Novi Pazar

Novi Pazar Нови Пазар (Serbian) | |

|---|---|

| Град Нови Пазар Grad Novi Pazar City of Novi Pazar | |

Panorama of Novi Pazar Novi Pazar Fortress | |

| Coordinates: 43°08′16″N 20°30′58″E / 43.13778°N 20.51611°E | |

| Country | |

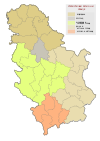

| Region | Šumadija and Western Serbia |

| District | Raška District |

| Founded | 1461 |

| Settlements | 100 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Nihat Biševac (SDP) |

| Area | |

| • Rank | 31st in Serbia |

| • Urban | 15.34 km2 (5.92 sq mi) |

| • Administrative | 742 km2 (286 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 477 m (1,565 ft) |

| Population (2022 census)[2] | |

| • Rank | 10th in Serbia |

| • Urban | 71,462 |

| • Urban density | 4,700/km2 (12,000/sq mi) |

| • Administrative | 106,720 |

| • Administrative density | 140/km2 (370/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 36300 36302 36303 36316 36318 36319 36322 |

| Area code | +381(0)20 |

| ISO 3166 code | SRB |

| Car plates | NP |

| Climate | Cfb |

| Website | www |

Novi Pazar (Serbian Cyrillic: Нови Пазар) is a city located in the Raška District of southwestern Serbia. As of the 2022 census, the urban area has 71,462 inhabitants, while the city administrative area has 106,720 inhabitants.[3] The city is the cultural center of the Bosniaks in Serbia and of Sandžak.[4] A multicultural area of Muslims and Orthodox Christians, many monuments of both religions, like the Altun-Alem Mosque and the Church of the Holy Apostles Peter and Paul, are located in the region which has a total of 30 protected monuments of culture.[5]

Name

During the 14th century under the old Serbian fortress of Stari Ras, an important market-place named Trgovište started to develop. By the middle of the 15th century, in the time of the final Ottoman Empire conquest of Old Serbia, another market-place was developing some 11 km to the east. The older place became known as Staro Trgovište (Old Trgovište, Turkish: Eski Pazar) and the younger as Novo Trgovište (New Trgovište, Turkish: Yeni Pazar). The latter developed into the modern city of Novi Pazar.

The name "Novi Pazar" (meaning 'New Bazaar') was derived from the Serbian name Novo Trgovište, via the Turkish name Yeni Pazar, which is itself derived from bazaar (from Persian بازار (bāzār) 'market'; from Pahlavi بهاچار (bahā-chār) 'place of prices').[6] The city is known as Pazari i Ri or Tregu i Ri[7] in Albanian and simply Novi Pazar in Bosnian. Aside from that it is still known as Yeni Pazar in modern-day Turkey.

Geography

Novi Pazar is located in the valleys of the Jošanica, Raška, Deževska, and Ljudska rivers. It lies at an elevation of 496m, in the southeast Raška region. The city is surrounded by the Golija and Rogozna mountains, and the Pešter plateau lies to the west. The total area of the city administrative area is 742 km2. It contains 100 settlements, mostly small and spread over hills and mountains surrounding the city. The largest village is Mur, with over 3000 residents.[citation needed]

Climate

Novi Pazar has a humid continental climate (Köppen climate classification: Dfb) typical of the hilly Raška region. It is generally cooler than Serbia's other major cities, though still significantly warmer than the neighboring town of Sjenica.

| Climate data for Novi Pazar | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 2.7 (36.9) |

5.6 (42.1) |

11.1 (52.0) |

15.5 (59.9) |

20.1 (68.2) |

23.6 (74.5) |

26.1 (79.0) |

26.4 (79.5) |

22.7 (72.9) |

16.5 (61.7) |

8.8 (47.8) |

4.3 (39.7) |

15.3 (59.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −0.6 (30.9) |

1.6 (34.9) |

6.3 (43.3) |

10.2 (50.4) |

14.6 (58.3) |

18.0 (64.4) |

20.1 (68.2) |

20.1 (68.2) |

16.7 (62.1) |

11.4 (52.5) |

5.2 (41.4) |

1.2 (34.2) |

10.4 (50.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −3.9 (25.0) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

