Hashemite Majesty King Ali, King of the Holy Hejaz, we declare the districts of Maan and Akaba to be part of the Amirate of Transjordan.

Saudi claim

The matter was discussed in the period of negotiations that led to the May 1927 Treaty of Jeddah. However, the British government dropped their insistence that Ibn Saud formally recognize Aqaba and Ma'an as part of Transjordan; instead this was dealt with via a separate exchange of letters, between 19 and 21 May 1927, in which Clayton stated the British position and Ibn Saud agreed to respect the status quo.[38]

A January 12, 1940 memorandum prepared by the Eastern Department of the Foreign Office, entitled "Ibn Saud's claim to Akaba and Maan" discussed:[39]

- (1) The historical and administrative position of Akaba and Maan in the Ottoman empire.

- (2) The manner in which question of sovereignty has been affected by conquest, occupation and administration, and by certain measures of British and allied policy, during and since the war of 1914-18.

The Saudi Arabia claim to Aqaba and Ma'an was finally settled and the border delineated in 1965.[40]

References

- ^ Wilson 1990, p. 100.

- ^ Baker 1979, p. 220: "The British had moved in to take advantage of the situation created by Husain's presence in Aqaba and pressed for the annexation of the Hejaz Vilayet of Ma'an to the mandated territory of Transjordan. This disputed area, containing Maan, Aqaba and Petra, had originally been part of the Damascus Vilayet during Ottoman times, though boundaries had never been very precise. It was seized first by the Army as it pushed north from Aqaba after 1917 and had then been included in O.E.T.A. East and, later, in Faisal's kingdom of Syria. Husain, however, had never accepted this and had stationed a Vali alongside Faisal's administrator, but the two men had worked in harmony so that the dispute never came to an open struggle. After Faisal's exile, the French mandate boundary had excluded this area and the British then considered it to be part of the Syrian rump which became Transjordan, though nothing was done to realise that claim, so Hejaz administration held de facto control. Britain had, however, made its position clear in August 1924 when it cabled Bullard: "Please inform King Hussein officially that H.M.G. cannot acquiesce in his claim to concern himself directly with the administration of any portion of the territory of Transjordan for which H.M.G. are responsible under the mandate for Palestine"

- ^ Leatherdale 1983, p. 41-42: "By 1919 British forces had withdrawn from this easterly area leaving the local administrative arrangements confused. In Aqaba, a qaimmaqam (district governor) had been appointed who disregarded both Husein in Mecca and Feisal in Damascus with impunity. Another qaimmaqam had been appointed by Feisal at Maan, despite Husein having instructed the official at Aqaba to extend his jurisdiction over Maan. Britain, at the same time, decided to develop a joint Arab-Palestine free port in the Aqaba area, though there existed strong doubts over Aqaba's suitability as a future port."

- ^ Shwadran 1959, p. 154-157.

- ^ a b Troeller 2013, p. 222.

- ^ a b Troeller 2013, p. 224-226.

- ^ MINUTES OF THE TWENTY-FIFTH SESSION, C.259. M.108. 1934, Held at Geneva from May 30th to June 12th, 1934, REPORT TO THE COUNCIL ON THE WORK OF THE SESSION, Page 149, II. SPECIAL OBSERVATIONS. 2. Frontiers. "The Commission would welcome in the next report a statement concerning the frontier between Trans-Jordan and Sa'udi Arabia and also information as to the line of demarcation between the vilayet of the Hejaz and that of Syria in the time of the Ottoman Administration."

- ^ a b Shwadran 1959, p. 157.

- ^ Report by His Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland to the Council of the League of Nations on the Administration of Palestine and Trans-Jordan for the year 1934, pages 241 and 242 (see discussion of this at the 1935 PMC)

- ^ Kayali 1997, p. 160.

- ^ Gil-Har 1992, p. 374; Gil-Har quotes Mallet's 1926 memorandum..

- ^ Guckian 1985, p. 181.

- ^ Lalonde 2002, p. 91.

- ^ a b Biger 2004, p. 160.

- ^ Anderson 2014, p. 295.

- ^ Macmunn & Falls 1930.

- ^ Leatherdale 1983, p. 56, footnote 31.

- ^ Frischwasser-Ra'anan 1955, p. 38.

- ^ a b Leatherdale 1983, p. 41.

- ^ Macmunn & Falls 1930, p. 606-607.

- ^ Guckian 1985, p. 182.

- ^ Alsberg 1980, p. 87.

- ^ thegazette.co.uk/. "The London Gazette". The Gazette Official Public Record. p. 10191. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

This content is available under the Open Government Licence v3.0 Archived 2017-06-28 at the Wayback Machine.

This content is available under the Open Government Licence v3.0 Archived 2017-06-28 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Lalonde 2002, p. 94.

- ^ Antonius 1938, p. 278: "the second, known as O.E.T.A. East, comprised the interior of Syria from 'Aqaba to Aleppo and was Arab"

- ^ a b Leatherdale 1983, p. 56.

- ^ Frischwasser-Ra'anan 1955, p. 153.

- ^ Antonius 1938, p. 439, appendix G.

