Nylon 6

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name Poly(azepan-2-one); poly(hexano-6-lactam) | |

| Systematic IUPAC name Poly[azanediyl(1-oxohexane-1,6-diyl)] | |

| Other names Polycaprolactam, polyamide 6, PA6, poly-ε-caproamide, Perlon, Dederon, Capron, Ultramid, Akulon, Nylatron, Kapron, Alphalon, Tarnamid, Akromid, Frianyl, Schulamid, Durethan, Technyl, Nyorbits ,Winmark Polymers | |

| Identifiers | |

| ChemSpider |

|

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.124.824 |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| Properties | |

| (C6H11NO)n | |

| Density | 1.084 g/mL [citation needed] |

| Melting point | 218.3 °C (493 K) |

| Hazards | |

| 434 °C; 813 °F; 707 K | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

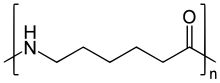

Nylon 6 or polycaprolactam is a polymer, in particular semicrystalline polyamide. Unlike most other nylons, nylon 6 is not a condensation polymer, but instead is formed by ring-opening polymerization; this makes it a special case in the comparison between condensation and addition polymers. Its competition with nylon 6,6 and the example it set have also shaped the economics of the synthetic fibre industry. It is sold under numerous trade names including Perlon (Germany), Dederon (former East Germany),[1] Nylatron, Capron, Ultramid, Akulon, Kapron (former Soviet Union and satellite states), Rugopa (Turkey) and Durethan.

History

Polycaprolactam was developed by Paul Schlack at IG Farben in late 1930s (first synthesized in 1938) to reproduce the properties of Nylon 66 without violating the patent on its production. (Around the same time, Kohei Hoshino at Toray also succeeded in synthesizing nylon 6.) It was marketed as Perlon, and industrial production with a capacity of 3,500 tons per year was established in Nazi Germany in 1943, using phenol as a feedstock. At first, the polymer was used to produce coarse fiber for artificial bristle, then the fiber quality was improved, and Germans started making parachutes, cord for aircraft tires and towing cables for gliders.

The Soviet Union began its development of an analog in the 1940s, while negotiating with Germany on building an IG Farben plant in Ukraine,[when?] basic scientific work was ongoing in 1942. The production only started in 1948 in Klin, Moscow Oblast, after USSR obtained the 2000 volumes of IG Farben, and 10,000 volumes of AEG technical documentation,[2] as a result of victory in the World War II.

Synthesis

Nylon 6 can be modified using comonomers or stabilizers during polymerization to introduce new chain end or functional groups, which changes the reactivity and chemical properties. It is often done to change its dyeability or flame retardance.[3] Nylon 6 is synthesized by ring-opening polymerization of caprolactam. Caprolactam has 6 carbons, hence Nylon 6. When caprolactam is heated at about 533 K in an inert atmosphere of nitrogen for about 4–5 hours, the ring breaks and undergoes polymerization. Then the molten mass is passed through spinnerets to form fibres of nylon 6.

During polymerization, the amide bond within each caprolactam molecule is broken, with the active groups on each side re-forming two new bonds as the monomer becomes part of the polymer backbone. Unlike nylon 6,6, in which the direction of the amide bond reverses at each bond, all nylon 6 amide bonds lie in the same direction (see figure: note the N to C orientation of each amide bond).

Properties

Nylon 6 fibres are tough, possessing high tensile strength, elasticity and lustre. They are wrinkleproof and highly resistant to abrasion and chemicals such as acids and alkalis. The fibres can absorb up to 2.4% of water, although this lowers tensile strength. The glass transition temperature of Nylon 6 is 47 °C.