1.5 (34.7) |

5.0 (41.0) |

9.2 (48.6) |

12.5 (54.5) |

14.1 (57.4) |

13.8 (56.8) |

10.7 (51.3) |

6.4 (43.5) |

1.6 (34.9) |

−1.8 (28.8) |

5.6 (42.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 71 (2.8) |

64 (2.5) |

66 (2.6) |

74 (2.9) |

92 (3.6) |

78 (3.1) |

68 (2.7) |

62 (2.4) |

69 (2.7) |

80 (3.1) |

93 (3.7) |

83 (3.3) |

900 (35.4) |

| Source: [8] | |||||||||||||

History

One of the oldest monuments of the area is the Church of the Holy Apostles Peter and Paul first built in the Roman era and reconstructed in the 9th century. Over many centuries the city area of Stari Ras was a borderline contested by the First Bulgarian Empire, Serbian Principality and Byzantine Empire.

Since the late-12th century, the region of modern Novi Pazar served as the principal province of the Serbian realm. It was an administrative division, usually under the direct rule of the monarch and sometimes as an appanage. It was the crownland, seat or appanage of various Serbian states throughout the Middle Ages, including the Serbian Kingdom (1217–1345) and the Serbian Empire (1345–1371). In 1427, the region and the remnant of Ras, as part of the Serbian Despotate, was ruled by Serbian despot Đurađ Branković. One of the markets was called "despotov trg" (Despot's square).[9] In 1439, the region was captured by the Ottoman Empire, but was reconquered by the Serbian Despotate in 1444. In the summer of 1455, the Ottomans conquered the region again, and named the settlement of Trgovište Eski Bazar (Old Market). Novi Pazar was formally founded as a city in its own right in 1461 by Ottoman general Isa-Beg Ishaković, the Bosnian governor of the district (sanjak) who also founded Sarajevo.[10] Ishaković decided to establish a new town on the area of Trgovište as an urban center between Raška and Jošanica, where at first he built a mosque, a public bath, a marketplace, a hostel, and a compound.[citation needed]

The town was the capital of the Sanjak of Novi Pazar during Ottoman rule. From 1878 to 1908, it was controlled by Austria-Hungary, and from 1908 to 1913, it was again part of the Ottoman empire under the Kosovo vilayet. It became part of the Kingdom of Serbia during the First Balkan War in 1912, and then in 1918 the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.[11]

The area has traditionally had a large number of Albanians and Muslim Slavs with a different culture from the Orthodox Serbs.[12] In May 1901, Albanians pillaged and partially burned the cities of Novi Pazar, Sjenica and Pristina, and massacred Serbs in the area of Ibar Kolašin.[13] A contemporary report stated that when the Serb forces entered the Sandjak of Novi Pazar, they "pacified" the Albanians.[14]

In the Battle for Novi Pazar, fought at the end of 1941 during the Second World War, the Chetniks, initially supported by the Partisans, unsuccessfully tried to capture the city.[citation needed] Following the overthrow of Slobodan Milošević on 5 October 2000, newly elected Prime Minister of Serbia Zoran Đinđić made considerable efforts to help economically the whole area of Novi Pazar. Also, with the help of Đinđić, the International University of Novi Pazar was founded in 2002. He made close relations with the leaders of Bosniaks, as part of his wider plan to reform Serbia.[15] Twelve years following his assassination, the Novi Pazar Assembly decided to rename one street in his name.[16]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1948 | 11,992 | — |

| 1953 | 14,104 | +17.6% |

| 1961 | 20,706 | +46.8% |

| 1971 | 28,950 | +39.8% |

| 1981 | 41,099 | +42.0% |

| 1991 | 51,749 | +25.9% |

| 2002 | 54,604 | +5.5% |

| 2011 | 66,527 | +21.8% |

| 2022 | 71,462 | +7.4% |

| Source: [17] | ||

According to the 2022 census, the municipality of Novi Pazar has 106,720 inhabitants, while the city itself has 71,462 inhabitants.[3] A total of 68.47% of population live in urban area of the city. The population density is 135.32 inhabitants per square kilometer.[18] Novi Pazar has 23,022 households with 4,36 members on average; the number of homes is 28,688.[19]

Religion structure in the city of Novi Pazar is predominantly Muslim (82,710), with Serbian Orthodox (16,051), Atheists (71), Catholics (51), and other minority groups.[20] Most of the population speaks either Bosnian (74,501) or Serbian (23,406).[20]

The composition of population by sex and average age:[20]

- Male - 49,984 (32.90 years) and

- Female - 50,426 (34.14 years).