- ^ Biger 2004, p. 181, references 10 July 1922 meeting notes, file 2.179, CZA: "Sovereignty over the Arava, from the south of the Dead Sea to Aqaba, was also discussed. Philby agreed, in Trans-Jordan’s name, to give up the western bank of Wadi Arava (and thus all of the Negev area). Nevertheless, a precise borderline was still not determined along the territories of Palestine and Trans-Jordan. Philby’s relinquishment of the Negev was necessary, because the future of this area was uncertain. In a discussion regarding the southern boundary, the Egyptian aspiration to acquire the Negev area was presented. On the other hand the southern part of Palestine belonged, according to one of the versions, to the sanjak (district) of Ma’an within the vilayet (province) of Hejaz. King Hussein of Hijaz demanded to receive this area after claiming that a transfer action, to add it to the vilayet of Syria (A-Sham) was supposed to be done in 1908. It is not clear whether this action was completed. Philby claimed that Emir Abdullah had his father’s permission to negotiate over the future of the sanjak of Ma’an, which was actually ruled by him, and that he could therefore ‘afford to concede’ the area west of the Arava in favour of Palestine. This concession was made following British pressure and against the background of the demands of the Zionist Organization for direct contact between Palestine and the Red Sea. It led to the inclusion of the Negev triangle in Palestine’s territory, although this area was not considered as part of the country in the many centuries that preceded the British occupation."

- ^

Works related to Transjordan Memorandum at Wikisource

Works related to Transjordan Memorandum at Wikisource

- ^ Hansard: “It is true that for some time [HMG] acquiesced in the status of the Ma'an and Akaba districts remaining indeterminate pending a final delimitation of the frontier”

- ^ AKABA, HC Deb 24 June 1925 vol 185 cc1504-5

- ^ Shwadran 1959, p. 156.

- ^ Troeller 2013, pp. 224–226.

- ^ "The Ma'an Region", League of Nations 9th session- Minutes of the Permanent Mandates Commission

- ^ Troeller 2013, p. 226.

- ^ Guckian 1985, p. 191.

- ^ Silverfarb 1982, p. 281.

- ^ See British Foreign office memorandum January 1940 regarding the border between Jordan and Saudi Arabia, sourced from: Eastern Division, Foreign Office (2017-05-23). "Coll 6/66 'Saudi-Arabia: Saudi-Transjordan Frontier'". Qatar National Library. pp. 7–10. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- ^ "International Boundary Study, No. 60 – December 30, 1965, Jordan – Saudi Arabia Boundary" (PDF). US Department of State. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

Bibliography

English-language

- Alsberg, Avraham P. [in German] (1980). "Delimitation of the eastern border of Palestine". Zionism. Vol. 2. Institute for Zionist Research Founded in Memory of Chaim Weizmann. pp. 87–98. doi:10.1080/13531048108575800.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - Anderson, Scott (6 March 2014). Lawrence in Arabia: War, Deceit, Imperial Folly and the Making of the Modern Middle East. Atlantic Books. p. 295. ISBN 978-1-78239-201-9.

- Antonius, George (1938). The Arab Awakening: The Story of the Arab National Movement. Hamish Hamilton. ISBN 978-0-7103-0673-9.

- Baker, Randall (1979). King Husain and the Kingdom of Hejaz. The Oleander Press. p. 220. ISBN 978-0-900891-48-9.

- Biger, Gideon (2004). The Boundaries of Modern Palestine, 1840-1947. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-76652-8.

- Frischwasser-Ra'anan, Heinz Felix (1955). The Frontiers of a Nation: A Re-examination of the Forces which Created the Palestine Mandate and Determined Its Territorial Shape. Batchworth Press. ISBN 978-0-598-93542-7.

- Gil-Har, Yitzhak (1992). "Delimitation Boundaries: Trans-Jordan and Saudi Arabia". Middle Eastern Studies. 28 (2): 374–384. doi:10.1080/00263209208700906. JSTOR 4283498.

- Guckian, Noel Joseph (1985). British Relations with Trans-Jordan, 1920-1930 (PhD). Department of International Politics, Aberystwyth University.

- Kayali, Hasan (3 September 1997). "Extension of Ottoman Influence in the Hijaz, Medina: An Ottoman Outpost in the Hijaz". Arabs and Young Turks: Ottomanism, Arabism, and Islamism in the Ottoman Empire, 1908-1918. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-20446-1.

- Lalonde, Suzanne N. (6 December 2002). Determining Boundaries in a Conflicted World: The Role of Uti Possidetis. McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP. ISBN 978-0-7735-7049-8.

- Leatherdale, Clive (1983). Britain and Saudi Arabia, 1925-1939: The Imperial Oasis. Psychology Press. pp. 41–42. ISBN 978-0-7146-3220-9.

- Nevo, J. (15 November 1996). King Abdallah and Palestine: A Territorial Ambition. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 3–. ISBN 978-0-230-37883-4.

- Shwadran, Benjamin (1959). Jordan: A State of Tension. Council for Middle Eastern Affairs Press. ISBN 978-1-258-43247-8.

- Silverfarb, D. (1982). "The Treaty of Jiddah of May 1927". Middle Eastern Studies. 18 (3): 276–285. doi:10.1080/00263208208700511. JSTOR 4282893.

- Troeller, Gary (23 October 2013). The Birth of Saudi Arabia: Britain and the Rise of the House of Sa'ud. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-16198-9.

- Wilson, Mary Christina (1990). King Abdullah, Britain and the Making of Jordan. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-39987-6.

Arabic-language

- Mohammad Abdul-Karim Mahaftha (2004), The British Role in Subjoining Ma'an and Aqaba to Trans-Jordan Administration, 1925 [Arabic title الدور البريطاني في إلحاق معان والعقبة بإدارة شرقي الأردن عام]

Sources by involved parties

- Victor Mallet, Foreign Office Eastern Department Second Secretary, memorandum, 'Transjordan's Claim to Akaba and Maan', 22 October 1926, FO E/5967/572/91: 371/11444 (quoted in Leatherdale)

- Macmunn, G. F.; Falls, C. (1930). Military Operations: Egypt and Palestine, From June 1917 to the End of the War Part II. History of the Great War based on Official Documents by Direction of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. II. accompanying Map Case (1st ed.). London: HMSO. OCLC 656066774.