As a synthetic fibre, Nylon 6 is generally white but can be dyed in a solution bath prior to production for different color results. Its tenacity is 6–8.5 gf/D with a density of 1.14 g/cm3. Its melting point is at 215 °C and can protect heat up to 150 °C on average.[4]

Biodegradation

Flavobacterium sp. [85] and Pseudomonas sp. (NK87) degrade oligomers of Nylon 6, but not polymers. Certain white rot fungal strains can also degrade Nylon 6 through oxidation. Compared to aliphatic polyesters, Nylon 6 has been said to have poor biodegradability. Strong interchain interactions from hydrogen bonds between molecular nylon chains is said to be the cause by some sources.[5]

However, in 2023 a team of Northwestern University chemists led by Linda Broadbelt and Tobin J. Marks developed rare earth metallocene catalysts that rapidly break Nylon 6 down back to caprolactam at 220°C, which is considered mild conditions.[6][7][8]

Production in Europe

At present, polyamide 6 is a significant construction material used in many industries, for instance in the automotive industry, aircraft industry, electronic and electrotechnical industry, clothing industry and medicine. Annual demand for polyamides in Europe amounts to a million tonnes. They are produced by all leading chemical companies.

The largest producers of polyamide 6 in Europe:[9]

- Fibrant, 260,000 tonnes per year

- BASF, 240,000 tonnes per year

- Lanxess, 170,000 tonnes per year

- Radici, 125,000 tonnes per year

- DOMO, 100,000 tonnes per year

- Grupa Azoty, 100,000 tonnes per year[10][11]

References

- ^ Rubin, E. (2014), Synthetic Socialism: Plastics and Dictatorship in the German Democratic Republic. The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1469615103

- ^ Zaharov, V.V. (2007). Советская военная администрация в Германии 1945-1949: Деятельность Управления СВАГ по изучению достижений немецкой науки и техники в Советской зоне оккупации Германии [Soviet military administration in Germany 1945-1949: Activities of the SMAG Directorate for studying the achievements of German science and technology in the Soviet zone of occupation of Germany] (in Russian). Moscow: ROSSPEN, Russian State Archive. p. 65. ISBN 978-5-8243-0882-2.

- ^ "Synthesis of Modified Polyamides (Nylon 6)", NPTEL (National Programme On Technology Enhanced Learning), retrieved May 9, 2016

- ^ ”Polyamide Fiber Physical and Chemical Properties of Nylon 6”, textilefashionstudy.com, retrieved May 9, 2016.

- ^ Tokiwa, Y.; Calabia, B. P.; Ugwu, C. U.; Aiba, S. (2009). "Biodegradability of Plastics". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 10 (9): 3722–42. doi:10.3390/ijms10093722. PMC 2769161. PMID 19865515.

- ^ "New Catalyst Completely Breaks Down Durable Plastic Pollution in Minutes". 3 December 2023.

- ^ Ye, Liwei; Liu, Xiaoyang; Beckett, Kristen; Rothbaum, Jacob O.; Lincoln, Clarissa; Broadbelt, Linda J.; Kratish, Yosi; Marks, Tobin J. (2023-04-27), Catalyst Design to Address Nylon Plastics Recycling, doi:10.26434/chemrxiv-2023-h91np, retrieved 2024-10-09

- ^ Ye, Liwei; Liu, Xiaoyang; Beckett, Kristen B.; Rothbaum, Jacob O.; Lincoln, Clarissa; Broadbelt, Linda J.; Kratish, Yosi; Marks, Tobin J. (January 2024). "Catalyst metal-ligand design for rapid, selective, and solventless depolymerization of Nylon-6 plastics". Chem. 10 (1): 172–189. Bibcode:2024Chem...10..172Y. doi:10.1016/j.chempr.2023.10.022. ISSN 2451-9294.

- ^ "Segment Tworzywa 2015" (PDF) (in Polish). static.grupaazoty.com. Retrieved 2016-04-12.

- ^ "Alphalon™ (PA6)" (in Polish). att.grupaazoty.com. Archived from the original on 2016-04-26. Retrieved 2016-04-12.

- ^ "Grupa Azoty: Nowa wytwórnia pozwoli zająć pozycję 2. producenta poliamidu w UE" (in Polish). wyborcza.biz. Retrieved 2016-04-12.