A total of 33,583 citizens (older than 15 years) have secondary education (44.41%), while the 7,351 citizens have higher education (9.72%). Of those with higher education, 5,005 (6.62%) have university education.[21]

Ethnic composition

From the 15th century to the Balkan Wars, Novi Pazar was the capital of the sanjak of Novi Pazar. Typically, like other centres of the wider area, its composition was multiethnic, with Albanians, Serbs and Slavic-speaking Muslims as the largest ethnic groups of the city.[22] The Ottoman travel writer Evliya Çelebi noted that it was one of the most populated towns in the Balkans in the 17th century. Jews also lived in the city until World War II.[23] The entire Jewish population of Novi Pazar - 221 individuals, were imprisoned, sent to the concentration camp Staro Sajmište and killed during the rule of Aćif Hadžiahmetović.[24] The ethnic composition of the city administrative area:[25][26]

| Ethnic group | Population 1953[27] |

Population 1961[28] |

Population 1971[29] |

Population 1981[30] |

Population 1991[31] |

Population 2002[32] |

Population 2011[33] |

Population

2022[34] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bosniaks | - | - | - | - | - | 65,593 | 81,545 | 85,204 |

| Serbs | 25,177 | 27,933 | 25,076 | 21,834 | 19,064 | 17,599 | 16,234 | 14,142 |

| Muslims | - | 23,250 | 37,140 | 49,769 | 64,251 | 1,599 | - | 1,851 |

| Roma | - | 37 | 210 | 444 | 334 | 69 | 566 | 486 |

| Gorani | - | - | - | - | - | 15 | 246 | 255 |

| Albanians | 144 | 126 | 307 | 233 | 209 | 129 | 202 | 200 |

| Montenegrins | 174 | 543 | 359 | 295 | 232 | 109 | 44 | 34 |

| Yugoslavs | 13,564 | 1,261 | 183 | 931 | 700 | 136 | 67 | 72 |

| Turks | 11,009 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Others | 263 | 5,627 | 1,057 | 494 | 459 | 747 | 4,476 | 161 |

| Total | 50,331 | 58,777 | 64,326 | 74,000 | 85,249 | 85,996 | 100,410 | 106,720 |

Ethnic composition of the urban area of the city:

| Ethnic group | Population 1948[35] |

Population 1953[27] |

Population 1981[30] |

Population 1991[31] |

Population 2002[32] |

Population 2011[33] |

Population

2022[36] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bosniaks/Muslims | 1,085 | - | 32,798 | 43,774 | 47,243 | 58,252 | 60,684 |

| Serbs | 10,678 | 3,466 | 6,689 | 6,698 | 6,724 | 6,576 | 6,067 |

| Gorani | - | - | - | - | - | 240 | 235 |

| Albanians | - | 134 | 208 | 172 | 120 | 162 | 158 |

| Yugoslavs | - | 5,944 | 848 | 570 | 105 | 64 | 68 |

| Turks | - | 4,280 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Montenegrins | - | 145 | 246 | 190 | 93 | 39 | 34 |

| Others | 229 | 135 | 310 | 345 | 1,541 | 3,304 | 4,217 |

| Total | 11,992 | 14,104 | 41,099 | 51,749 | 54,604 | 68,749 | 71,462 |

Settlements

Aside from the urban area of Novi Pazar (54,604), the city administrative area includes the following settlements, with population from the 2002 census:

- Aluloviće (362)

- Bajevica (563)

- Banja (466)

- Bare (36)

- Batnjik (58)

- Bekova (116)

- Bele Vode (872)

- Boturovina (218)

- Brđani (195)

- Brestovo (5)

- Čašić Dolac (76)

- Cokoviće (20)

- Deževa (238)

- Dojinoviće (120)

- Dolac (87)

- Doljani (89)

- Dragočevo (112)

- Dramiće (80)

- Golice (64)

- Gornja Tušimlja (33)

- Goševo (50)

- Gračane (28)

- Građanoviće (19)

- Grubetiće (259)

- Hotkovo (193)

- Ivanča (813)

- Izbice (1,949)

- Jablanica (27)

- Janča (332)

- Javor (18)

- Jova (21)

- Kašalj (35)

- Koprivnica (12)

- Kosuriće (125)

- Kovačevo (243)

- Kožlje (618)

- Kruševo (486)

- Kuzmičevo (133)

- Leča (319)

- Lopužnje (70)

- Lukare (489)

- Lukarsko Goševo (850)

- Lukocrevo (186)

- Miščiće (231)

- Muhovo (545)

- Mur (3,407)

- Negotinac (26)

- Odojeviće (50)

- Oholje (179)

- Okose (36)

- Osaonica (284)

- Osoje (966)

- Paralovo (982)

- Pasji Potok (42)

- Pavlje (178)

- Pilareta (26)

- Pobrđe (2,176)

- Polokce (117)

- Pope (83)

- Postenje (3,471)

- Požega (523)

- Požežina (251)

- Prćenova (159)

- Pusta Tušimlja (53)

- Pustovlah (28)

- Radaljica (152)

- Rajčinoviće (537)

- Rajčinovićka Trnava (208)

- Rajetiće (63)

- Rajkoviće (29)

- Rakovac (21)

- Rast (51)

- Šaronje (398)

- Šavci (247)

- Sebečevo (897)

- Sitniče (778)

- Skukovo (23)

- Slatina (297)

- Smilov Laz (8)

- Srednja Tušimlja (40)

- Štitare (77)

- Stradovo (19)

- Sudsko Selo (87)

- Tenkovo (89)

- Trnava (694)

- Tunovo (128)

- Varevo (501)

- Vever (18)

- Vidovo (90)

- Vitkoviće (30)

- Vojkoviće (36)

- Vojniće (115)

- Vranovina (329)

- Vučiniće (245)

- Vučja Lokva (15)

- Zabrđe (49)

- Zlatare (12)

- Žunjeviće (211)

Politics

Novi Pazar is governed by a city assembly composed of 47 councillors, a mayor and vice-mayor. After the last legislative election held in 2020, the local assembly is composed of the following groups:[37]

- SDP - European Novi Pazar - Rasim Ljajić (21)

- SPP - Muamer Zukorlić (11)

- SDA - Party of Democratic Action of Sandžak (9)

- Aleksandar Vučić - SNS, SPS, SRS (6)

Economy

Lying on crossroads between numerous old and new states, Novi Pazar has always been a strong trade center. Along with the trade, the city developed manufacturing tradition. During the 20th century, it became a center of textile industry.

Paradoxically, during the turbulent 1990s and, Novi Pazar prospered, even during the UN sanctions, boosted by the strong private initiative in textile industry. Jeans of Novi Pazar, first of forged trademarks, and later on its own labels, became famous throughout the region. However, during the relative economic prosperity in Serbia of the 2000s, the Novi Pazar economy collapsed, with demise of large textile combines in mismanaged privatization, and incoming competition from the import.

As of 2023, Novi Pazar was having around 23,000 unemployed inhabitants, making it one of the cities in Serbia with the highest unemployment rate (around 50%).[38] Some of the main reasons for this was unstable political situation during the 1990s and 2000s, and underdeveloped infrastructure (with no international airports, motorways and railways nearby).[38]

- Economic figures

The following table gives a preview of total number of registered people employed in legal entities per their core activity (as of 2022):[39]

| Activity | Total |

|---|---|

| Agriculture, forestry and fishing | 72 |

| Mining and quarrying | 13 |

| Manufacturing | 3,173 |

| Electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning supply | 144 |

| Water supply; sewerage, waste management and remediation activities | 497 |

| Construction | 1,957 |

| Wholesale and retail trade, repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles | 3,902 |

| Transportation and storage | 1,717 |

| Accommodation and food services | 924 |

| Information and communication | 198 |

| Financial and insurance activities | 216 |

| Real estate activities | 8 |

| Professional, scientific and technical activities | 634 |

| Administrative and support service activities | 186 |

| Public administration and defense; compulsory social security | 1,404 |

| Education | 2,741 |

| Human health and social work activities | 1,806 |

| Arts, entertainment and recreation | 276 |

| Other service activities | 633 |

| Individual agricultural workers | 441 |

| Total | 20,944 |

Society and culture

Monuments

The old Serbian Orthodox monastery of Sopoćani, the foundation of St King Uroš I, built in the second half of the 13th century and located west of Novi Pazar, is a World Heritage Site since 1979 accompanying with Stari Ras (Old Ras), a medieval capital of the Serbian great župan Stefan Nemanja.[40][41][42]

The city also houses the oldest intact church in Serbia and one of the oldest ones in the region which dates from the 9th-century, the Church of St Peter. The church's walls were defaced with graffiti on 6 April 2008. The police have not officially concluded why the incident occurred.[43]

On a hilltop overlooking Novi Pazar is the 12th century monastery of Đurđevi stupovi, long left in ruin, but recently restored and with a monastic community using it, with plate glass to keep out the weather and preserve the fine frescos. The main mosque of the city, the Altun-Alem Mosque, was built in the first half of the 16th century by architect Abdul Gani.[44][45]

There are various other historic Ottoman buildings, such as the 17th-century Amir-agin Han, a 15th-century Hammam, and the 15th-century Turkish fortress (all gone but the walls, the site of which is now a walled park in the city centre).[46][47]

Education

Novi Pazar is home to two universities, the International University of Novi Pazar and the State University of Novi Pazar.

Sport

The city's football club FK Novi Pazar was founded in 1928, under the name "FK Sandžak", which later changed to "FK Deževa". The club has played under its current name since 1962, when Deževa and another local football club, FK Ras, unified under this name. The club was a SFRJ amateur champion, and a member of the Yugoslav Second League. FK Novi Pazar qualified for a promotional play-off twice, but lost both times (to FK Sutjeska Nikšić in 1994, and to FK Sloboda Užice in 1995). FK Novi Pazar finally promoted to Serbian SuperLiga in 2011–12 season. FK Novi Pazar is the oldest second-league team in Serbia. Football is still an extremely popular sport in Novi Pazar and the city stadium is always full.

Volleyball clubs in the city are OK Novi Pazar (first league) and OK Koteks.

The Handball club is in the second league and used to have the name "Ras" but it was changed to RK Novi Pazar in 2004.

The Basketball club of the city is OKK Novi Pazar.

Famous athletes from the city include Turkish basketball national team player Mirsad Jahović Türkcan, former football player of Besiktas Sead Halilagić, handball-player Mirsad Terzić (who represents Bosnia and Herzegovina) and young football players Adem Ljajić, Ediz Bahtiyaroğlu, Armin Đerlek.

International cooperation

List of Novi Pazar's sister and twin cities:[48]

Shusha, Azerbaijan

Shusha, Azerbaijan Bayrampaşa, Turkey

Bayrampaşa, Turkey İnegöl, Turkey

İnegöl, Turkey Jagodina, Serbia

Jagodina, Serbia Karatay, Turkey

Karatay, Turkey Kocaeli Province, Turkey

Kocaeli Province, Turkey Novi Pazar, Bulgaria

Novi Pazar, Bulgaria Pendik, Turkey

Pendik, Turkey Vranje, Serbia

Vranje, Serbia Yalova, Turkey

Yalova, Turkey

Other friendships and cooperations, protocols, memorandums:[48][49]

Goražde, Bosnia and Herzegovina

Goražde, Bosnia and Herzegovina Ilidža, Bosnia and Herzegovina

Ilidža, Bosnia and Herzegovina Podgorica, Montenegro

Podgorica, Montenegro Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina

Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina Sombor, Serbia

Sombor, Serbia Damietta, Egypt

Damietta, Egypt

Gallery

- Novi Pazar city center

- Novi Pazar city center

- Novi Pazar city center

- Novi Pazar Mosque in the neighborhood

- Archeological artifacts, Museum of Ras

- Serbian household from the 19th and early 20th century, Museum of Ras

Notable residents

- Tahir Efendi Jakova (1770–1850), Albanian poet

- Aćif Hadžiahmetović (1887–1945), politician, mayor of Novi Pazar during Second World War

- Milunka Savić (1888–1973), the most-decorated female combatant in the entire history of warfare

- Abdulah Gegić (1924–2008), former Partizan Belgrade football coach

- Ejup Ganić (b. 1946), engineer and politician

- Laza Ristovski (1956–2007), Yugoslav keyboardist, member of Smak and Bijelo Dugme

- Rasim Ljajić (b. 1964), politician

- Muamer Zukorlić (1970–2021), politician and Islamic theologian

- Mirsad Jahović Türkcan (b. 1976), Turkish basketball player

- Emina Jahović (b. 1982), pop singer

- Miljan Mutavdžić (b. 1986), football player

- Adem Ljajić (b. 1991), football player

- Amela Terzić (b. 1993), runner

- Erhan Mašović (b. 1998), football player

- Hamad Medjedovic (b. 2003), tennis player

References

- ^ "Municipalities of Serbia, 2006". Statistical Office of Serbia. Retrieved 2010-11-28.

- ^ "2022 Census of Population, Households and Dwellings: Ethnicity (data by municipalities and cities)" (PDF). Statistical Office of Republic Of Serbia, Belgrade. April 2023. ISBN 978-86-6161-228-2. Retrieved 2023-04-30.

- ^ a b "2022 Census of Population, Households and Dwellings" (PDF). Retrieved 2023-12-07.

- ^ Ahrens, Geert-Hinrich (6 March 2007). Diplomacy on the Edge: Containment of Ethnic Conflict and the Minorities Working Group of the Conferences on Yugoslavia. Woodrow Wilson Center Press. pp. 223–. ISBN 9780801885570. Retrieved 2 January 2013.

- ^ Novosel, Piše: S. (14 April 2019). "Reljina gradina postala spomenik kulture". Dnevni list Danas (in Serbian). Retrieved 2020-10-25.

- ^ "bazaar". Retrieved 2007-02-17.

- ^ Voisinages fragiles : les relations interconfessionnelles dans le Sud-Est européen et la Méditerranée orientale, 1854-1923 : contraintes locales et enjeux internationaux. Sía. Anagnostopoúlou, Nikolaos Andriṓtīs, Eva Anne Frantz, Elena Astafieva, Jérôme Bocquet, Patrick Cabanel, Nathalie Clayer, Giuseppe M.. Croce, Nadâ. Danova, Kōstas Kōstis, Andreas Lyberatos, Milena Bogomilova Methodieva, Laura Pettinaroli, Claude Prudhomme, Inès. Sabotic, Dominique Trimbur, Chantal Verdeil, Anastassios Anastassiadis. Athènes. 2021. p. 57. ISBN 978-2-86958-531-7. OCLC 1259601396.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Climate: Novi Pazar, Serbia". Climate-Data.org. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- ^ Više autora, Novi Pazar i okolina, Beograd 1969.[page needed]

- ^ Norris, H. T. (1993). Islam in the Balkans: Religion and Society Between Europe and the Arab World. Hurst. pp. 49–. ISBN 9781850651673. Retrieved 2 January 2013.

Novi Pazar, on the border of Kosovo, was founded by Isa Beg, a governor of Bosnia

- ^ Yürür, Pinar; Özkan, Arda, eds. (2020). Conflict Areas in the Balkans. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 185. ISBN 9781498599207.

- ^ Holger H., Richard F. Hamilton (24 February 2003). The Origins of World War I. Cambridge University Press. p. 103. ISBN 9781107393868.

- ^ Skendi, Stavro (2015). The Albanian National Awakening. Cornell University Press. p. 201. ISBN 978-1-4008-4776-1.

- ^ HALL, RICHARD C. (2002). The Balkan Wars 1912-1913: Prelude to the First World War Warfare and History. Routledge. ISBN 9781134583621.

- ^ N., M. (3 November 2016). "Zukorlić: Sa stokom reforme nemoguće". novosti.rs (in Serbian). Retrieved 17 February 2017.

- ^ "Zoran Đinđić dobija ulicu u Novom Pazaru". blic.rs (in Serbian). Tanjug. 12 March 2015. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

- ^ "Comparative overview of the number of population in 1948, 1953, 1961, 1971, 1981, 1991, 2002, 2011. and 2022". Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia.

- ^ "STANOVNIŠTVO". novipazar.rs (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 19 June 2014. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- ^ "Number and the floor space of housing units" (PDF). stat.gov.rs (in Serbian). Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- ^ a b c "Religion, Mother tongue, and Ethnicity" (PDF). stat.gov.rs (in Serbian). Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- ^ "Educational attainment, literacy and computer literacy" (PDF). stat.gov.rs (in Serbian). Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- ^ Hall, Richard C. (2002-01-04). The Balkan Wars 1912-1913: Prelude to the First World War. Taylor & Francis. p. 5. ISBN 9780203138052. Retrieved 2 January 2013.

The Sandjak of Novi Pazar was a finger of the Ottoman province of Kosovo, which separated Montenegro from Serbia. The Sandjak of Novi Pazar had a mixed population of Albanians, Serbs, and Slavic-speaking Muslims.

- ^ Mihaljević, Marina. The Jewish Heritage of Novi Pazar: A Case of Decaying Memory (Journal of the North American Society for Serbian Studies, January 2013), p. 103.

- ^ Mušović, Ejup (1979), Etnički procesi i ethnička struktura stanovništva Novog Pazara, Etnografski Institut, 1979, p.48

- ^ "Comparative Overview of the number of population in 1948, 1953, 1961, 1971, 1981, 1991, 2002 and 2011" (PDF). stat.gov.rs. Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. 2012. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- ^ Comparative survey of population 1948, 1953, 1961, 1971, 1981, 1991 and 2002 : data by localities (in Serbian). Belgrade: Republički zavod za statistiku. 2004. ISBN 86-84433-14-9.

- ^ a b "UKUPNO STANOVNIŠTVO PO NARODNOSTI (1953)" (PDF). stat.gov.rs. Republički zavod za statistiku. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ "Knjiga III: Nacionalni sastav stanovništva FNR Jugoslavije (1961)" (PDF). stat.gov.rs (in Serbian). Republički zavod za statistiku. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ "Knjiga III: Nacionalni sastav stanovništva FNR Jugoslavije (1971)" (PDF). stat.gov.rs (in Serbian). Republički zavod za statistiku. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ a b "Nacionalni sastav stanovništva SFR Jugoslavije (1981)" (PDF). stat.gov.rs. Republički zavod za statistiku. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ a b "STANOVNIŠTVO PREMA NACIONALNOJ PRIPADNOSTI (1991)" (PDF). stat.gov.rs. Republički zavod za statistiku. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ a b "Popis stanovništva, domaćinstava i stanova u 2002" (PDF). stat.gov.rs (in Serbian). Republički zavod za statistiku. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ a b "Попис становништва, домаћинстава и станова 2011. у Републици Србији" (PDF). stat.gov.rs. Republički zavod za statistiku. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ "Ethnicity: Data by municipalities and cities" (PDF). publikacije.stat.gov.rs. Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. p. 80.

- ^ "UKUPNO STANOVNIŠTVO PO NARODNOSTI (1948)" (PDF). stat.gov.rs. Republički zavod za statistiku. Retrieved 25 December 2016.

- ^ "Ethnicity: Data by municipalities and cities" (PDF). publikacije.stat.gov.rs. Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia.

- ^ "Skupština grada". Novipazar.rs. Archived from the original on 2012-09-04. Retrieved 2014-08-08.

- ^ a b Novosel, S. (7 May 2024). "U Novom Pazaru približan broj zaposlenih i nezaposlenih". danas.rs (in Serbian). Retrieved 21 September 2024.

- ^ "MUNICIPALITIES AND REGIONS OF THE REPUBLIC OF SERBIA, 2023" (PDF). stat.gov.rs. Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. Retrieved 20 September 2024.

- ^ Stari Ras and Sopoćani, whc.unesco.org

- ^ By Their Fruit you will recognize them - Christianization of Serbia in Middle Ages, Perica Speher, 2010.

- ^ Upadhya, Om (1994). The art of Ajanta and Sopoćani: A comparative study: An enquiry in prāṇa aesthetics. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. p. 25. ISBN 81-208-0990-4.

- ^ "Oldest Orthodox church in Balkans (Serbian Orthodox Church) defaced". Spc.rs. Archived from the original on 25 September 2020. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ^ „Sve o Altun-alem džamiji”. Ras.rs. 30. 1. 2011. Архивирано из оригинала на датум 16. 01. 2016. Приступљено 21. 8. 2015.

- ^ "Altun-alem Mosque, Novi Pazar". www.serbia.travel. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved March 24, 2016.

- ^ Амир-агин хан, spomenicikulture

- ^ Стари амам — Споменици културе у Србији, spomenicikulture

- ^ a b "Grad Novi Pazar u pobratimstvu sa Jagodinom i Vranjem, sa Sarajevom samo odnosi saradnje" (website). sandzakpress. 6 December 2017. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- ^ https://www.instagram.com/p/C9cmQ4uifjp (Official instagram post of the mayor referring to the new relationship with Damietta)